Preface

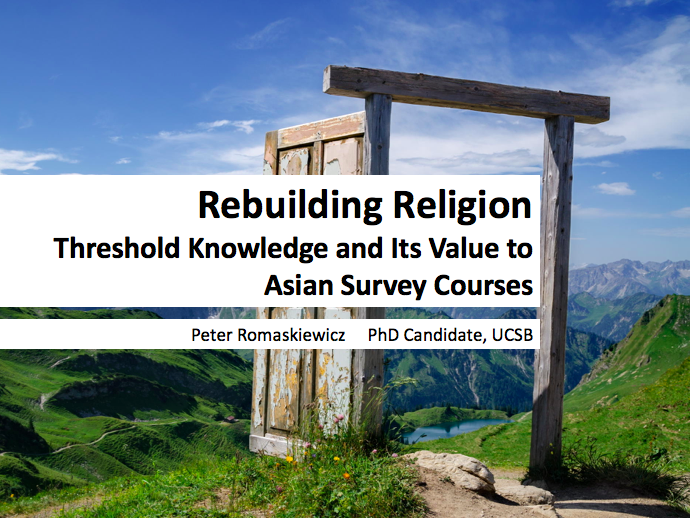

This past weekend I presented a paper at the Western Regional AAR covering some of the insights I’ve developed while teaching religious studies classes. The numerous blog posts on this site formed the raw material for several ideas, yet, not surprisingly, there were also a few ideas which did not hold up to further scrutiny when researching and writing this paper. The most significant was the realization that my identification of Threshold Concepts in religious studies may have been initially too broad, and I really only focus on one (albeit important) example here. Some of the big takeaways include the important distinctions regarding researching and teaching religions, the necessity of teaching content while critiquing it at the same time, and – as the title plainly indicates – the value of Threshold Concepts in the classroom. (The original proposal can be found here.)

I would like to thank the organizers and my fellow panelists, Maha Elgenaidi, Mahjabeen Dhala, Bat Sheva Miller, Jonathan Homrighausen, and Leigh Miller, for their insightful (and well-delivered!) papers and lively conversation.

Rebuilding Religion: Threshold Knowledge and Its Value to Asian Survey Courses

“Religion is not an empirical thing. In fact, one can say that ‘religion’ does not exist.” This is what I tell my students on our first day of class, which immediately presents a challenge since I stand in front of them, apparently, as a teacher of nothing. Of course, I immediately guide conversation as to how “religion” is a discourse, a historical and cultural construct, so thoroughly naturalized so as to appear a part of human nature.

Admittedly, this is a kind of cheap trick. In function, I hope to undercut a student’s enculturated, naturalized perspective of the world and provide a model of the critical inquiry I hope to engender. In form, however, I give away a possible answer to a question I really want them to ponder, “what is Religion?”

In designing a survey course on Asian religious traditions, I wanted to keep this question, “What is religion?” as the vibrant centerpiece. Historical critical methods and discourse analysis have an important place in university research and in undergraduate teaching, but so does providing a basic competency in the various religions. My challenge, as I saw it, was to provide a basic “religious literacy” in Asian religious traditions while at the same time destabilizing the very notion of “religion.” Finding a balance between these two approaches I believe is integral to survey classes, not just upper division courses or even graduate seminars.

In my attempts to find middle ground I decided to have my students, as a final project, devise a well-reasoned and well-argued definition of religion for themselves – and here is the spin – a definition solely based on the Asian content we cover, in an attempt to undercut the Christian-centric World Religions Paradigm, a topic we will return to shortly. This project was stimulated, in part, by an emerging pedagogical theory called “threshold concepts” which operate as transformative moments in a learner’s experience if they can be identified and harnessed in the correct way.

Since deconstructing and constructing definitions are vital to my course, let’s start with a few important ones.

