Arguably, the most famous singular piece of aloeswood in the world is held by the Shōsō-in 正倉院, the imperial Japanese treasury located at the famed Buddhist temple Tōdai-ji 東大寺 in Nara. This golden-colored piece of resinous wood with dark exterior is 1.56 meters long and weights 11.6 kilograms. Historically in Japan, unique fragrant materials categorized as meikō 名香, “famous aromatics,” were bestowed distinctive names. It is therefore commonly believed that upon entry into the Shōsō-in this piece of aloeswood was adorned with the name ranjatai 蘭奢待.

The ranjatai is sometimes praised in Japanese as the “World’s Most Famous Aromatic.” This is despite the fact this aromatic wood is rarely shown to the public and has an obscure history dressed in popular lore.

Part of the lasting interest in the ranjatai stems from its curious name. The word ranjatai inconspicuously hides the name of Tōdai-ji within its graphs (see above). One circulating story claims it would have been inauspicious to borrow the name of a prominent Buddhist monastery for naming a piece wood that would be burned as incense. Thus, using the characters for ranjatai was viewed as an elegant solution to honor the temple’s name while not indirectly threatening its safety.

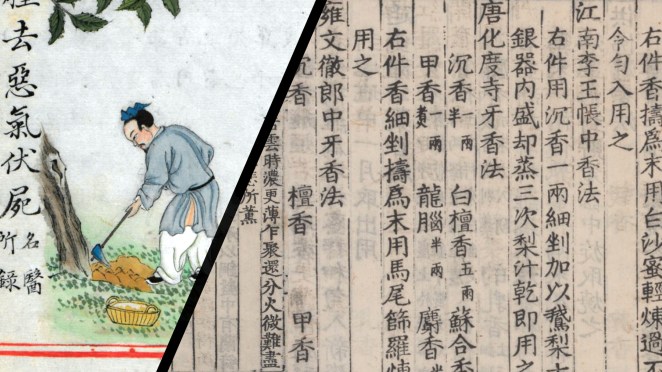

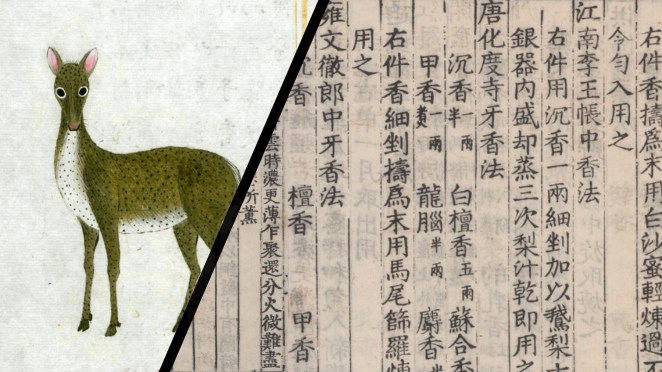

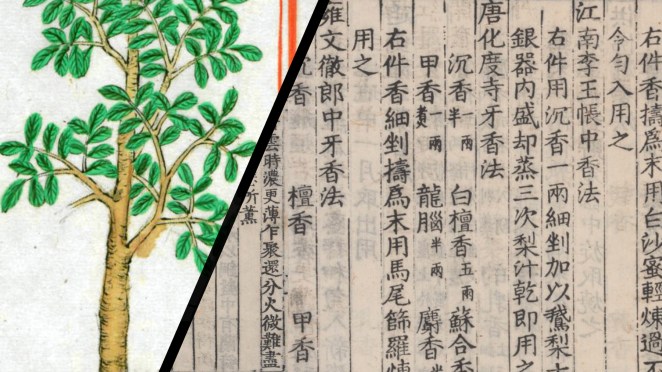

Materially, the ranjatai is a large piece of aloeswood. Aloeswood is one of the most expensive materials by weight with higher quality pieces worth more than gold. This cost is directly related to its rarity. Aloeswood is a fragrant resin-infused wood that forms in several species of the Aquilaria tree growing across the tropical regions of southeast Asia. This fragrant material is only formed under certain conditions, typically when the tree is stressed by environmental, biotic, or abiotic factors. Consequently, not all Aquilaria trees contain aloeswood, making it among the most rare commodities for incense and perfume blending. (For more on aloeswood in medieval China, read this post.)

According to one of the more prominent stories circulating, this large piece of aloeswood was originally in possession of Emperor Shōmu 聖武 (r. 724–748) who received it as tribute from China. Accordingly, some believe the ranjatai was donated by Empress Kōmyō (701–760) upon the death of the abdicated emperor in 756. The many donations given by the empress form the foundation of Shōsō-in’s collection today. A more nuanced take claims that during a state protection ritual at Tōdai-ji in 753 the ranjatai may have been gifted as an act of pious generosity. Proponents point out this practice was documented for another rare piece of aloeswood held by the treasury. A related circulating story claims the ranjatai was originally in the possession of Empress Suiko 推古 (554–628) after the wood drifted ashore in 595. This appears to be a further elaboration of a story contained the Chronicles of Japan (Nihon shoki 日本書紀) where a piece of aloeswood, found by locals along the beach of Awaji Island, was gifted to the Empress. This story is often treated as the origin of incense in Japan. It should be noted this story is sometimes associated with a different famous aromatic once known as the taishi 太子 in possession of Hōryū-ji 法隆寺.

Such incongruity in origin stories not only underscores the importance of the ranjatai, but further preserves it as a topic of debate and conversation among the public. The history of the ranjatai is perhaps most embellished by the fact that a few of the most politically important figures in Japanese history have reputedly cut off small portions for their personal use. This includes shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa 足利義政 (1436–1490), daimyō Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (1534–1582), and Emperor Meiji 明治天皇 (1852–1912). For example, imperial records from 1877 note that when Emperor Meiji burned a small piece, “fragrant smoke filled the palace.” In these scenarios, having access to the imperial storehouse, especially for those who did not sit on the Chrysanthemum throne, was viewed as a sign of true political power.

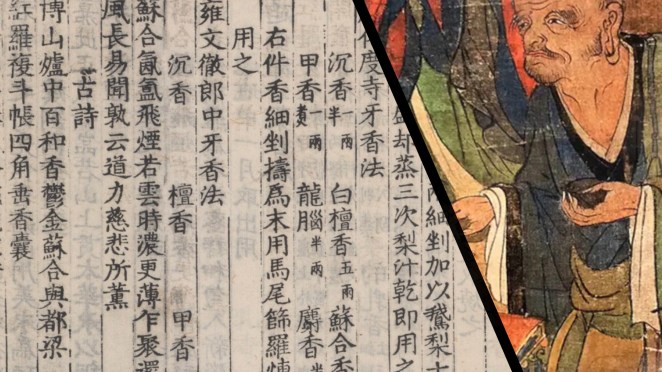

There have been few attempts in the modern era to capture the likeness of the ranjatai. The first record comes to use from when the treasury was opened in 1693 for repairs. During the summer, the chief priest of Tōdai-ji moved all of the objects to the upper level during renovations and ordered illustrations prepared for some of the artifacts. The original illustrated manuscript no longer exists, but several copies were made and circulated under the name illustrations of Shōsō-in Imperial Treasures (Shōsōin gohōmotsu zu 正倉院御寶物之圖) through the Edo period (1603–1868). In most cases the first illustration in the book depicts the ranjatai, such as we find in a copy held by Kyoto University (below).

Five years before Emperor Meiji took a small piece of the famed aloeswood, survey teams were sent out around Japan to record objects and artifacts that had historical and cultural importance. Some of the items in the Shōsō-in were photographed over the course of twelve days in the summer of 1872, including the ranjatai. Looking closely at the photograph taken during that survey (below) we can see a small rectangular section had previously been cut away on the hollowed-out end. In comparison to the modern photo above, we can also see where Emperor Meiji would soon cut off a 8.9 gram piece from the narrower end. The Meiji-era label confirms this was the case.

It was not until after World War II that modern scientific studies were undertaken on various artifacts from the imperial treasury, in part for material identification, but also for the sake of preservation. Wada Gun’ichi 和田軍一 (b. 1896–?), director of the Shōsō-in, was among the first in charge for overseeing these matters and he took a special interest in the famous aloeswood piece. After scouring numerous Shōsō-in documents he found no evidence supporting the ranjatai’s presumed benefaction in the eighth century. The oldest document possibly bearing witness to the aloeswood comes only in 1193 (Kenkyū 4), where it might appear under the name ōjukukō 黄熟香.

This corresponds in part to what we know about the history and evolution of kōdō 香道, “the way of incense,” in Japan. It was only during the Muromachi period (1336-1573) that distinctive names were given to famous pieces of aromatics; this did not yet occur in the eighth century. We have evidence of this naming practice growing through the Edo period until a list of sixty-one different “famous aromatics” was developed under the auspices of perfume and incense aficionados (although different enumerations exist). As a sign of prestige, it is typical for kōdō practitioners to place Tōdai-ji’s ranjatai at the head of such listings.

Nevertheless, it remains unknown who donated the ranjatai or when it arrived at the Shōsō-in, although scholars have offered several different speculations. Moreover, precisely when the fragrant wood received its “honorific name” of ranjatai is also in dispute.

The Shōsō-in continues to officially catalogue the famous artifact under ōjukukō despite the widespread use of ranjatai in popular media. This former name can be seen, for example, in the copy of the 1693 illustrated shown above. Ranjatai, in smaller calligraphy, is listed as an “alternate name.” Ōkukukō is also written on the lid of the storage crate (below) were the famous piece of aloeswood is kept. It is believed this crate was also made in 1693 when the imperial treasures were inspected.

More recently, Yoneda Keisuke 米田該典 has performed a scientific analysis on the ranjatai to determine its botanical and graphic origins. Based on its chemical composition and comparison to chemical signatures of collected aloeswood samples, Yoneda concluded the Shōsō-in specimen originated from Aquilaria trees in Vietnam or Laos. This is a region closely associated with fine quality aloeswood since the third century in China.

Since 1946 various items from the Shōsō-in treasury are put on display each fall in the ancient capital of Nara. Many items are only available to be viewed by the public during these annual exhibitions. During the second exhibition in 1947 the ranjatai was selected for display. It was not displayed again until 1982, then again in 1997 and 2011. It was most recently displayed during the 72nd Annual Shōsō-in Exhibition in 2020. In addition, when Emperor Hirohito was enthroned in 2019, the ranjatai was put on special display in Tokyo for the occasion.

Like a scared relic only viewable to the few, these events further deepen the allure of the ranjatai, adding more layers to its already complex mythos.

External Links & Image Sources

- Ōjukukō (Ranjantai) in the Illustrations of Shōsō-in Imperial Treasures (Shōsōin gohōmotsu zu 正倉院御寶物之圖) held by Kyoto University [here]

- Ōjukukō (Ranjantai) at Shōsō-in’s Digital Repository [here]

- Ranjatai photograph from 1872 Jinshi Survey of cultural assets [here]

Selected References

- Hamasaki Kanako 濱崎加奈子. 2017. Kōdō no bigaku: Sono seiritsu to ōken renga 香道の美学: その成立と王権・連歌. Kyoto: Shibunkaku shippan 思文閣出版.

- Īda Takehiko 飯田剛彦 and Sasada Yū 佐々田悠. 2021. “Shōsōin Hitsu-Rui Meibun Shūsei (Ni): Keichō Hitsu Genroku Hitsu 正倉院櫃類銘文集成(二): 慶長櫃・元禄櫃.” Shōsō‑in kiyō 正倉院紀要 43: 33–61.

- Wada Gun’ichi 和田軍一. 1976. “Ranjatai らんじゃたい.” Nihon rekishi 日本歴史 335: 40–43.

- Yoneda Keisuke 米田該典. 2000. “Zensenkō Ōjukukō no kagaku chōsa 全淺香、黄熟香の科学調査.” Shōsō‑in kiyō 正倉院紀要 22: 29–40.

For further information and additional references, see: Peter M. Romaskiewicz, “Sacred Smells and Strange Scents: Olfactory Imagination in Medieval Chinese Religions.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2022.