For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

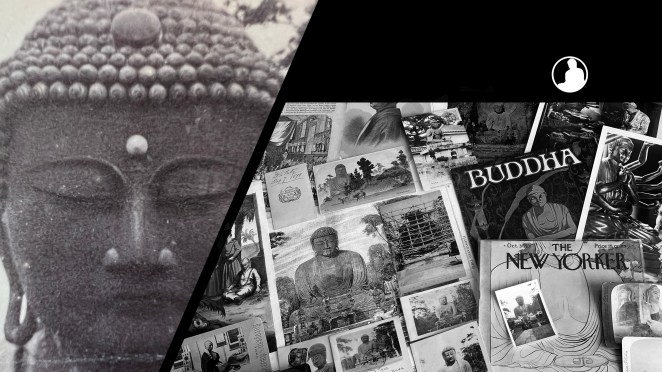

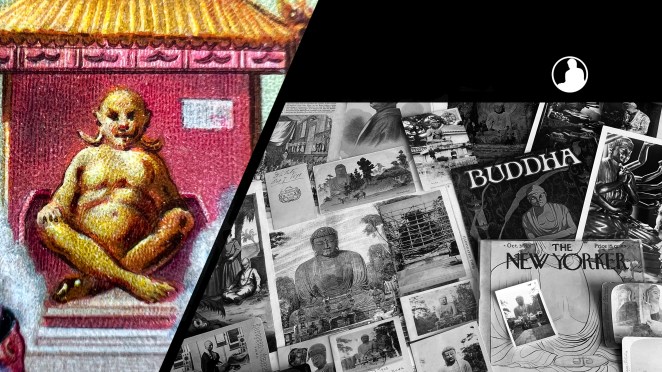

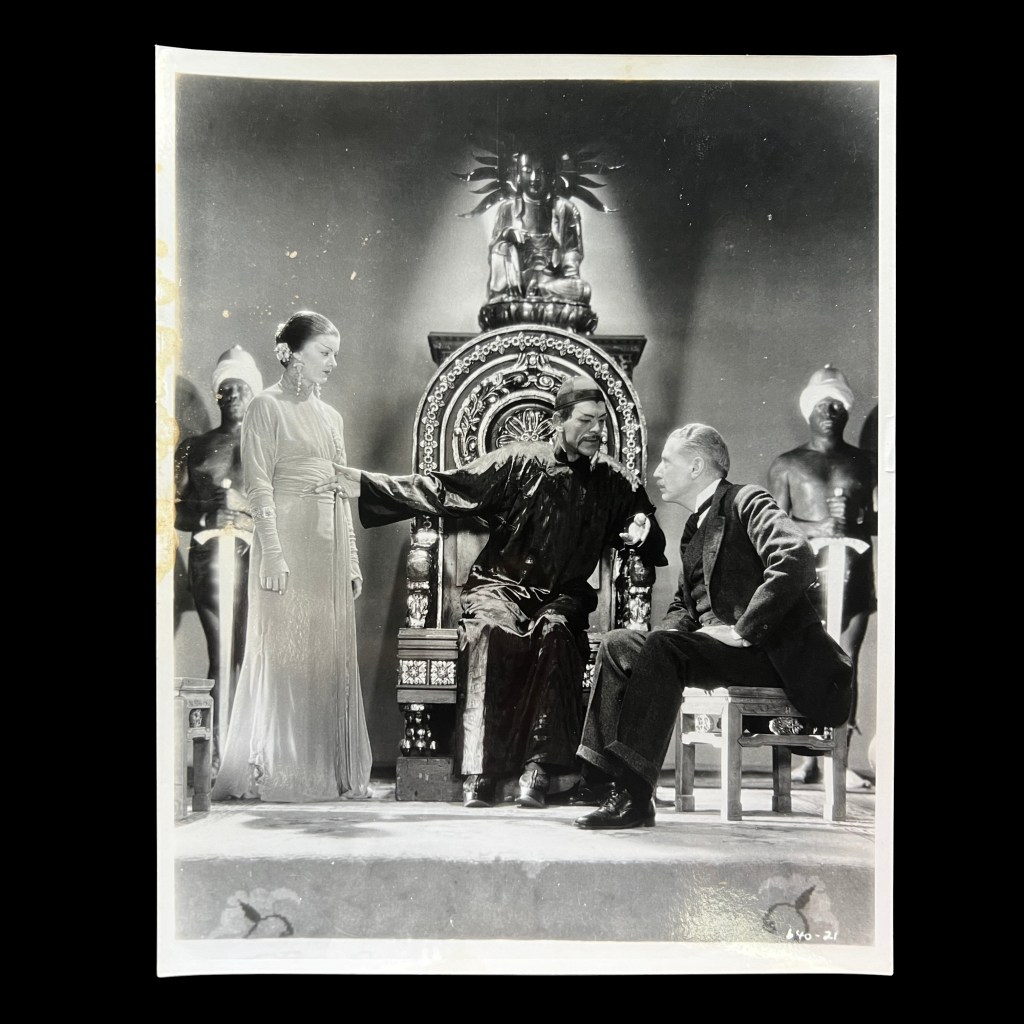

Fu Manchu’s opulent Gobi Desert lair seen in The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932) was assembled by MGM art director Cedric Gibbons. While the Art Deco inspired torture chambers remain horror classics, Gibbons’ strategic use of Buddhist statuary also hint to the audience impending danger.

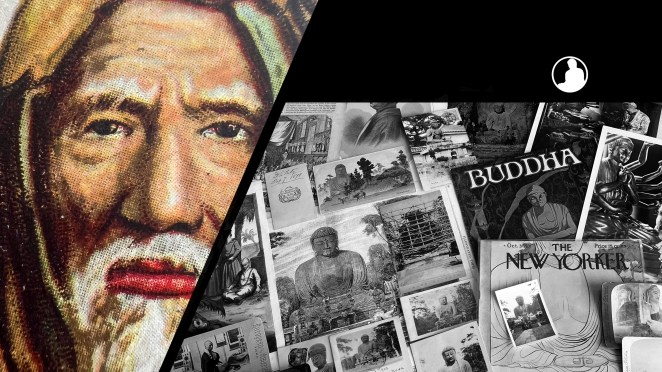

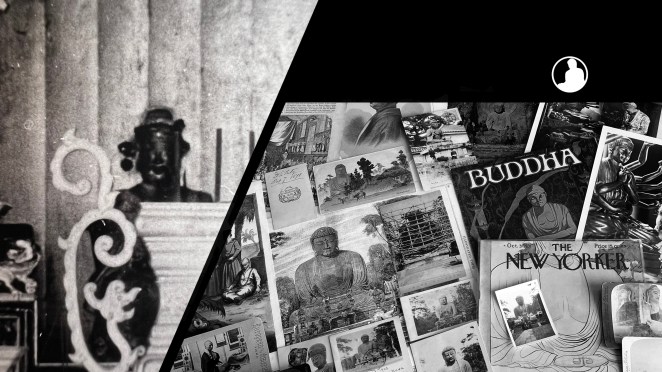

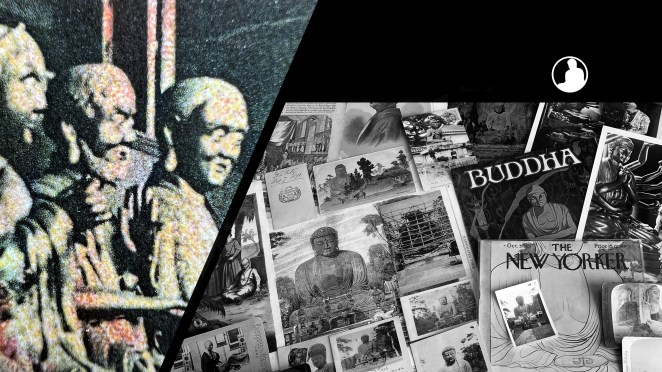

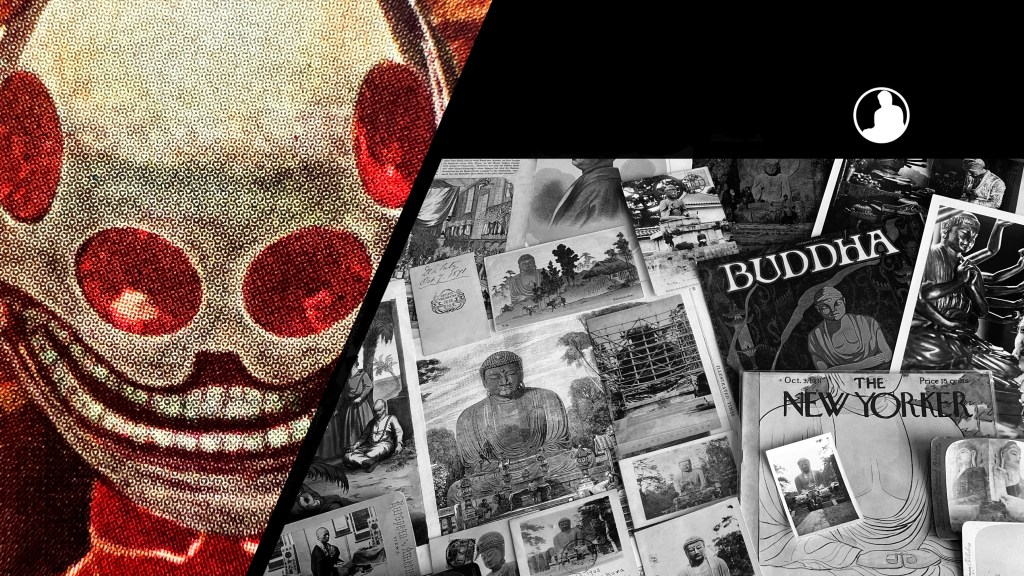

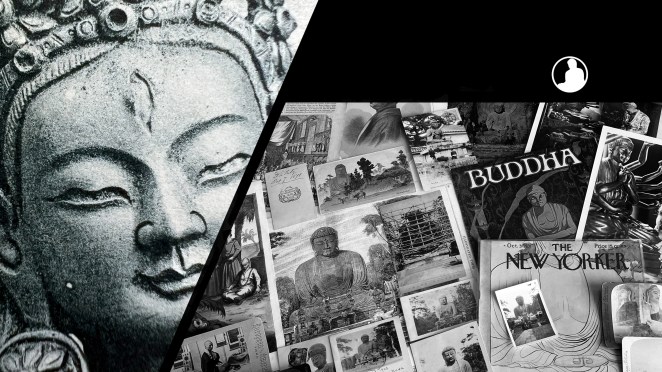

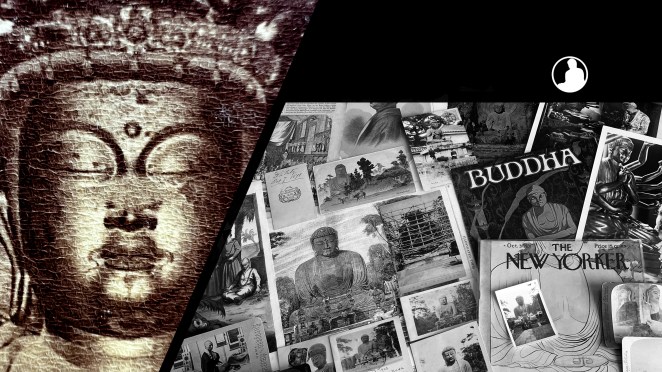

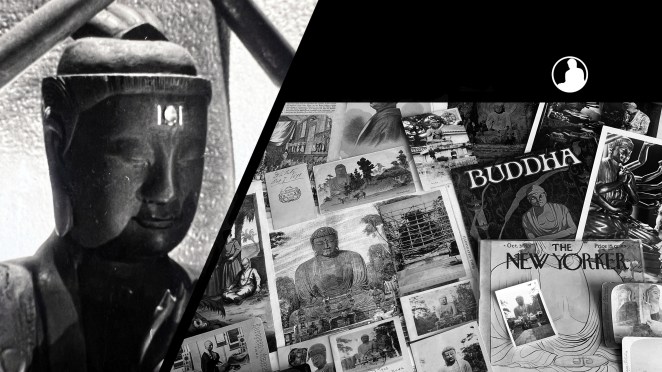

Boris Karloff portrayed the villainous doctor Fu Manchu, here sitting on a throne introducing his daughter Fah Lo See (Myrna Loy). This scene unfolds under the eyes of a shadowy Buddhist figure perched atop the throne; close inspection reveals this to be in the style of a Guanyin statue.

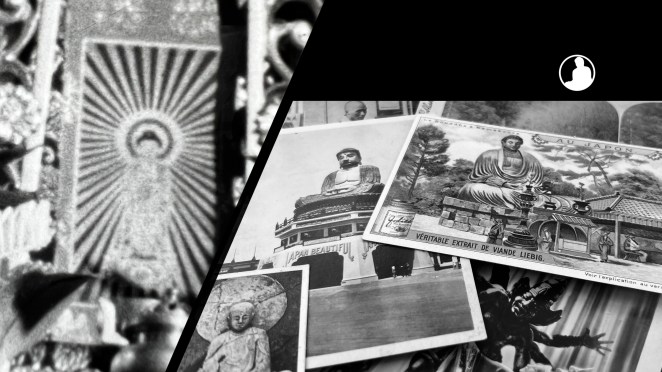

Many props Gibbons used were made at the studio, including some of the Buddhist statues seen on screen. The idiosyncratic elements, including the multi-rayed halo, suggested this statue was pieced together by set designers; it was seen previously in Daughter of the Dragon (1931).

Curiously, the ornate backrest of the throne makes it appear as if Fu Manchu himself is a statue encircled by a halo. Like a menacing statue come to life, the audience can surmise the visitor will suffer at the hands of the villain.

Fu Manchu played on the racist fears of the Yellow Peril; in film, these fears could also be signified by Buddhist imagery. For further discussion of the dueling positive and negative views of China in American cinema, see Naomi Greene’s From Fu Manchu to Kung Fu Panda (2014).

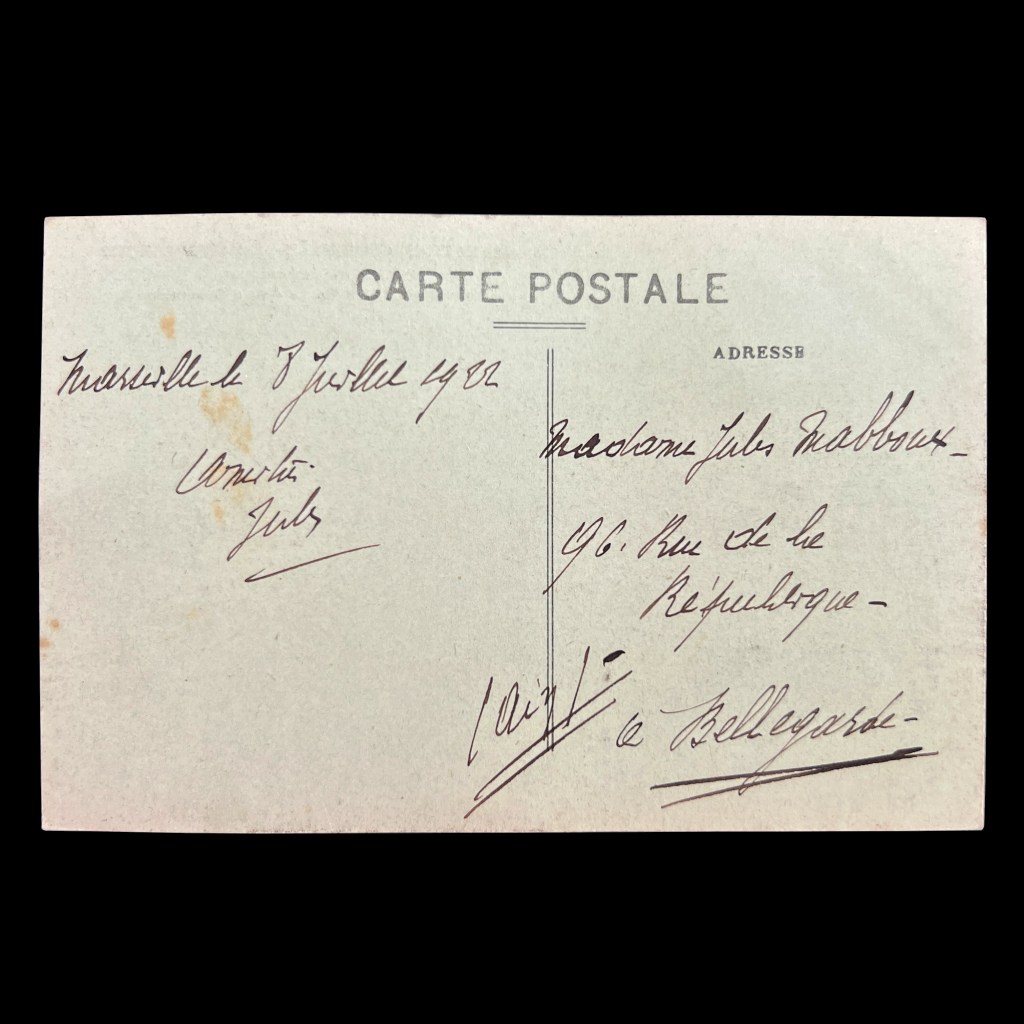

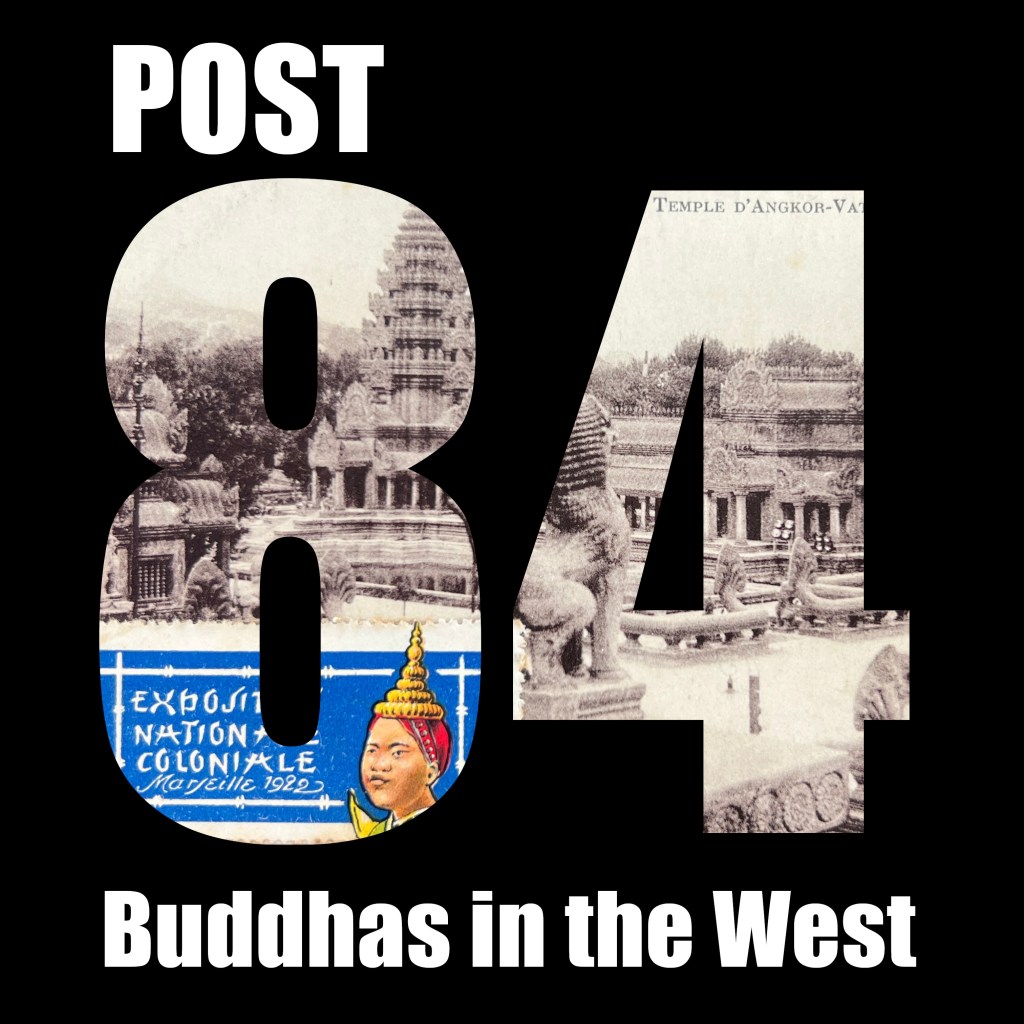

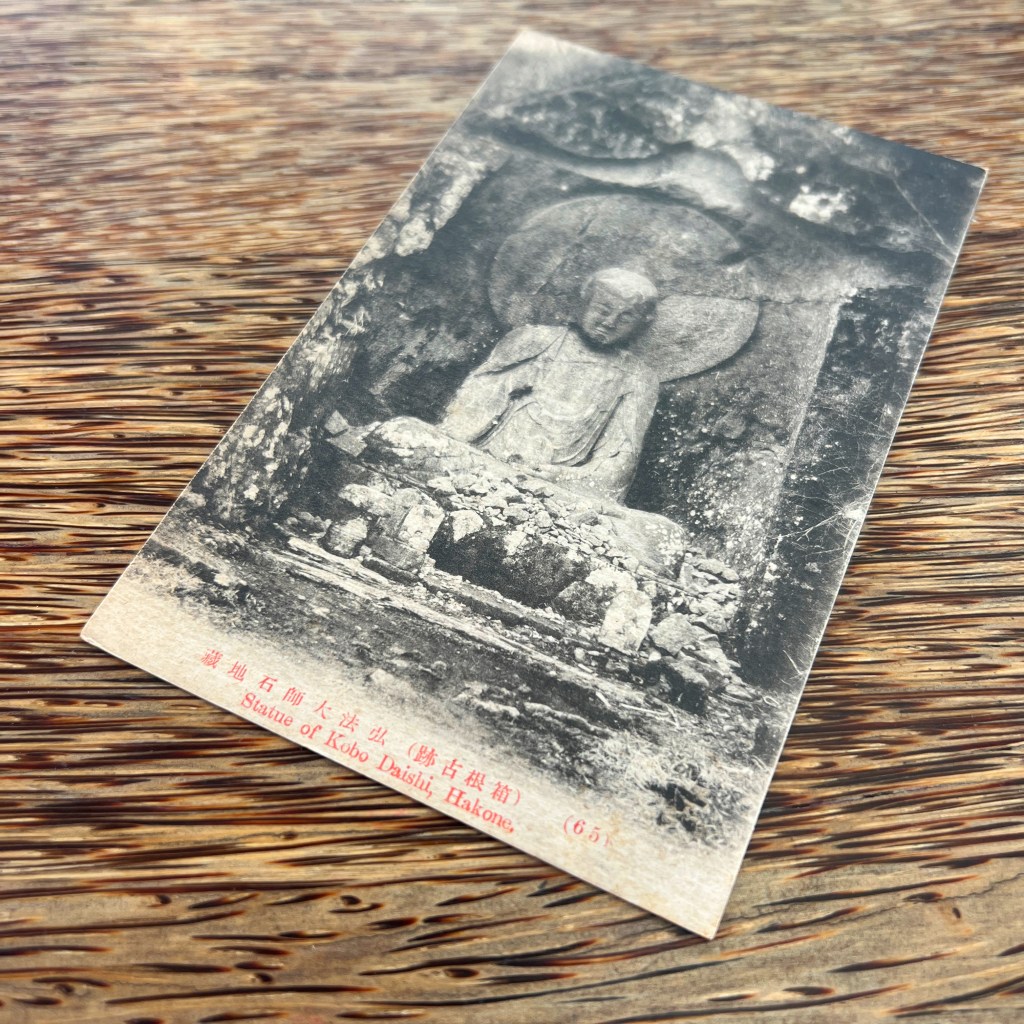

