The Buddhas in the West Material Archive exhibit, entitled “Victorian Virtual Travel: Visions of Buddhism,” is featured at the San Diego Central Library through November 2024.

Welcome to the Companion Guide

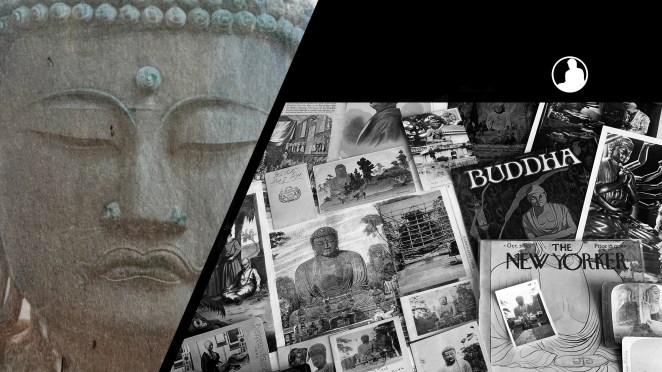

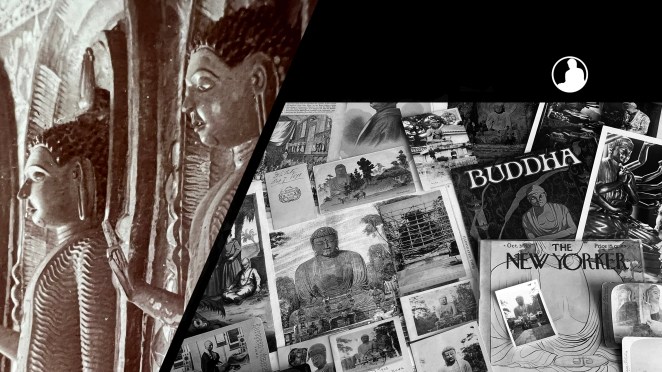

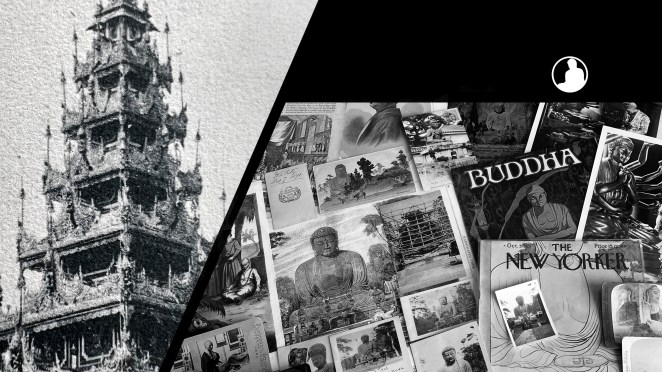

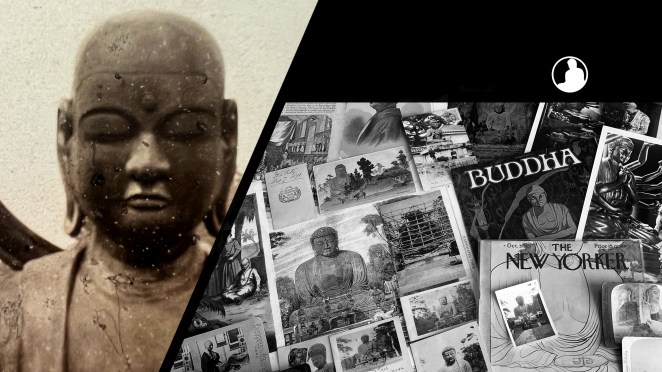

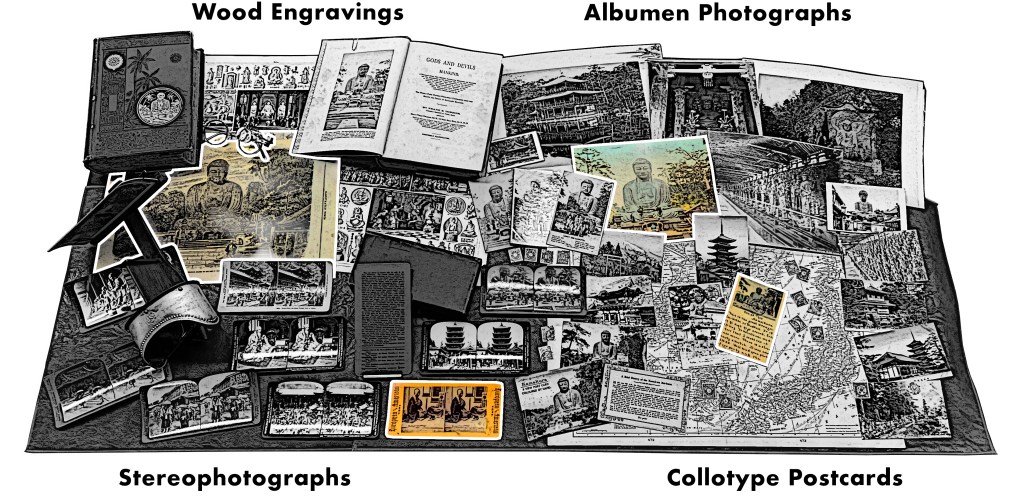

The exhibit contains forty artifacts that helped transport Victorian-era Americans to Japan through emerging print technologies at the end of the nineteenth century. Consequently, artifacts like these helped shape an early American visual literacy of Buddhism.

The display is roughly divided into four sections comprising engravings, hand-colored photography, stereophotography, and hand-colored postcards.

As you explore, what items stand out to you the most? Can you imagine stories or adventures a traveler might have imagined when viewing these objects? What can you learn about Buddhism through these items? Does any artifact or imagery challenge what you currently know about Buddhism?

Four Types of Victorian Visual Media

Wood Engravings

Materials related to mass publication engravings are found in the top left of the display case. The change from copperplate engravings to wood engravings revolutionized nineteenth century print illustration. By engraving the tight endgrain of boxwood blocks, illustrators could capture more details than regular woodcuts. Moreover, illustration blocks could now be inserted into the same form as type, considerably speeding up the printing process and giving birth to illustrated daily newspapers in the 1840s. The wood engraving of the Kamakura Daibutsu highlighted above was published by the Illustrated London News in 1868 and exemplifies the kind of illustrations seen in illustrated newspapers of the day. Many Victorian-era Americans first discovered Buddhist imagery though illustrated periodicals, travelogues, and other books.

Albumen Photographic Prints

Materials related to albumen photographic prints are found in the top right of the display case. Early photography employed a time-consuming wet-plate method which required photosensitive chemicals to be mixed, applied to a glass negative plate, exposed, and developed in a portable dark room in quick succession. The subsequent photograph was printed on paper coated with an emulsion of egg white, called albumen, giving rise to the name albumen print. Photography studios first opened in Japan in the 1860s, providing foreign travelers the opportunity to return home with souvenirs of sites they visited. The easier dry-plate method of photography was introduced into Japan by the 1880s and Japanese-owned studios began to overtake the souvenir market. The photograph of the Kamakura Daibutsu highlighted above was taken by Italian-born Adolfo Farsari (1841–1898) who opened a studio in Yokohama in 1885. As was common for larger formats, albumen prints were hand-colored and Farsari’s Japanese artists were known for creating some of the most brilliant palettes.

Stereophotographic Prints

Materials related to stereophotography are found in the bottom left of the display case. Stereophotography uses a pair of photographs taken from slightly different horizontal positions – typically the distance between a person’s eyes – to produce an illusory sense of depth when viewed through a stereoviewer. Stereocards first emerged as a popular form of entertainment in the 1860s, most often used as a home parlor room activity. At the end of the nineteenth century stereoview companies started to shift focus from entertainment to education and began publishing stereoview sets highlighting different regions of the world. The stereocard view of a Buddhist priest highlighted above reflects the variety of scenes and people introduced to Americans through this popular education and entertainment medium.

Collotype Postcards

Materials related to postcards are found in the bottom right of the display case. The Golden Age of postcards spans roughly from 1890–1915 and due to their inexpensive nature are sometimes considered the first “democratic” photographic medium. Postcards were not just mailed as souvenirs during this period, they were also collected in albums and shared with friends and family as a pastime. Moreover, the 1905 Russian-Japanese War caused a “postcard boom” in Japan, thus creating one of the largest postcard producers and consumers in the world. Translating the tonality of a photograph to black ink was accomplished through several methods by the end of the nineteenth century, but the gelatin-based collotype process was favored by Japanese postcard publishers. It created a fine reticulated “wormy” pattern that is barely visible to the naked eye. The collotype postcard of the Kamakura Daibutsu highlighted above bears a message from the sender. A majority of the postcards shown here were hand-colored, most likely by Japanese women working from home, and were intended for both domestic and foreign audiences.

Exhibit Introduction

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: