For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

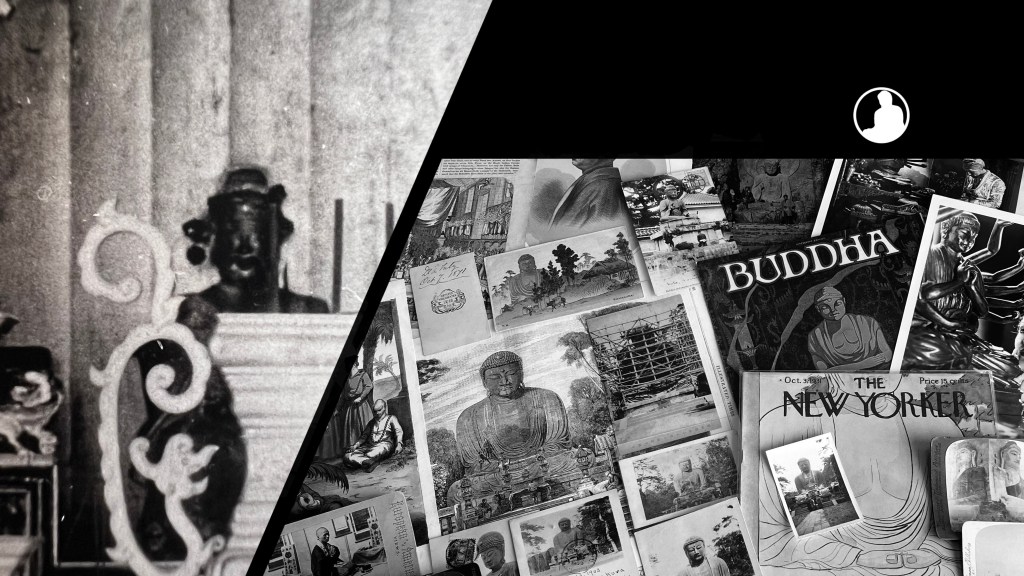

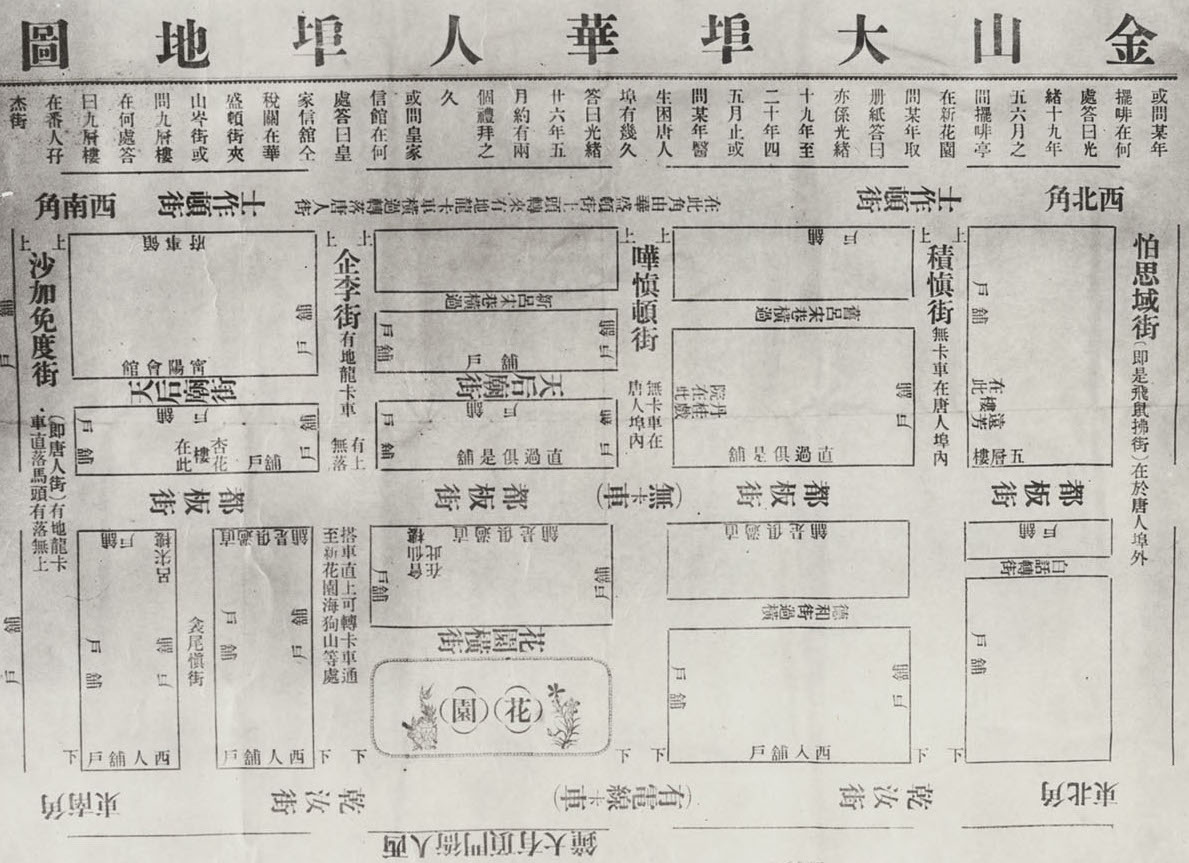

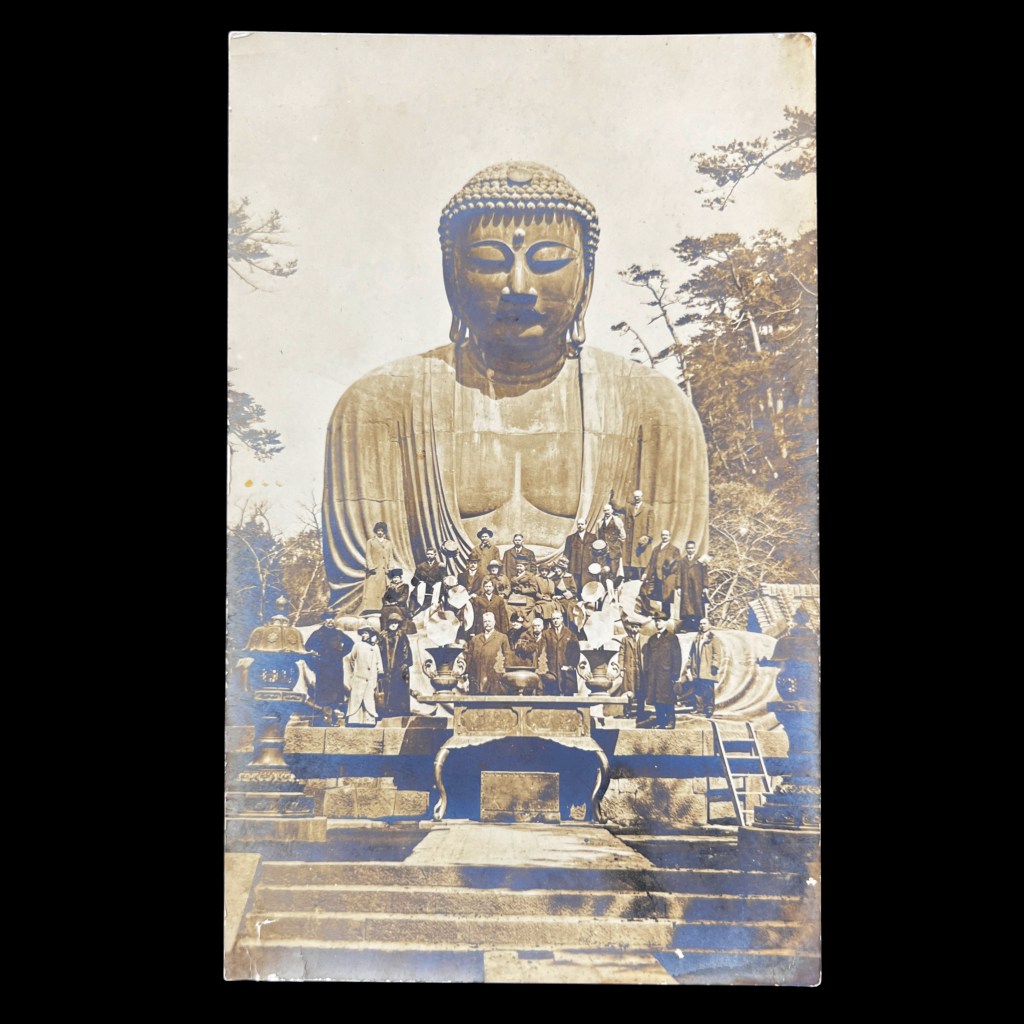

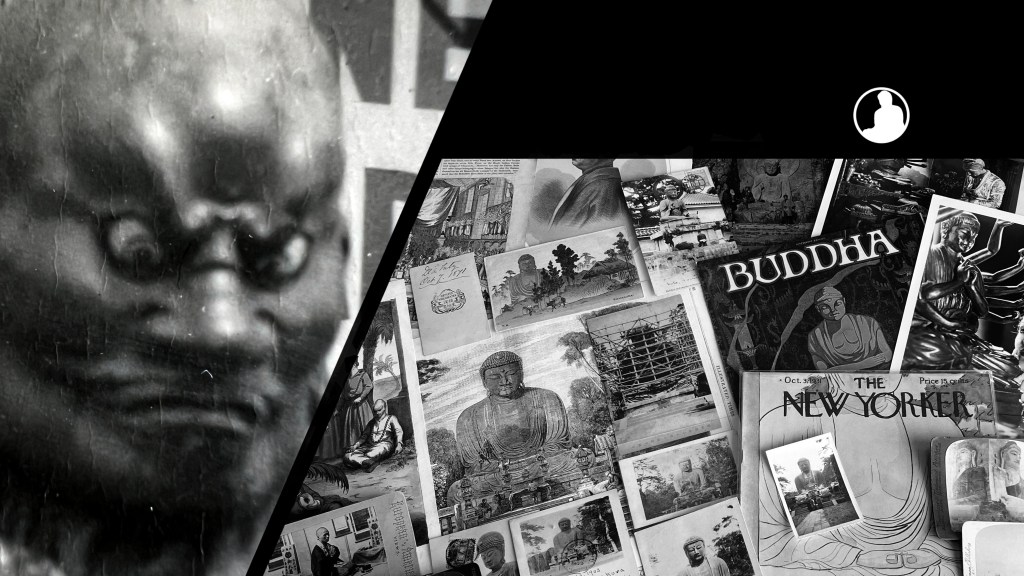

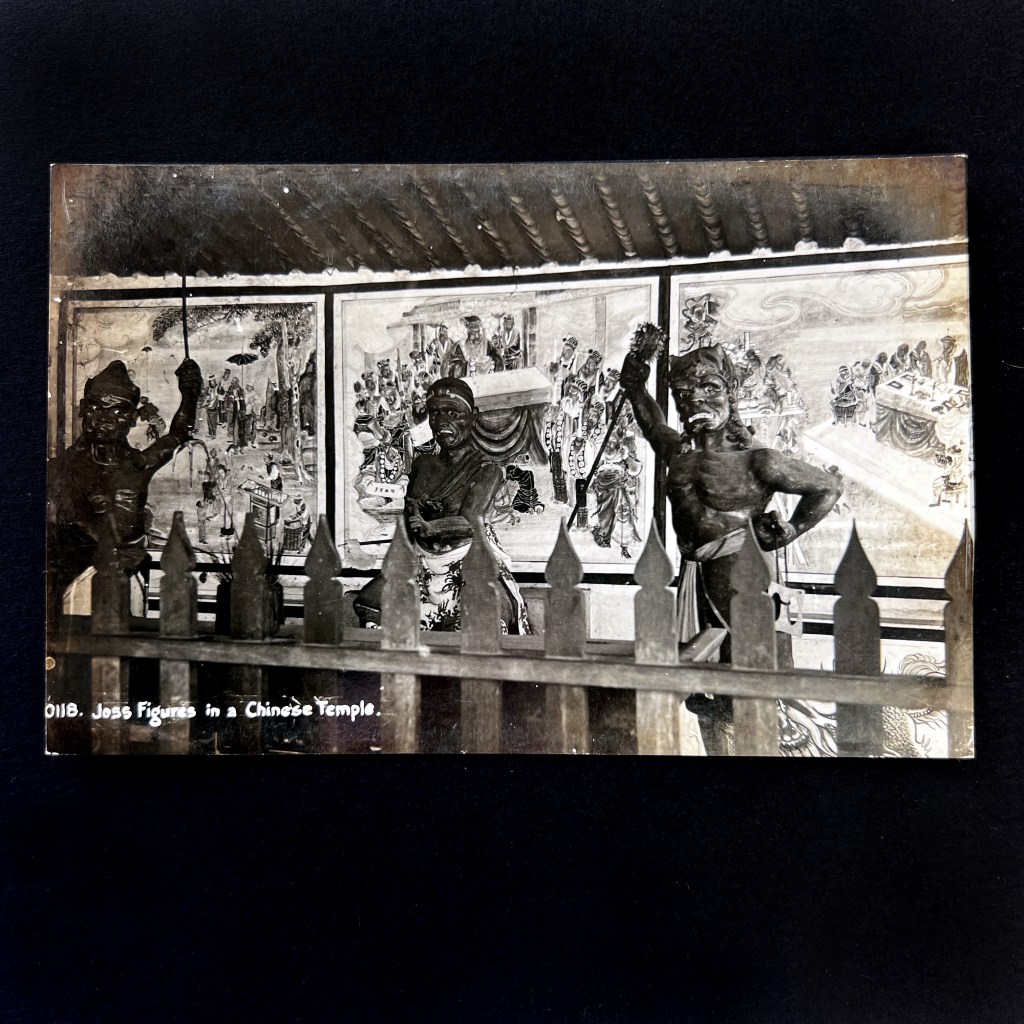

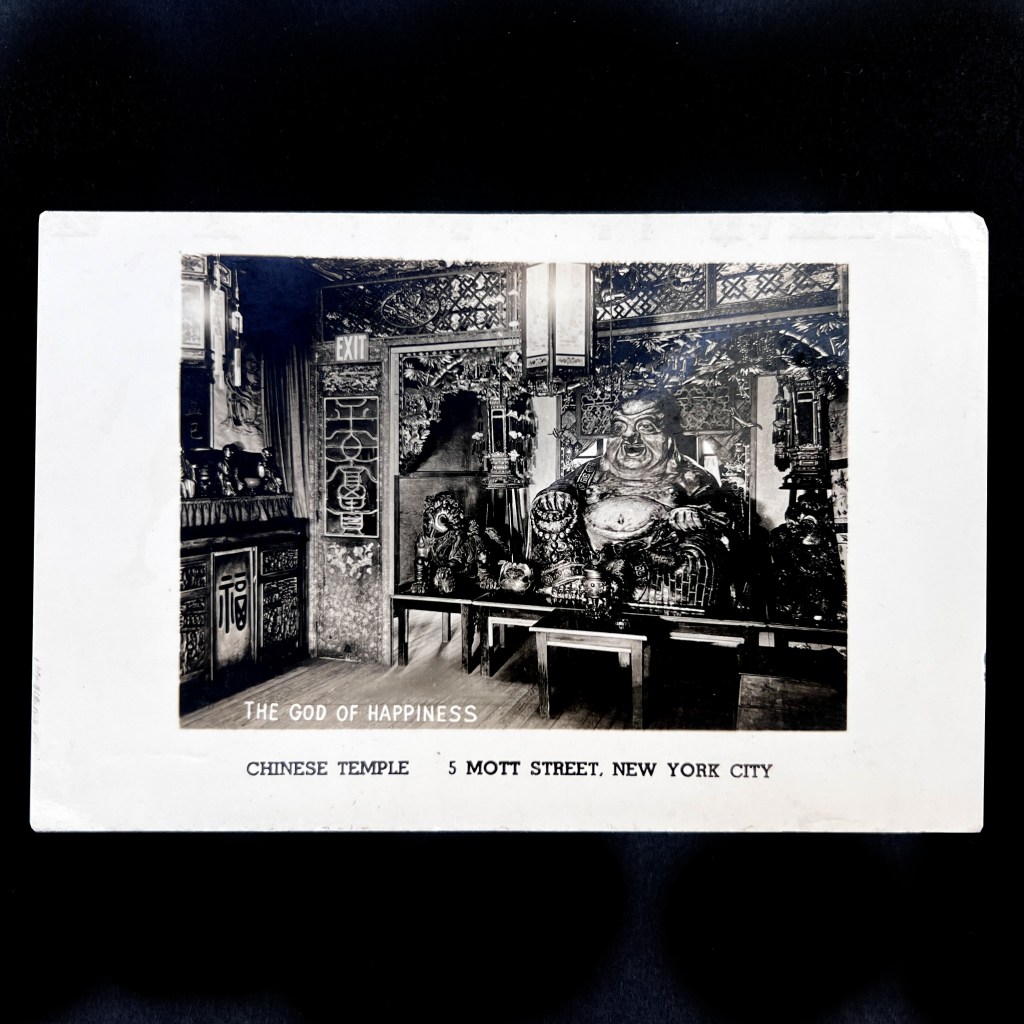

