After the Meiji Restoration, the popularity of photography began to overshadow traditional Japanese woodblock printing. Increasingly, woodblock artisans came to find employment with photography studios, adapting their technical painting skills to add vivid color to monochromatic photographs. In the beginning of the twentieth century, due to the craze surrounding Japanese picture postcards (ehagaki 絵はがき), artisans continued to ply their trade by adding translucent water-soluble pigments to these small format calotypes. One of the most famous postcard distributers was Tonboya トンボヤ, or the “Dragonfly Studio,” first opened by Yoshimura Kiyoshi 吉村清 around 1905.[1] The Tonboya storefronts in Yokohama, first located in the Isezakichō 伊勢佐木町 district before moving to the more heavily trafficked Motomachi 元町 district, were easily identifiable because of large signboards made to look like red cylindrical postal boxes (yūbin posuto 郵便ポスト) widely adopted in Japan. One side of the signboard had the word “POSTALCARDS” painted on it, while the other said ehakaki エハカキ [sic](“picture postcards”), suggesting Yoshimura catered to both foreign and domestic travelers.[2] One image that would represent the photographic interests of both groups would be the Kamakura Daibutsu, located close to the port of Yokohama [Figure 1].

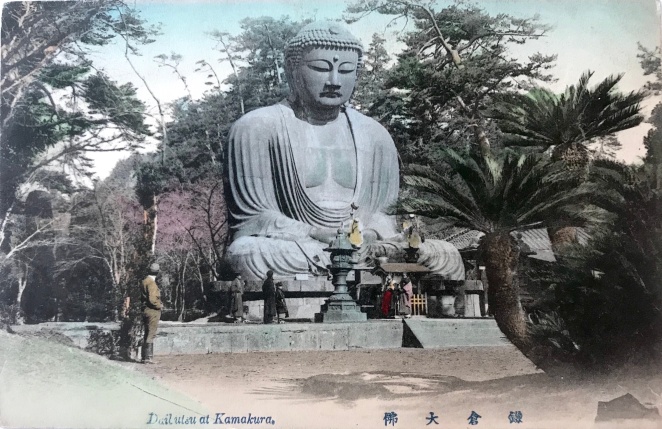

Figure 1

- Title/Caption: Daibutsu at Kamakura. 佛大倉鎌

- Year: 1907-1918

- Publisher: Tonboya トンボヤ

- Medium: collotype print on cardstock, hand tinted

- Dimensions: 5 in X 3.5 in

- Reverse Imprint: Union Postale Universelle.[+], 郵便はかき

By setting the camera on the second landing of the paved walkway, this unknown photographer filled the frame with the image of the Daibutsu; positioning the statue frontally and symmetrically, this framing is similar to many of the images produced by Yokohama photography studios. The image depicts three figures, two women and a young child, facing the Buddhist icon in the center of the photograph. This setting might elicit other images of religious piety at this site, but the mise-en-scène is complicated by the presence of two more children, standing at each of the sides, who stare directly at the viewer. Their presence might have been obscured had it not been for the colorist who painted them in light hues of blue and pink. Notably, their casual posturing is stark contrast to staged “photo ops” of foreign travelers who try to visually suggest their domination of the Orient. Because of these elements, on the whole, we are made to feel as if the scene is staged and that we have been caught in an act of voyeurism. The women and child, positioned center-stage, engage in a orchestrated religious performance while the children at the edges observe us watching them. A rather apt visual metaphor for the Orientalist gaze, where the artist attempts to create a certain controlled vision of the East, but with “unruly” actors foiling the illusion.[3]

This postcard is not imprinted with a trademark to identify the publisher. The black ink and serif font used for the reverse, however, in addition to the guide lines provided for writing the address, all suggest this card was made by Tonboya.[4] In addition, the position of the diving line for correspondence indicates this card was printed between 1907 and 1918. If the image on the obverse was not self-evident enough, bilingual cerulean letterpress (note the impression the reverse) identifies the scene clearly: “Daibutsu at Kamakura.”

Notes:

*This is part of a series of posts devoted to exploring the development of a visual literacy for Buddhist imagery in America. All items (except otherwise noted) are part of my personal collection of Buddhist-themed ephemera.

[1] Several online English sources claim Tokutaro Maeda was the founder of Tonboya, but I have found no Japanese sources that confirm this. I prefer here to follow the print Japanese sources (e.g. Saitō 1985: 1), but leave the question unsettled.

[2] Several early-century postcards depicting the streets of Yokohama show this red cylindrical signboard, as seen here:  The full postcard can be found here (not part of the Archive).

The full postcard can be found here (not part of the Archive).

[3] By shooting one woman mid-stride ascending the small flight of steps, this photographer is (accidentally?) paying homage to Enami Nobukuni 江南信國 (1859—1929), but without the overal effects of sterling visual narrative.

[4] The best site for identifying Tonboya cards remains here: http://tamayochankankousya.seesaa.net/article/421306802.html. Another common reverse printing of Tonboya during this period is discussed here.

References:

- Handy, Ellen. 1998. “Japonisme and American Postcard Visions of Japan,” in Delivering Views: Distant Cultures in Early Postcards, Christraud M. Geary and Virginia-Lee Webb, eds. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Saitō Takio 斎藤多喜夫. 1985. “Yomigaeru shinsaizen no Yokohama fūkei よみがえる震災前の横浜風景,” Kaikō no hiroba 開港のひろば, No. 12, pp. 1, 4.

- Satō, Kenji. 2002. “Postcards in Japan: A Historical Sociology of a Forgotten Culture,” International Journal of Japanese Sociology, No. 11, pp. 35-55.

- Yokohama Open Port Museum 横浜開港資料館, ed. 1999. Nen mae no Yokohama Kanagawa ― ehagaki de miru fūkei 年前の横浜・神奈川―絵葉書でみる風景. Tokyō: Yurindo 有隣堂.