For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

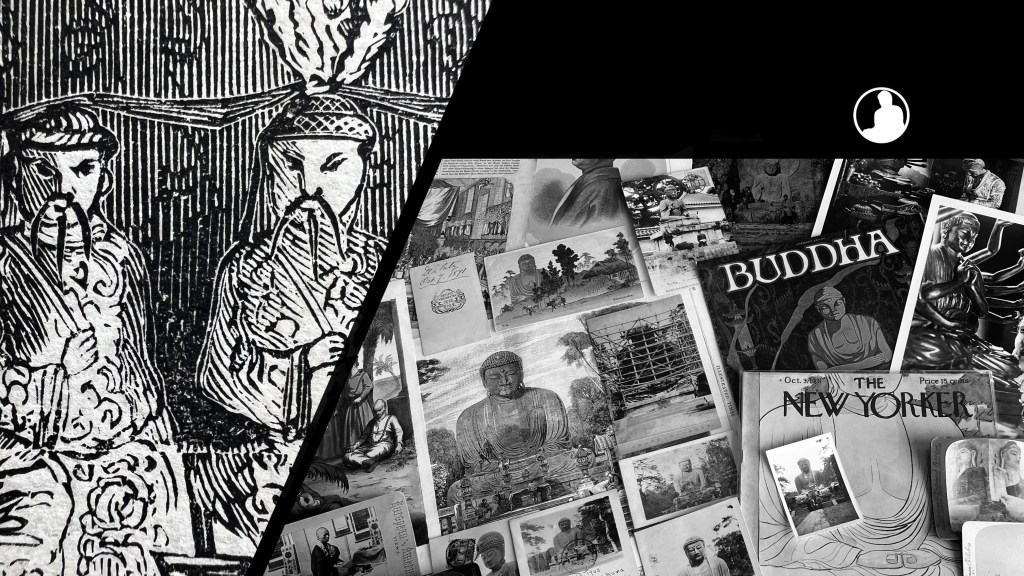

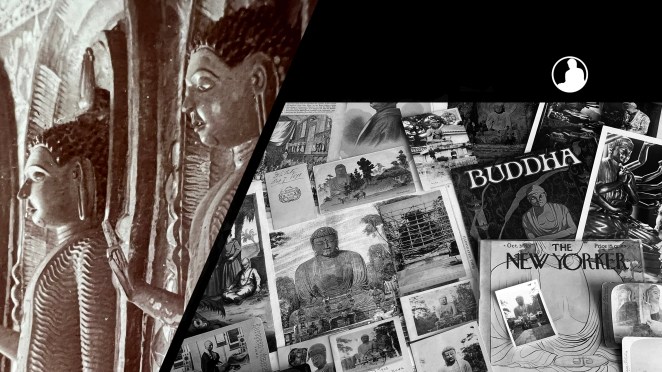

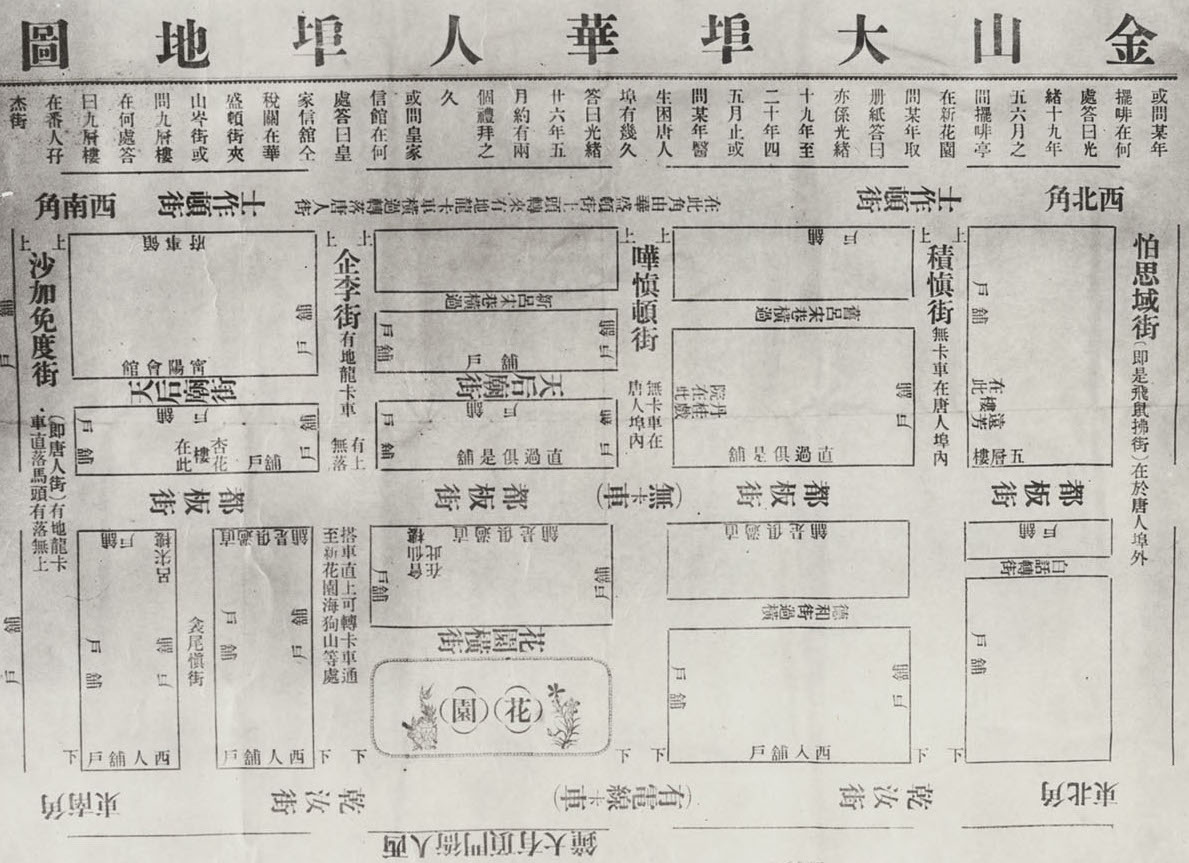

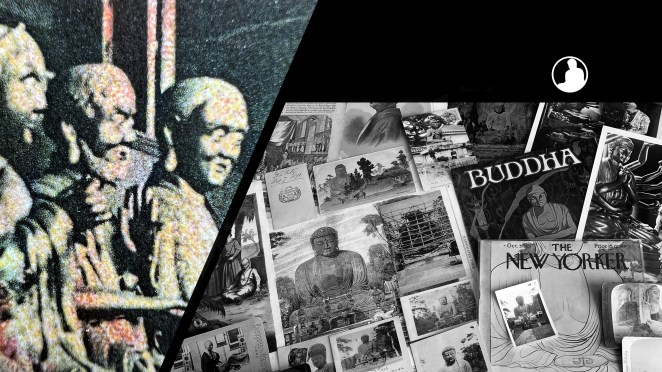

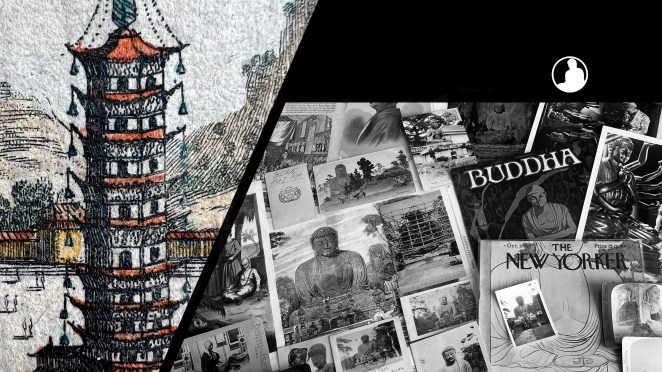

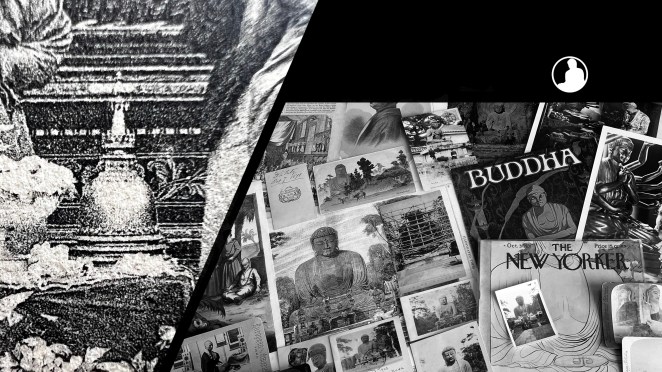

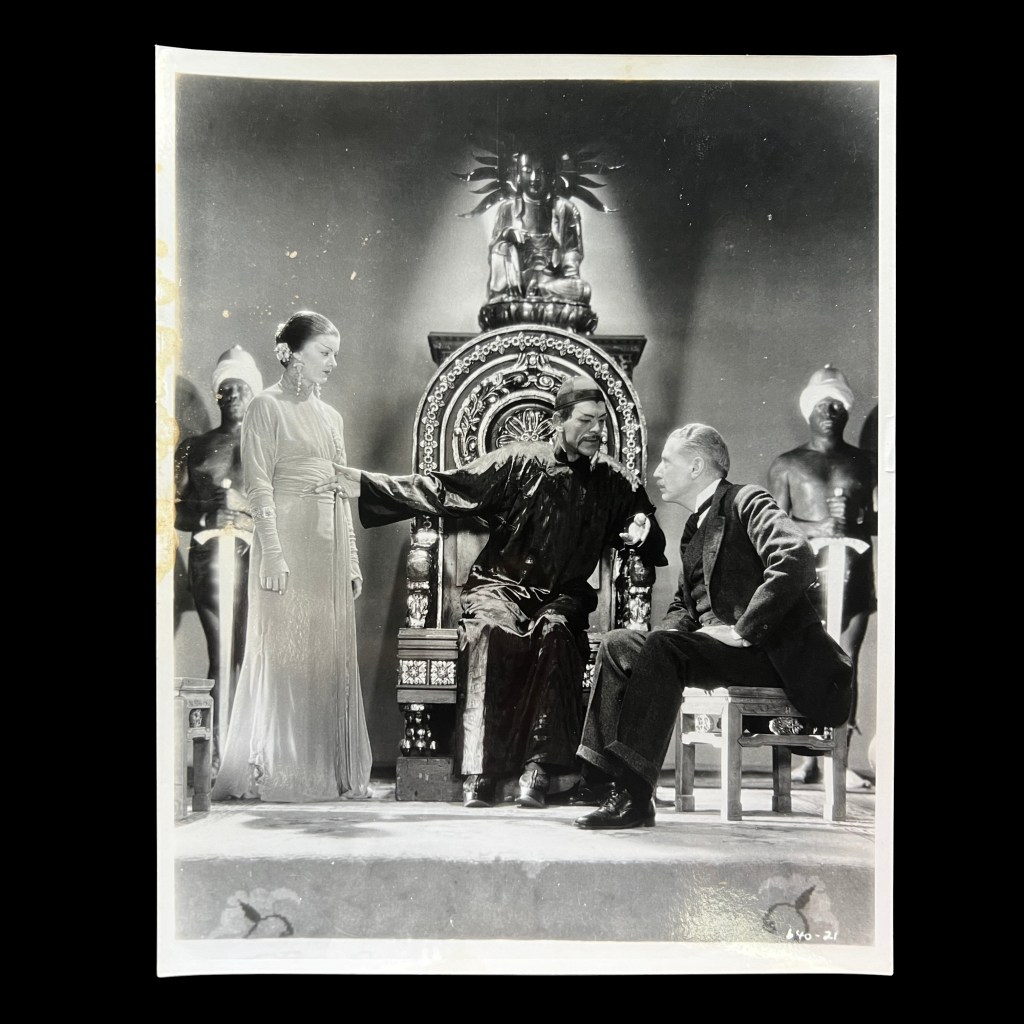

In 1871, Harper’s Weekly published a wood engraving depicting the interior of a San Francisco Chinese temple, a rare print subject before the 1906 earthquake. Clues suggest it shows the main hall of Eastern Glory Temple located off Jackson St. on St. Louis Alley.

Eastern Glory Temple was privately owned by physician Li Po Tai (1817–1893), an immigrant from Guangdong who opened a general store and apothecary across from Portsmouth Square. His temple was featured in California newspapers in February 1871, just before Harper’s illustration that March.

Despite being called a “Buddhist temple” in some popular accounts, there is no Buddhist icon displayed in the main shrine hall. The central icon is the Northern Emperor, a celestial deity popular among early Chinese immigrants from southern China.

Contemporary newspaper reports claim the icon to the far left was the “controller of fortunes” named “Choy Pah.”

The icon to the far right was a famous military general named “Tun Goa.” The next room over holds a shrine to Guanyin (not illustrated), the sole Buddhist figure, which newspapers describe as a “Cinderella” who is “treated cruelly by haughty women [and performs] act of charity.”

In addition to the Northern Emperor, the central altar displays the famous general Guandi and righteous official Hongsheng. To read more about Li Po Tai, see Tamara Venit Shelton’s Herbs and Roots: A History of Chinese Doctors in the American Medical Marketplace (2019).

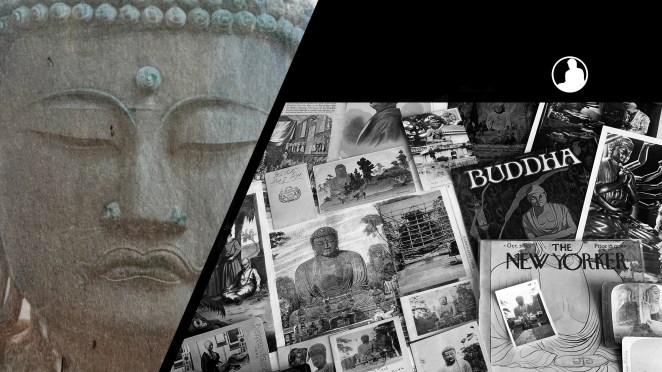

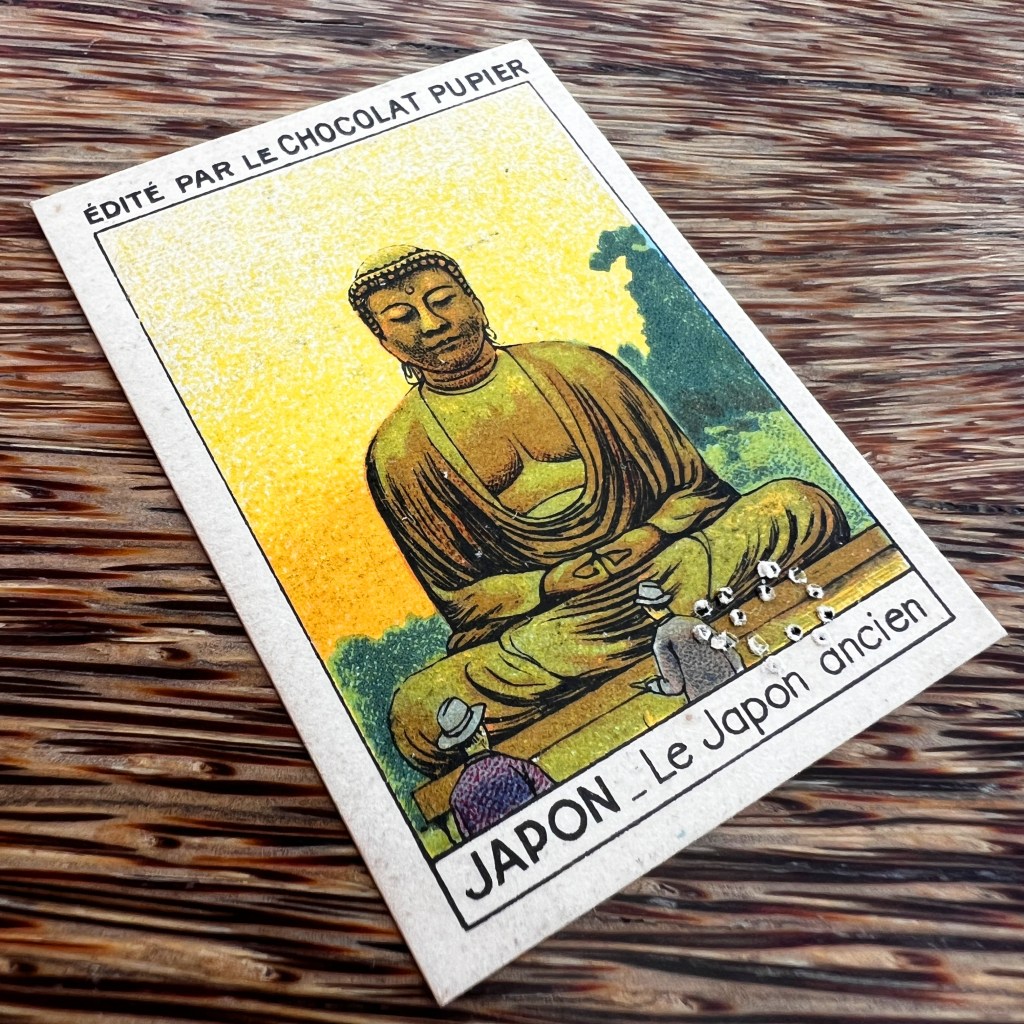

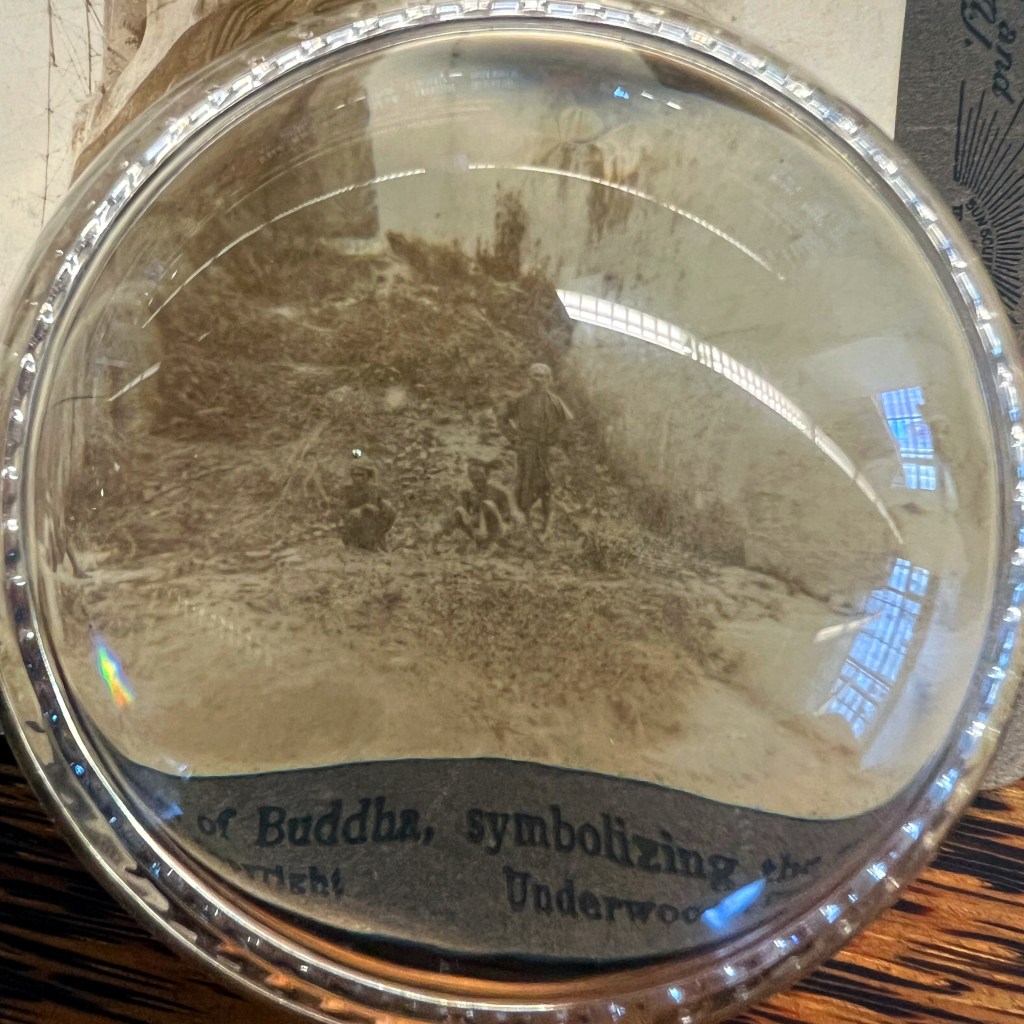

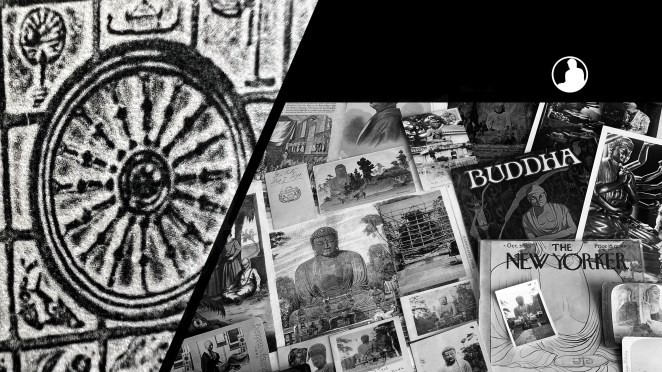

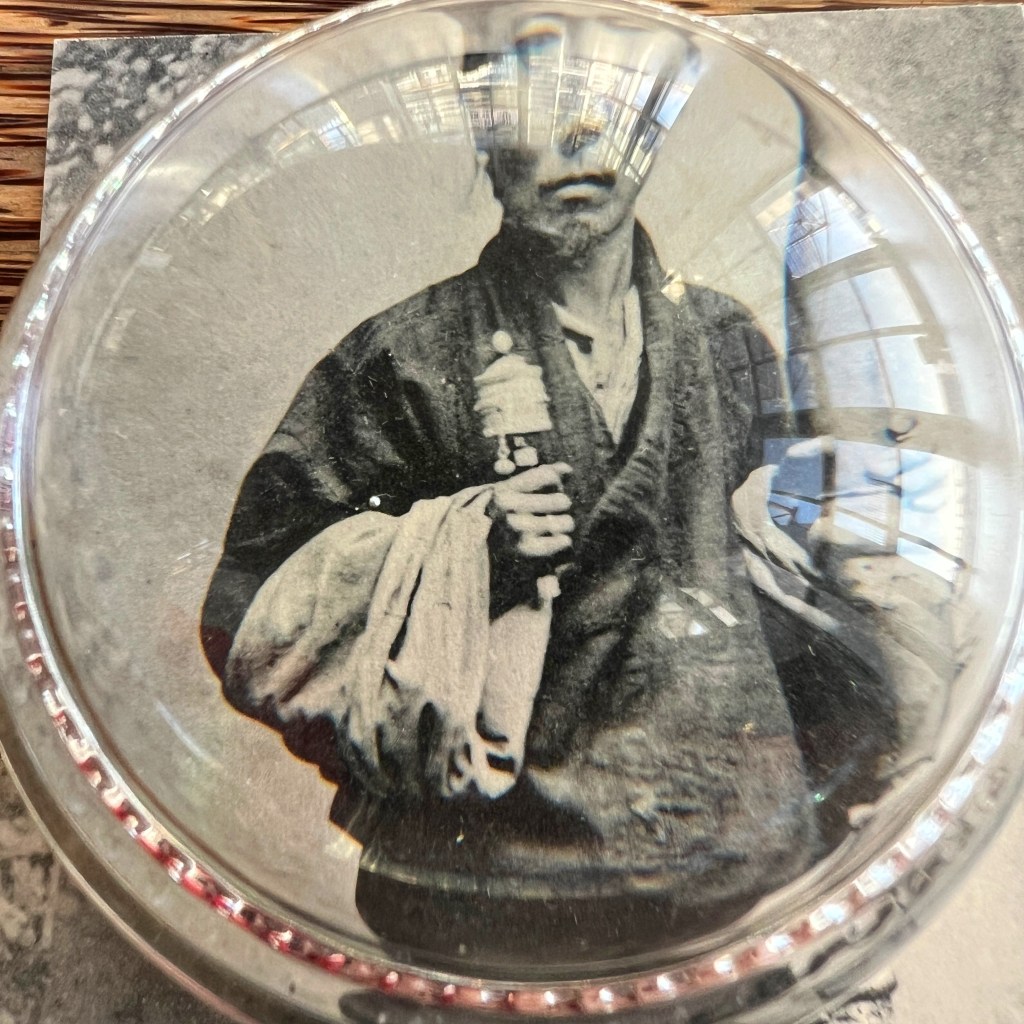

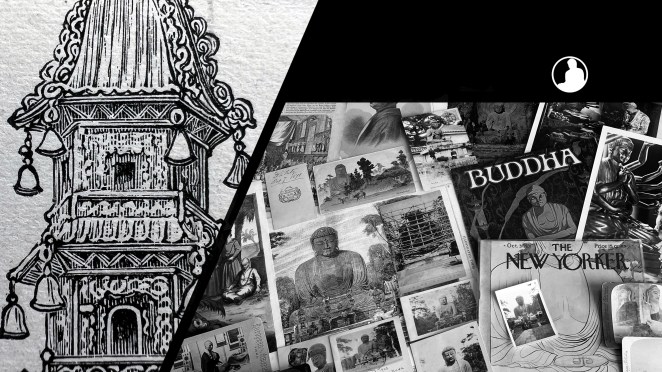

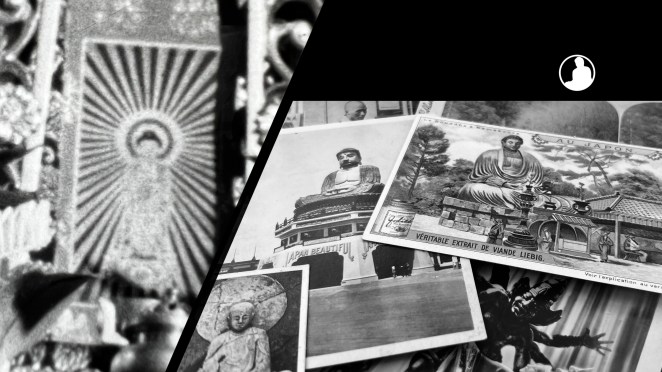

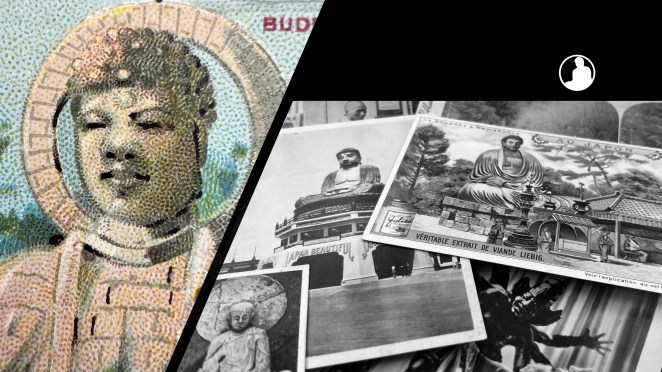

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Chinatown (US):

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: