Under analysis, writing genres can be broken down into composite parts. Take a news article for example. Not only could we distinguish hard news, soft news, and fake news – which, for the sake of our class, I tell students to envision as separate genres – but we could also break down an article into its title, lede paragraph, photo caption, and so forth. Moreover, one could treat these as more than separate conventions that comprise the news article (macro-)genre, but (micro-)genres unto themselves, with their own specific purposes and intended audiences. This type of analysis helps students understand how genres are descriptive and analytical tools, not hard-and-fast prescriptive categories. In the end, genre theory helps give us an analytical leverage that can make our writing more effective.

I put this type of micro-analysis into practice when we first start to address scholarly writing in class. Students will often know the conventions of an academic paper, generally comprising an introduction, body, and conclusion. But do students realize these phases of a scholarly work each have their own functions and characteristics and, moreover, coordinate with one another to synergistically produce a more powerful rhetorical effect? In order to help suss out these distinctions, I’ve used the following activities to help students analyze and identify effective academic writing.

The Genre Scramble

Borrowing a practice from a colleague (Brian, Jackson, or someone else?!), I take an scholarly article or book chapter, print it out and cut it up into much smaller sections (maybe 20-30 sections depending on the selection). I then have students work in groups to piece the paper back together, using whatever clues they can find in the writing. In addition to subheadings, I try to find works that incorporate sequential language (first, second, third, on one hand, on the other hand, etc.), causal language (as a result, consequently, etc.) or self-referential language (as noted above, we will return to this point, etc.) to help in this process.

At one level, this helps students realize they already know a lot about the structure of scholarly writing. At another level, this helps train students to observe the usage – and practical utility – of transitional devices, or the numerous other linguistic cues that situate a phase of writing into an overall composition. This game, which I actively make competitive, is used as an opening activity for a class, getting students thinking and moving since most will clear out desks and arrange the slips of paper on the floor. (I typically allow 15 minutes for this activity, including a quick class discussion about what cues each group used to help them out. Depending on time, I will sometimes skip this activity and jump to the Genre Jigsaw.)

The Genre Jigsaw

This works in the broadest strokes by dividing up a selected scholarly work into smaller (micro-)genres and having students work in small groups to perform genre analysis on their segments. The divisions could include the abstract, introduction, two or three argument subsections (such as methods, results, discussion), and conclusion. For each sections students have to discuss the rhetorical purpose, the intended audience, and any identifying linguistic characteristics (the Genre Scramble help with this aspect).

To help model this kind of analysis, I first talk about the title as a (micro-)genre, an often overlooked rhetorical aspect of first year writing. As a class, we first brainstorm the potential purposes of an academic title (to summarize, to entice, to establish tone, to establish ethos?) and compare these titles to titles of other kinds of writing (how is it different from a news article or novel?).

Next, in a move that is sometimes confusing, we try to discuss audience and how it changes throughout an article. Since most folks intuitively think of audience demographically (age, gender, race, education level, etc.) it is hard to see how the audience may change in the process of reading. To start this discussion I have the class think about where they may just encounter a title of a work (bibliography, table of contents, in-text reference, etc.) and ask them to brainstorm about the mindset of a reader. For example, why would someone be looking through a bibliography? Maybe because they are looking for works relevant to their interests, thus the audience may be someone who is doing research and looking for key words or phrases. This gives us some information about the types of things we may want to include in our titles. Moreover, I guide conversation to how that audience may change when they shift to various phases of the essay (when are readers the most engaged, when are they most likely to read over sentences or passages, when are they the most critical or skeptical, when are they hoping for a summary of ideas?) This points to how the audience expectations change and how writing can accommodate that change.[1] They return to this point during their group discussions.

Lastly, we turn to a discussion about the language conventions of a title. Given what we analyzed about purpose and audience, what language could be included into a title? What can we notice about the language of the title of the work we are analyzing? I often end by noting how it’s pretty common in the humanities to structure a title with a colon in the center (the “colon construction”), looking something like this “Generality/Catchy Phrase: Specificity/Descriptive Statement.”

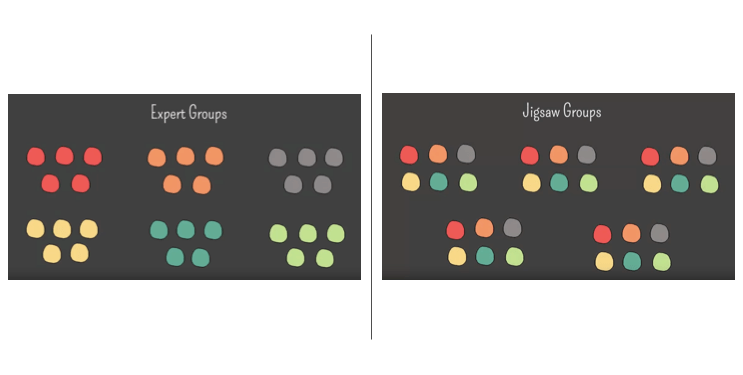

Using the analysis of the title as a model and applying the Jigsaw Method (I originally called this “Divide and Conquer” before learning of the Jigsaw) students then break up into Jigsaw groups, with one student taking responsibility for each phase of the scholarly work. I usually give an overview of the argument of the selected essay, since each student will only be reading a portion of the work (its possible to assign the essay as homework, too). Then students responsible for each phase meet with one another in Expert Groups to identify and discuss the audience, purpose, and specific linguistic cues. Armed with their insights for each phase, they then reconvene with their original groups and discuss the whole essay, trying to map out how the purpose and audience changes at the micro-level throughout the essay and attempt to create a bank of transitional words that appear in each phase. During class discussion, groups share their insights with one another.

While I’ve always enjoyed the analysis of my students, this can be a challenging exercise, especially if the scholar’s argument is complex or otherwise difficult. I’ve come to provide a decent summary of the article first so student can focus on genre analysis, not just comprehension. During class discussion I’ll have groups try to identify the thesis, or areas of strong or weak evidence. Overall, the purpose of this exercise is to have students work together to analyze different phases (or micro-genres) of scholarly writing and try to adopt certain strategies into their writing.

Notes:

[1] One example I like to give regards the use of personal anecdotes in writing. Scholarly readers are more likely to allow anecdotes in the introduction of the essay, since they know there may be an attempt to catch the reader’s attention. On the other hand, scholarly readers tend to not expect anecdotes in the body of an essay, especially when they hope to see formal argumentation regarding the main claims of the essay. In this case we can say reader are more critical and expect to see argumentation.

I’m continually amazed how the efforts of random bloggers make my life as a writing instructor all the more easier.

I’m continually amazed how the efforts of random bloggers make my life as a writing instructor all the more easier.