Introduction

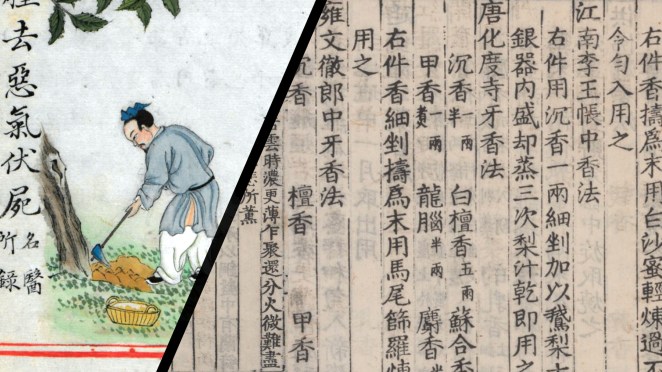

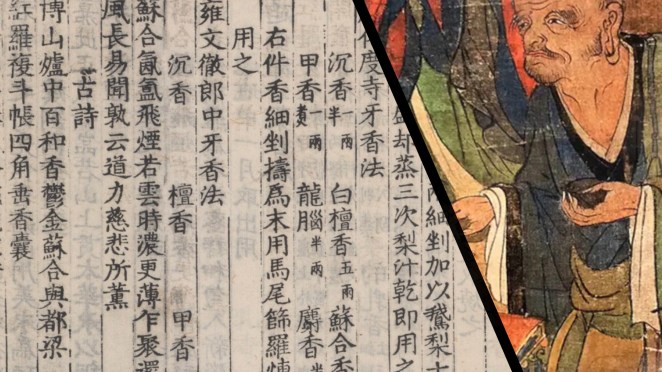

The “Recipe for Blended Incense from Tang Huadu Temple” (Tang Huadu si yaxiang fa 化度寺牙香法) is first recorded in Hong Chu’s (1066–c.1127) Materia Aromatica (Xiang pu 香譜). Hong Chu’s text is the earliest extant Chinese perfuming catalogue and was compiled in the early twelfth century. The six-ingredient recipe (plus honey) is shown here as it appears in the two fascicle Materia Aromatica preserved in the Baichuan xuehai 百川學海 collectanea originally published in 1273 (the image here is from a xylographic print issued after 1501).

Buddhist blending recipes are also scattered throughout the Chinese Buddhist canon, but nothing precisely matches the one recorded by Hong Chu during the Song. Furthermore, there are other Huadu Temple blends preserved in later medieval Japanese perfuming catalogues, yet these contain additional ingredients. Thus, we are left to presume the recipe discussed here is a genuine Tang-era artifact associated with the famed Buddhist Huadu Temple.

Facts and Features: Huadu Temple

The Huadu Temple (Huadu si 化度寺) was a monastic compound located in the medieval capital city of Chang’an, present day Xi’an. The temple grounds were located in the northwest part of the city, positioned east of the southern gate to Yining Ward [red circle on map]. This location was not far from the famed Western Market where foreign merchants sold and exchanged exotic imported goods [blue box on map].

The temple was first constructed as Zhenji Temple (Zhenji si 真寂寺) in 583. It was renamed Huadu Temple under the first Tang emperor in 619. Then in 846, after rebuilding in the wake of the Huichang Persecution of Buddhism, the monastery complex was renamed Zhongfu Temple (Zhongfu si 崇福寺). If we are to take the name of the blending recipe at face value, we can presume it became closely connected to this Buddhist site between 619 and 846 when the monastery was still named Huadu Temple.

During the Sui and early Tang the wealth of Huadu Temple was considerable and well-known among all in the capital. This was the location of the Inexhaustible Storehouse (wujin zangyuan 無盡藏願), a treasury used to pay for the repair of temples and monasteries all over the country and to provide loans to the subjects of the capital. The treasury was confiscated by the imperial house in 721. Following this seizure the temple never returned to its former wealth and glory. For the sake of discussion, I will speculatively hold the Huadu Temple blending recipe dates approximately to the year 700, before the temple lost is vast holdings. Moreover, it is during this time when Huadu Temple held its No-Barrier Festivals, great public celebrations of generosity held under the auspices of the imperial house. As we will see, the combination of exotic aromatics clearly signals wealth and conspicuous consumption.

Translation

Recipe for Blended Incense from Tang Huadu Temple 唐化度寺牙香法

| aloeswood | 1½ liang* | 沈香 | 一兩半 |

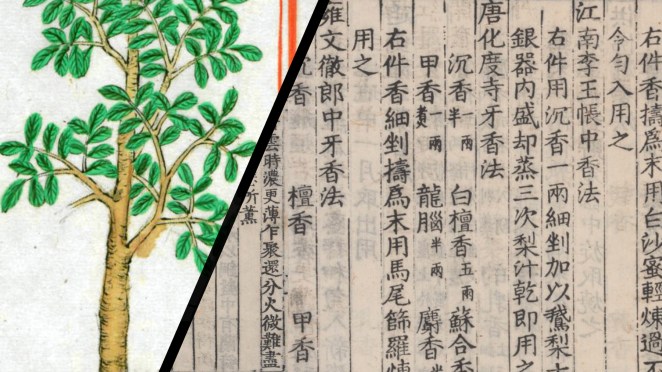

| sandalwood | 5 liang | 白檀香 | 五兩 |

| storax | 1** liang | 蘇合香 | 一兩 |

| onycha | 1 liang (reduced) | 甲香 | 一兩煮 |

| camphor | ½ liang | 龍腦 | 半兩 |

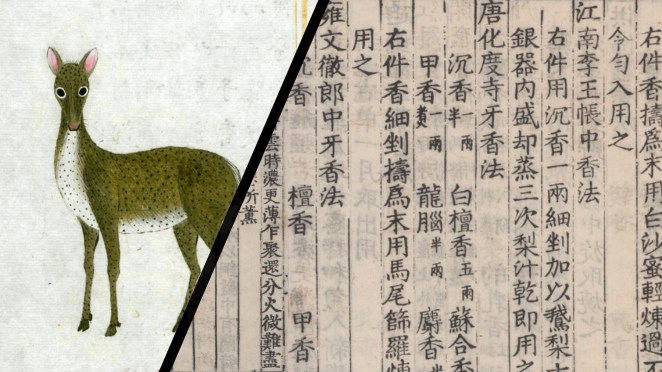

| musk | ½ liang | 麝香 | 半兩 |

File and grind the above aromatics into a powder. Use a horse tail mesh to sift. Incorporate and mix with refined honey, then it is ready to use.

右件香細剉擣為末,用馬尾篩羅,煉蜜溲和得所用之。

*During the Tang, one liang, the “Chinese ounce,” was equivalent to 1.31 ounces (37.3 grams)

**Listed as 2 liang in the Newly Compiled Materia Aromatica (Xinzuan xiang pu 新纂香譜)

Comments: The Huadu Temple blend is a historical snapshot of exotic aromatics circulating in China during the height of the Tang Dynasty. Storax came from the Mediterranean (violet on map below), camphor likely came from the Malayan Peninsula (crosshatched white), sandalwood likely came from southern India (orange), and aloeswood likely came from the tropical south in the vicinity of present-day Vietnam (blue). Musk, from the musk deer, probably arrived from the mountains of the Tibetan and Yungui plateaus (lavender), while onycha was made from gastropod mollusks found along the coasts of southeastern and southern China and the Gulf of Tonkin (light blue). Chang’an (red dot) was connected to all of China’s major cities through a network of roads and canals which further channeled foreign goods from distant markets and ports. (Areas of distribution* overlap are barred.)

In the medieval world, aromatics were also part of larger webs of significance that might go overlooked from our modern vantage point. For example, all of the raw materials in the Huadu Temple blend are found in the Newly Revised Materia Medica (Xinxiu bencao 新修本草) published in 659. Consequently, in addition to scenting the air, each material was also believed to have therapeutic properties. Within this pharmacological context, however, these drugs would typically have to be ingested as there is no recorded medieval Chinese practice of aromatherapy in the modern sense. If we broaden our scope to a wider range of medieval textual genres, including translated Buddhist scriptures, regional gazetteers, and dynastic histories, all of the aromatic ingredients appear to have been known in China by the early fourth century. In such cases they appear as ritual items of religious power, tributary gifts from foreign states, and regional commodities of high economic value. The six-ingredient Huadu Temple blend thus helps provide a glimpse into a vast supra-regional trade flowing into medieval China as well as the multiple layers of significance reflected through possession of these aromatics.

* The map is intended as a general heuristic for distribution and range, it reflects selected data from modern scientific research and descriptions from medieval Chinese materia medica and gazetteers

For further information and additional references, see: Peter M. Romaskiewicz, “Sacred Smells and Strange Scents: Olfactory Imagination in Medieval Chinese Religions.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2022.