World Religions Paradigm (WRP)

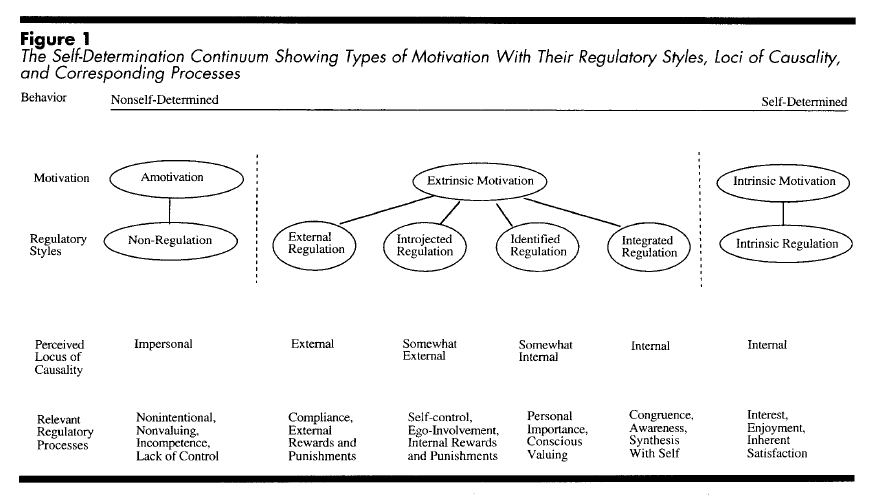

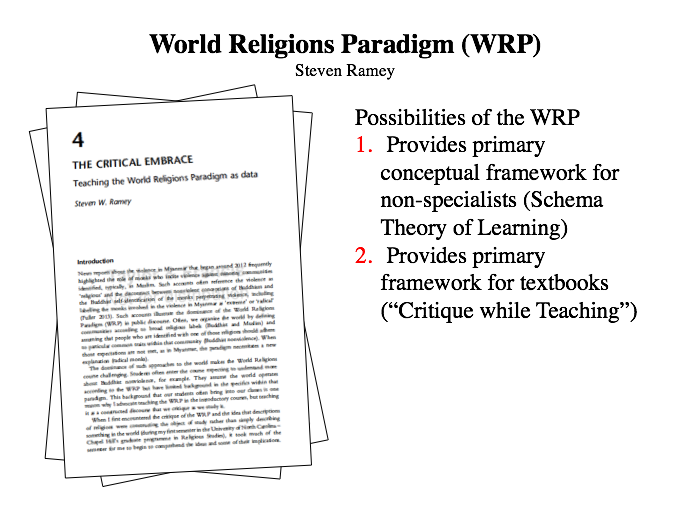

So what is wrong with “religion”? As many of us are already aware, “religion, religions, and religious” – to quote the title of the seminal article by the late Jonathan Z. Smith – are all value-laden terms.[1] Smith, Russell McCutcheon, Timothy Fitzgerald, Tomoko Masuzawa, Catherine Bell, among many others, have all pointed to the influence of Christian values in shaping the conception of the genus, the category, called “religion.”[2] Bell summarizes it well when she says, “As a prototype for religion, Christianity provided all the assumptions with which people began to address historically and geographically different religious cultures. In other words, as the prototype for the general category of “religion,” …Christianity was the major tool used to encompass, understand, and dominate the multiplicity.”[3] [Slide 1]

Slide 1

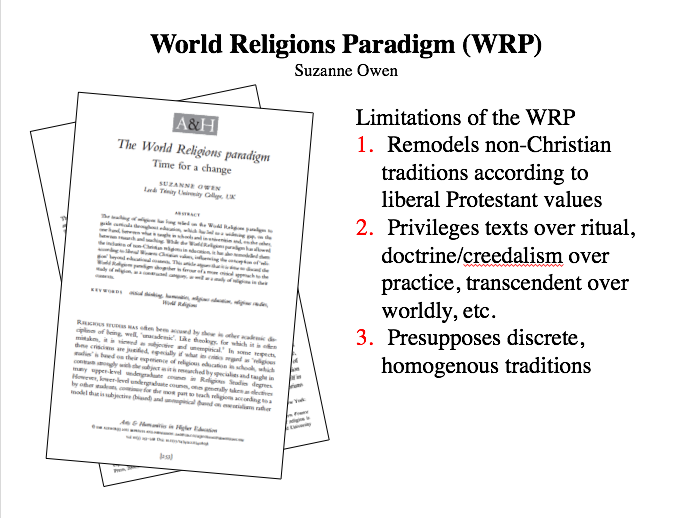

To signal this discursive power of “religion” and its far-reaching impact, scholars have begun to refer to a “World Religions Paradigm”– this is where all world religions are molded in the image of Christianity – a phrase first coined, as far as I can tell, by Bell herself.[4] In a recent provocative article by Suzanne Owen entitled, “The World Religions Paradigm: Time for a Change” we are confronted with the ramifications of such a paradigm in the classroom.[5] Owen, correctly in my view, wants to challenge the paradigm because it remodels non-Christian traditions according to liberal Western Protestant values.[6] There is also a tendency to privilege, for example, texts over ritual, doctrine over practice, and the transcendent over the worldly.[7] It also hypostatizes religions into discrete, typically homogenous, entities nominalized by calling them “isms” – such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Daoism, etc. This tends to overshadow a long complex history of interaction, synthesis, and internal division. [Slide 2]

Slide 2

This privileging and mode of discrete categorization has long been reproduced in the Western study of Asian religions,[8] but as Owen reiterates, as modern scholarship becomes more attuned to these problematic presuppositions, there remains a gap between what we (as scholars) research and what we teach, where this paradigm often continues unabated in the classroom.[9]

While it is imperative that we destabilize categories such as “religion” (or address any of these issues) in our research and our teaching, I am actually not convinced that we need to completely discard the World Religions Paradigm in the classroom as Owen seemingly suggests.[10]

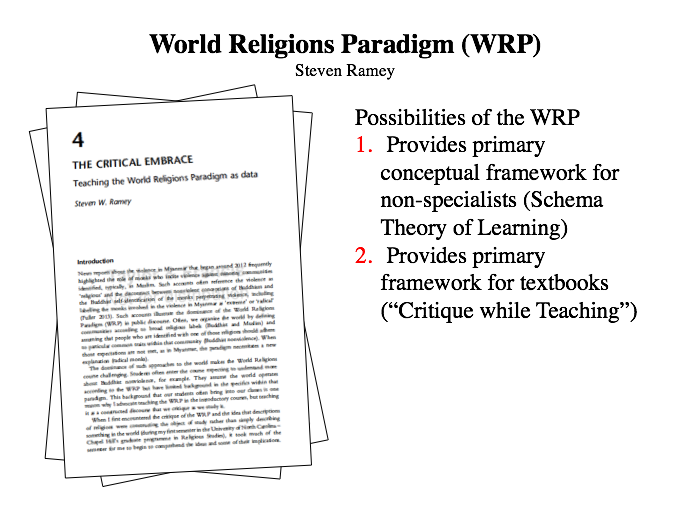

She admits that student expectations often drive the use of the paradigm in university courses; it is, after all, the primary conceptual framework for non-specialists.[11] Instead of viewing this as an obstacle, we can take it as an opportunity. In an edited volume entitled After World Religions, Steven Ramey argues that this familiarity with the paradigm provides an important starting point for student learning.[12] This follows an important principle in the Schema Theory of Learning which postulates that people primarily learn new concepts only after modulating pre-existing mental templates of the world, or in other words, “you gotta work with what you got.”[13]

Ramey summarizes his approach by saying, “This background that our students often bring into our classes is one reason why I advocate teaching the World Religions Paradigm in the introductory courses, but teaching it as a constructed discourse that we critique as we study it.”[14] Ramey calls this “critiquing while teaching,” whereby instructors can capitalize on the previous knowledge of students while also interrogating and transforming it.

This framework also allows for the use of traditional religious studies textbooks, an industry that widely accepts and perpetuates the World Religions Paradigm. For Ramey, these textbooks, with separate chapters on globally diverse “isms,” should become the target of student critique. Discussions can emerge on why certain subjects are included or excluded, or which organizational principles were employed, and how those choices reveal the assumptions and interests of the authors.[15] So, instead of taking textbooks as neutral descriptions of the world, they act as cultural documents that students can critically deconstruct. I quite recommend Ramey’s discussion of these matters, and I found this approach of critiquing textbooks to be quite useful in my course.[16] [Slide 3]

Slide 3

A third reason to critically utilize the World Religions framework is that it allows instructors to still focus on content that reflects phenomenal realities in our world. In 2016, the AAR was awarded a grant to produce guidelines related to the expected competency in religions for every university graduate; handily called a “religious literacy.”[17] A recent draft of these guidelines highlights the political necessity of understanding religions and religious actors. I would just like to briefly note that the “Learning Outcomes” reflect both a normative vision of religion as well as a more critical one, taking a blended approach as we have been describing here. [Slide 4]

Slide 4

To summarize, while the World Religions Paradigm remains highly problematic as a framework for contemporary scholarly research, with the correct approach, such as “critiquing while teaching,” its remains a useful tool in the classroom, or for those versed in Buddhism, an upaya, or “skillful method.”[18]

Destabilizing through Defining (or Rebuilding Religion)

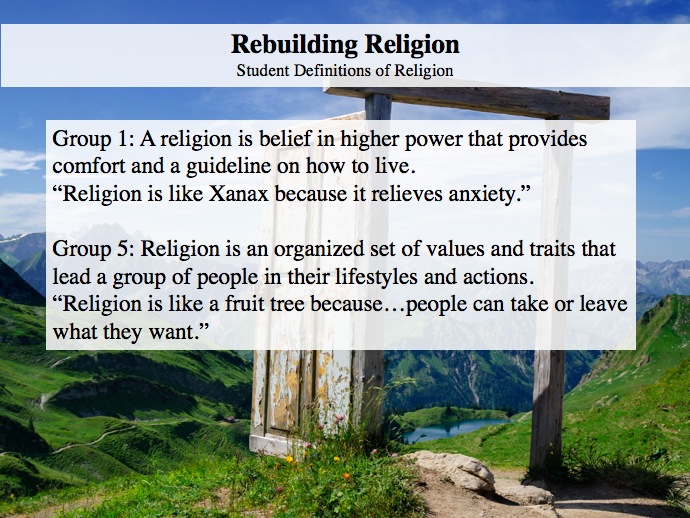

My approach utilized a close examination of definitions. On the first day of class I divided up the students into several groups and had each one craft a clear, one sentence definition of religion (with an illustrative metaphor to anchor it, which turned to out be pretty revealing of what students really thought of religion). [Slide 5]

Slide 5

Then we compare these to well-known scholarly definitions (EB Tyler, William James, Émile Durkheim, Clifford Geertz, Catherine Albanese, even Religion for Dummies) and see if we can identify any patterns, what constitutes the received “core dimensions” of religion. Things like belief, divine beings, and ethical codes are quickly targeted, which allows an easy transition into a discussion of the World Religions Paradigm and the guiding presence of Protestant values in these types of definitions.

Thus as a challenge, I ask my students to see if their definitions, and the definitions of scholars, hold up in light of the Asian content we explore. They are tasked individually with crafting their own definition of religion, to rebuild religion, based on examples drawn exclusively from Asian traditions, and presenting it along with their argumentation as a final paper.

I have found this approach appealing because it emphasizes higher-order thinking such as analysis, evaluation, and creation, the three highest cognitive domains according to Bloom’s taxonomy. The purpose is not to create a perfect definition of religion, as if that was possible, but to see that all definitions of religion are constructed. This encourages students to envision different ways in which to organize their worlds.[19]

To help facilitate this process I regularly introduced several comparative themes which could be adopted for the new definition. Many of them come from the more traditional understandings of religion (mysticism, polytheism, sacrifice), while some come from philosophy (ontology, epistemology), and others I incorporate to force my students to take unconventional perspectives towards religious ideology (metaphor, nature, humor). [Slide 6]

While I did not include kindness or metta/loving-kindness as a theme, I did happen to incorporate ahimsa, non-violence. As a comparative theme, not only were students asked to understand the concept in the framework of Jainism where it was introduced, but also to see if they could find analogues elsewhere, such as Confucianism or Shinto. By using these lenses to build bridges between traditions, students were encouraged to look beyond the traditional building blocks of religion – belief, divine beings, and ethical codes – to find potentially new ones they could argue as central. The creation of the taxon of religion is now no longer naturalized, it is rhetorical and discursive.

Threshold Concepts (TC)

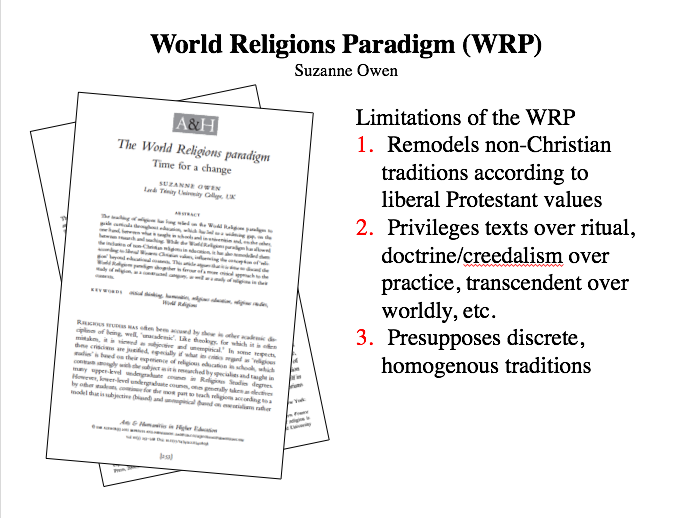

My curriculum design was stimulated by a pedagogical theory called Threshold Concepts, first introduced by Jan Meyer and Ray Land in a 2003 landmark paper. In the intervening 15 years there have been hundreds, even thousands, of articles developing this idea, thus I can only give the most general outlines here.[20]

Threshold Concept theory maintains that there are concepts, most likely found in all academic disciplines, which act as conceptual gateways or portals through which allow one to arrive at important, new understandings. Initially, this particular knowledge remains obscure because it cannot be easily assimilated into one’s existing meaning frame (the pre-existing mental schema[21]). But through regular exposure and practice one can enter a liminal space where familiar ways of seeing slowly fade. A person thus can enter new conceptual terrain that permits previously inaccessibly ways of thinking and practicing.[22] Threshold Concepts also tend to represent specific disciplinary knowledge, allowing students to think, practice, and talk like scholars of particular fields.[23]

This transformative property has emerged as the “superordinate and non-negotiable” criterion of a Threshold Concept.[24] Taking the metaphor of travelling through a portal, this means that, once mastered, these concepts alter how the learner views the world, often engendering what is described as an epistemic, ontological, or subjective shift.[25]

A second criterion noted by Meyer and Land is integration, whereby the formerly disconnected elements of an idea gel into a coherent relationship.[26] I like to think of this as those moments when you have a lot of confusion about a concept, but once you understand it, you start to see it everywhere. All of a sudden, all of the facets are brought together and aligned, and you can’t quite remember how you didn’t see it beforehand.

A natural third factor is that these concepts are not self-evident, they are troublesome and take practice to master. Threshold Knowledge is a new mental template of the world, and that only comes with real intellectual work.

Generally this knowledge is seen as irreversible as well and limited, or bounded, meaning there are always new frontiers beyond the horizon of knowledge, new concepts and new schemas to assimilate. [Slide 7]

Slide 7

Conclusion

Personally, I feel that Meyer and Land have given a convenient handle to an important phenomenological event in the learning process, perhaps not too disconnected from the “aha” or “Eureka” moment.[27]

So, then, what might be an example of a Threshold Concept in the field of Religious Studies? I would argue that a prototypical example would be that “religion is a cultural construct.” This is a conceptual threshold that must be crossed in order to understand the modern study of religion. It is not self-evident to non-specialists, and once a person has that shift, they can find the entailments of that insight woven into the fabric of the field.[28] And it is precisely for that fact that I believe this concept should be taught in introductory courses on religion alongside the more stabilized (or normatized) “facts” which form the content of religious literacy.[29] The “critiquing while teaching” approach is successful in achieving a balance between servicing content and critique, and “destabilizing through defining” is but one example of this approach.

In conclusion, scholars of religion are not mere memorizers of facts and we should not treat students in religious studies courses in that manner either. Threshold Concepts mobilize critical thinking in ways that involve analysis, assessment, and creativity with the data. The development of these skills are not only integral to the humanities, but informed civic engagement as well.

Footnotes

[1] Smith 1998.

[2] See, inter alia, Fitzgerald 2000; 2007, Lincoln 1992, Masuzawa 2005, McCutcheon 1997; 2001, Nongbri 2013, and Smith 1978; 1998.

[3] Bell 2006: 30. The creation of “religion” is indebted to comparative Christian theology (e.g. see Masuzawa 2005: 72ff.), or as described by Fitzgerald, “liberal ecumenical theology” (2000: 4-5, 14).

[4] Smith was the first to bring attention to the importance of the taxon of “world religions” (see Smith 1998: 278, Smith 2004: 166-73), but Masuzawa (2005) was integral in outlining its particular European intellectual genealogy. Bell (2006, 2008) then loosely applied the concept of Kuhnian “paradigms,” in as much as they are “scaffolds” for organizing ideas (Bell 2006: 28), of which “World Religions paradigm” was one example (Bell 2006: 34-6). The phrasing was picked up by later scholars such as Suzanne Owen (2011).

Importantly, according to Masuzawa, her primary interest was not to examine the emergence of the Religious Studies field or disciplinary self-consciousness – as is highlighted by Bell and others – but the role world religions played in constructing the “West” (Masuzawa 2005: 10; Masuzawa 2008, esp. 149).

[5] Owen 2011. Bell (2006: 34) also notes the indispensability of the paradigm for teachers.

[6] Owen 2011: 258-9.

[7] To this can be added the presumption of “divine” or “higher” power, as well as the presence of a charismatic religious founder or leader.

[8] See, inter alia, Almond 1988, Schopen 1997, and King 1999. In addition, this conceptualization of religion tends to normatize a literary, and mostly male, elite perspective (Owen 2011: 256, 259).

[9] Owen 2011: 254, 258. This has political ramification outside the classroom as well since normatized conceptions of religions will continue to inform non-specialists in the journalistic and political spheres. (Owen 2011: 260, 261, 266). On a more general level, education in religion will remain an education in comparative morality, whereby abstracted ethical codes that are deemed similar to modern Western Christian morals will be examined (Owen 2011: 266).

[10] Owen’s language seems to vacillate between outright rejection and careful supplementation to the World Religions Paradigm. In her conclusion, Owen suggests that the historical and textual focus in religious studies can be corrected through the incorporation of the social sciences, ethnography specifically (Owen 2011: 256, 265), which can bring it more in line with critical analysis typical in the humanities more broadly (Owen 2011: 257). Thus, it appears her primary concern with the World Religions Paradigm, at the university level, is methodological. (See also her comments on teaching, p. 258, and secondary schools, p. 266). In a later article, Owen suggests a focus on “making sacred” as a corrective to the “world religions” approach (Owen 2016).

[11] Owen 2011: 257, 266. Generally, this framework suggests that there are several discrete religious traditions that all have some implicit resemblance to the Christian model, so much so, as Masuzawa explain, that presumptuously “any broadly value-orienting, ethically inflected viewpoint must derive from a religious heritage” (2005: 20).

[12] Ramey 2016.

[13] Schema Theory was first used to theorize about knowledge and cognition and was borrowed and adapted as a model to understand the processes of learning, notably by Richard Anderson (Anderson, et al.: 1977). There seems to be significant theoretical overlap with Hans-Georg Gadamer’s hermeneutical musings on the “fusion of horizons” (Horizontverschmelzung).

I take Ramey’s point as an important rejection of attempts which radically depart from using vernacular categories or organizational schemas in the classroom that unnecessarily frustrate students (Ramey 2016: 49). I would specifically include here the rather ineffective suggestions – at least in terms of pedagogy – of replacing the word “religion” with “cogmographic formations” (Dubuisson 2003) or “worldviews” (Droogers & van Harskamp 2014).

[14] Ramey 2016: 48. See also the comments of Philip Tite: http://bulletin.equinoxpub.com/2015/08/teaching-beyond-the-world-religions-paradigm/.

[15] Ramey 2016: 51.

[16] I agree with my colleague, Caleb McCarthy, that if insufficient attention is given to describing the purpose of such an exercise, students may reject the values of such a book at all, or question why we even made them purchase it. This critique should be a creative act which seeks to understand the implicit choices all authors or textbooks must make, not a destructive act which renders the work worthless.

[17] See https://www.aarweb.org/about/religious-literacy-guidelines-for-college-students

[18] Indeed the creation and sustenance of a generic “religion” is a practical requirement for the existence of Religious Studies departments, a point made by Smith (1998: 281-2).

[19] See also Ramey 2016: 55.

[20] Flanagan 2016; Land, Rattray & Vivian 2014. In addition, there have been five international conferences on this topic (ibid: xi).

[21] For important connections between Schema Theory and Threshold Comments see Walker 2013.

[22] Meyer & Land 2003: 2.

