During the long period of British rule in Burma (modern Myanmar), the Imperial Post Office of India, established in 1837, oversaw all mail delivery across British India, which included a circuit in eastern-most Burma. Postcards were introduced through the British postal department in 1879 and were first marketed at the inexpensive rate of a quarter-anna. That same year, a popular Indian newspaper proclaimed, “Postal cards are now a rage all over India.”[1]

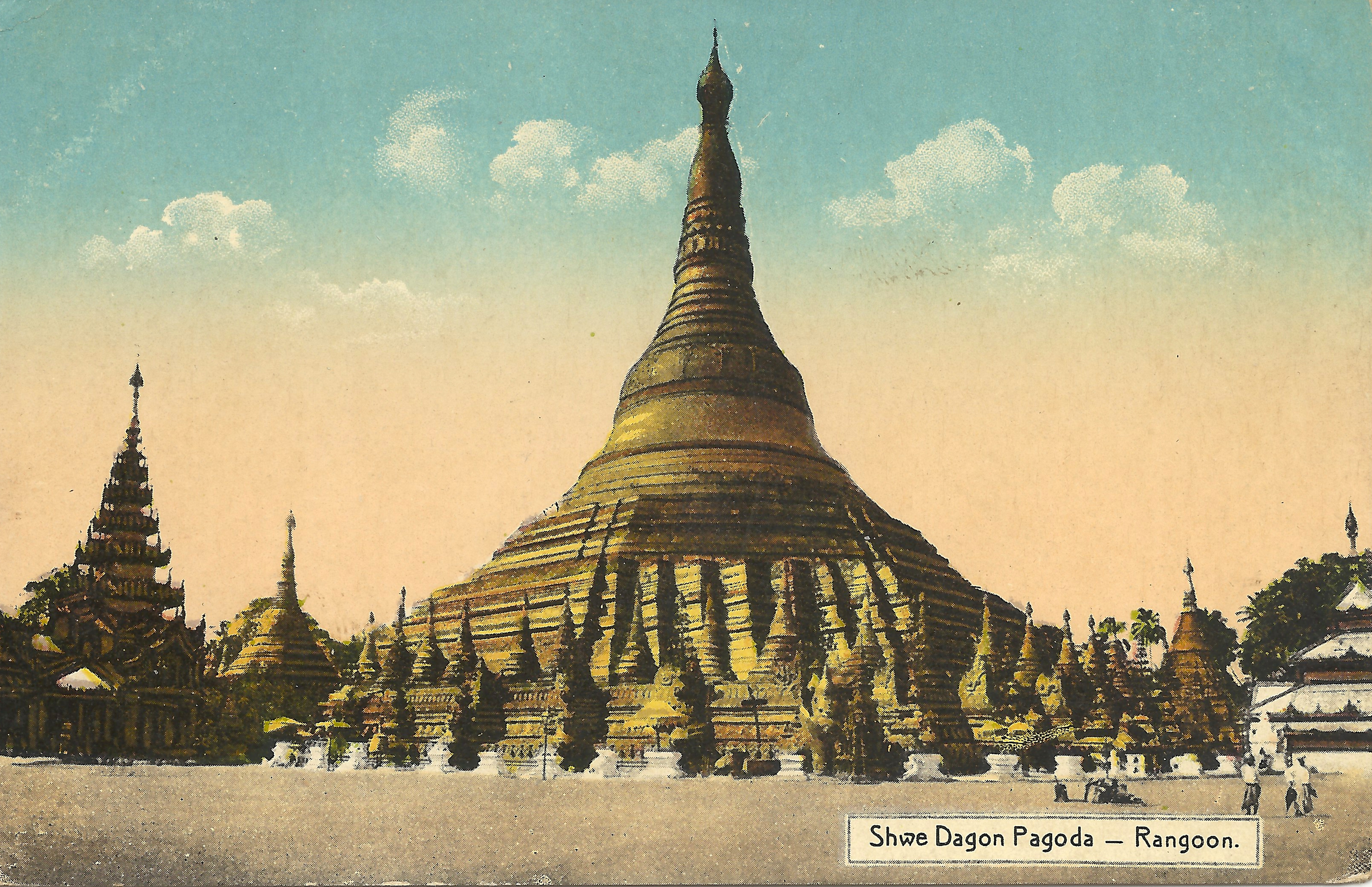

The immediate popularity of the mail system, and postcards in particular, was not the case in Burma, however. Few Burmese elected to use the colonial mail system (unlike in India, Burma had no native mail system previous to British occupation) and postal employees conversant in Burmese were difficult to recruit. By the 1890s, postcards were still a rarity in both Lower and Upper Burma. And while more then fourteen million letters and postcards were sent across the Burmese province in 1900, more than three quarters were written by non-Burmese.[2] Nevertheless, a viable commercial postcard market grew in the first decade of the twentieth century, centered in the provincial capital of Rangoon (modern Yangon). Most of the early Burmese postcard publishers operated professional photography studios and thus many postcard images can also be found in commercial tourist albums now in personal and private collections around the world. This included the work of Felice Beato, Philip Klier, D.A. Ahuja, and Frederick Albert Edward Skeen and Harry Walker Watts. A sizable collection of Burmese postcards can be found in the Pitt Rivers Museum archive at the University of Oxford, donated in 1986 by the Burma-born artist Noel F. Singer, and the wonderfully digitized collection of Sharman Minus.

D. A. Ahuja

The firm D.A. Ahuja & Co. was the largest publisher of postcards in colonial Burma and continued operation through the early 1960s. Very little is known about the personal life of the proprietor, D.A. Ahuja (fl. early 20th c.), but he claims to have established his business in Rangoon in 1885. It is likely he immigrated from India, along with thousands of other Indians during the colonial period, but his family’s precise origins remain debated, with both Punjab and Shikarpur (in modern Pakistan) as suggestions. The earliest firm documentation comes in 1900, when he announced the change of his company name from Kundandass & Co. to his own personal name, located at 87 Dalhousie Street in Rangoon. The following year Ahuja published a photography manual in Burmese and in English translation, with the latter entitles Photography in Burmese for Amateurs. In a 1917 advertisement, pictorial postcards remained “a specialty” for Ahuja, but his business had expanded beyond photography and involved exporting a wide variety of Burmese goods.[3]

Ahuja produced some of the most distinctive and vibrant color postcards in South Asia. As is noted on the reverse of his cards, they were printed in Germany, then the commercial center of postcard printing. German printers used as lithographic-halftone hybrid process, first applying layers of color using a lithographic substrate and then applying a black halftone screen. Only the final key plate (i.e. black ink plate) carried the fine detail of the photograph. Several of Ahuja’s images were taken from his competitors, including Philip Klier and Watts & Skeen. While Ahuja apparently bought out the photographic stock of Watts & Skeen, Klier filed a lawsuit against Ahuja for copyright infringement in 1907. Klier won the claim, but it appears Ahuja paid for the rights to reproduce Klier’s photographs since he continued to print them years after the lawsuit.

I still remain uncertain when the colonial British post office allowed divided back postcards. This began in England in 1902, but thus far I have not confirmed if this was the case for the Post Office of India. Postcards were first introduced nine years later in British India, thus I assume there might be a lag in changes in Indian postal code.

Undivided Back

Divided Back

Philip Klier

Philip Adolphe Klier (1845-1911) first arrived in Moulmein, Lower Burma, in 1870 and established business that offered a range of services, one of them being a photography studio. By the late 1870s he created a large portfolio of photographs and moved to a new location in Rangoon, the bustling capital of British Burma. Klier’s business continued after his death for about another decade.

Klier produced large format albumen prints of various locations around Burma, focusing on the major cities of Moulmein, Rangoon, and Mandalay. His studio photographs would be inscribed with the name of the locaiton and a stock number while later photos from the late 1880s or early 1890s would also include his name. A large digitized collection of Klier’s work is housed at the National Gallery of Australia. It is difficult to ascertain when Klier started publishing postcards from his photography stock, but it was certainly sometime during the 1890s, perhaps as early as 1890. Noel Singer has suggested the well known German printer, Verlag v. Albert Aust, in Hamburg partnered with Klier to produce a series, Birma Series Asien.[4] The earliest issues (at least, imprinted with Klier’s name) were collages, typically of two or three monochromatic photographs with significant blank incorporated around the images for correspondence. Eventually, this style gave way to single photo cards and then colored cards.

The analysis below is preliminary – there appear to be a wide variety of variants in both the obverse and reverse design.

Undivided Back

Divided Back

Notes

[1] Clarke 1921: 8.

[2] Frost 2016: 1059.

[3] Berchiolly 2018: 113. I am indebted to Berchiolly’s work for the life of Ahuja and Klier.

[4] Noted in Berchiolly 2018: 98.

References

- Berchiolly, Carmin. 2018. “Capturing Burma: Reactivating Colonial Photographic Images through the British Raj’s Gaze,” MA Thesis, Northern Illinois University.

- Birk, Lukas and Berchiolly, Carmín. Reproduced: Rethinking P.A. Klier and D.A. Ahuja. Vienna: Fraglich Publishing.

- Clarke, Geoffrey. 1921. The Post Office of India and its Story. London.

- Davis, G., and Martin, D. 1971. Burma Postal History. London.

- Falconer, John. 2014. “Cameras at the Golden Foot: Nineteenth-century Photography in Burma,” in 7 Days in Myanmar: A Portrait of Burma by 30 Great Photographers, by John Falconer, Denis Gray, Thaw Kaung, Patrick Winn, Nicholas Grossman, and Myint-U Thant. Singapore: Didier Millet, pp. 27-29.

- Frost, Mark. R. 2016. “Pandora’s Post Box: Empire and Information in India, 1854–1914,” English Historical Review, Vol. 131, No. 552, pp 1043-73.

- Imamura, Jackie. “Early Burma Photographs at the American Baptist Historical Society,” Archives, Vol. 4, No. 1. [here]

- Khan, Omar. 2018. Paper Jewels: Postcards form the Raj. Mapin Publishing Pvt. Limited. [also see website below]

- Sadan, Mandy . 2014. “The Historical Visual Economy of Photography in Burma,” Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia, Vol. 170, pp. 281-312.

- Singer, Noel F. 1993. Burmah: A Photographic Journey, 1855-1925. Gartmore, Stirling: Paul Strachan Kiscadale.

- Singer, Noel F. 1999. “Philipp Klier: A German Photographer in Burma,” Arts of Asia, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 106-13.

Online Resources

- Indian Philately Digest: Postal history [http://www.indianphilately.net/plitph.html]

- Myanmar Photo Archive [http://www.myanmarphotoarchive.org/]

- New York Public Library, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection/Pacific Pursuits: Postcards – Myanmar A-Z and Myanar Life [e.g. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/pacific-pursuits-postcards#/?tab=navigation&roots=29:7bb3ab70-c5d2-012f-c7f8-58d385a7bc34]

- Paper Jewels: Postcards from the Raj [https://www.paperjewels.org/]

- Pitt Rivers Museum [current online collection does not include Burmese postcards, but a selection can be found here and here]