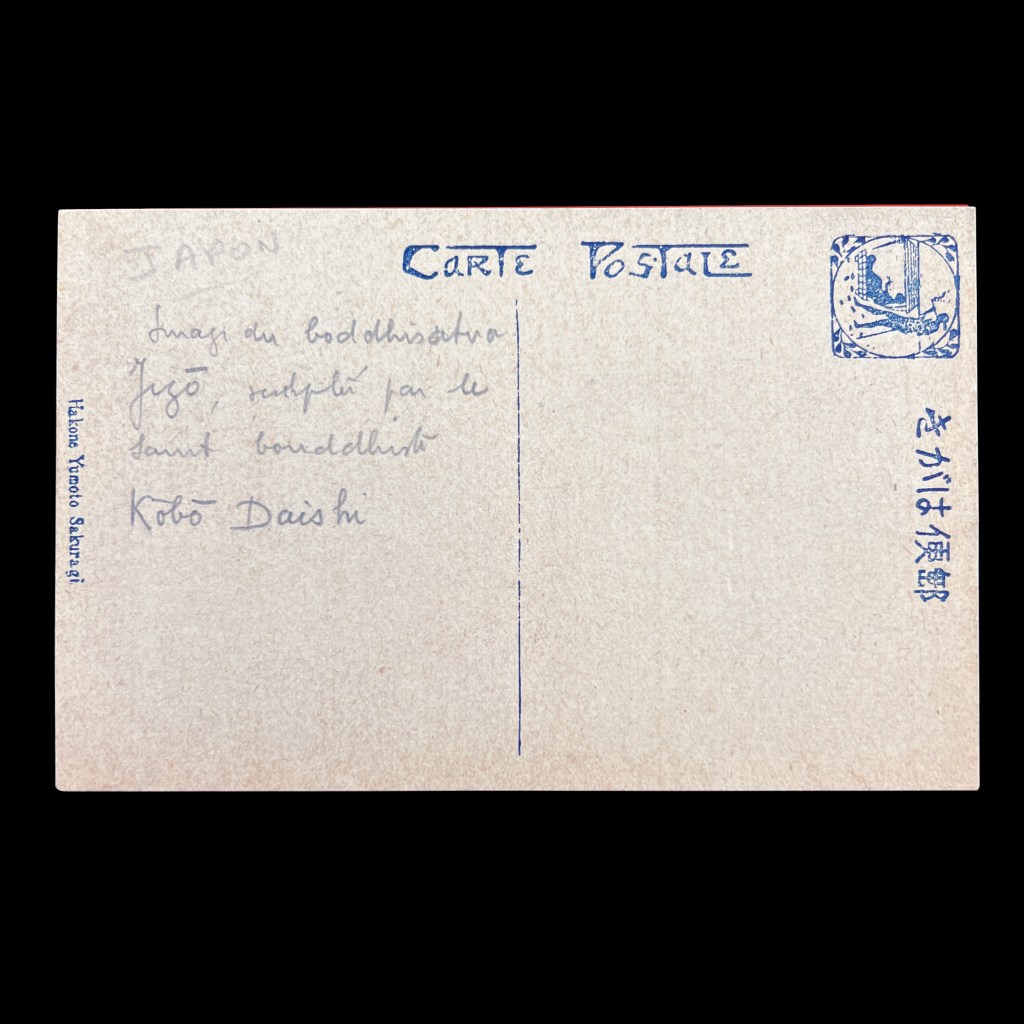

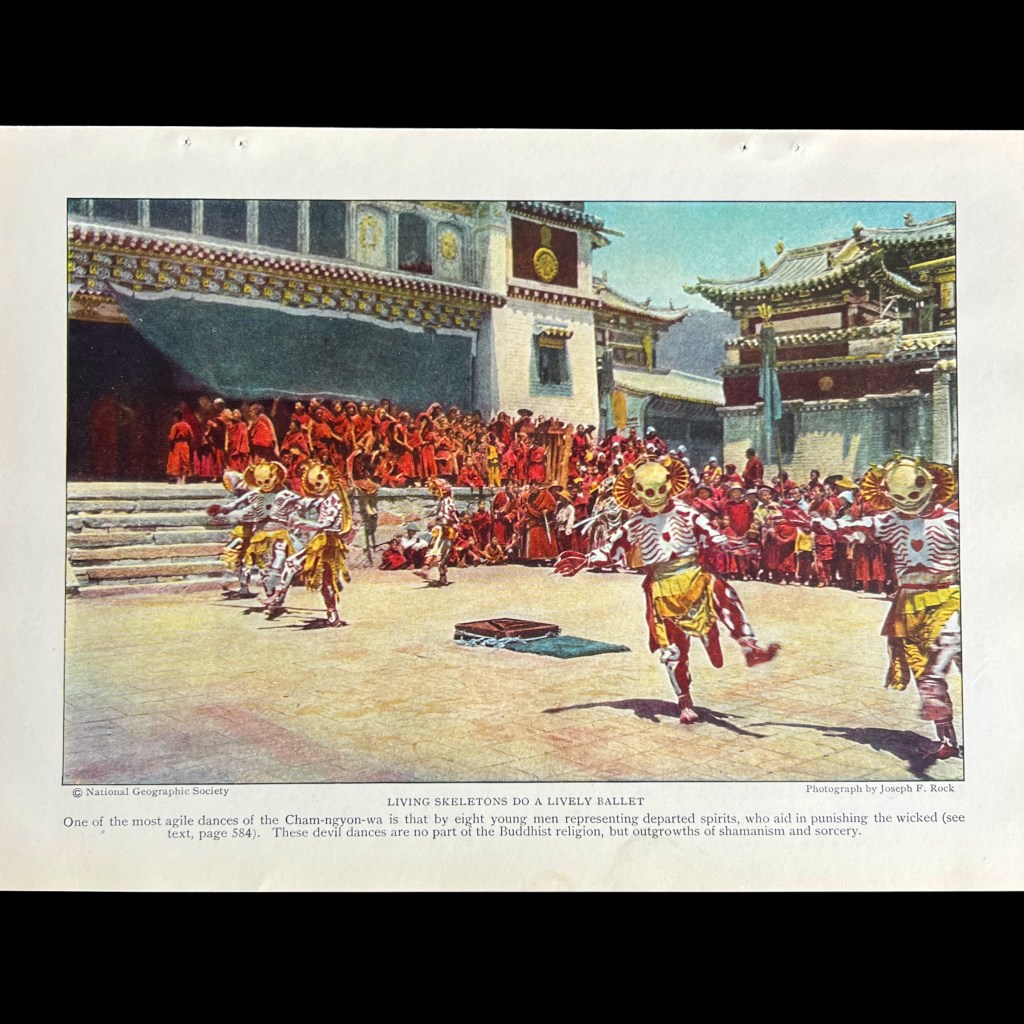

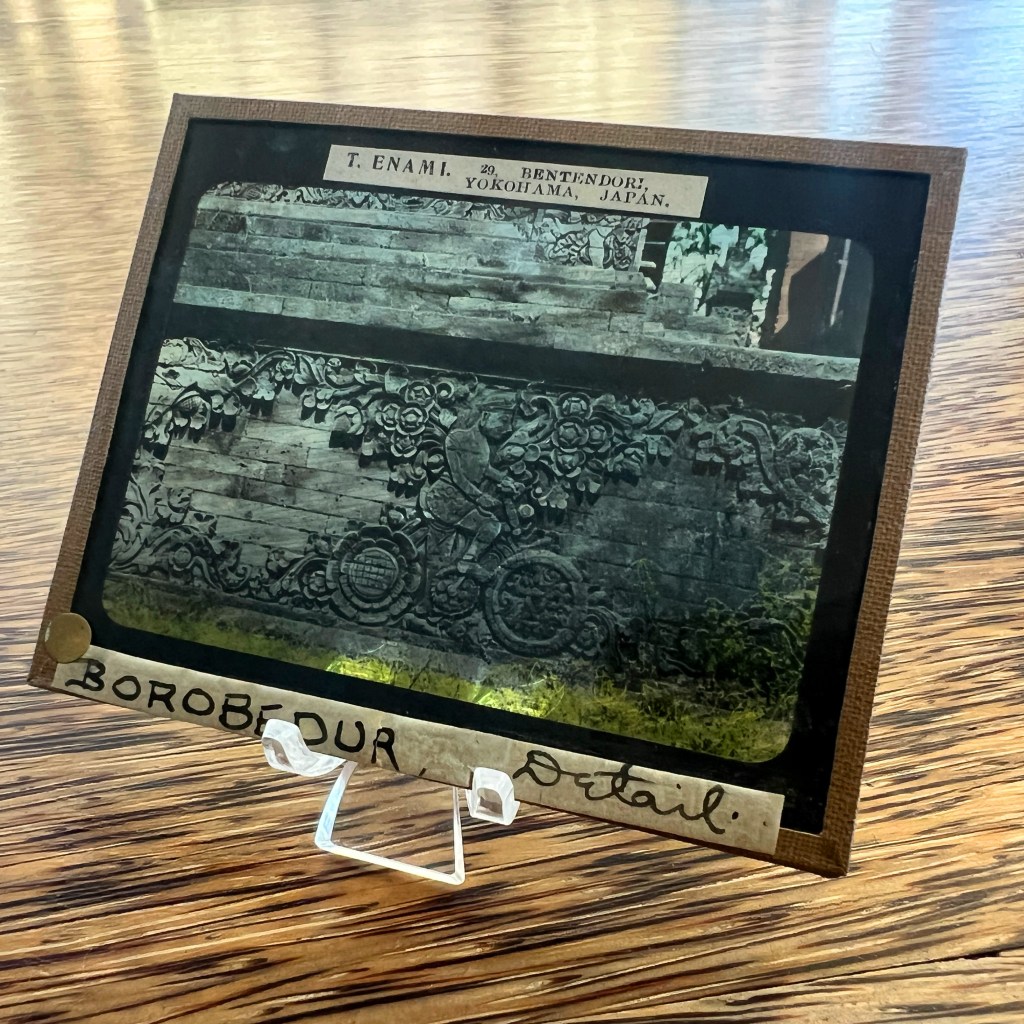

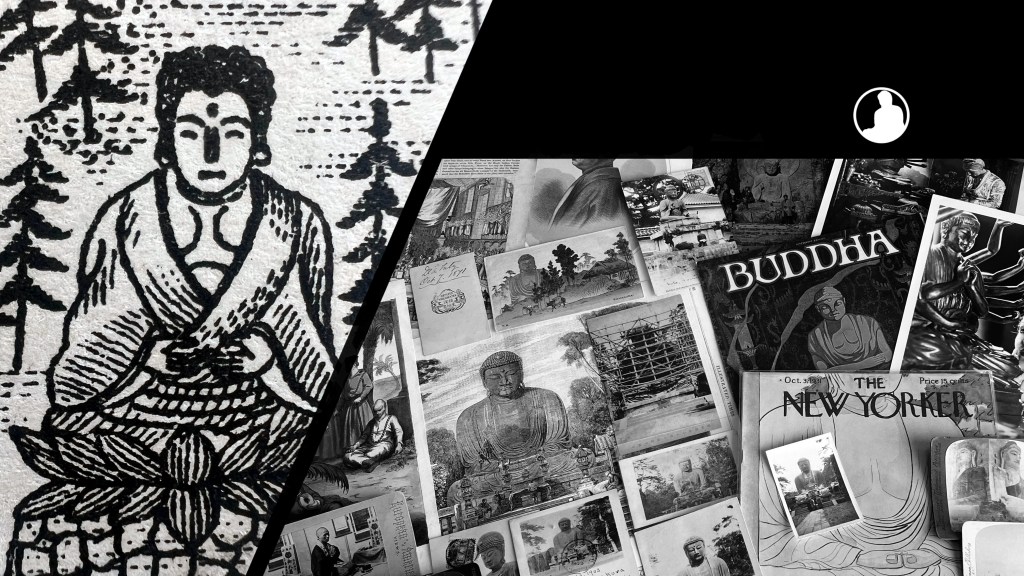

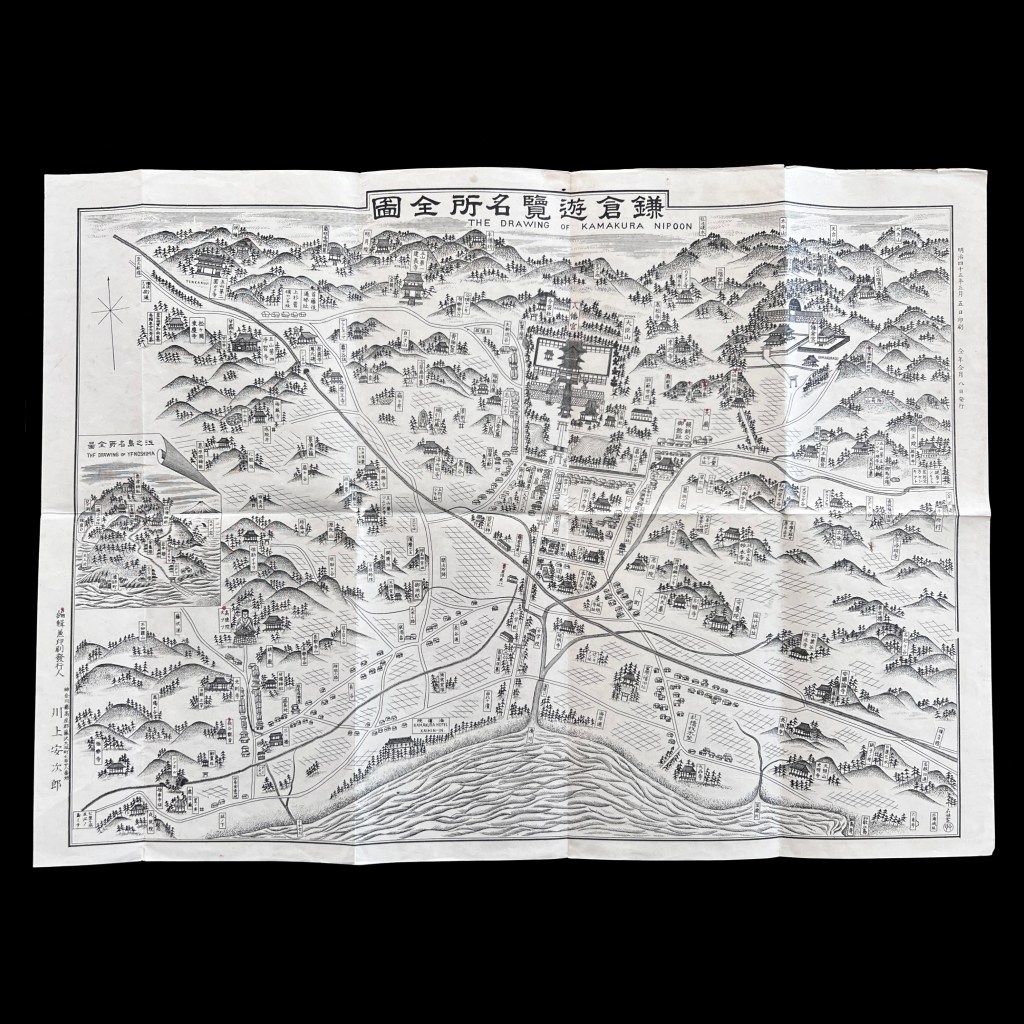

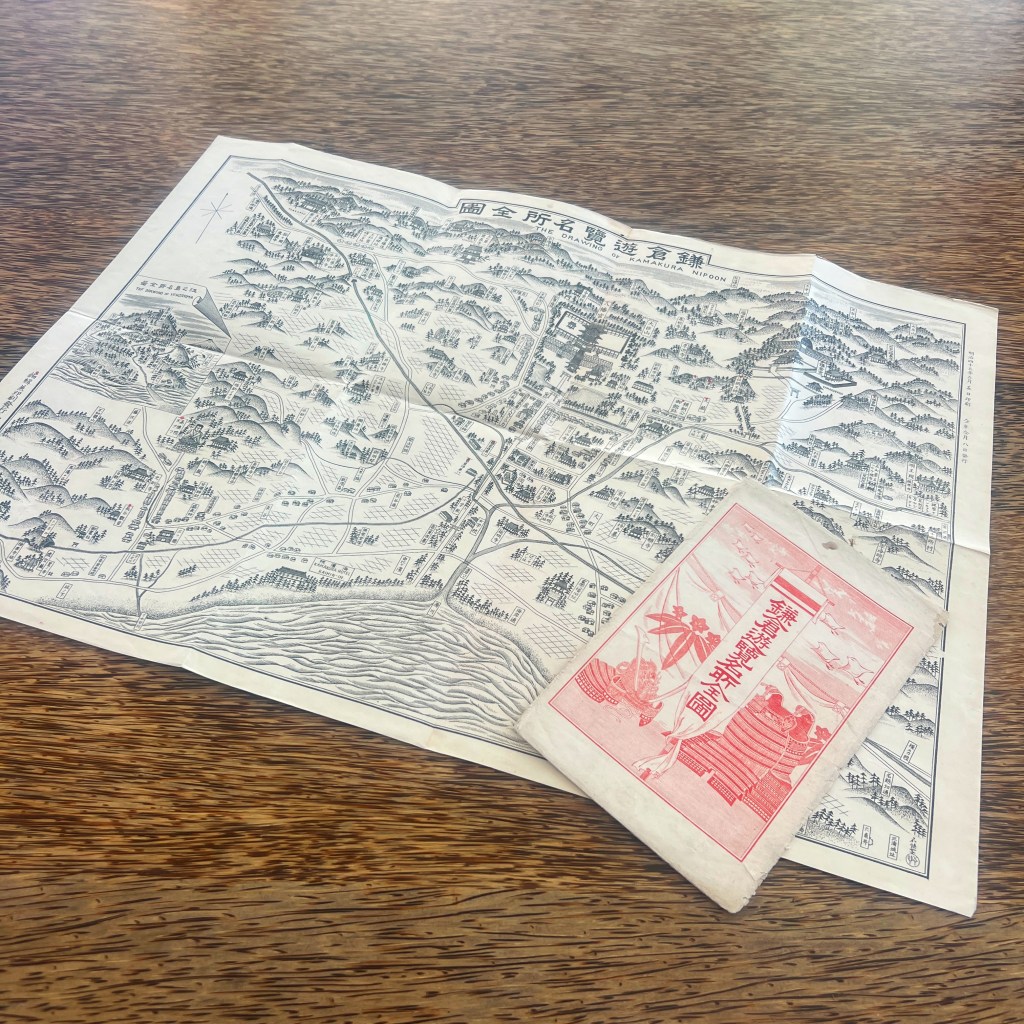

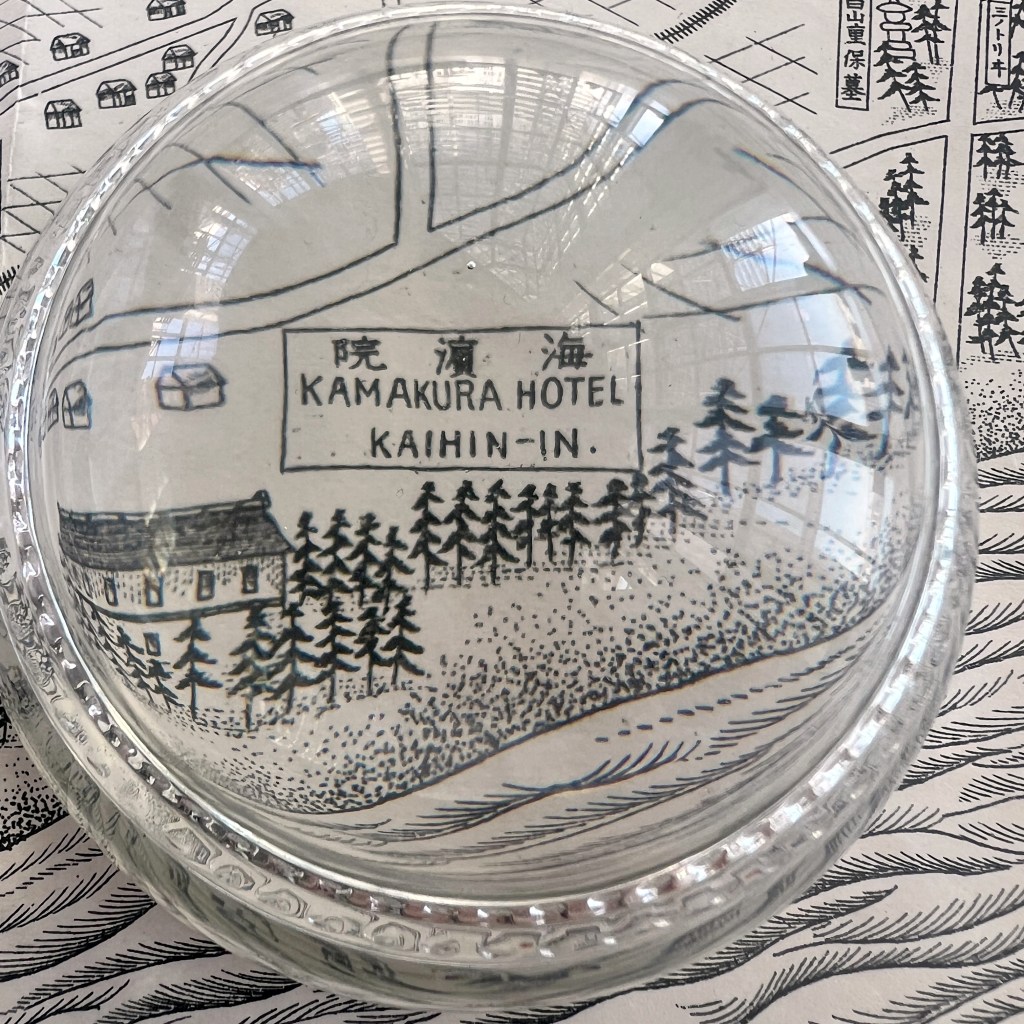

