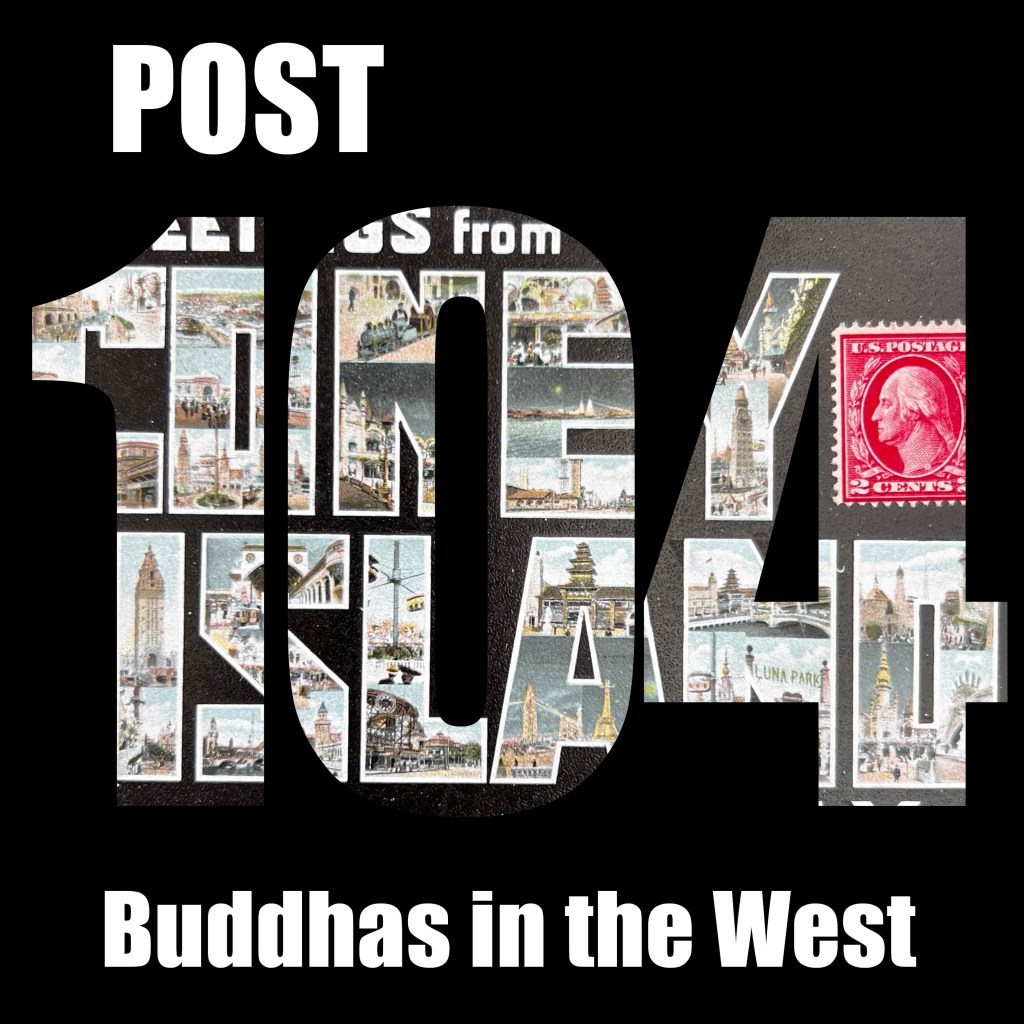

For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

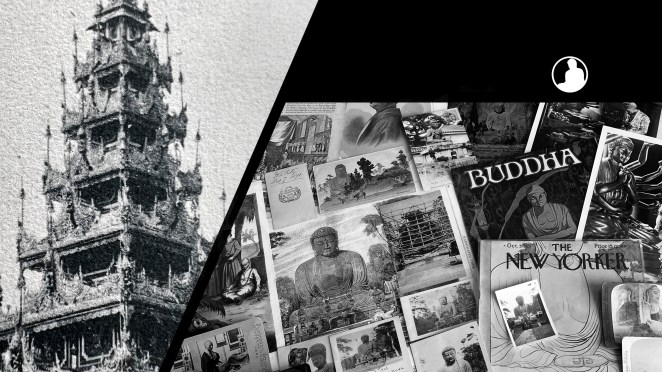

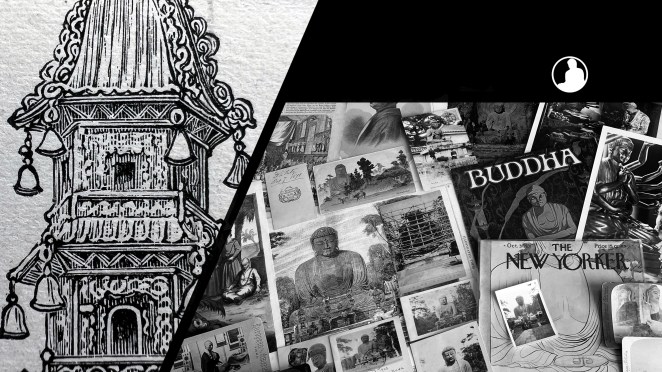

