Introduction

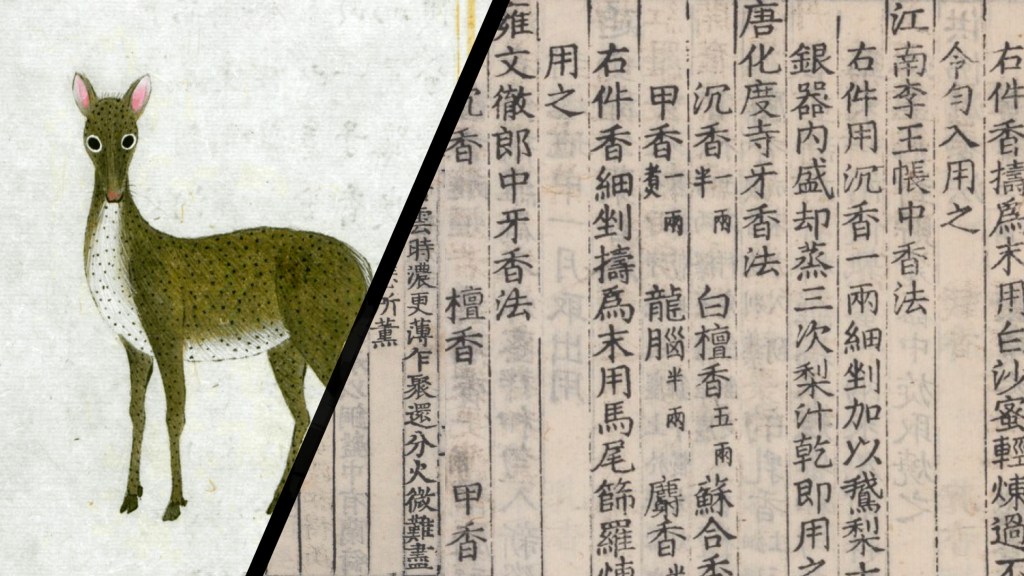

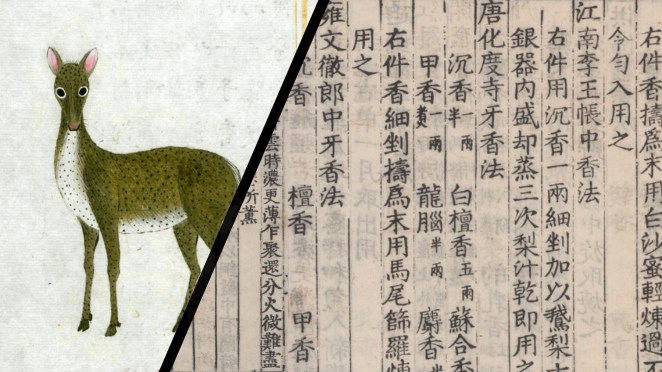

Musk is among the most expensive materials derived from an animal, worth more by weight than gold. The intensely scented dark granular paste comes from the male musk deer of the genus Moschus. Produced by a scent gland on the abdomen, the deer uses the scent to attract mating partners and mark territory. The smell of musk is pungent with a warn and powdery, yet bitter, scent profile. Its chemical characteristics translated into its use as a fixative in medieval perfumery which continues through today. Several species of musk deer are native to the forested Chinese highlands: the M. berezovskii has the greatest range in China, spreading from western central China down into northern Vietnam, the M. sifanicus covers some of this range and extend into the Tibetan plateau, the M. fuscus and M. chrysogaster roam the Himalayas and eastern Tibet, and the M. moschiferus lives in north China. In the early medieval period the Chinese knew the musk deer as primarily inhabiting the regions of Shaanxi, southern Gansu, Sichuan, and Yunnan, all regions far from the old capital cities in the Central Plain. Consequently, musk retained a sense of the semi-exotic in the medieval period.

Facts and Features

- Medieval Chinese Name: musk (she xiang 麝香)

- Common English Name: musk, deer musk

- Animal Origin: paste derived from the dried contents of the preputial scent gland of several species in the Moschus genus

- Range: Himalayan region (Northern India, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet), northern Myanmar, northern Vietnam, southwestern China, western central China, north China [approximate range* of musk deer is shown in lavender below; range of M. moschiferus extends northward to Arctic Circle]

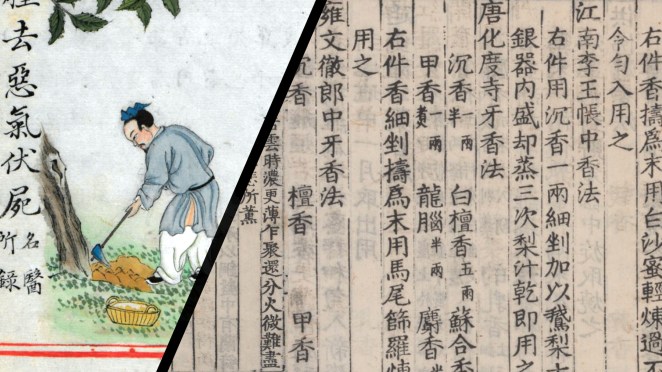

- Collection Process: male musk deer is captured and killed, then the scent gland is removed and dried, turning the interior into a dark granular paste

- Earliest Chinese Citation: 3rd–1st century BCE (lexicographic work: Approaching Elegance [Erya 爾雅])

- Earliest Chinese Medicinal Use: 1st c. BCE – 1st century CE (Classic of Materia Medica of the Divine Husbandman [Shennong bencao jing 神農本草經])

Comments: The Chinese character for musk is found among the oracle bone corpus and a simple graphemic analysis shows a bowhunter shooting an arrow (she 射) and a deer (lu 鹿). The interpretation offered by Li Shizhen in the sixteenth century is that the musk deer projects, or shoots (she), its fragrance over a long distance. Chinese texts have the earliest citations to musk, but they appear with greater frequency around the turn of the common era. For example, musk does not appear in the traditional ritual canon of the Shang and Zhou, nor does it appear in the Mawangdui medical manuscripts from the second century BCE. Starting by at least the first century (if not earlier), musk is regularly encountered in prescriptions, formularies, and materia medica throughout the medieval period. For example, the early fourth century herbalist Ge Hong considered musk one of approximately two dozen drugs to have constantly on hand and prescribed the use of musk pellets to repel snakes in the mountains.

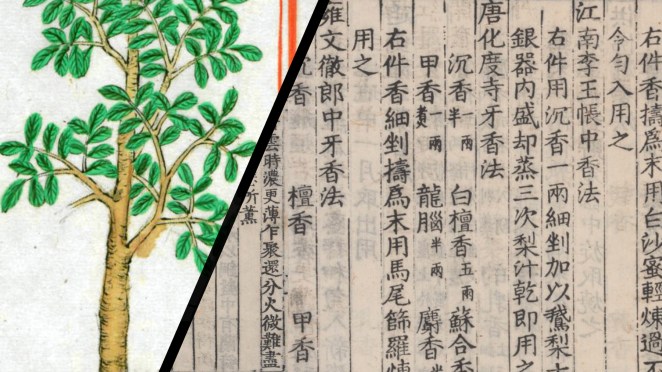

If we turn to the Classified Essentials of Materia Medica (Bencao pinhui jingyao 本草品彙精要) from 1503 we find an illustration of the musk deer. It is depicted accurately without antlers and upon close inspection we can find two small canine tusks jutting downward from the mouth.

Musk does not appear in Indic textual sources until a few centuries into the common era. This is somewhat surprising given the musk deer roamed the Indian side of the Himalayan range. Musk is also missing from classical Greek and Latin sources, including the first century Periplus Maris Erythraei, a handbook of Greco-Roman trade. Looking first at India, musk is found in the Caraka Saṃhitā, but it appears in a section that may reflect the last stratum of composition sometime around the fourth or fifth centuries. The seventh century Harṣacarita contains a clear reference to musk using what became the standard Sanskrit term kastūrī.

Curiously, however, kastūrī is a loanword from the Greek castoreum, which refers to a different animal-derived aromatic. How a Greek term came to name a natural material available in the Himalayas is difficult to understand, but it was perhaps Greek trade that spurred or supported an early Indian interest in musk. The earliest Western Asia reference to musk possibly does not come until the Byzantine Empire, such as we see in the writings of the mid-sixth century Alexandrian Greek merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes. Otherwise, another early citation to musk outside Chinese sources is found in the collection of Sogdian letters recovered in the Tarim Basin and dating to the early fourth century. Musk was included as one of the items of Sogdian trade, suggesting Sogdian merchants could have been one of the early bridges taking musk westward from China and Tibet.

* The map is intended as a general heuristic for distribution and range, it reflects selected data from modern scientific research and descriptions from medieval Chinese materia medica and gazetteers

For further information and additional references, see: Peter M. Romaskiewicz, “Sacred Smells and Strange Scents: Olfactory Imagination in Medieval Chinese Religions.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2022.