Introduction

Frankincense and myrrh were two kinds of incense gifted to the baby Jesus according to the New Testament story of the Magi. Considering gold constituted the third gift, we can surmise how important such aromatics were to people in the ancient Mediterranean. Frankincense is an oleogum-resin with a distinctive balsamic-citrus scent that is produced by several species of the Boswellia tree. Biblical incense is thought to have traversed the two-to-three-month long trip along the so-called Incense Route connecting the eastern Mediterranean to the southern Arabian peninsula were Boswellia naturally occur. The subtropical-tropical climate of this region allows for the growth of many different kinds of fragrant resin-producing tress. There is also an Indian frankincense produced by the native Boswellia serrata, but this does not seem to have significantly impacted classical Greco-Roman commerce. It might be the case, however, that Indian frankincense, or a mixture of Arabian and Indian frankincense, was brought into China by at least the mid-third century. The origin for the early Chinese name for frankincense, xunlu xiang, is contested by scholars, with some claiming it is a transcription of the Sanskrit kundurūka and others claiming it is a hybrid or fully Chinese name. By the eighth century a new name for frankincense becomes dominant, Milky Aromatic (ru xiang 乳香), reflecting the Arabic name for frankincense, luban, “milky, white,” and the growing commercial importance of the Arabic sea trade.

Facts and Features

- Medieval Chinese Name: Xunlu Aromatic (xunlu xiang 薫陸香), Milky Aromatic (ru xiang 乳香)(additional names for different commercial grades)

- Common English Name: frankincense, olibanum

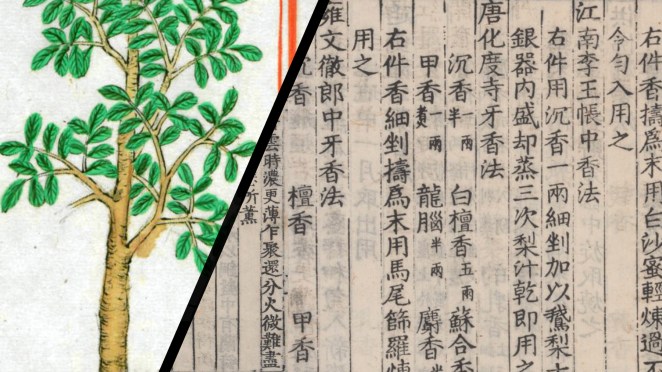

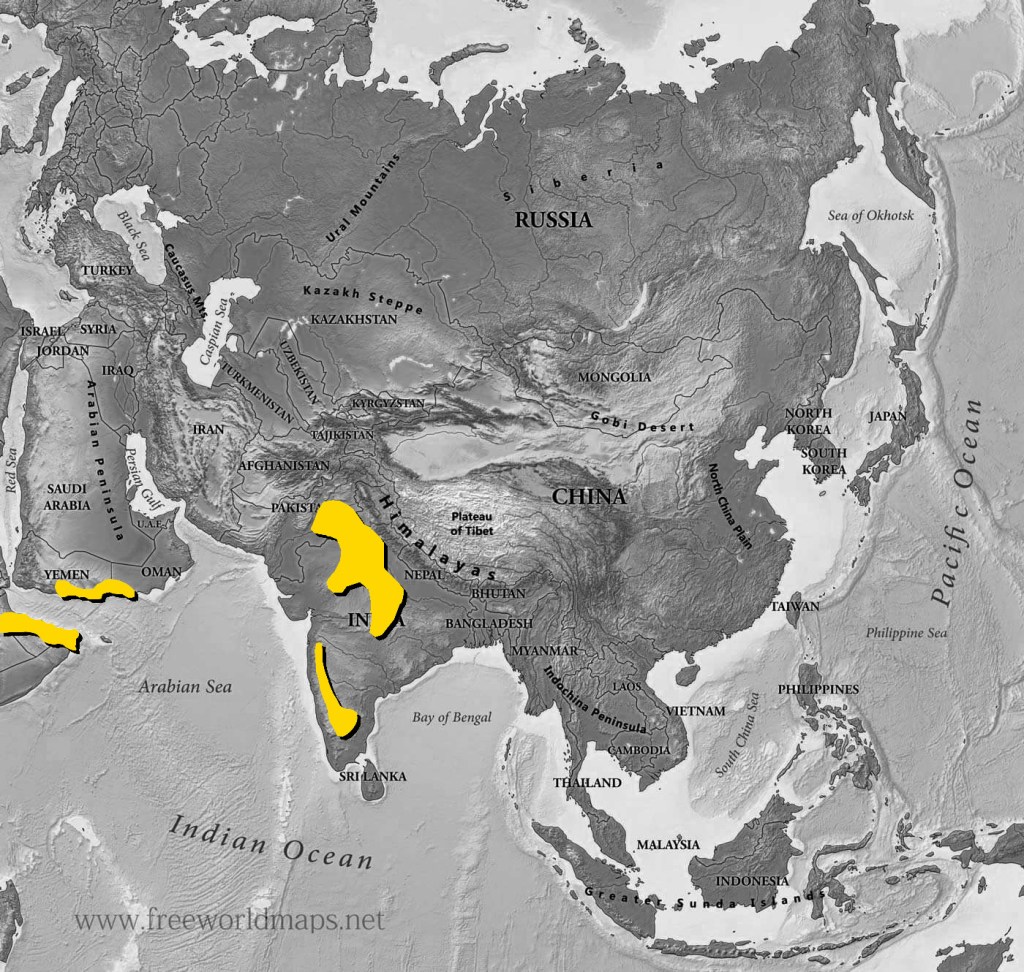

- Botanical Origin: oleogum resin extracted from several species of the Boswellia tree (esp. B. sacra, B. frereana, B. papyrifera, B. serrata)

- Phytogeographic Distribution: Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia on the Horn of Africa, southern Arabian Peninsula, northwestern and southern India [approximate distribution* of frankincense is shown in golden yellow below]

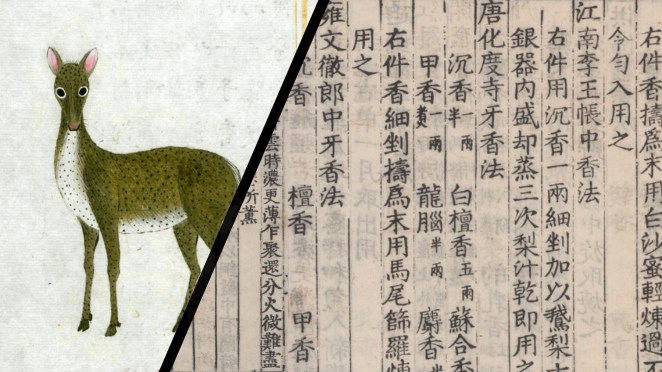

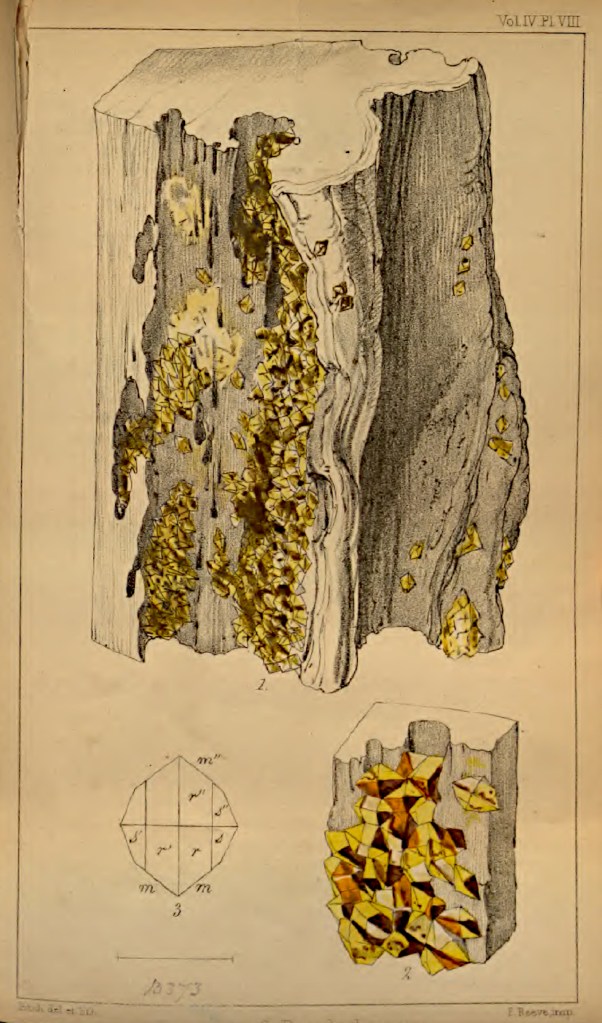

- Harvesting Process: the bark of the tree is notched or slashed causing the release of milky oleogum resin that thickens upon contact with the air, then the globule pear-shaped tears can be collected

- Earliest Chinese Citation: mid-3rd century CE (e.g. dynastic history: Abridged Account of Wei [Weilüe 魏略]) & late 3rd century (translated Buddhist sutras)

- Earliest Chinese Medicinal Use: 3rd/4th– late 5th century (Supplementary Record by Famous Physicians [Mingyi bielu 名醫別錄] and Collected Annotations on the Classic of Materia Medica of the Divine Husbandman [Shennong bencao jing jizhu 神農本草集注])

Comments: Frankincense first appears in extant Chinese sources in mid-third century when it appears alongside several other aromatic imports from the Roman Empire, including storax, saffron, and possibly rosemary. For the early medieval Chinese, frankincense was considered an export of the Roman Empire, but in reality the Romans were only transshipping the resin into India where it would have been sent onward to Chinese merchants via Central Asian middlemen. By the mid-seventh century frankincense was considered a direct export of India, possibly indicating the circulation of the Indian variety. By the late medieval period, frankincense was strongly connected to Arab trade and in such cases was sourced from the southern Arabian peninsula.

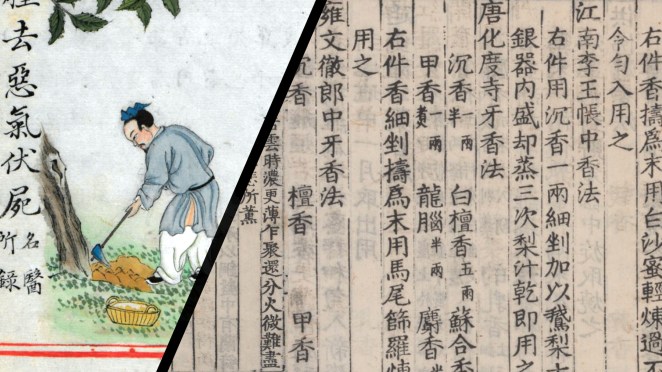

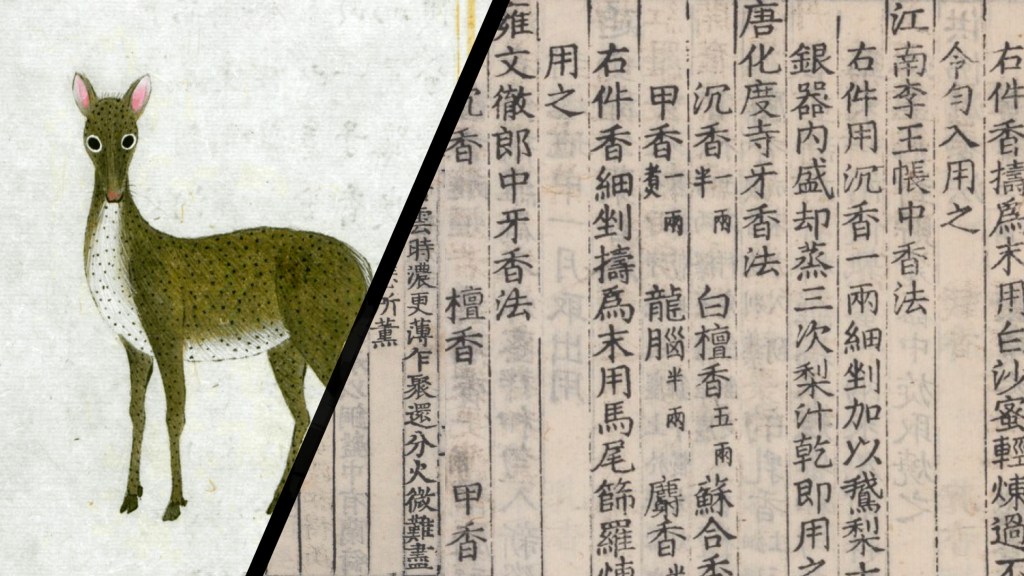

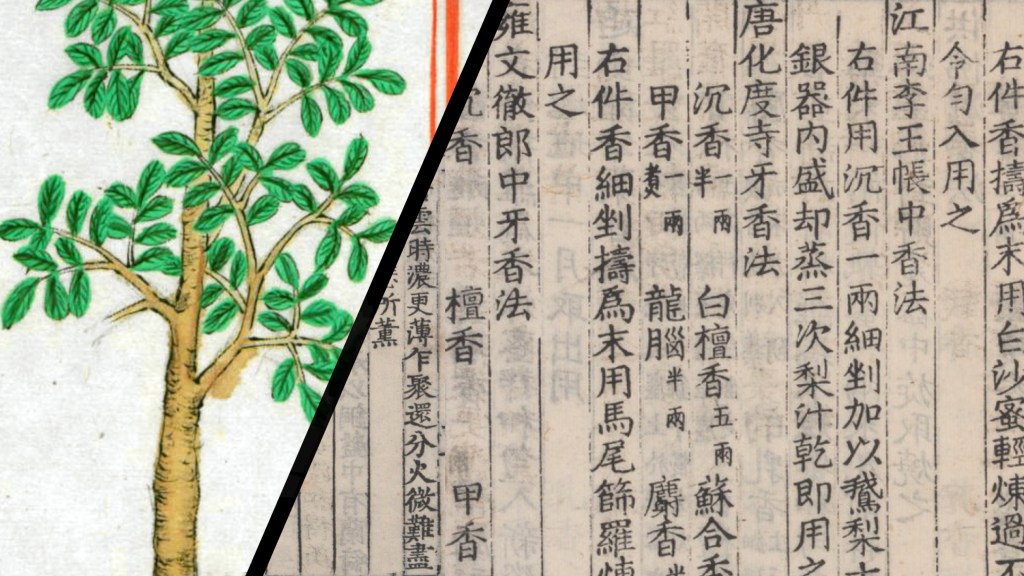

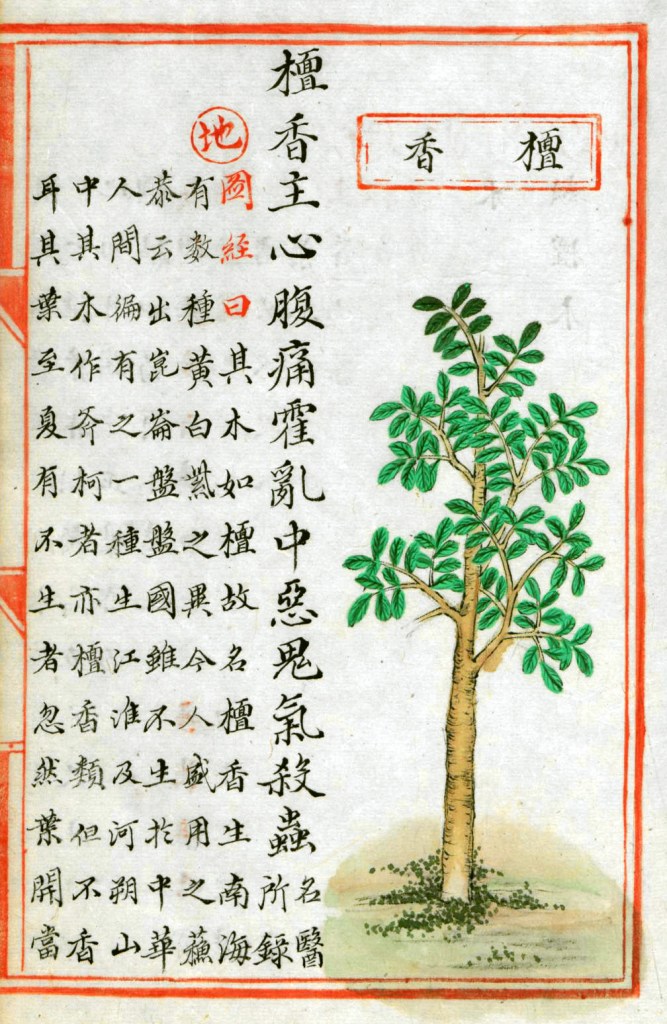

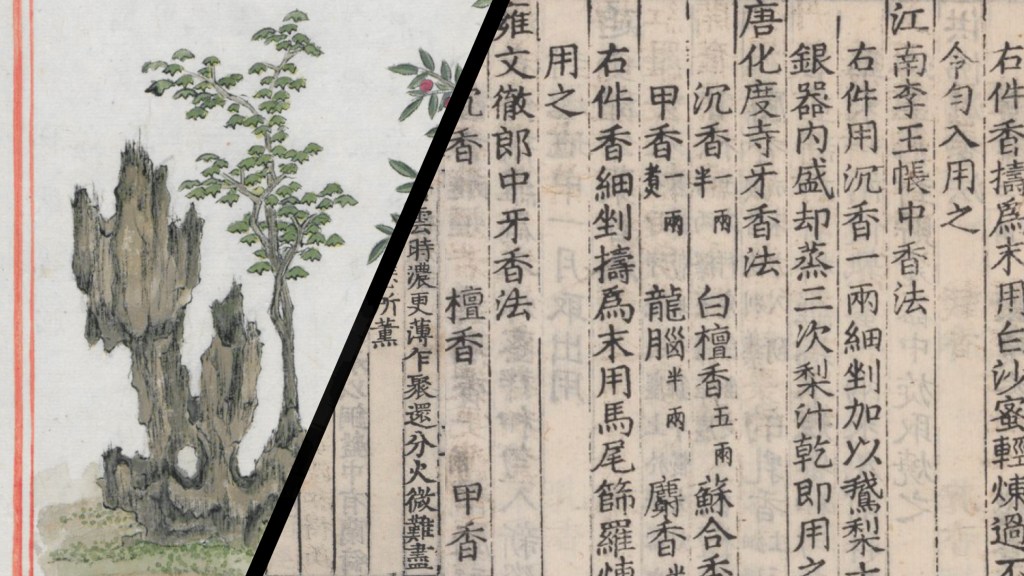

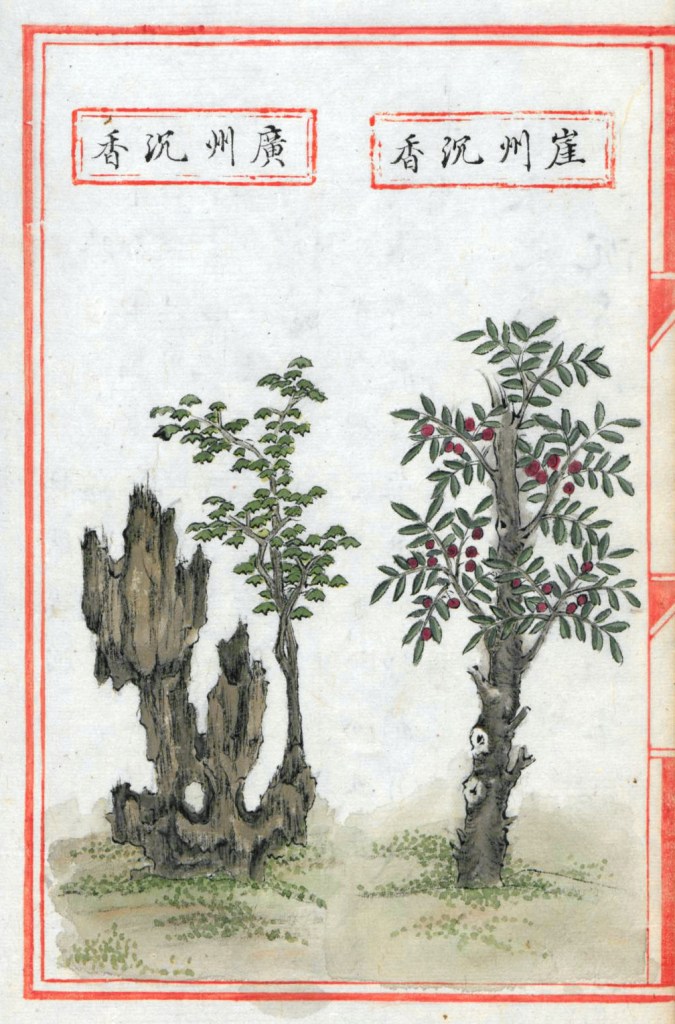

If we examine the Classified Essentials of Materia Medica (Bencao pinhui jingyao 本草品彙精要) from 1503 we find a pair of illustrations for the frankincense tree, one showing Xunlu Aromatic (on the left), the other showing Milky Aromatic (on the right). While the later shows clumps of resin forming on the bark (in uncharacteristic lime green), the former unexpectedly shows a collector digging into the ground around the base of the tree. Presumably, this was necessary when frankincense resin dripped from the bark wound on to the ground. The golden resin can be seen in the collection basket.

It is often claimed frankincense was used in pharaonic Egypt, but precise dating for its importation into Upper Egypt remains unclear. For example, there is a famous series of reliefs in the temple at Deir al-Bahri near Thebes which describe an expedition sent around 1500 BCE by Hatshepsut (r. 1481–1472 BCE) that crossed land and sea. The expedition to the unidentified land known as Punt returned with live trees preserved in pots as depicted in the reliefs. Moreover, it is noted the trees were used as fragrant ointment. Scholarly discussions over the depictions and associated terminology have not determined if these trees were Boswellia or a type of myrrh tree (or something else). Regardless of the famed Punt expedition, evidence suggests the Incense Route from southern Arabia commenced around the end of the eighth century BCE, supported by massive camel caravans. Herodotus speaks of Arabian frankincense in the mid-fifth century BCE as does Theophrastus in the third century BCE. The first century Periplus Maris Erythraei gives detailed accounts of both Arabian and Somali frankincense and notes that the fragrant resin is delivered into Indian ports. The history of frankincense in India, either imported or indigenous, is hampered by issues of terminology. Kunduru/kundurūka, śallakī/sallakī, and turuṣka are all treated as possible words for frankincense, among others. If we look towards the surviving Chinese translations of Indic Buddhist scriptures, we find the use of Xunlu Aromatic to translate (presumably) kundurūka at the end of the third century.

* The map is intended as a general heuristic for distribution and range, it ireflects selected data from modern scientific research and descriptions from medieval Chinese materia medica and gazetteers

For further information and additional references, see: Peter M. Romaskiewicz, “Sacred Smells and Strange Scents: Olfactory Imagination in Medieval Chinese Religions.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2022.