[23] Walker 2013: 247. Also, “such a transformed view or landscape may represent how people ‘think’ in a particular discipline, or how they perceive, apprehend, or experience particular phenomena within that discipline (or more generally). It might, of course, be argued, in a critical sense, that such transformed understanding leads to a privileged or dominant view and therefore a contestable way of understanding something. This would give rise to discussion of how threshold concepts come to be identified and prioritised in the first instance” (Meyer & Land 2003: 1).

[24] Land, Meyer & Flanagan 2016: xii.

[25] Land, Meyer & Flanagan 2016: xxiii and elsewhere in this volume.

[26] Land, Meyer & Flanagan 2016: xii.

[27] To my knowledge there has been no serious attempt at correlating the two.

[28] Of course, from certain theological or even comparative phenomenological frameworks the idea that the category of religion is a cultural construct is anathema, or to use a playful analogue, heretical. From another perspective, Jason Davies (2016) points to the tribalism sometimes encountered in academic circles who try to keep the doors closed to their disciplines, terming this “threshold guardianship.”

[29] In breaching the Threshold Concept that “religion is a construct,” students become “insiders” of the discipline. This is in contrast to being or becoming an insider to a religion (in as much as one doesn’t define religion to include academic disciplines, but this is of course entirely possible!). Ever since Religious Studies was wrenched from Theology departments there seems to have emerged a lingering question as to how to preferably teach religious studies. A clear distinction is made between prescriptive (or confessional) statements, which belong to the field of Theology, and descriptive or analytical statements, which fall under the purview of Religious Studies. Yet, the level to which students inhabit those descriptions and analyses manifests on a sliding scale. An interesting discussion that moves in this direction is offered by Gerald Larson, who, borrowing from Melford Spiro, distinguishes between “acculturation” and “enculturation.” Acculturation in this context means to acquire propositions about a religion, while enculturation requires a level of internalization to the degree that they might become true or right (Larson 1988: 203). One reading of this would equate enculturation with Theologically prescriptive statements, but I think another reading is possible whereby enculturation could signal the “trying out” of perspectives without accepting them as totalizing truths. At some level, I think this is why meditation (typically Buddhist) is sometimes “practiced” in religious studies classrooms, in order to potentially capitalize on the affective components of deeper learning experiences, but not quite breaching the status of being prescriptive (this also explains why some are bothered by such exercises). This affective component I would argue plays a seminal role in the classes of Michael Puett, a popular professor of Chinese philosophy at Harvard University, who claims his courses will “change your life” (See https://theatln.tc/2o1IvPU). Of course, if he were a professor of Chinese religion, the claim may take a different, potentially problematic, coloring. This seems to be an interesting issue at the heart of a liberal arts educations which moves toward “character formation”; it is embraced unless there is the possibility of a “religious” tinge to it (see e.g. the comments by Owen 2011: 265-6). This struggle is also embodied in Ninian Smart’s dictum that the phenomenology of religion be guided by both époche (suspension or bracketing) and informed empathy. Nevertheless, the concern of making lecture material meaningful is mostly aligned with making it register on an affective level with the student. Since Threshold Concepts represent “troublesome knowledge,” the process of acquiring and integrating them is also noted for its affective quality, though these are truths bounded by disciplinary discourse (see, e.g. Walker 2013).

Bibliography

Almond, Philip. 1988. The British Discovery of Buddhism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, R.C. et al. 1977. “Frameworks for Comprehending Discourse,” American Educational Research Journal, Vol 14, No. 4, pp. 367-81.

Bell, Catherine. 2006. “Paradigms behind (And before) the Modern Concept of Religion,” History and Theory, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 27-46.

Bell, Catherine. 2008. “Extracting the Paradigm-Ouch!” Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, Vol. 20, pp. 114-24. [Review of Masuzawa’s thesis

Droogers, André and Anton van Harskamp, eds. 2014. Methods for the Study of Religious Change: From Religious Studies to Worldview Studies. Sheffield: Equinox.

Dubuisson, Daniel. 2003. The Western Construction of Religion: Myths, Knowledge, and Ideology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fitzgerald, Timothy. 2000. The Ideology of Religious Studies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fitzgerald, Timothy. 2007. Religion and the Secular: Historical and Colonial Formations. New York: Routledge.

Flanagan, M. 2016. Threshold Concepts: Undergraduate Teaching, Postgraduate Training and Professional Development: A Short Introduction and Bibliography. London: UCL. Retrieved from http://www.ee.ucl.ac.uk/~mflanaga/thresholds.html

Gearon, Liam. 2014. “The Paradigms of Contemporary Religious Education,” Journal for the Study of Religion, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 52-81.

King, Richard. 1999. Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India, and “the Mystic East.” New York: Routledge.

Land, Ray, Jan Meyer, and Michael Flanagan, eds. 2014. Threshold Concepts in Practice. Rotterdam: Sense Publishing.

Larson, Gerald. 1988. “An Introduction to the Santa Barbara Colloquy: Some Unresolved Questions,” Sounding: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 71, No. 2-3, pp. 187-204.

Lincoln, Bruce. 1992. Discourse and the Construction of Society: Comparative Studies of Myth, Ritual, and Classification. New York: Oxford University Press.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. 2005. The Invention of World Religions: or, How European Universalism was preserved in the Language of Pluralism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. 2008. “What Do the Critics Want?—A Brief Reflection on the Difference between a Disciplinary History and a Discourse Analysis,” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 139-49.

McCutcheon, Russell T. 1997. Manufacturing Religion: The Discourse on Sui Generis Religion and the Politics of Nostalgia. New York: Oxford University Press.

McCutcheon, Russell T. 2001. Critics Not Caretakers: Redescribing the Public Study of Religion. Albany: SUNY Press.

Meyer, Jan and Ray Land. 2003. Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practicing in the Disciplines. ETL Project Occasional Report.

Nongbri, Brent. 2013. Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Owen, Suzanne. 2011. “The World Religions Paradigm: Time for a Change,” Arts & Humanities in Higher Education, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 253-68.

Ramey, Steven. 2016. “The Critical Embrace: Teaching the World Religions Paradigm as Data,” in After World Religions: Reconstructing Religious Studies, Christopher R. Cotter and David G. Robertson, eds., New York: Routledge, pp. 48-60.

Schopen, Gregory. 1997. “Archaeology and Protestant Presuppositions in the Study of Indian Buddhism,” History of Religions, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp.1-23.

Smith, Jonathan Z. 1978. Map is Not Territory: Studies in the History of Religion. Leiden: Brill.

Smith, Jonathan Z. 1998. “Religion, Religions, Religious,” in M.C. Taylor, ed., Critical Terms of Religious Studies, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 269-84.

Smith, Jonathan Z. 2004. Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Walker, Guy. 2013. “A Cognitive Approach to Threshold Concepts,” Higher Education, Vol. 65, No. 2, pp. 247-63.

![In Defense of Lectures? [Part II]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/lecture-ii-banner-romaskiewicz.jpg?w=662)

![In Defense of Lectures? [Part I]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/lecture-i-banner-romaskiewicz.jpg?w=662)

![How Does One Do “Religious Studies”? Religious Studies Paradigms [Part III]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/rs-banner-romaskiewicz.jpg?w=662)

![How Does One Do “Religious Studies”? Religious Studies and Humanities [Part II]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/rs-banner-romaskiewicz-1.jpg?w=662)

During our first class meeting, these ideas are approached through conversation with my students about why they are taking my class (I’ve yet to have a religious studies major in any of my classes; I’m lucky if I have anyone whose major is in the humanities!). Typically, after listening to several comments on how this class fulfills several requirements, I begin to ask slightly more probing questions: Why this class? (Surely other classes fulfilled these requirements too!) Undoubtedly, a few start to open up about personal interests or express their genuine curiosity. I use those insights to propel discussion about the potential value of Religious Studies classes and how students can approach our class. For this summer class, I then introduced them to the three levels of aspiration (above) and asked them where they thought they might fall in the spectrum.

During our first class meeting, these ideas are approached through conversation with my students about why they are taking my class (I’ve yet to have a religious studies major in any of my classes; I’m lucky if I have anyone whose major is in the humanities!). Typically, after listening to several comments on how this class fulfills several requirements, I begin to ask slightly more probing questions: Why this class? (Surely other classes fulfilled these requirements too!) Undoubtedly, a few start to open up about personal interests or express their genuine curiosity. I use those insights to propel discussion about the potential value of Religious Studies classes and how students can approach our class. For this summer class, I then introduced them to the three levels of aspiration (above) and asked them where they thought they might fall in the spectrum.