Many early Japanese turn-of-the century postcards were colorful illustrations, cartoons, or woodblock prints, some of which were made by famed Japanese artists, but these traditional arts forms would soon lose favor to the photograph. One of the shifts that ushered in the visual dominance of photographic postcards was the introduction of private company postcards 私製はがき, which had been illegal to print until new postal regulations were introduced in 1900. In addition, the adoption of a new photomechanical printing technique, called the collotype, allowed for the wide availability of inexpensive photographic images of Japan.

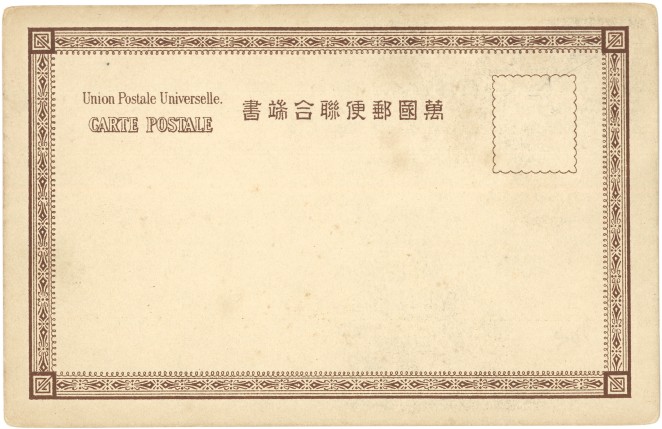

Many early photographic postcards first circulated as albumen or silver gelatin prints sold by commercial photography studios. Early postcard publishers experimented with the orientation of the old images on the new format. By placing the image on the top half of a vertically oriented card, the bottom half could be reserved for the message [Figure 1]. Strategically designed areas or blank spots were necessary on the front of the card, because the reverse of the card was reserved solely for the name and address of the recipient until 1907. The regulations were determined by the Union postale universelle, the body which oversaw the postal system worldwide. These postcards, known today as “undivided back” cards, were replaced by “divided back” cards in 1907 in Japan, where the message could be included on the reverse of the card.

Figure 1

- Title/Caption: NA

- Year: 1900-1907

- Photographer: Tamamura Kōzaburō 玉村康三郎 (1856-1923?)[?]

- Medium: collotype print on cardstock, hand tinted

- Dimensions: 5.5 in X 3.5 in

- Inscription: Union Postale Universelle. CARTE POSTALE, 萬國郵便聯合端書

The image depicts a wide angle view of the Daibutsu taken from the third landing. The positioning of the camera shows the rustic, yet landscaped grounds surrounding the Daibutsu statue. Lacking the presence of people, this bucolic setting exhibits a more quiet moment of the famous tourist destination. On the right, the supports and roof of the ablution pavilion stick out from under an evergreen tree. The water basin (chōzubachi 手水鉢) for washing hands is found underneath (dating from 1749).

The photographer of this image is debated. Older studio albumen prints of this image are imprinted with “661 Daibuthu [sic] at Kamakura.” This numbering is consistent with the studio catalogue of Tamamura Kōzaburō 玉村康三郎 (1856-1923?)(See Bennett 2006: 152), but other sources attribute this image to Ogawa Kazumasa 小川 一眞 (1860-1929). (A similar, but not exact, photo has been identified in an Ogawa studio album). This exemplifies the difficulty in determining the correct attribution and age of old Daibutsu photographs, and more research still needs to be done.

Moreover, because the publishers of the postcard did not imprint their name on the back, it is difficult to tell who printed this tourist souvenir. The reverse of this card is bordered by an ornamental filigree-like design in umber brown ink. This card is an example of an “undivided back,” since no line appears separating the sections on the back where the correspondence and address would later come to be written. This functions now as an easy identifier for dating old postcards, with this exemplar dating between 1900 and 1907. (The photograph was probably taken in the mid-to-late 1890s). In addition, a small scalloped square appears in the top right corner, indicating the location to affix the necessary postage.

*This is part of a series of posts devoted to exploring the development of a visual literacy for Buddhist imagery in America. All items (except otherwise noted) are part of my personal collection of Buddhist-themed ephemera.