Download a PDF of this webpage here!

Revised Summer 2024

What is a material analysis?

A material analysis closely inspects an artifact’s material and sensorial qualities and asks questions about its use and significance. Oftentimes, the data gathered supplements more traditional disciplinary methods, such as data gathered from textual analysis.

Starting in the 1980s disciplines like anthropology, archaeology, and art history – all areas with close ties to objects and museums – began to explore more complex relationships between the “cultural” and “material.” Consequently, material artifacts, especially commonplace objects of daily use (like the postcard pictured here), were viewed as not only reflecting important social values and identities, but also as mediating human behavior. A material analysis attempts to reconstruct how and why objects were used, often resulting in a more complex interpretation of human behavior.

Why might we want to perform a material analysis?

For one, objects tell us about the lives and experiences of people. Sometimes this may add to or complicate our understanding of an historical event or biographical narrative. At other times, this may contradict our presumptions and reveal new paths of inquiry.

Second, a material analysis also reveals to us that objects have their own “life story.” As artifacts move from one person’s possession (or spatial and/or cultural context) to another, their value, use, and meaning may change even if their form changes little. Charting such changes is oftentimes called a “cultural biography” of an object.

Lastly, because people are enmeshed in a physical world, a material analysis reveals how objects help structure human activity in particular ways. For example, a large sun-lit cathedral hall will provoke different emotions and behaviors than a dark cave. Likewise, a sharp obsidian stone will shape a person’s response differently than a fluffy pile of goose down. In these cases, scholars have argued objects have agency because their materiality shapes human activity and subjectivity.

How do we perform a material analysis?

At one level, we examine the material properties of an artifact. This is best done with an object physically accessible to pokes and prods. This is a primary type of material analysis that directly inspects objecthood.

A secondary kind of analysis can be performed with care upon objects we access only by some kind of representational form, such as a photograph of the target artifact. This may be necessary if the artifact has been lost or destroyed or remains beyond our touch because it is hidden, restricted, or otherwise inaccessible. This may require amassing several visual documents (or written descriptions) to compile a more complete assessment of the target artifact. To take the postcard above as an example, one could use it as one documentary source to try and study the icon it depicts, the Kamakura Daibutsu. It would be more typical, however, to study the object at hand, namely the postcard itself.

On another level, we also analyze the various networks of materiality that support and give meaning to an artifact. This means we also pay attention to how an object was made and by whom. Furthermore, we also examine who uses the object and for which purpose. It may be the case that we can infer some of these answers by closely inspecting the object and applying our general knowledge. Often, however, questions of production, consumption, and signification require additional research beyond inspecting objecthood.

Overall, there is no codified set of questions for a “proper” material analysis, although we typically start with our senses and extend outward to broader and more complex layers of social and intercultural meaning. [I’ve also prepared a list of 88* Questions to Ask an Artifact]

What can we do with a material analysis?

A close investigation of an artifact will provide the groundwork for your own interpretations. A material analysis can inform something as brief as a museum label. But just because museum labels are short by convention does not mean they are insignificant. Labels tell us how to interpret an artifact: should we see it as a curious anthropological object or as a piece of art? To use the postcard from above, should we frame it as a quaint, hand-written souvenir from the turn of the century or as a highly-technical hand-colored collotype print?

In addition, a material analysis can be used to compliment or complicate interpretations based on different materials and documents. For example, we may ask if American tourists to the Kamakura Daibutsu in the early twentieth century envisioned it as a sacred icon or as a piece of art. The inscription on the postcard here documents the statue’s dimensions and material composition, suggesting the visitor appreciated the craftsmanship over its sacredness. This can lead to different kinds of questions such as comparisons to Daibutsu talismans that were also sold on site to Japanese pilgrims.

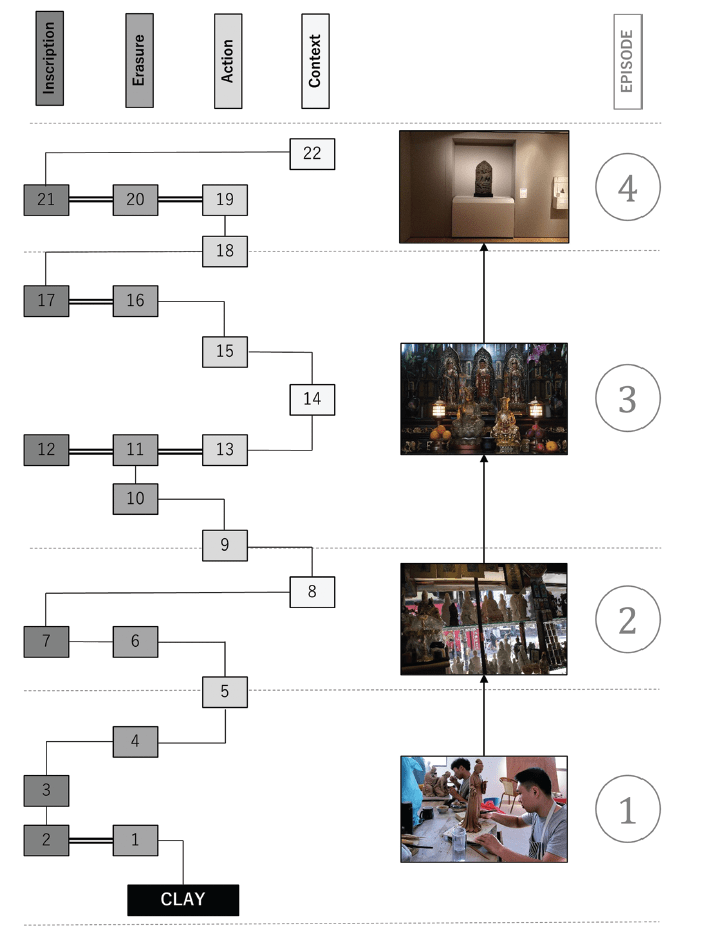

It is also possible to do a more extensive report on an object (or class of objects) in the vein of an “object biography.” In such a case it is important to consider how artifacts may go through different life episodes as they are modified and re-purposed throughout their lifespan. Chip Colwell has recently published an excellent overview of how one might envision this process. In his example, Colwell divides the lifespan of a Buddhist Guanyin statue into four episodes: its creation process, being sold in a store, being used as a ritual icon, and being displayed in a museum (see diagram).

During each stage the artifact can be modified (things are added/inscribed or taken away/erased), different actions are performed in service to it, and it is placed in different spatial and interpretive contexts. Such a perspective allow us to see that as artifacts enter new life stages they typically accumulate new layers of meaning, value, and status.

* See Chip Colwell, “A Palimpsest Theory of Objects,” Current Anthropology 63, no. 2 (2022): 129–57, https://doi.org/10.1086/719851.

*This handout was originally prepared by Peter Romaskiewicz as part of a university course that explored religion and material culture. Feel free to use and/or adapt to your needs. Email: peter.romaskiewicz@gmail.com.

Related Posts