The Japanese postal delivery service was initiated in 1871 and soon joined the Universal Postal Union (soon to be known formally as Union Postale Universelle) in 1877, thus permitting the sending and receiving of international mail. Until the start of the twentieth century, however, all postcards were issued by the Japanese government as private companies were prohibited from publishing their own cards. After legal permission was granted in 1900, private companies soon embarked on mass-scale printings of picture postcards (ehagaki 絵はがき). The postcard soon rivaled the traditional woodblock print as the favored medium to present contemporary Japanese images.[1] Furthermore, while many early postcards were illustrated with drawings, photographic images soon dominated the medium and are considered the earliest commodified forms of the photograph.[2] This was spurred by the development of a new printing process, known as the collotype, which allowed for photomechanical printing on a massive scale. Several themes emerged as popular favorites, including ones that may sound odd to modern purchasers of postcards, such as “natural disasters” and “current events.” Not surprisingly, with the advent of the thriving tourism industry, “scenic views” (fukei 風景) emerged as a favorite visual genre for many domestic Japanese tourists and foreign travelers.

Since a driving force behind the early interest in postcards was the acquisition of inexpensive photographs, it seems only natural that several picture postcards would be reprints of old photographic stock. The premier Japanese photographer of his time, Tamamura Kōzaburō 玉村康三郎 (b. 1856), was commissioned in the 1890’s to produce a then-reported one-million hand-colored albumen prints (though more recent estimates place the number of prints at approximately 350,000) for the multi-volume work Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese. He enlisted the help of his competitor, Kusakabe Kimbei 日下部金兵衛 (1841-1934), to finish the massive order. Scholars have only recently begun to identify Kimbei’s photographs found within the publication. The postcard image of the Great Buddha of Kamakura [Figure 1] is now considered a Kimbei photograph. The original image was scaled down and slightly cropped to fit on a standard size postcard.

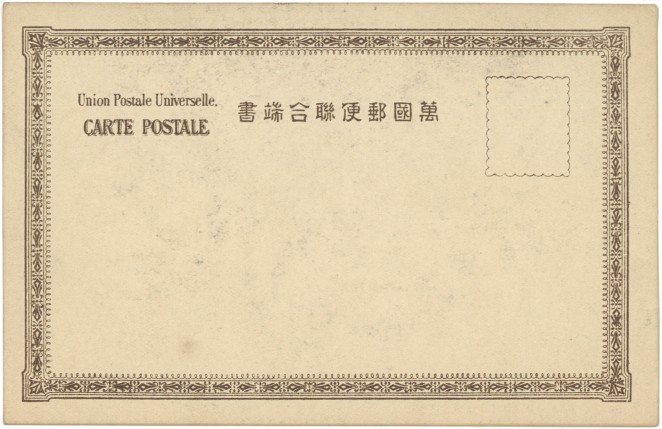

Figure 1

- Title/Caption: NA

- Year: 1900-1907

- Photographer: Kusakabe Kimbei 日下部金兵衛 (1841-1934)

- Medium: collotype print on cardstock, hand tinted

- Dimensions: 5.5 in X 3.5 in

- Inscription: Union Postale Universelle. CARTE POSTALE, 萬國郵便聯合端書

There is no caption identifying the statue or location on the postcard, but the Kamakura Daibutsu was certainly well known in the early twentieth century. In the coming years, however, it would become standard practice to include letterpress captions, often both in English and Japanese, to describe the scene. The fine reticulation pattern and matte cardstock identifies this image as a photomechanical reproduction, known as a collotype (korotaipu コロタイプ). As with standard albumen and silver gelatin photography, early postcards were hand-tinted with water-color washes.

The small margin at the bottom of the card was left for correspondence. Before 1907, the Union Postale Universelle required the entire reverse of the postcard be used for the address and name of the recipient, thus early publishers would leave blank space for a brief messages on the front of the card. Because of this limitation, the correspondence was typically very short, with foreign travelers often briefly commenting on their sightseeing excursions.

The reverse of this card is bordered by an ornamental filigree-like design in umber brown ink. This card is an example of an “undivided back,” since no line appears separating the spaces on the back where the correspondence and address would later come to be written. This functions now as an easy identifier for dating old postcards, with this exemplar dating between 1900 and 1907. In addition, a small scalloped square appears in the top right corner, indicating the location to affix the necessary postage.

Notes:

*This is part of a series of posts devoted to exploring the development of a visual literacy for Buddhist imagery in America. All items (except otherwise noted) are part of my personal collection of Buddhist-themed ephemera.

[1] https://www.mfa.org/collections/asia/art-japanese-postcard

[2] Satō 2002: 41.

References:

- Saitō Takio 斎藤多喜夫. 1985. “Yomigaeru shinsaizen no Yokohama fūkeiよみがえる震災前の横浜風景,” Kaikō no hiroba 開港のひろば, No. 12, pp. 1, 4.

- Satō, Kenji. 2002. “Postcards in Japan: A Historical Sociology of a Forgotten Culture,” International Journal of Japanese Sociology, No. 11, pp. 35-55.

- Yokohama Open Port Museum 横浜開港資料館, ed. 1999. Nen mae no Yokohama Kanagawa ― ehagaki de miru fūkei 年前の横浜・神奈川―絵葉書でみる風景. Tokyō: Yurindo 有隣堂.