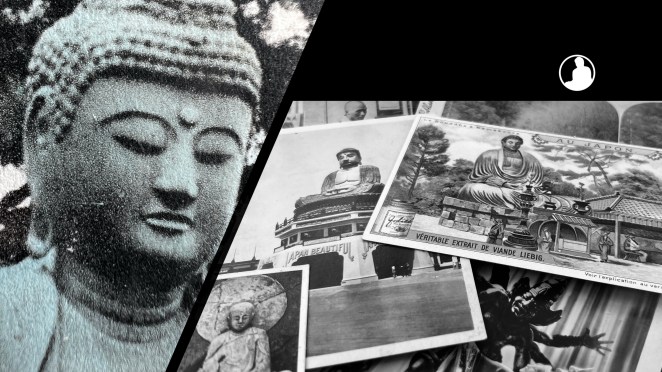

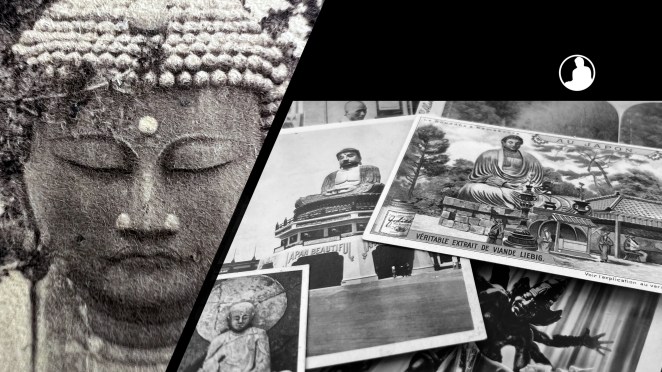

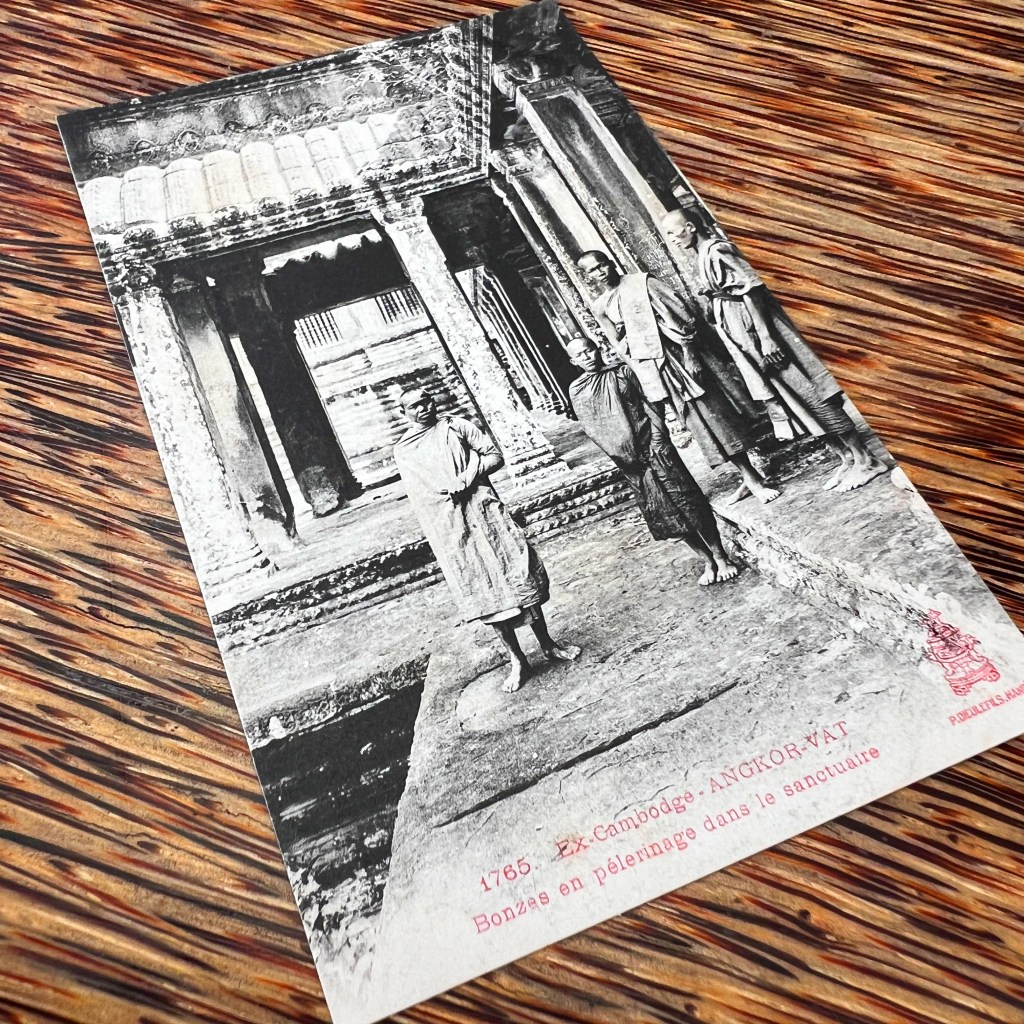

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Guanyin / Avalokiteśvara:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: