Introduction

My first few attempts at teaching university courses in Religious Studies did not take the learning outcomes [LOs] too seriously.[1] They were window dressings, a convention of the syllabus genre that had very little purpose. Today, LOs significantly shape the courses I create, indeed, they are a foundation. This is my conversion story and a template for crating your course LOs.

Thinking Backwards

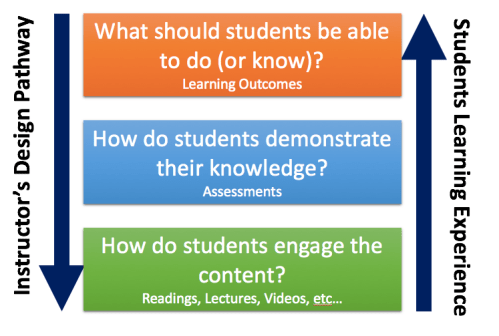

Of course, those familiar with “backwards design” (from the Understanding by Design framework) know the entire process of designing a new class begins with drafting LOs. LOs are the skills, habits, and patterns of thinking that students will cultivate in your course. It is worth noting that LOs have minimal overlap with “content.” In other words, these define what the students will do with the content.

This is very different from the practices I absorbed as a graduate student. In fact, for folks like me who started designing courses by selecting readings first this approach may seem, well, “backwards.” The name “backwards design” reflects this.

It also represents the opposite direction from the perspective of the student in the course. If the student’s learning experience builds upwards from readings and lectures, the instructors pathway for course design should start with LOs and scaffold to meet those goals.

Why Think Backwards? A Conversion Story

Thinking “backwards” allows us to focus on what matters, to not lose the forest for the trees. Our courses should – or at least can – enhance how students think, not merely augment the facts they know.

When we just focus on our lecture material or the content of readings, it is easy to forget these larger aspirations. We should not only be concerned with our students learning facts, but what they can do with those facts.[2] This may seem inescapable for some disciples, but bewildering for others. For example, no math instructor would simply expect students to memorize formula, they’d expect students to know how to apply those formula in increasingly more complex scenarios.

To use myself as the sacrificial counter example, what do I want students in my Religious Studies course to do? I used to think that once I figured out the readings, what the students did was obvious: write a paper! But a writing assignment should be viewed as an assessment of meeting the LOs, not an outcome in itself (refer to chart above).

Like many novice instructors, even when I had these grand aspirations the stress of putting together a new syllabus often pulled me back to the “basics” – the basics of deciding reading material and crafting lecture notes. As I was recently telling several new instructors, I did not appreciate the power of LOs because I was struggling day-to-day. I had long given up on the big picture. In my experience, even after the first time I designed a course starting from the LOs, I was unconvinced by their ultimate value.

After I built up some confidence teaching – specifically getting my “reps” in teaching freshman writing, an explicitly skill-based course – and learning I could survive day-to-day, I became dissatisfied with my assessments in my other Religious Studies courses. Uninspired quizzes, midterms, finals, and papers were the rigmarole. I soon started to think the problem was how I was conceiving of my courses’ role in the lives of my students. Did I just want them to memorize facts and become trivia masters?

By continually placing my focus on texts I consequently funneled my assessment onto low-level tasks of comprehension and memorization. Inspired to try and have my students train in higher-level orders of thinking, most specifically in analysis and evaluation, I first changed my daily reading assignments. Instead of having students summarize the main argument, I asked them about their opinions (gasp!). Specifically I asked them which passages struck them as interesting and why, which passages were confusing and why, which passages were they critical of and why. In other words, I started to think “backwards.” My students were now directly practicing – sometimes imperfectly[3] – the skills I wanted them to develop.

Class conversation immediately perked up. This was a small revelation. My thinking process then filtered up into the types of essay prompts I devised. Now, all of my assessments are derived from my LOs. My lectures are – and I only mean this in a relative sense – irrelevant (shun me if you must). Don’t get me wrong, I love planning a good lecture, but I now fully envision lectures in service of LOs.

In my retelling, the crux of my conversion story falls upon trying to re-conceive my assessment strategies. Now, when I think about readings, I also have to consider their capacity to help me reach the objectives I have set for my students. Sometimes, this forces me to “create” a lot more (like podcasts), but in return I also ask students to “create” a lot more – I consider this a win-win.

So…What Does a LO Look Like?

There are many many many introductions to crafting Learning Outcomes online, here are my crib notes:

Well-written Learning Outcomes will:

- Tell the student what they will do (not what the teacher will do).

- Use “thinking” action verbs that help measure the level of learning (see Bloom’s taxonomy for ideas)

- Refer to specific content (and/or clearly telescope to particular assessments, i.e. are measurable)

- Are concise and clear

Generally, a LO will often take the form: Actor/student + Bloom’s taxonomy verb + topic/content/related activity/assignment.

Also, it is advisable to erase the following verbs and phrases from LOs: learn, know, understand, appreciate, be aware of, and be familiar with.

I’ll admit, these are often the terms we instructors think with when we causally reflect on our classes. But these actions cannot be measured in an activity, assignment, or exam.

Notes

[1] I don’t want to get too far into the weeds, but there is a distinction between “learning outcomes” and “learning objectives.” In my run down, objectives refer to the content of the course or goals of an activity (think: list X, discuss Y, state Z), while outcomes reflect what the student will do to achieve that objective (think: analyze, evaluate, create). The latter, being more directly student-oriented, are often included in course syllabuses. In practice, however, these terms are often interchangeable. Specific differences in objective and outcomes are discussed here.

[2] There are clear disciplinary differences here. From my many consultations with instructors and teaching assistants from across disciplines, skills are more at the forefront of STEM (think: how can I apply this formula to this problem). Unfortunately, folks in the humanities (students and instructors) too-often think memorization of content is the apex of learning.

[3] This point is often overlooked. For the most part, students have been trained to summarize – this is the easiest thing to test on standardized tests. Thinking with the text is a new skill, please do not think students will all be masters at this skill immediately, it needs to be modeled, practiced, failed, and retried.

Pedagogy Workshops