[This is a online version of my Archive exhibit at the UCSB Religious Studies Department. Many thanks to Will Chavez for his enthusiastic support and assistance.]

What do you think the Buddha looked like?

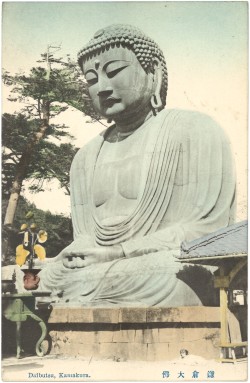

My research has been guided by this deceptively complex question. As Americans were first introduced to Buddhism on a mass level in the latter half of the nineteenth century, I became interested in how they also developed a “visual literacy” of Buddhist images. Before the happy Laughing Buddha was popular, the Great Buddha of Kamakura was the most prominent visual icon. This Great Buddha, or in Japanese, “Daibutsu,” was constructed in 1252. Here’s a look of how this statue made its way into the American imagination.

The Albumen Print and Yokohama Shashin

The popularity of the Kamakura Daibutsu in America was accidental. When Japan re-opened its borders to foreigners in 1859, the port of Yokohama – a short day’s ride from Kamakura – was selected as one of the treaty ports were foreigners could legally reside. The close proximity of Kamakura Daibutsu to this bustling port city was a significant factor in its blossoming popularity.

In addition, two other factors played a role in the recognizability of the Kamakura Daibutsu: the development of the international tourism industry and the invention of the camera. Globetrotting tourists who hoped to preserve their picturesque travels in souvenir photographs unwittingly helped promote a visual identity of an exotic Japan back home in America, with geisha, rickshaws, and Buddhist “idols,” such as the Kamakura Daibutsu.

Because of the sheer number of wealthy tourists in Yokohama, professional photography studios started to open their doors for business. These studios, operated at first by foreign residents, sold souvenir albums to fit the needs of their eager clientele. These souvenir photos were called Yokohama shashin, or “Yokohama photographs,” due to the high concentration of studios in this port city.

Adolfo Farsari (1841-1898), an Italian adventurer, eventually settled in Yokohama in the 1870s. Farsari entered a fiercely competitive photography industry when he bought out an established photography studio to open his own firm, A. Farsari & Co. Like his competitors, he sold photographs and pre-made albums to wealthy “globetrotters” who sought to return home with photographs of famous sites.

The first commercially viable photographic process produced what are known as albumen prints. They used albumen found in egg whites to bind the photosensitive chemicals to the paper.

After the monochromatic print was processed, artists would hand apply watercolor washes to provide vibrant color. Often these artists were Japanese, some who may have been trained in traditional Japanese woodblock printing.

Picture Postcards and the Collotype Process

Although photography had been in existence for over half a century, some claim that the first truly commodified form of the photograph was the picture postcard. Small and inexpensive, the postcard was a convenient souvenir that could easily be sent around the world for the appreciation and amusement of someone else.

The Japanese postal delivery service began in 1870, but it was not until 1900 that new postal regulations allowed for private companies to print their own postcards. In Japan, the postcard soon rivaled the traditional woodblock print as the favored medium to present contemporary Japanese images.

Early postcard images were commonly recycled photographs from old souvenir photography studios. In 1905, spurred by the international interest in photographing the Russo-Japanese War, a picture postcard boom hit Japan, breathing life into a new industry and collecting hobby. Still catering to a thriving tourism industry, the private postcard publishers reshot the same generic imagery that sold well as albumen prints, including the Kamakura Daibutsu.

One of the most prolific postcard publishers of the period was the Ueda Photographic Prints Corporation, founded by Ueda Yoshizō上田義三 in the port of Yokohama around 1905. Because printing photos was exceptionally expensive and time consuming, new mechanical photographic reproduction processes were soon invented. The development of a new printing technique, called the collotype, allowed for photomechanical printing – and the creation of inexpensive postcards – on a massive scale.

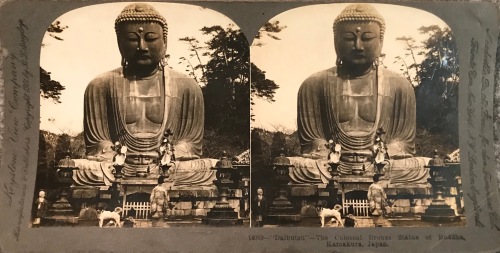

Stereophotography and Stereoviews

Perhaps one of the most curious forms of early photography involved a technique for making stereoscopic images. By placing a pair of slightly different images – taken by two cameras separated by about the distance between a person’s eyes – and viewing them through a stereoscope, they would merge and create an illusion of depth, thus mimicking three dimensional viewing. An early form of virtual reality, stereocards, or stereoviews, became wildly popular by the end of the nineteenth century.

Although some stereoviews were sold in Japan, most stereoviews were sold directly to Americans in department stores, through mail-order catalogues, and by savvy door-to-door salesmen. A surviving manual for salesman instructs them in the “hard sell,” scripting a sales pitch to say: “You see, nearly everyone is getting a ‘scope and views, and really, so should you. One like this will last you all your days.”

Mass produced Japan-themed stereocard sets first started to appear in 1896, but dozens of Japan sets were available just a decade later. These images were no longer tourist souvenirs, but imaginary escapes for people who did not possess the wealth of a world-touring globetrotter. Many of the same images found in Yokohama photography studios and postcards publishers were used to paint an image of the exotic Orient.

In 1903, the novice professional photographer, Herbert George Ponting (1870-1935), was hired by the premier publishers of stereoviews, Underwood & Underwood to take new stereo-photographs of the scenery of Japan. As with many other publishers, he captured the “majestic calm” of the Kamakura Daibutsu.

Originally novelty items that could be paired with parlor games, stereoviews soon started to be marketed as educational tools. Eventually the reverse was filled with descriptive text, often taken directly from tourist books published a decade or more earlier.

From Idol to Icon

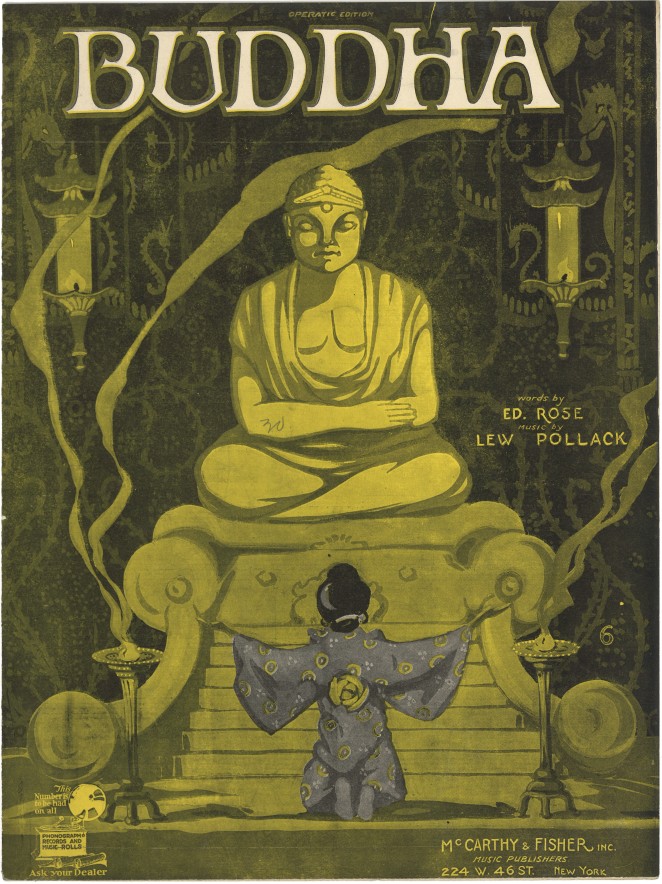

By the first decade of the twentieth century, the image of the Kamakura Daibutsu not only circulated through photographic prints, postcards, and stereoviews – as we have seen already – but also through numerous travel books, magazine articles, and newspaper columns. The image was so often reproduced that it no longer signified a bronze statue, but an amorphous idea, a veritable icon of the exotic Orient.

It is not surprising that such an icon found favor among early modern advertising firms. The growing tourism and cruise ship industry was one of the early adopters of the Kamakura Daibutsu image. The Pacific Mail Steamship company, the first to offer a regular trans-Pacific route from San Francisco to Yokohama in 1867, used it in its magazine ads. Even the Japanese cruise company, Nippon Yūsen Kaisha (NYK) used the Daibutus in their English-language brochures.

The statue also took on more artistic renderings, gracing the cover for the sheet music to “Buddha,” composed by Lew Pollack in 1918 for a Vaudeville act. Lyrics were added the following year by Ed Rose, and it became a popular “foxtrot” dance record for home enjoyment. In addition, the Daibutsu image was also used to add an exotic quality to mundane home goods, such as incense.

The exotic image was also used as a symbol of foreign danger, and can be found in the background of movie sets, such as the Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), reflecting racist and xenophobic undercurrents of American culture. After WWII, the Daibutsu manifested again as popular souvenir trinkets marketed to overseas soldiers, such as cigar ash trays.

The Kamakura Daibtusu continued to be used widely in American advertising throughout the 1950’s, before the allure of the Laughing Buddha started to take a firm hold in the American imagination.

Did You Know?

Both the Laughing Buddha and the Great Buddha of Kamakura are not actually images of the historical Buddha!! They are representations of different buddhas, Maitreya Buddha and Amitābha Buddha respectively – consider taking a Religious Studies class to learn about these figures!

Where’s Waldo?: Did you spot the happy, lounging temple dog that was photographed in both a stereoview and postcard in this exhibition?

[Thank you for your virtual visit!]