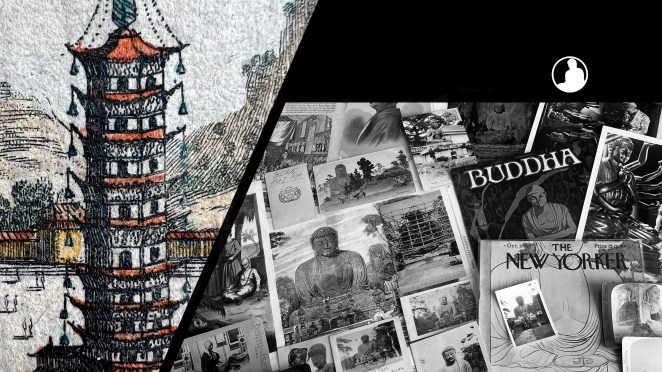

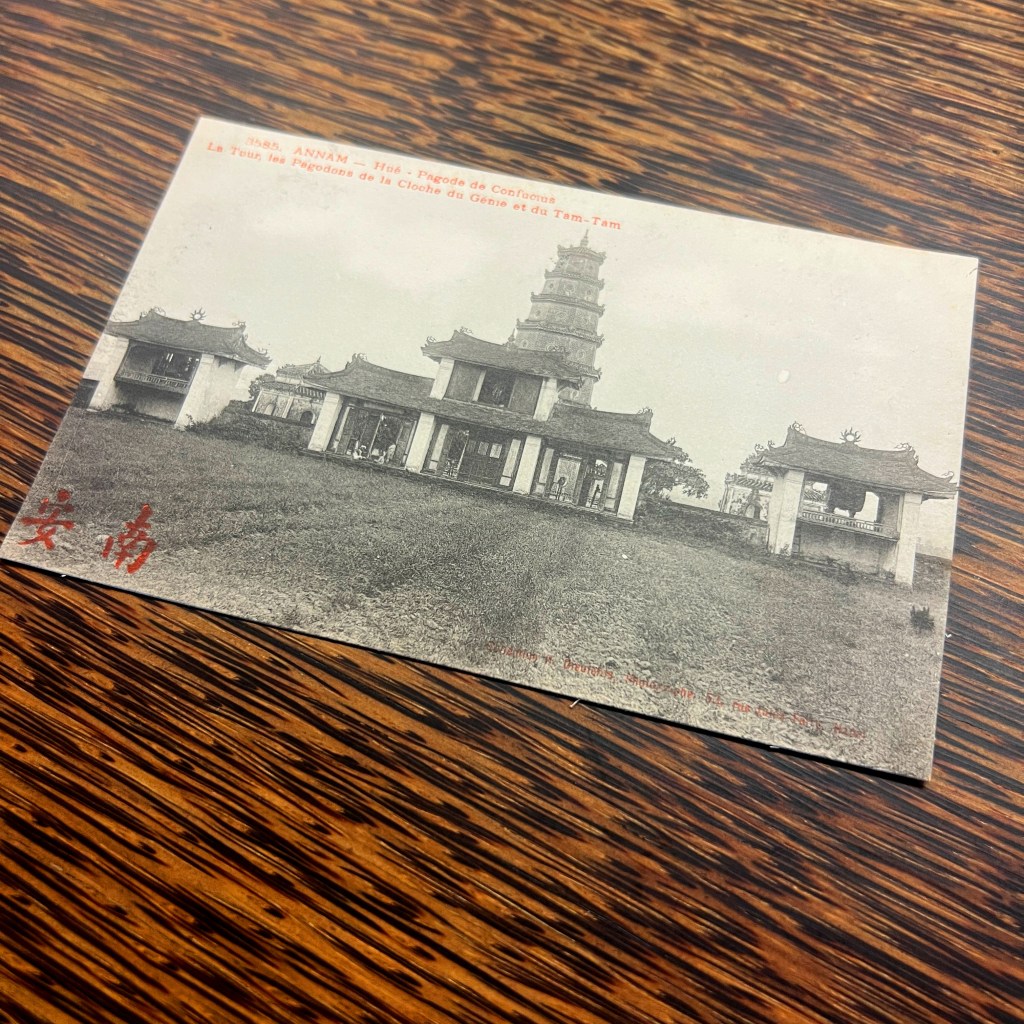

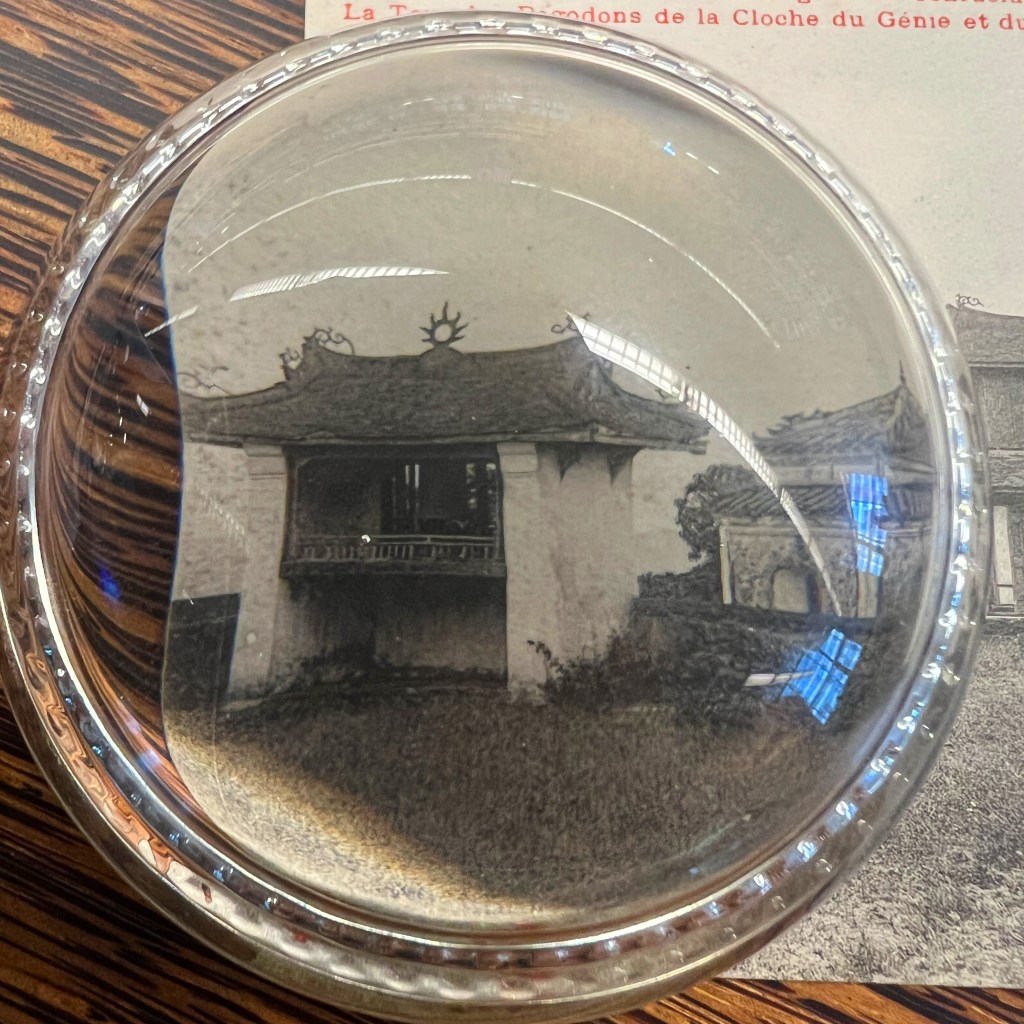

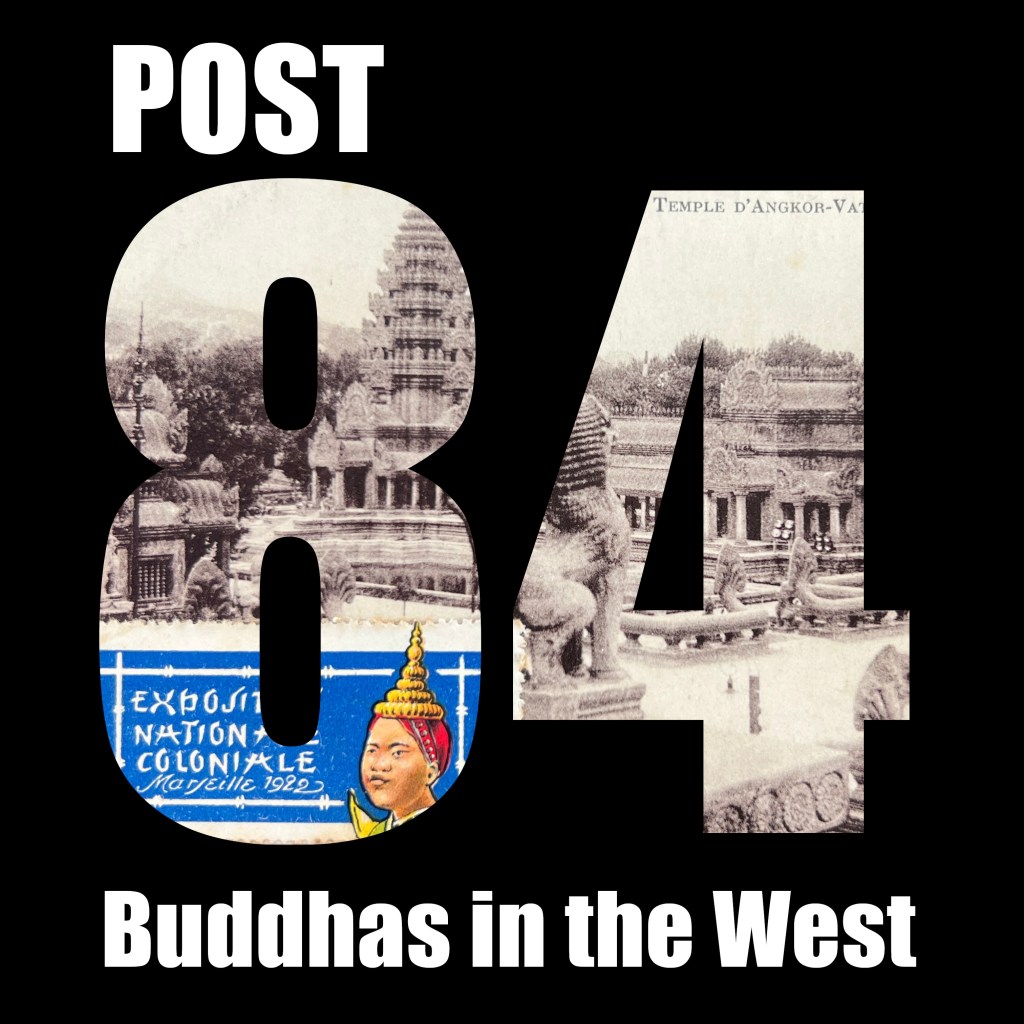

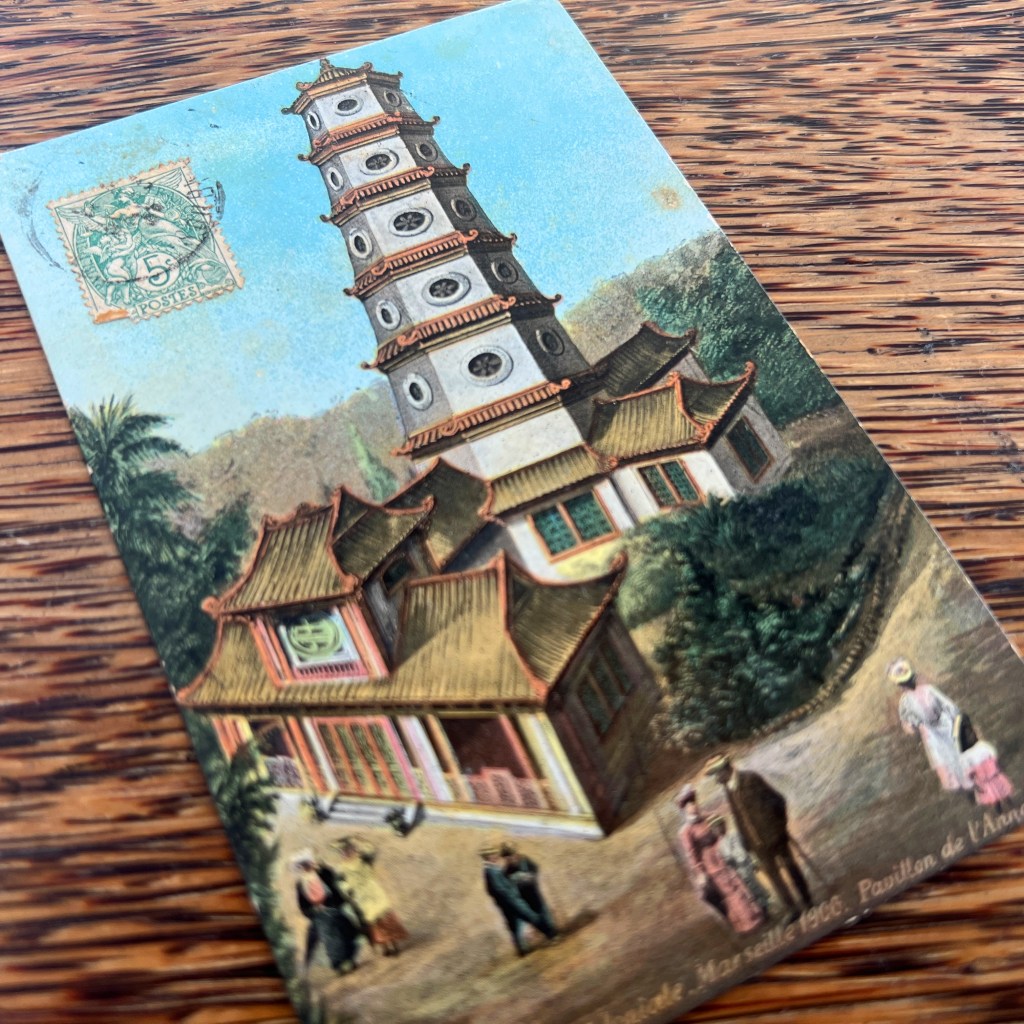

Following the success of colonial pavilions at World’s Fairs, France initiated its own independent Colonial Expositions in the 1890s. In Marseilles in 1906, famous architectural sites from French Indochina were reconstructed, including a towering Buddhist pagoda representing Annam.

Jules Charles-Roux, organizer of the colonial portions of the Paris World’s Fair of 1900 and head of the 1906 exposition, showcased the pagoda behind the main Indochina gate. The pagoda was also set at the head of a replicated “Hanoi road” populated with real inhabitants of the protectorate.

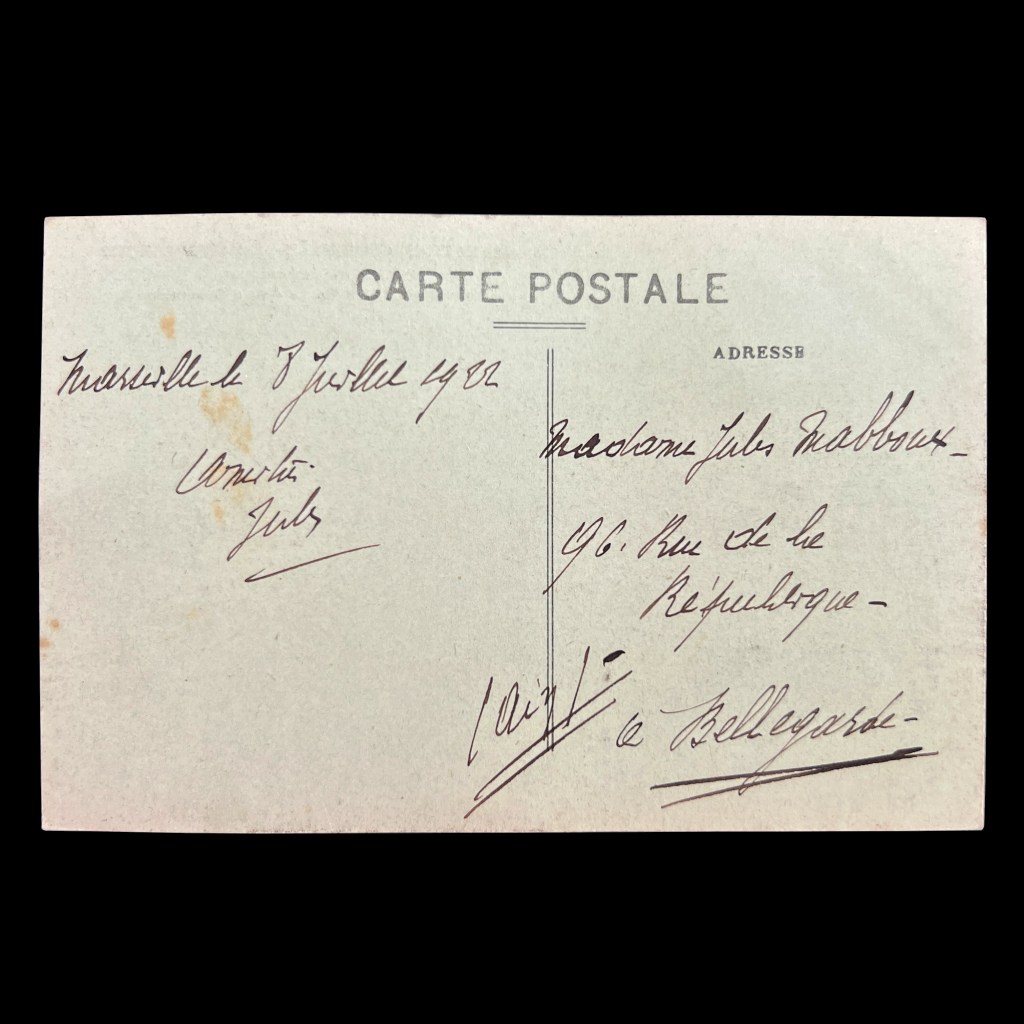

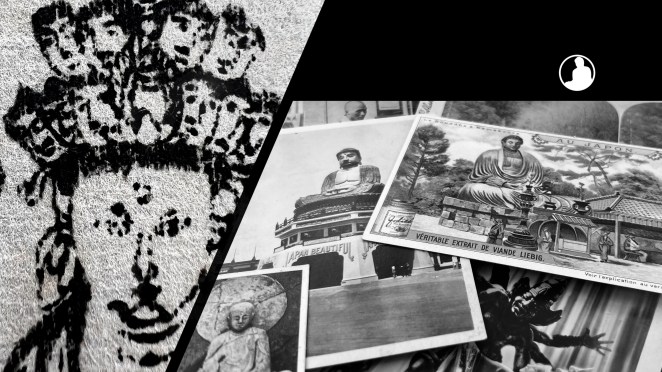

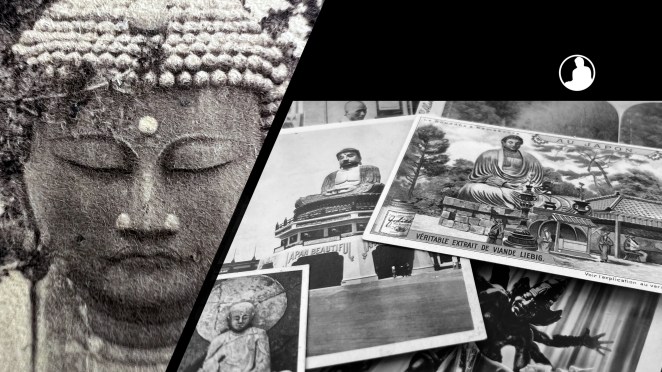

Held during the height of the postcard craze, the exposition grounds opened its own dedicated postcard pavilion. While the cancellation is unclear on the obverse, this card appears to have been sent from Marseilles; its destination was Port-Vendres, further down the Mediterranean coast.

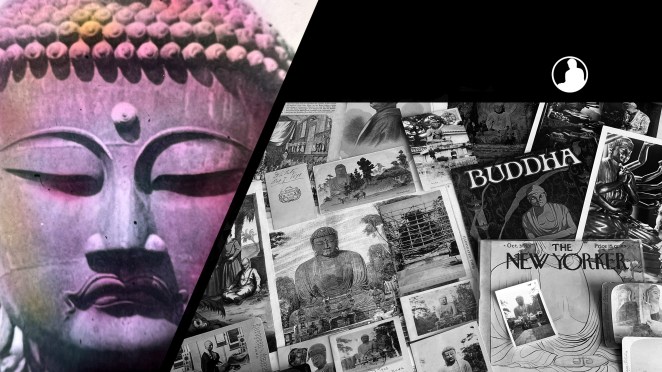

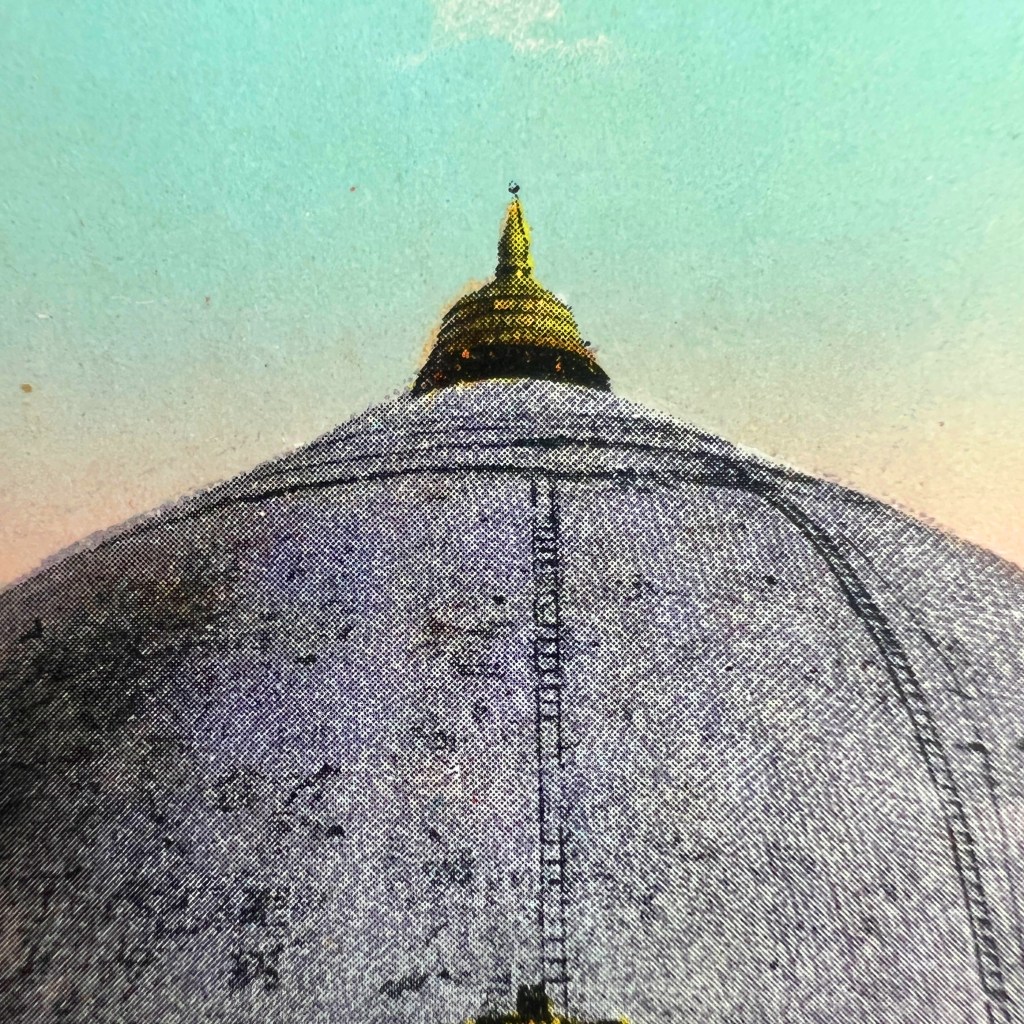

While often obscure in exposition literature, the “Annam Pavilion” was a replica of the pagoda from Tien Mu Temple, in the city of Hue, which was founded in 1601. The pagoda was a popular subject of souvenir photographs sold by studios throughout French Cochinchina, Annam, and Tonkin.

The following year, in 1907, Paris held another colonial exposition, but recreated a different pagoda to represent Annam. A photo illustrated book of the 1906 Marseilles Exposition is digitized by the University of Aix-Marseille, viewable here: https://tinyurl.com/mczsvn6s.

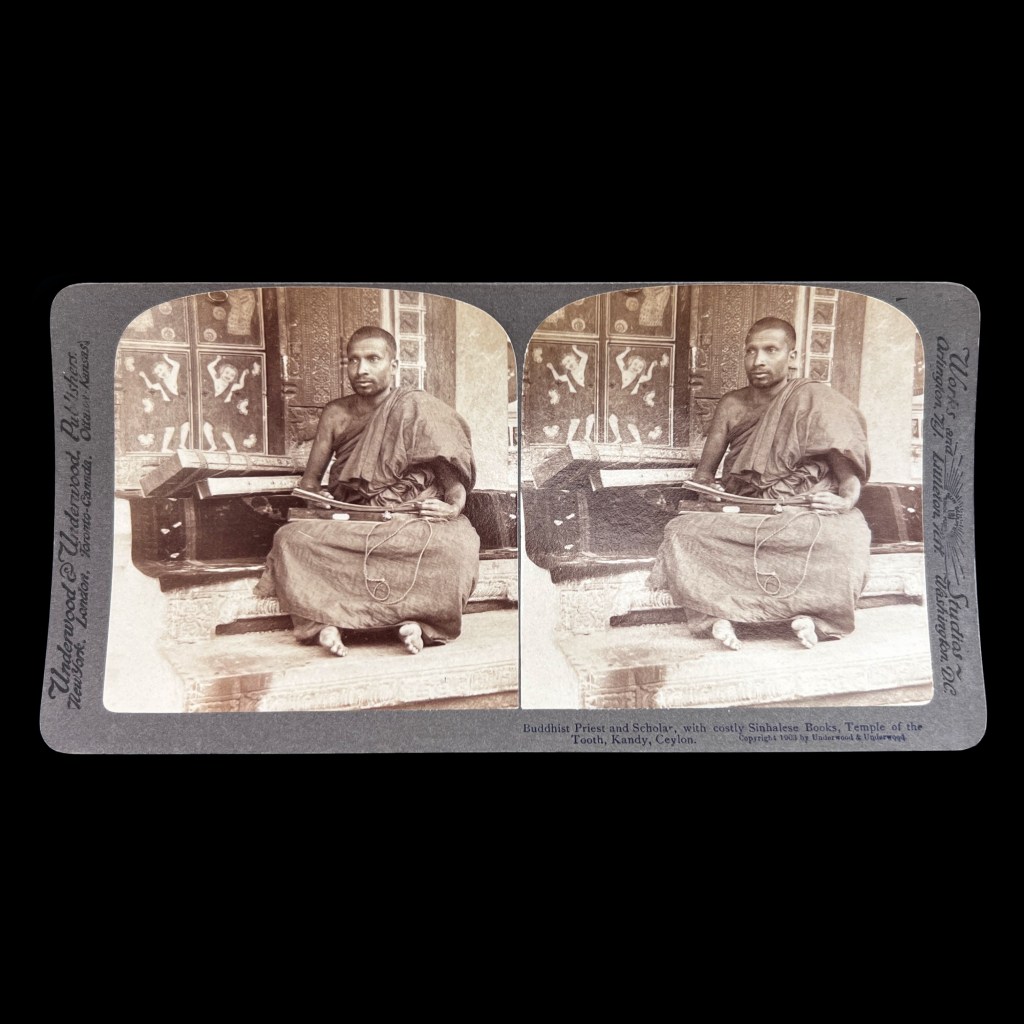

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Vietnam / French Indochina:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: