Introduction

Once, over the course of five weeks, I graded – and commented upon – just over four hundred student papers.

It was mind-blistering work. I was asked by a colleague if this experience passed a cost-benefit analysis. Many of these papers were drafts (or important student reflections) and thus demanded more care; students would be building their ideas off my comments.

In the end, their final papers – which received minimal comments from me – were mostly enjoyable to read. In my assessment, my work had paid off. Ultimately, efficient and effective grading requires the front-loading of instructor effort as well as strategic off-loading to students.

After several years, I like to think I’ve become better at offering constructive criticism of student writing and becoming more effective at helping students write critically. Below, I offer some of the slides I presented on this topic for our university’s Instructional Development program for TAs and add some additional commentary.

The workshop was divided into three discussion themes: Before Grading, While Grading, and After Grading. (The slides below carry most of the information.)

Setting the Scene

Our workshop was fairly small so I started by surveying our group’s attitudes towards elements of the writing process. Using Mentimeter, the first question asked the attendees to rate their opinions of the importance of drafting, peer-review, and creating rubrics:

Question 1: On scale of 1-5, how necessary would you evaluate each action/activity: student rough drafts, creating grading rubric, student peer-review.

The numbers above represent the averages of the individual responses (“5” being the most “necessary”). Of those, creating grading rubrics was deemed the most important among our group. Happily, this aligned with the work-shopping component of my presentation. Drafting and peer review require some “experience” (ahem, failures) on the teacher’s part to get it “right.” Nevertheless, I consider all three to be closely related, I’ll return to this below.

The second question asked the participants to do a cost-benefit analysis of creating rubrics, setting up peer-review, and giving ample commentary:

Question 2: What is your relative impact-effort evaluation of each action/activity: student rough drafts, creating grading rubric, student peer-review.

Not surprisingly, providing feedback was the most time-intensive, but it’s value was on par with crafting a good rubric. As I noted above, there’s an inverse value to feedback as the semester progresses. It’s most valuable early in the term, when students can adjust their habits and styles (and build their ideas); there is minimal value on maximal feedback at the end of the term.

The final question was more straightforward: how long does it take to read, comment significantly, and grade a five-page paper?

Question 3: How long does it take for you to comment on a 5-page student paper?

I asked this question to get a sense of how others operate – we instructors often don’t talk about these types of things with each other. At the very least, I think its important to have an internal estimate of our grading times so we do not go overboard with commenting.

Personally, I have not been able to break the 15 minute barrier for five-page papers. I average about 18 minutes.

As such, I set a timer for each paper I read at 20 minutes and always try to “beat” it. (Perhaps I can call this a variant of the Pomodoro Technique.)

Before Grading

Before diving into my presentation formally, my favorite suggestions for managing paper load comes from Shelley Reid’s insightful thoughts posted in her “Shelley’s Quick Guides for Writing Teachers.” Many of Reid’s principles are sprinkled into my presentation here.

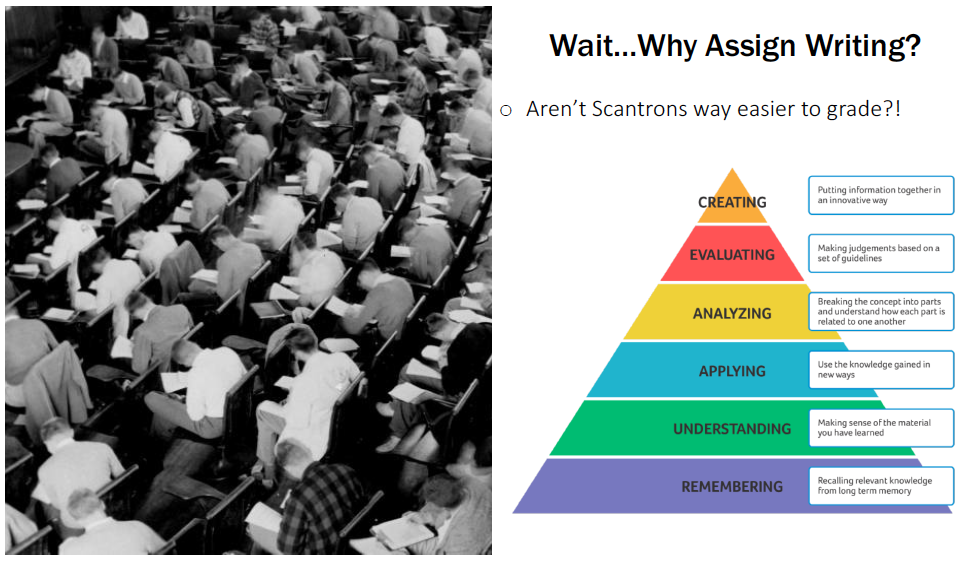

I start by asking why instructors should assign papers at all. Its important to keep in mind the value of writing for recruiting “higher orders” of thinking: applying, evaluating, creating, etc. This kind of thinking is impossible to access, for example, through multiple choice exams.

It’s also important to think about which orders of thinking your writing prompt(s) address; some writing prompts may only ask students to list elements of a concept or theory. This remains in the lower order of “remembering” (see Bloom’s Taxonomy below).

It is, of course, harder to evaluate, comment upon, and grade higher orders of thinking.

Slide 1

Instructors can do several things to off-load more of the conceptual “heavy lifting” to students – and thus have them build more of the conceptual “muscle.”

Having students draft is an important step in the writing process because it allows them to develop (and become more invested in) their ideas. If you pair this with a structured peer-review, there is actually minimal work for the instructor. Of course, peer-review requires structure and guidance. Students need to practice and learn the skill of critical reading and constructive criticism.

This is important to keep in mind if you are the only one providing commentary on student writing, you are doing some of the “muscle-building work” students could – should? – be doing themselves.

I offer the next few slides with minimal comment, but feel free to review the text in each one.

Slide 2

Slide 3

Slide 4

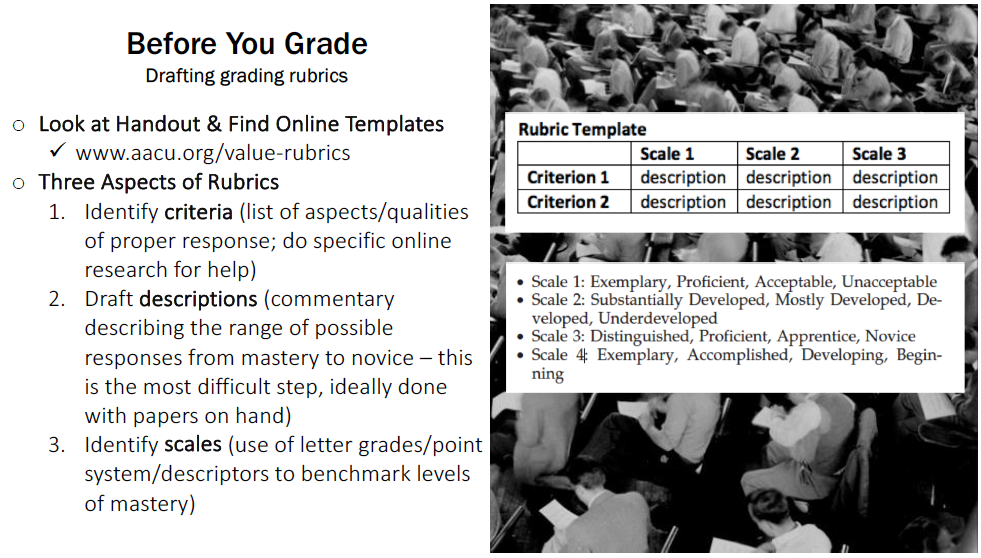

After reviewing the basic components of grading rubrics (criteria, description, scale), we spent time looking for relevant rubric templates online – there is no need to re-invent the wheel! There are many resources available that can inspire your rubric divisions. I provided the following handout for consultation: Creating Grading Rubrics Handout.

After discussing some strategies “before you grade,” I switch to pragmatic suggestions “while you grade.”

While Grading

Slide 5

Slide 6

Slide 7

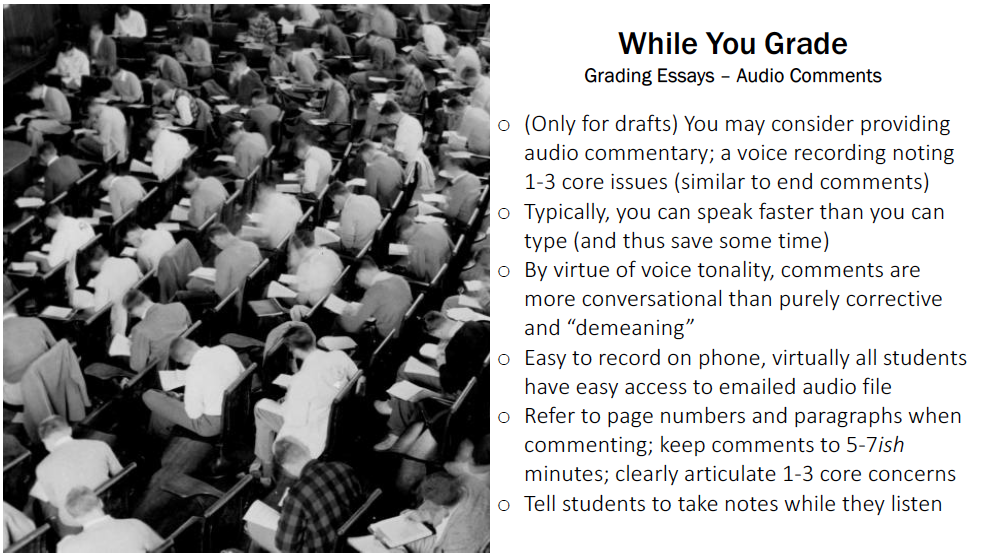

I have long been a covert to audio commentary and have suggested it to many of my colleagues. If you have the space (the one limiting factor is you need a generally quiet location), it’s worth a try. Finally, I ended with a few thoughts on “after you grade.”

After Grading

Slide 8

Slide 9

Slide 10

Edit: This post below addresses several similar issues, but adds other interesting insights: https://movingwriters.org/2018/07/16/sy-2017-2018-top-ten-in-pursuit-of-meaningful-feedback/

Workshop Posts

Very cool! Insightful.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed this post. I teach first-year comp. too, and I struggle with grading not eating up the majority of my life. I do the timer too, and I’ve found that extensive rubrics, like you said, are extremely helpful in speeding me up. Doing the shorthand helps too, and I give students a list of what the shorthand symbols mean at the beginning of the semester when I had out my syllabus. One thing that I’ve found to help speed me up too is that I skip reading the quotes that my students use. I’ll see how they introduce and cite the quote, but what I’m really interested in is their analysis of the information in the quote. If their analysis seems a little wonky (or is there is little or no analysis), then I’ll go back to read the quote and figure out what went wrong, but other than that, I try to skip the quotes. I really like how you turned something like grading into quantitative data that you can actually see.

LikeLike