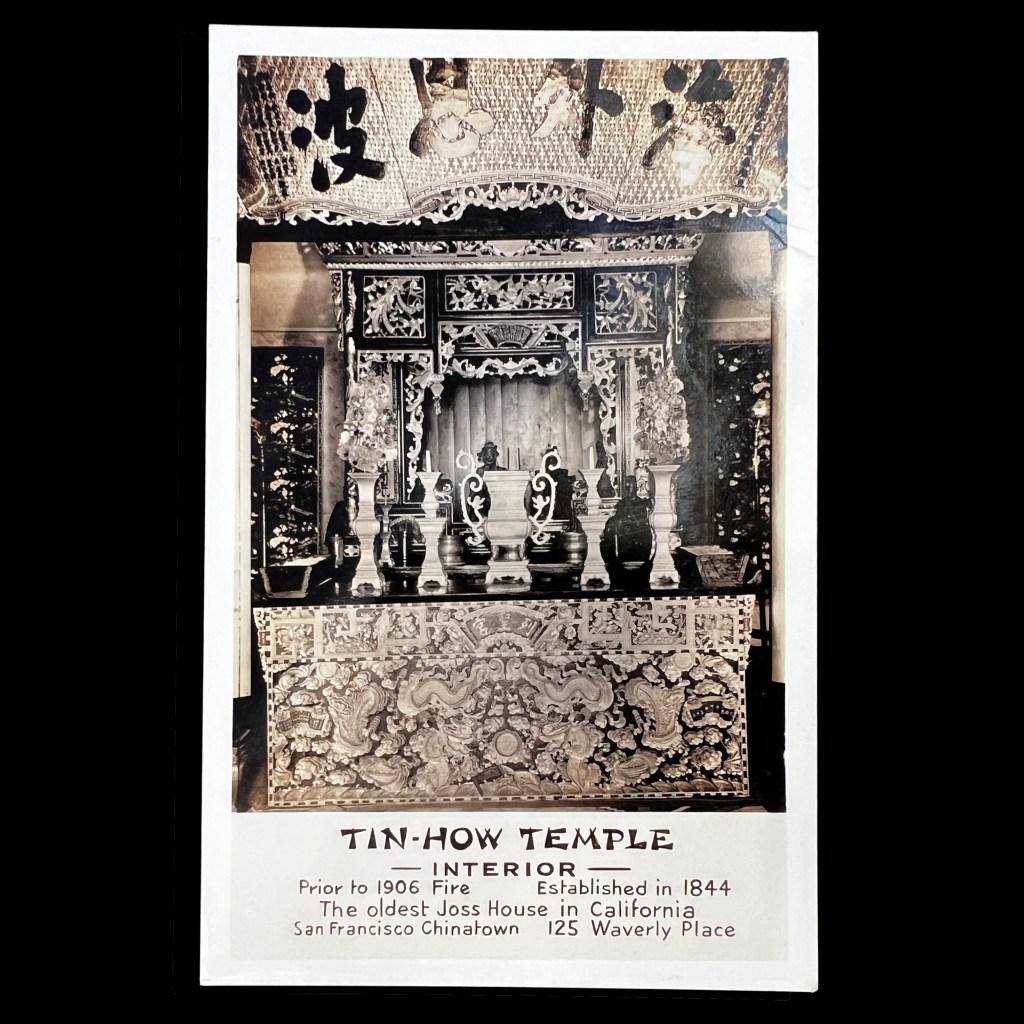

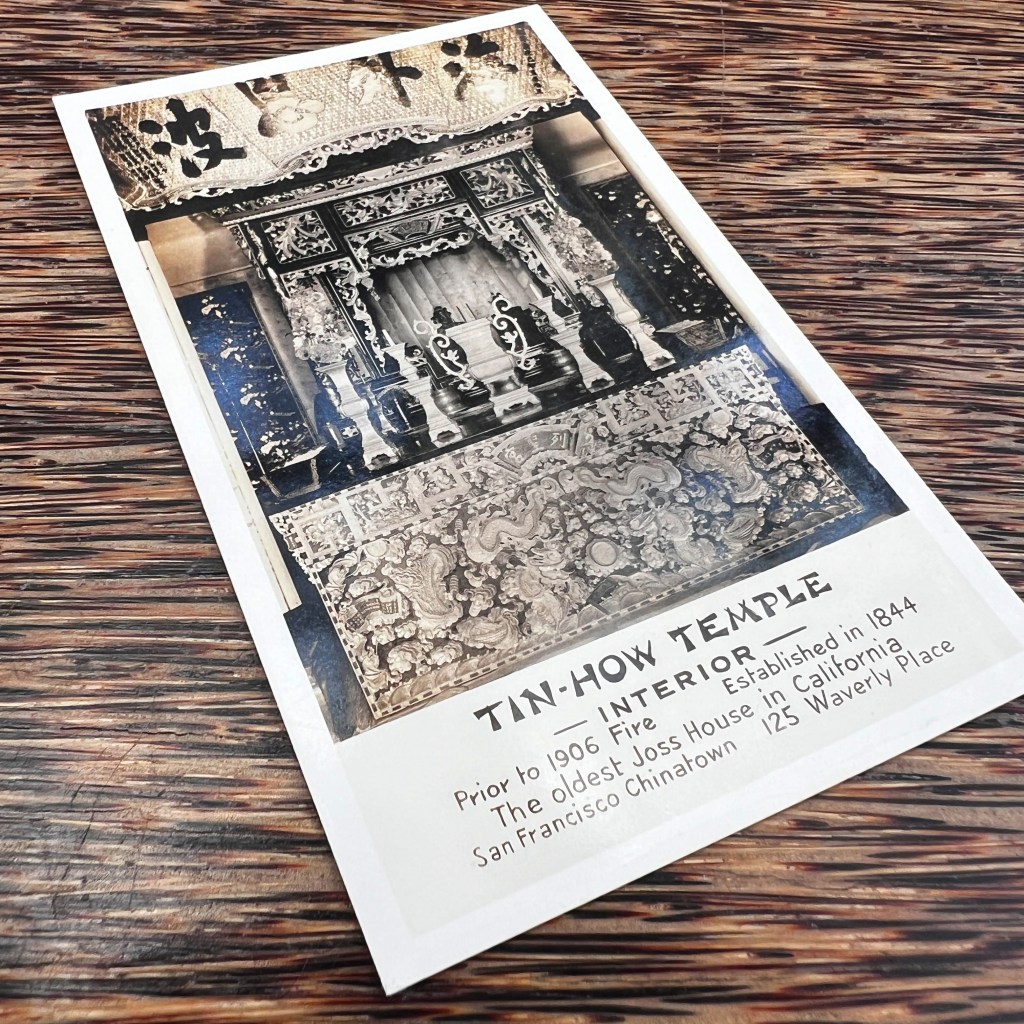

After the 1906 earthquake, San Francisco’s Tin How Temple was one of a fraction of Chinese religious institutions to rebuild, reopening in 1911 on the footprint of the original building. Despite the caption, this photo does not show the pre-1906 altar, nor is it a San Francisco temple.

Tin How, the Empress of Heaven, also known as Mazu, was popular along China’s southern coast and revered for her protective powers, especially at sea. Many early Chinese immigrants erected temples dedicated to her and other deities across North America.

The photo shows the altar of the old Chinese temple in Grass Valley, identifiable by the large carved inscription board reading “Waves of favor cross over the seas.” It’s likely the postcard publisher saw a more lucrative opportunity in selling a visual “relic” of the lost Tin How Temple shrine.

Moreover, the Grass Valley temple was dedicated to Houwang, not Mazu, yet both locations were alternatively called the Temple of Many Saints, seen carved on the altar façade from 1875. The Grass Valley temple fell into disrepair by 1933 and was closed soon thereafter.

The altar was preserved and is now displayed at the Nevada Firehouse No.1 Museum. For more history on the Grass Valley temple, see Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson’s Chinese Traditional Religion and Temple in NorthAmerica, 1849–1902 (2022).

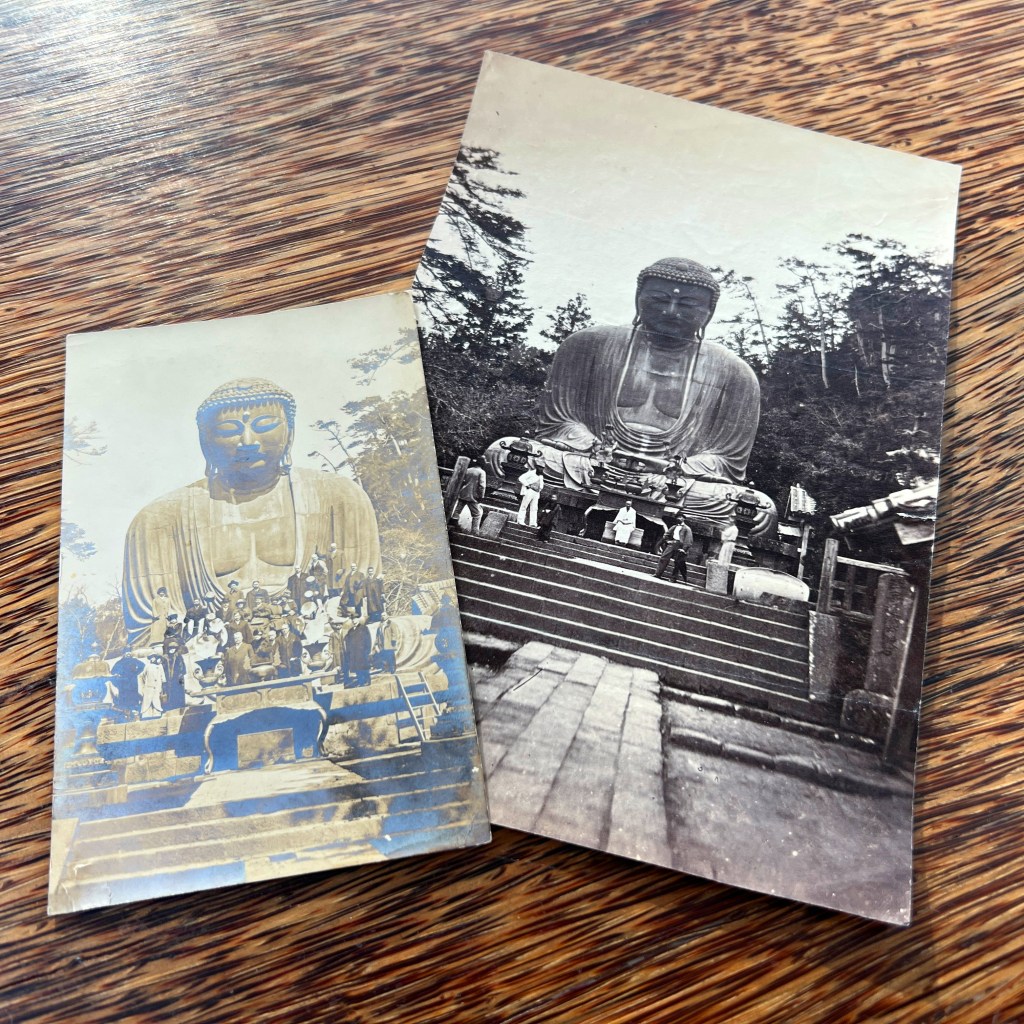

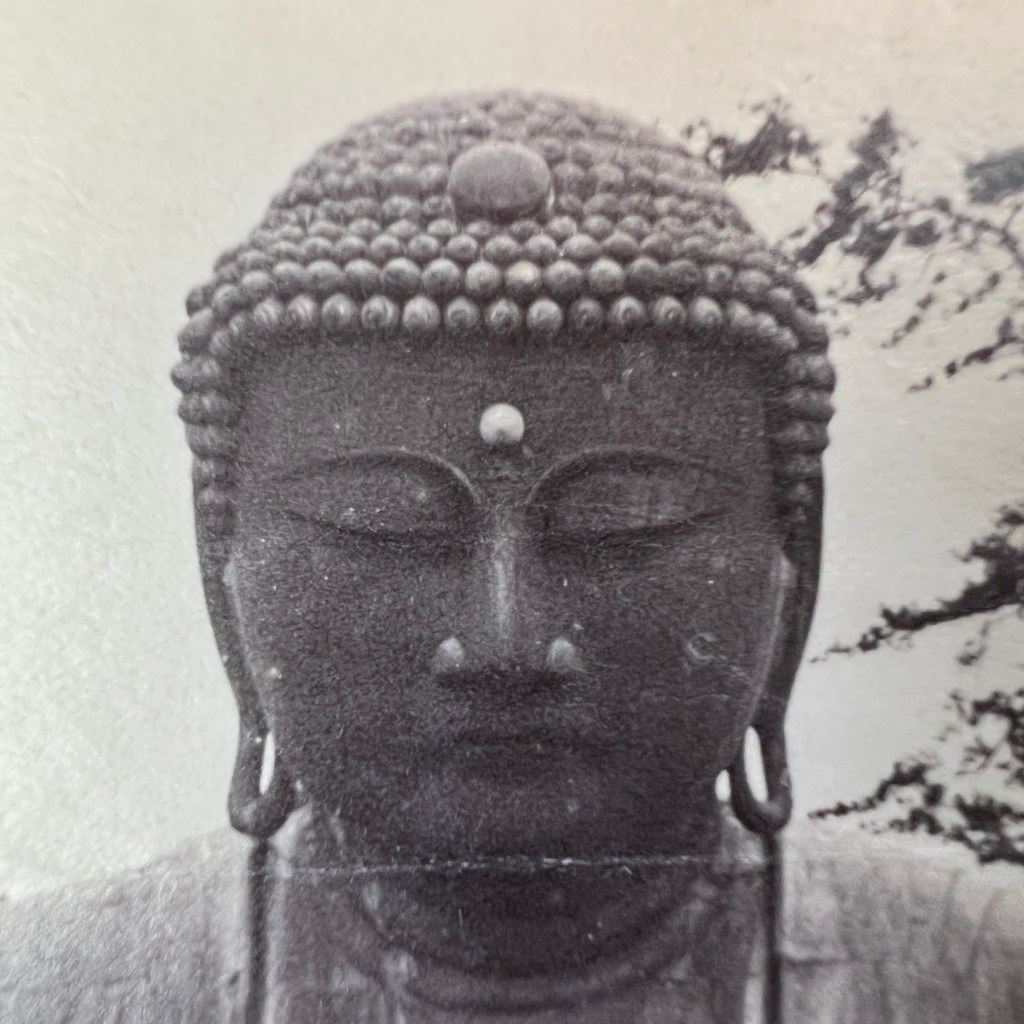

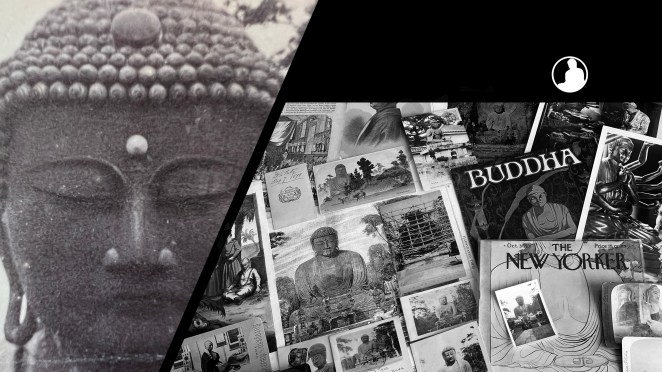

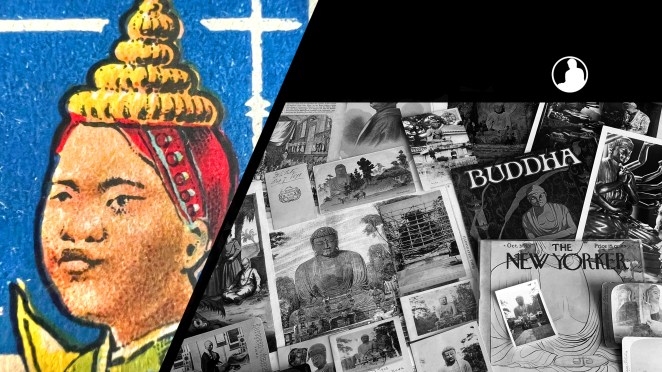

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Historical Real Photo Postcards:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: