For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

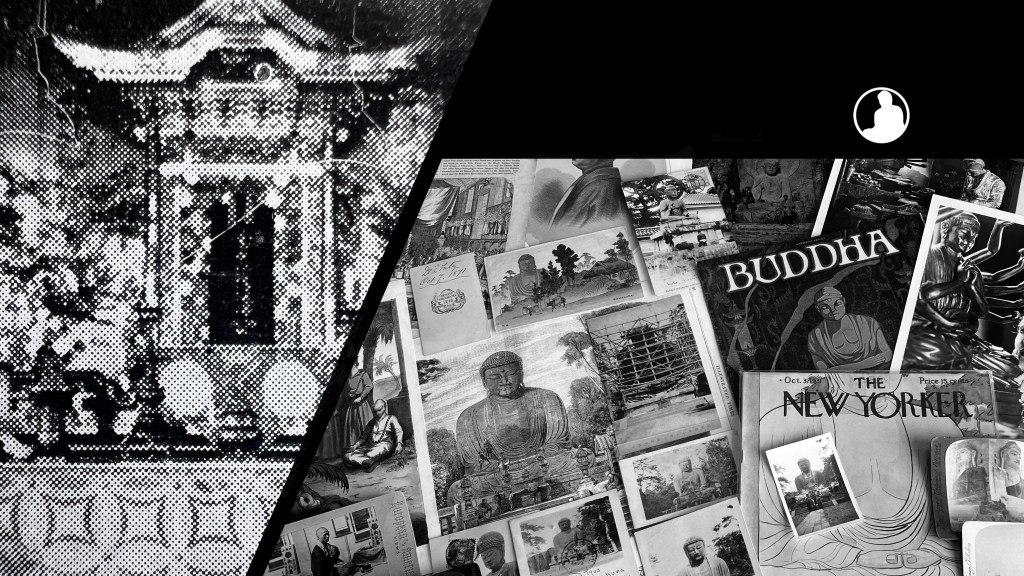

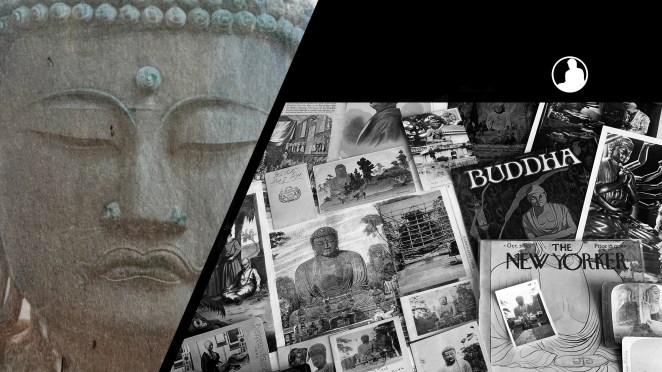

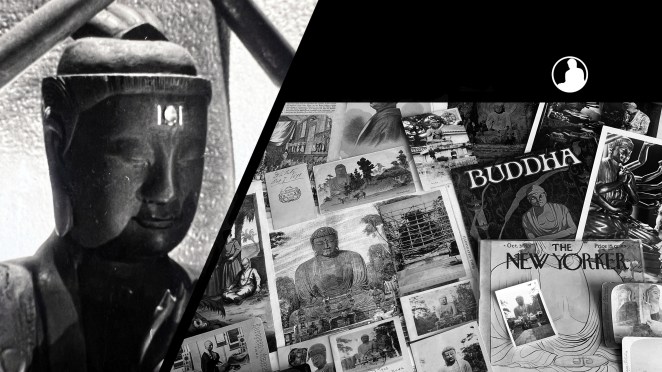

Inspired by the success in San Jose and Sacramento, Izumida Junjō 泉田準城 (1866–1951) arrived in Los Angeles in 1904 and opened the city’s first Buddhist temple for Japanese immigrants. After raising funds and purchasing land, a newer and larger temple was opened in 1911 on Savannah Street.

Associated with Nishi Hongan-ji, a Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist organization headquartered in Kyoto, Izumida organized the Rafu Bukkyō-kai 羅府仏教会, the Buddhist Mission of Los Angeles. It was meant to meet Japanese immigrants’ needs for funerals, memorial services, and spiritual guidance.

