Introduction

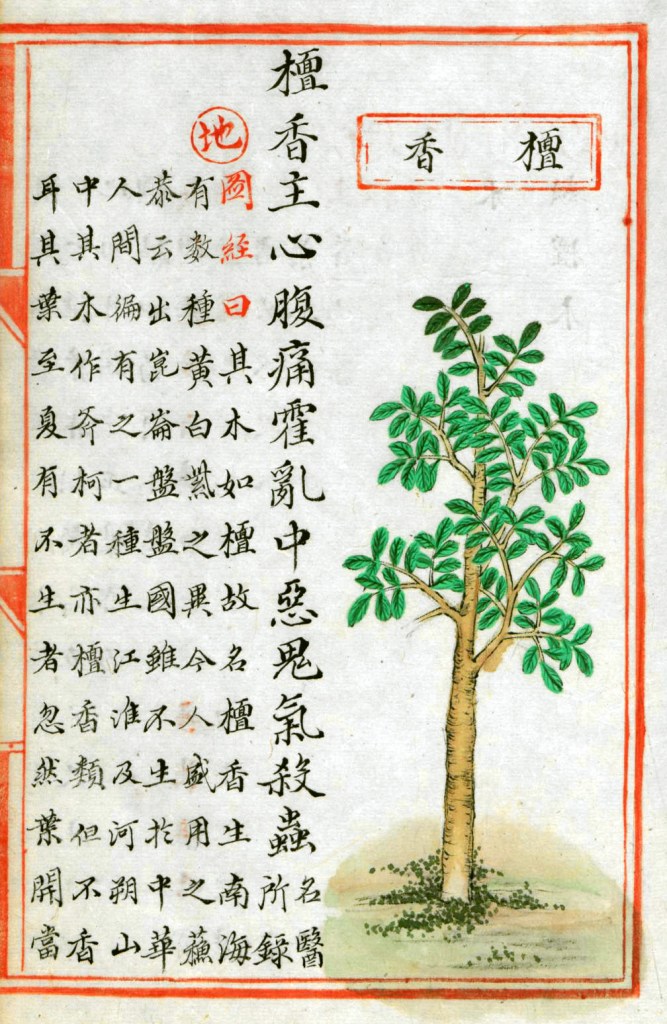

Known for its characteristic earthy and warm scent, sandalwood is arguably the most common aromatic used in South Asian religious practice. The term sandalwood most typically refers to the fragrant heartwood of the Santalum album tree, although other Santalum species produce wood historically traded under the name sandalwood. Due to different levels of oil saturation, sandalwood’s color ranges from pale yellow to brownish red. Moreover, because the oil helps in preservation and due to the wood’s naturally close grain, sandalwood is also ideal for making finely carved objects. The heartwood closest to the tree root contains the most oil, consequently sandalwood harvesting typically requires the destruction of the tree. Curiously, the S. album tree may not have been native to southern India, but was indigenous to the eastern parts of the Indonesian archipelago. Archaeobotanical wood charcoal remains, identified as Santalum, were found in the southern Deccan and have been dated to ca. 1300 BC, suggesting the tree was cultivated by humans very early in southern India. When sandalwood was introduced to China sometime during the Han Dynasty, the Chinese apparently considered it a type of native rosewood and used that tree’s name, tan 檀, to translate the foreign aromatic wood.

Facts and Features

- Medieval Chinese Name: “Rosewood” Aromatic (tan xiang 檀香), Chantan Aromatic (chantan xiang 旃檀香; approximating Sanskrit candana)(among others)

- Common English Name: sandalwood

- Botanical Origin: oil-saturated heartwood of several species in the Santalum genus, but most typically the Santalum album tree

- Phytogeographic Distribution: (S. album) Indonesian archipelago (eastern Java, Lesser Sunda Islands, and Timor), cultivated in southern India [approximate distribution* is shown in orange below]

- Harvesting Process: Yellowish fragrant heartwood is cut away from the lighter colored, non-scented sapwood; this processes often requires the destruction of the tree as the greatest concentration of oil is near its base and especially in its roots

- Earliest Chinese Citation: late 2nd century (in translated Buddhist sutras: e.g. Daodi jing 道地經 (Yogācārabhūmi)[possibly earlier Western Han sources?]

- Earliest Chinese Medicinal Use: late 5th century (Collected Annotations on the Classic of Materia Medica of the Divine Husbandman [Shennong bencao jing jizhu 神農本草集注])

Comments: Despite the cultural and religious prominence of sandalwood in medieval India, especially among Buddhists, Chinese citations to this important aromatic are relatively sparse well into the fifth century. This comes into a more stark relief when compared to early Chinese citations to Mediterranean storax, Moluccan cloves, Vietnamese aloeswood, Arabian frankincense, and Indian costus root during this same period. Even into the Tang, the source of imported sandalwood, either from southern India or the eastern end of the Indonesian archipelago, remain obscure in Chinese sources. Nevertheless, this should not be mistaken for total ignorance, as sandalwood emerges in China as an important religious and artistic medium, especially with the circulation of the legend of the Udayana Buddha sandalwood image starting at the end of the fourth century.

If we turn to the Classified Essentials of Materia Medica (Bencao pinhui jingyao 本草品彙精要) from 1503 we find an illustration of the sandalwood tree. It bears a resemblance to the relatively small S. album of Southern India with lanceolate-elliptic leaf anatomy.

Older scholarship had claimed sandalwood was cited in the Old Testament as a building material for Solomon’s temple, but this view has largely been abandoned. Equally, the claim that Egyptians employed sandalwood during the embalming process of mummies was poorly documented and has been rejected as unlikely. Turning to Greek and Roman sources, the purported citation to sandalwood in the first century Periplus Maris Erythraei has recently been emended, with good evidence, to teak. It also appears neither Pliny nor Dioscorides mention sandalwood in their first century works. Based on the strongest available evidence, it is only in the mid-sixth century when the Alexandrian Greek merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes indisputably refers to Indian sandalwood.

The Sanskrit term for sandalwood, candana, has long textual history in India and can be found in Yāska’s Nirukta which was compiled before the third century BCE. In the final compilation of the Arthaśāstra, conservatively dated to the first century, sixteen different types candana are listed (all may not properly refer to sandalwood). In terms of use, both the Mahābhārata and the Ramāyaṇa, which may be of a later date, speak of candana made into a paste and smeared on the body.

* The map is intended as a general heuristic for distribution and range, it reflects selected data from modern scientific research and descriptions from medieval Chinese materia medica and gazetteers

For further information and additional references, see: Peter M. Romaskiewicz, “Sacred Smells and Strange Scents: Olfactory Imagination in Medieval Chinese Religions.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2022.