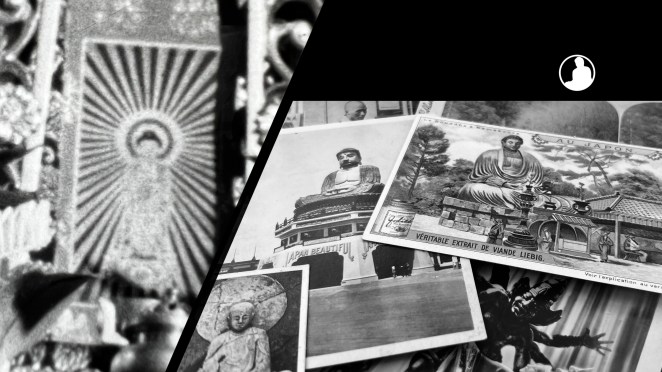

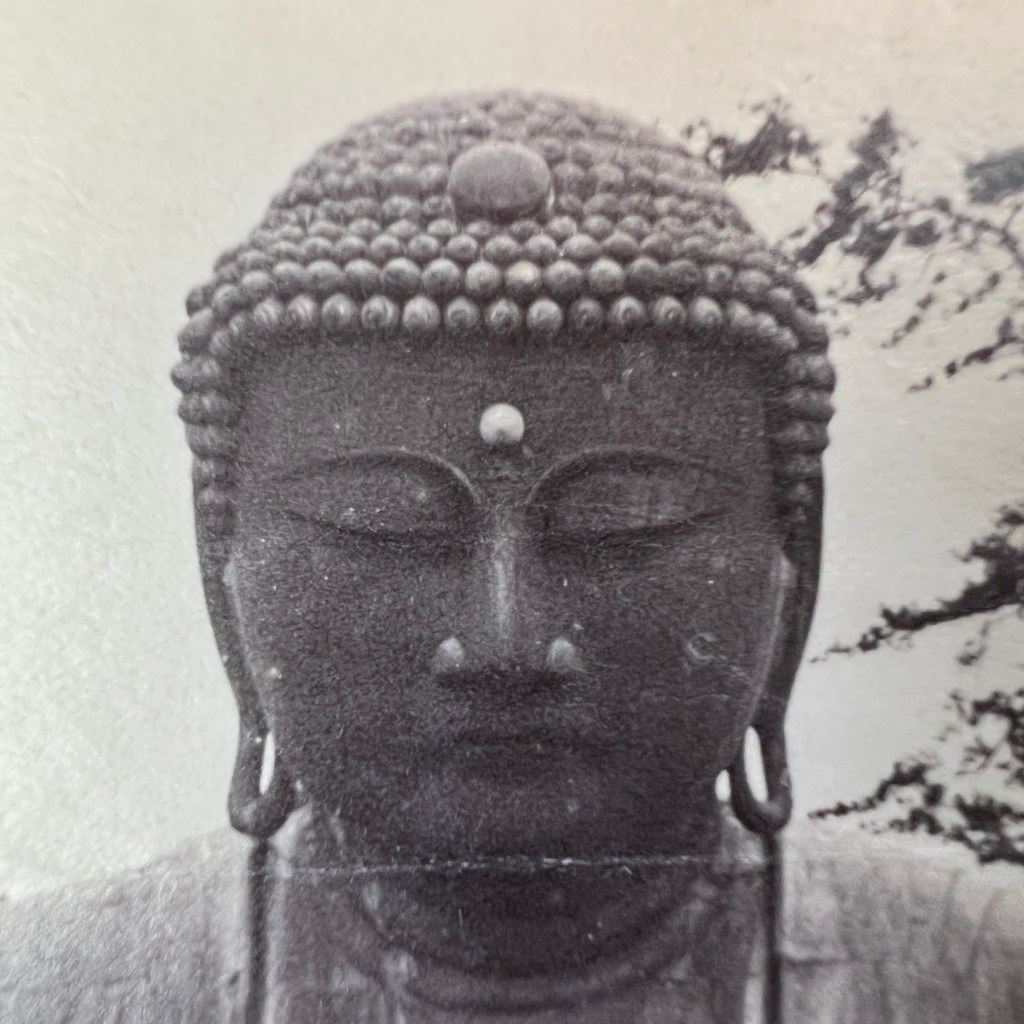

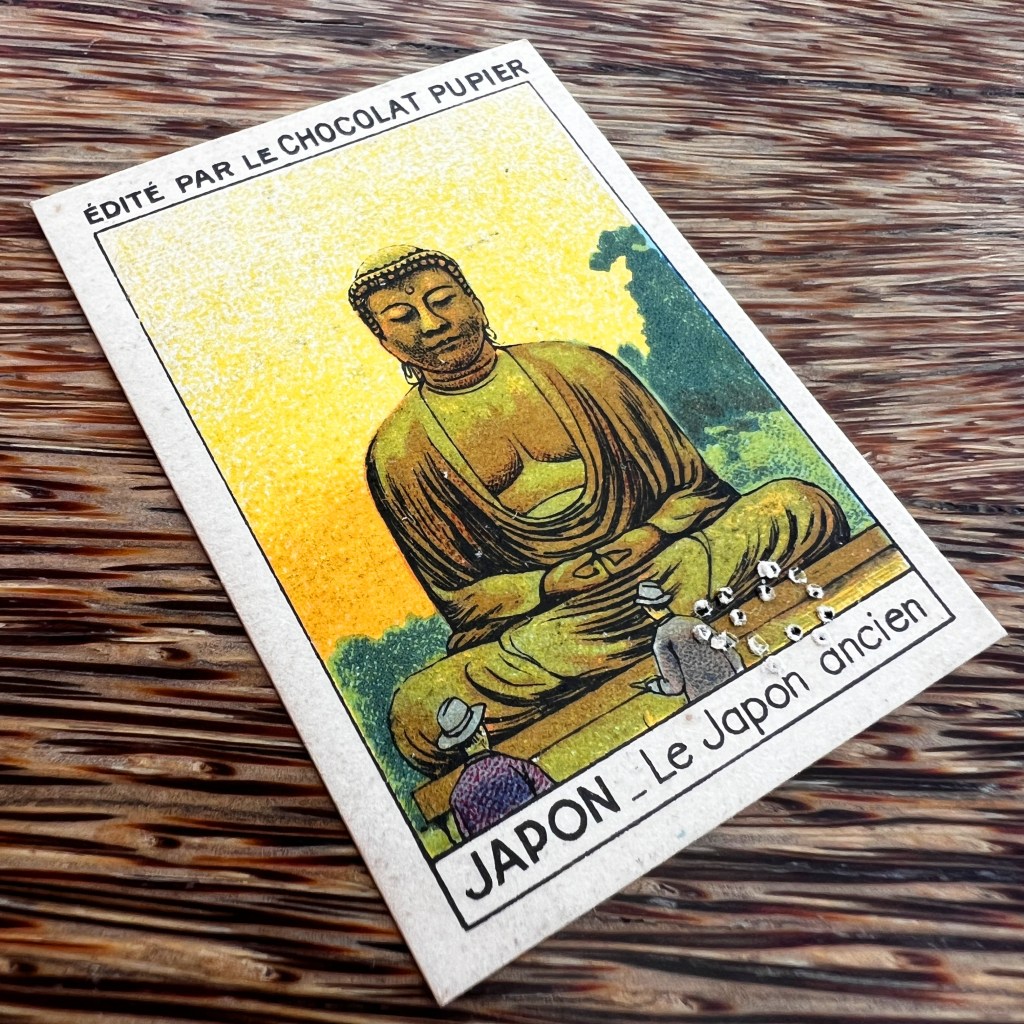

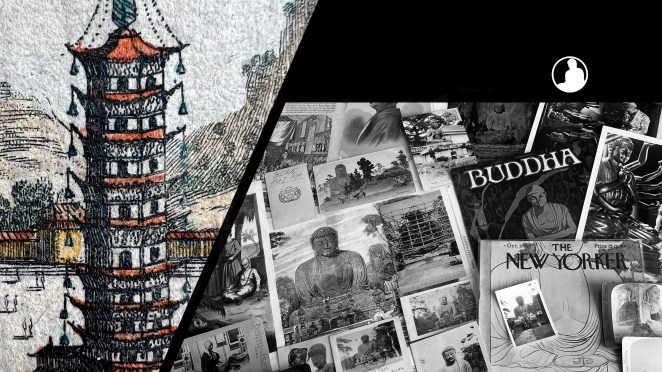

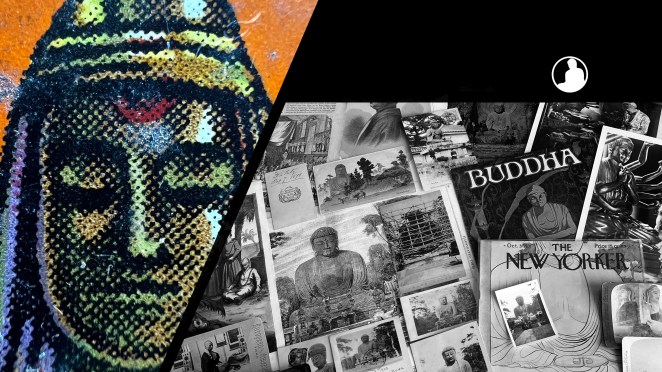

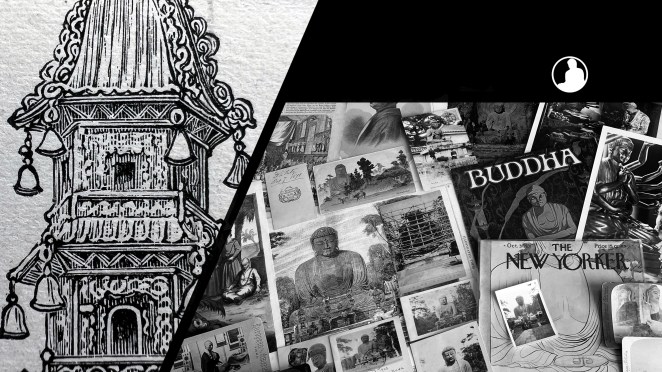

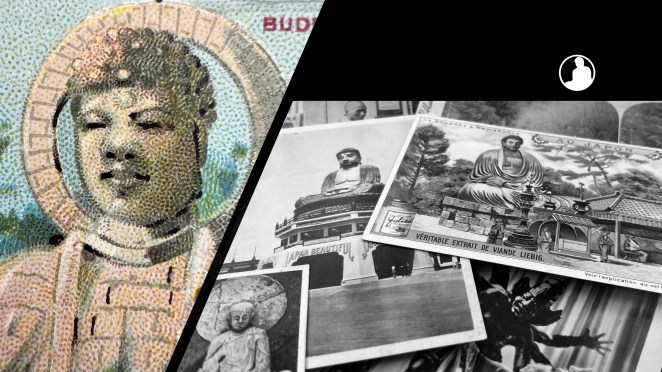

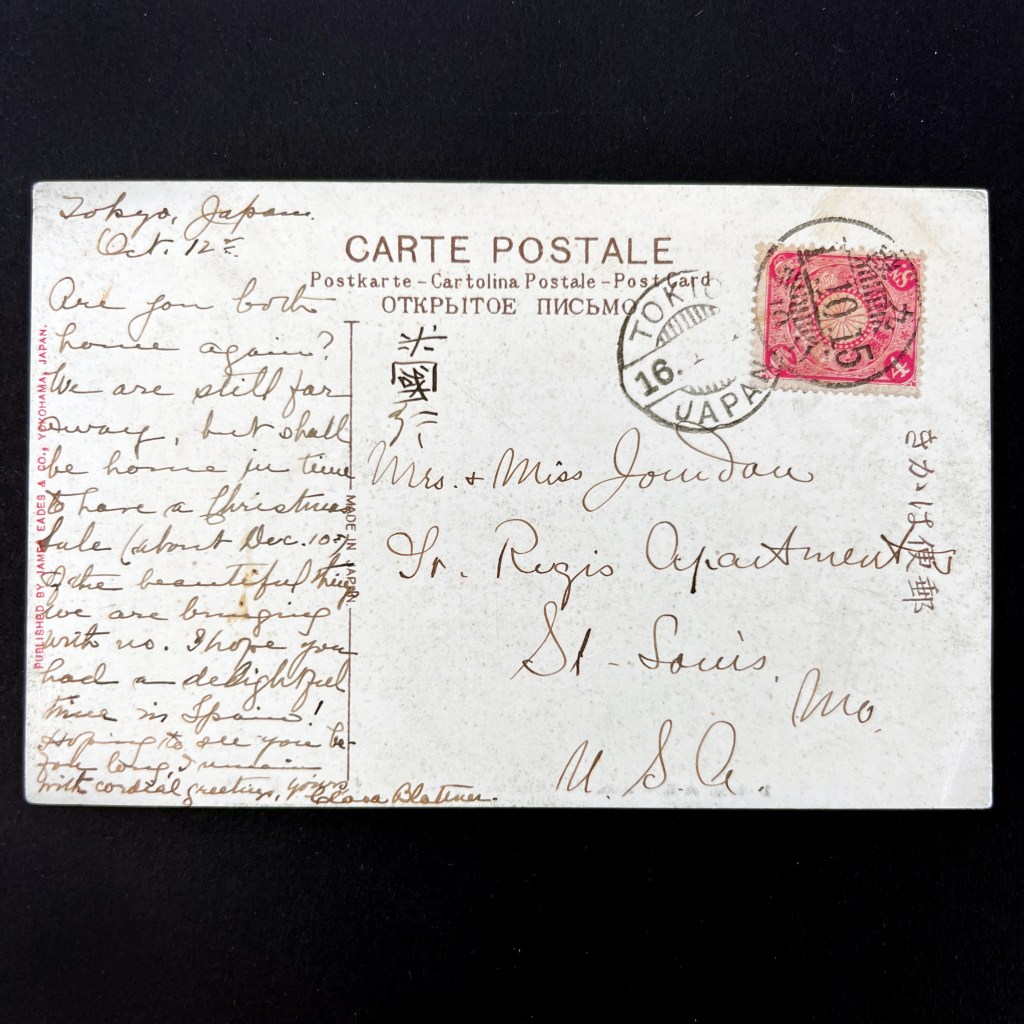

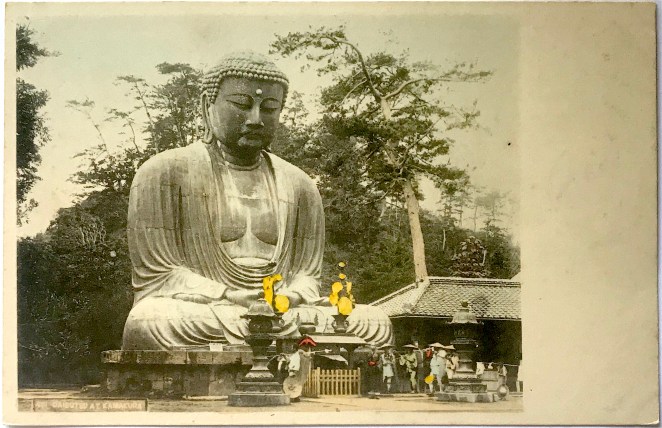

Possibly in celebration and promotion of the new temple, the Mission issued picture postcards highlighting both the interior and exterior of the building. The colorful illustrated elements on the front reveal an Arts and Crafts influence popular in the early 20th century.

The building was meant to reflect both American residential architecture and Japanese temple architecture. The latter can be seen in the curved eaves on the roof and the temple-style gate over the front porch.

The interior also shows a hybrid style, with church-like pews set in front of a traditional Japanese Buddhist altar.

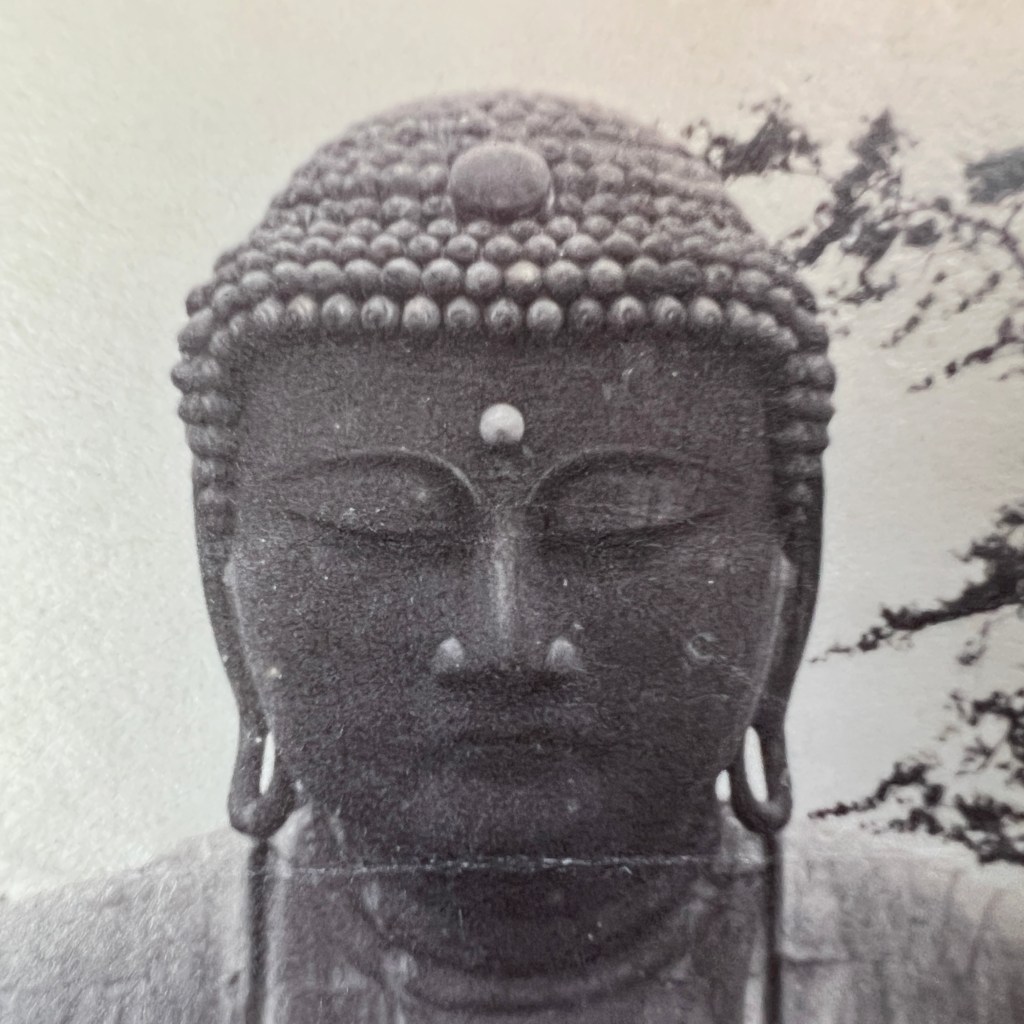

As a Jōdo Shinshū temple, the shrine is dedicated to Amida Buddha, here with a scroll bearing his name. For more on the history of this LA temple, see Michihiro Ama, Immigrants to the Pure Land: The Modernization, Acculturation, and Globalization of Shin Buddhism (2011).

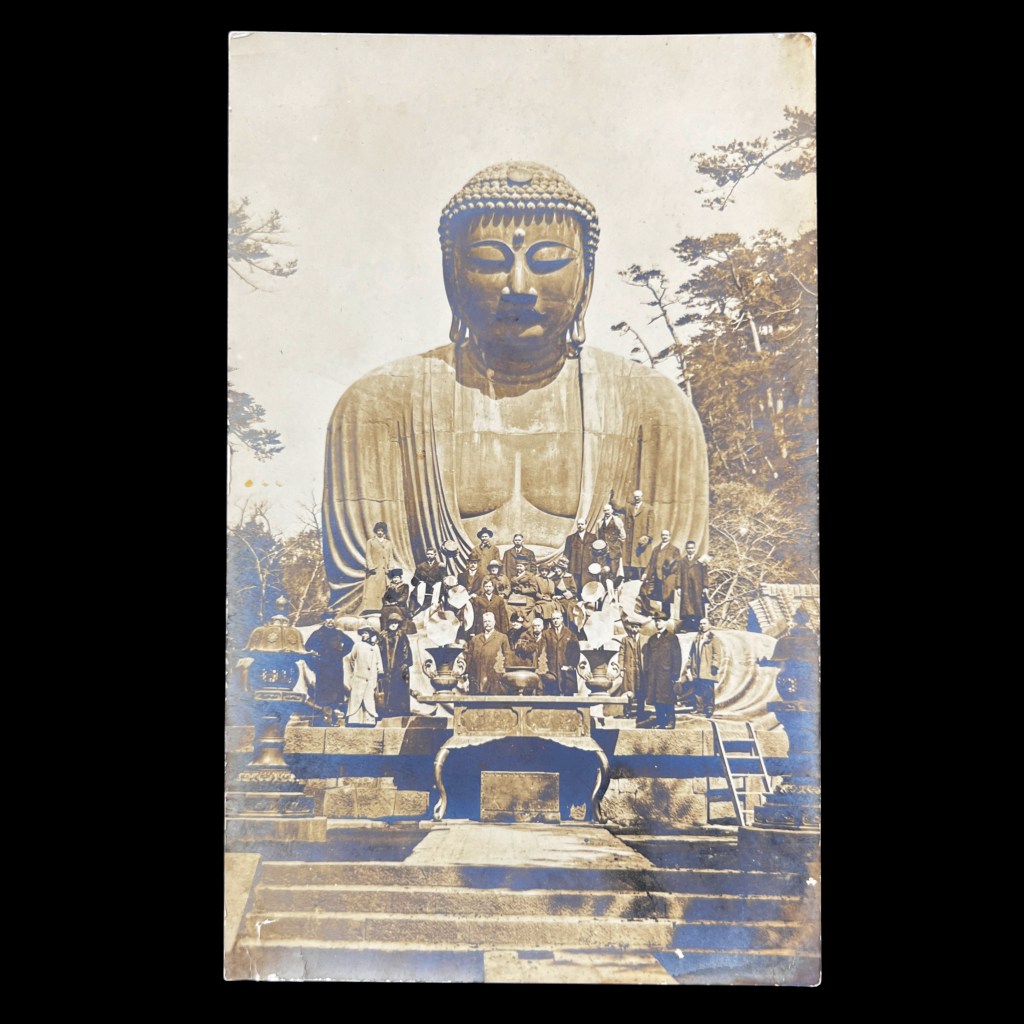

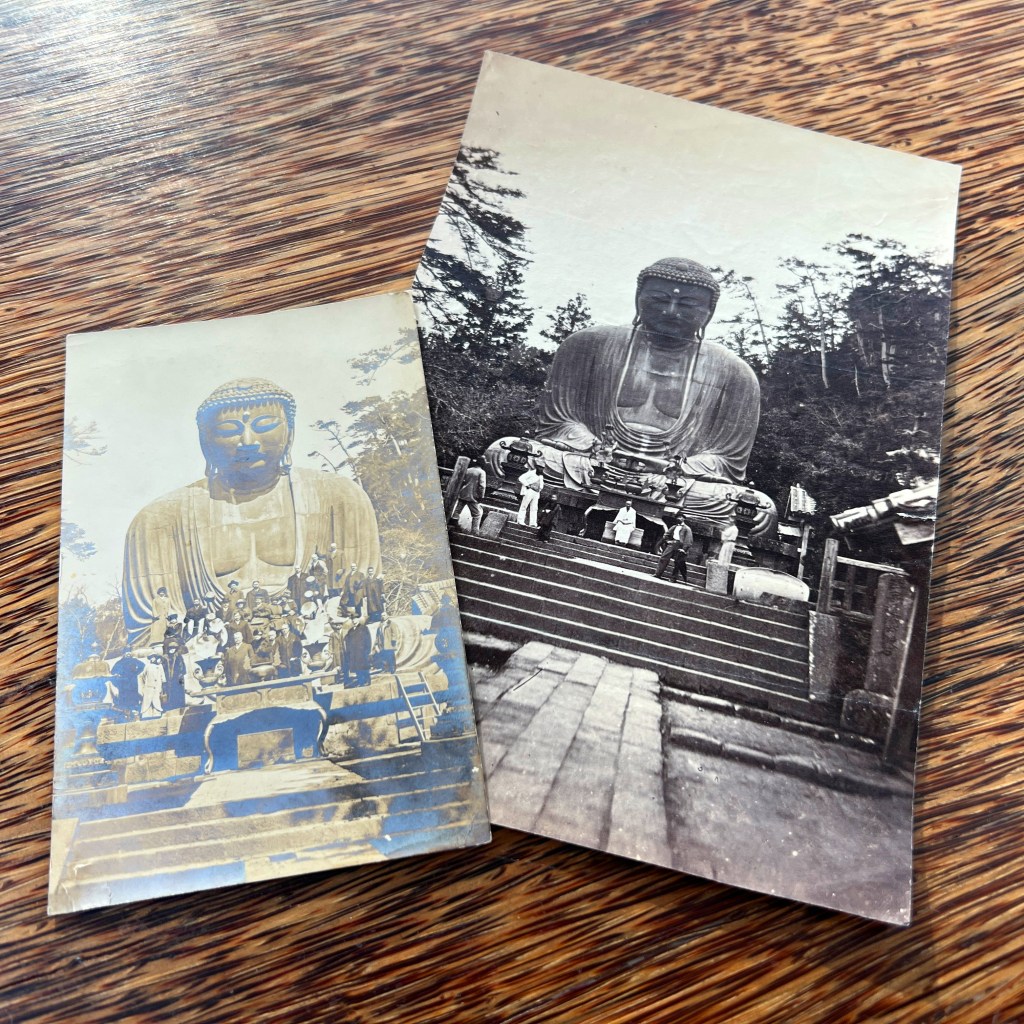

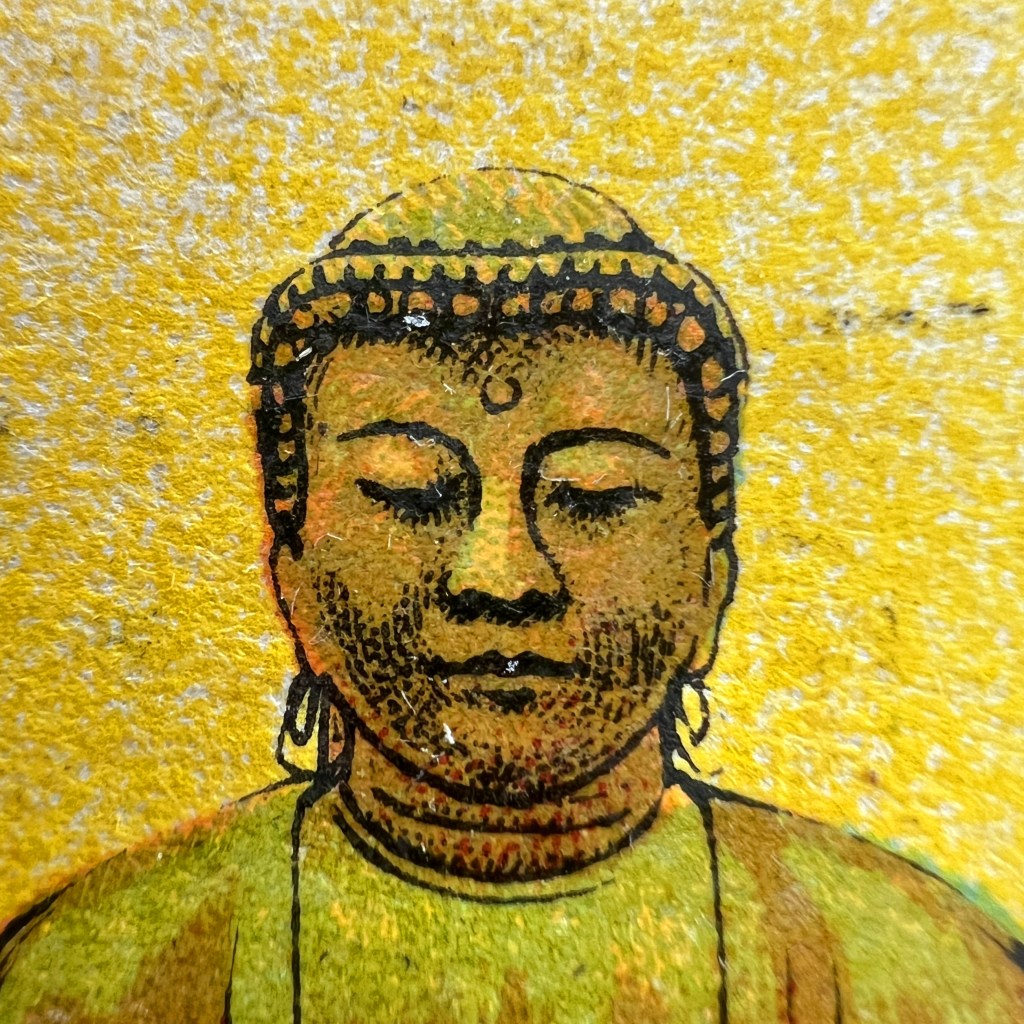

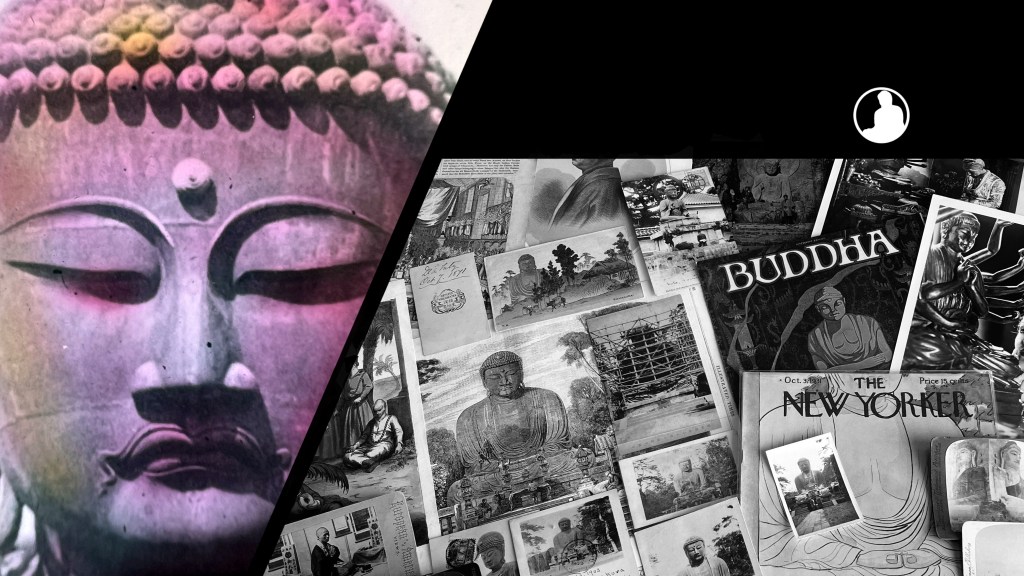

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Historical Trade Cards:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: