For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

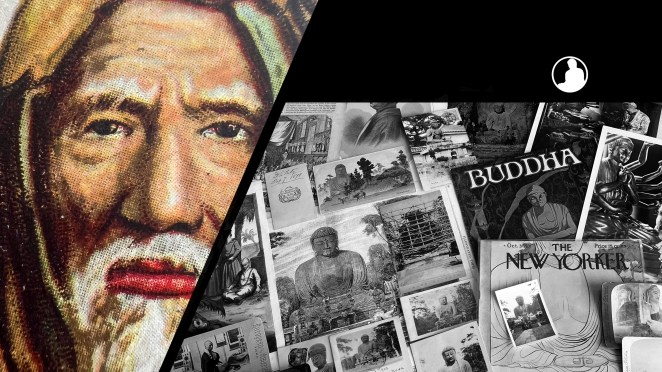

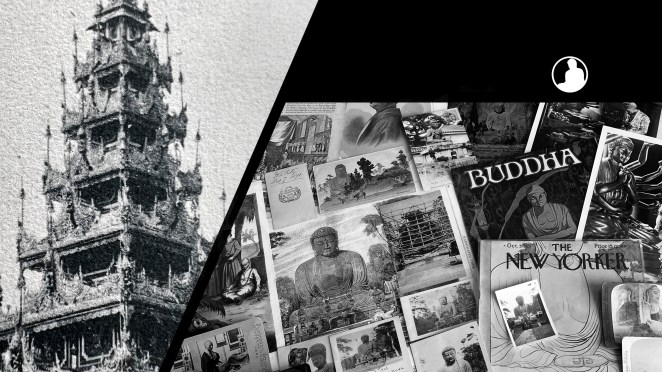

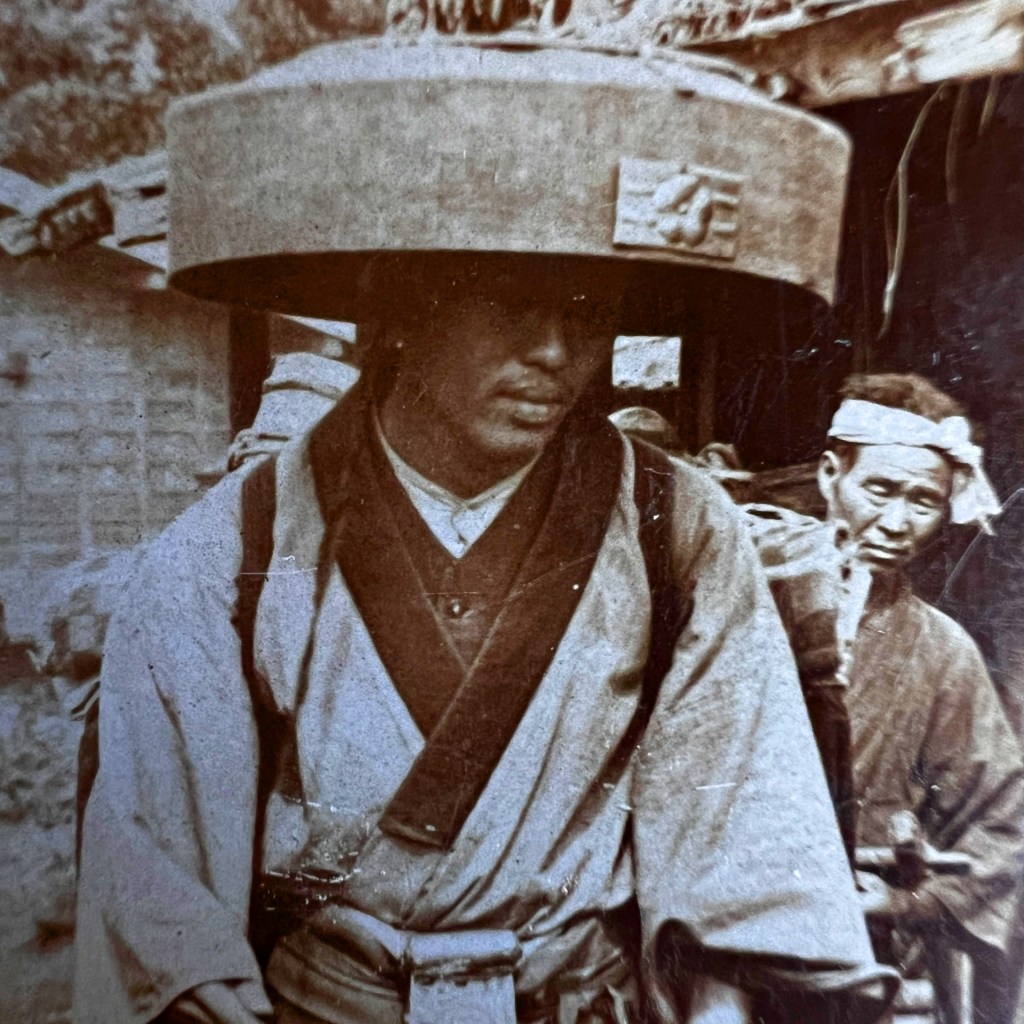

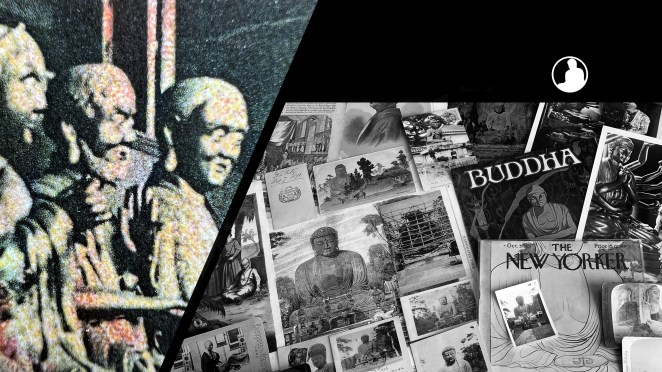

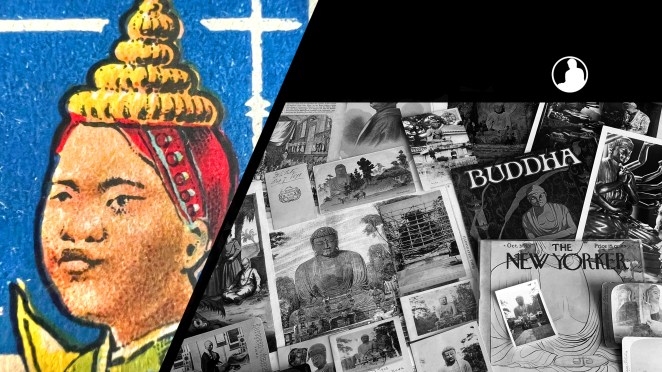

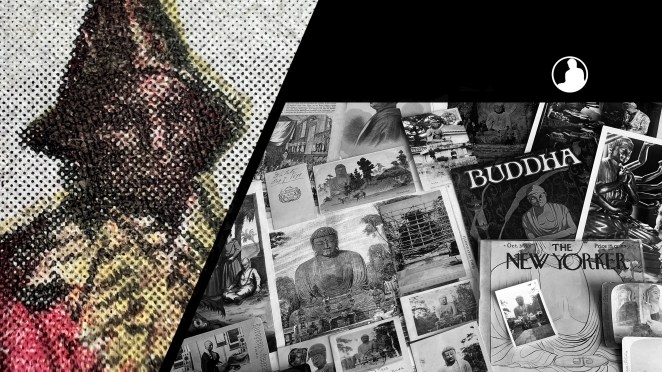

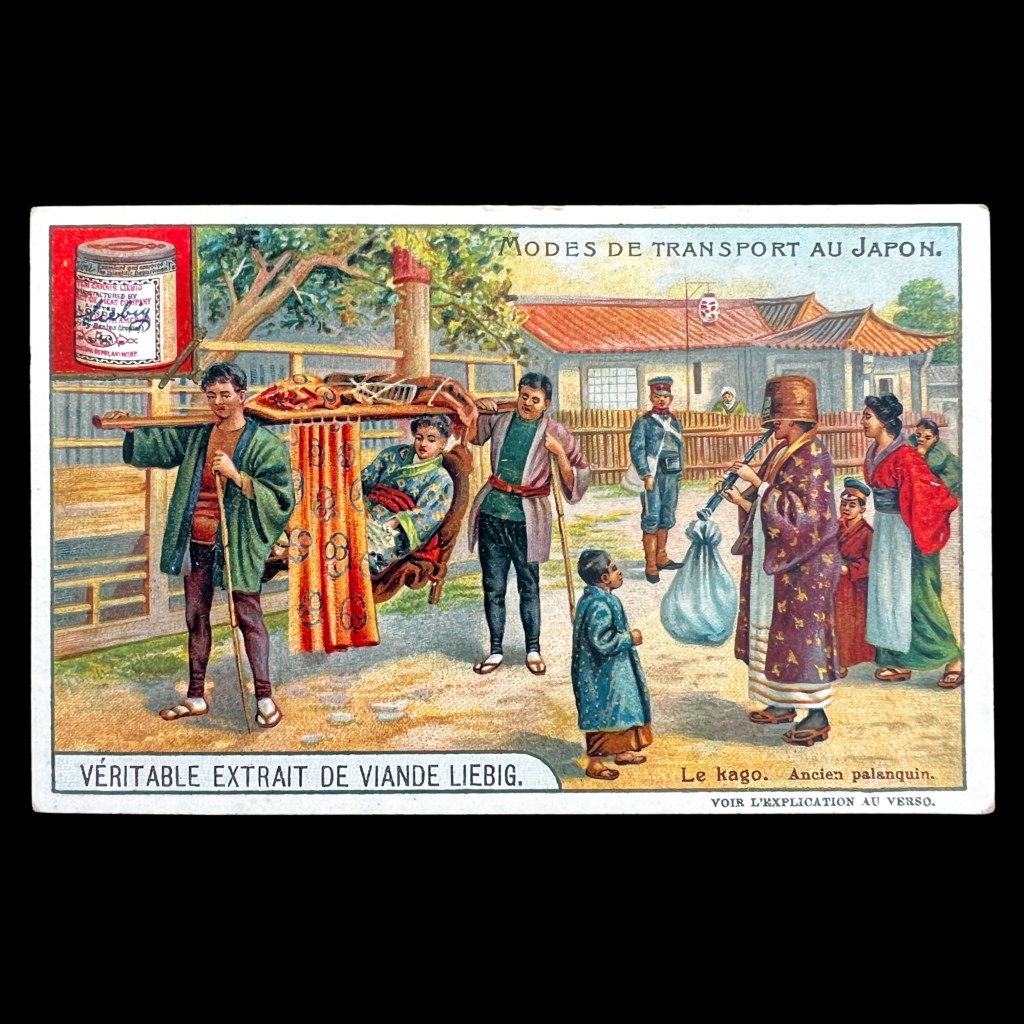

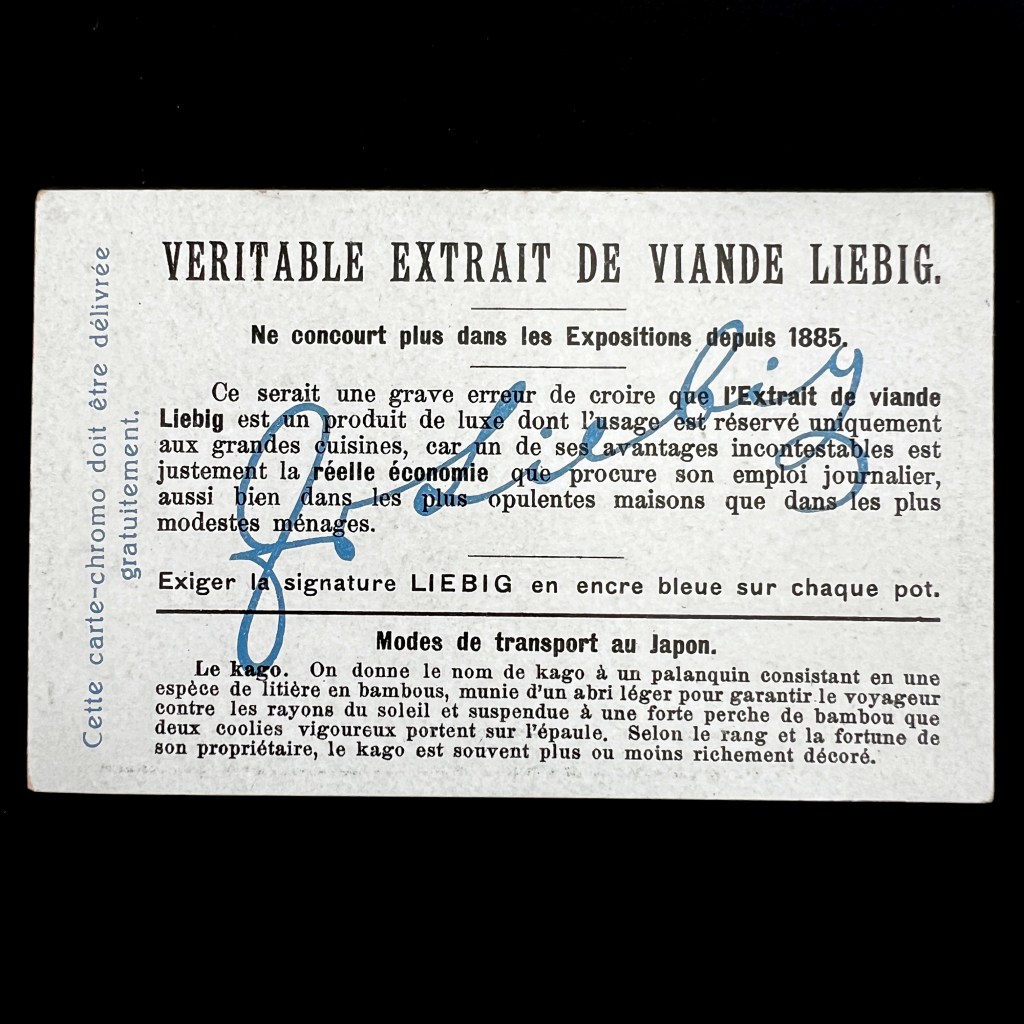

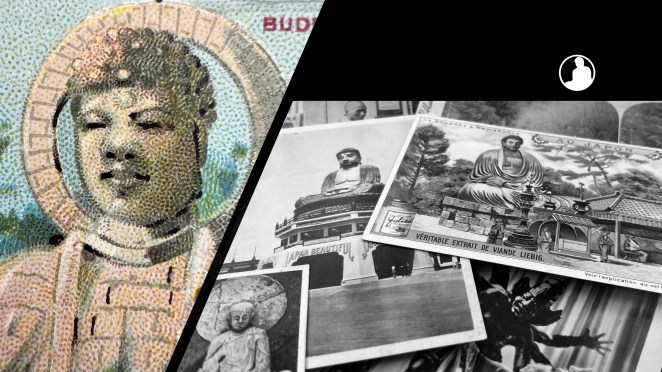

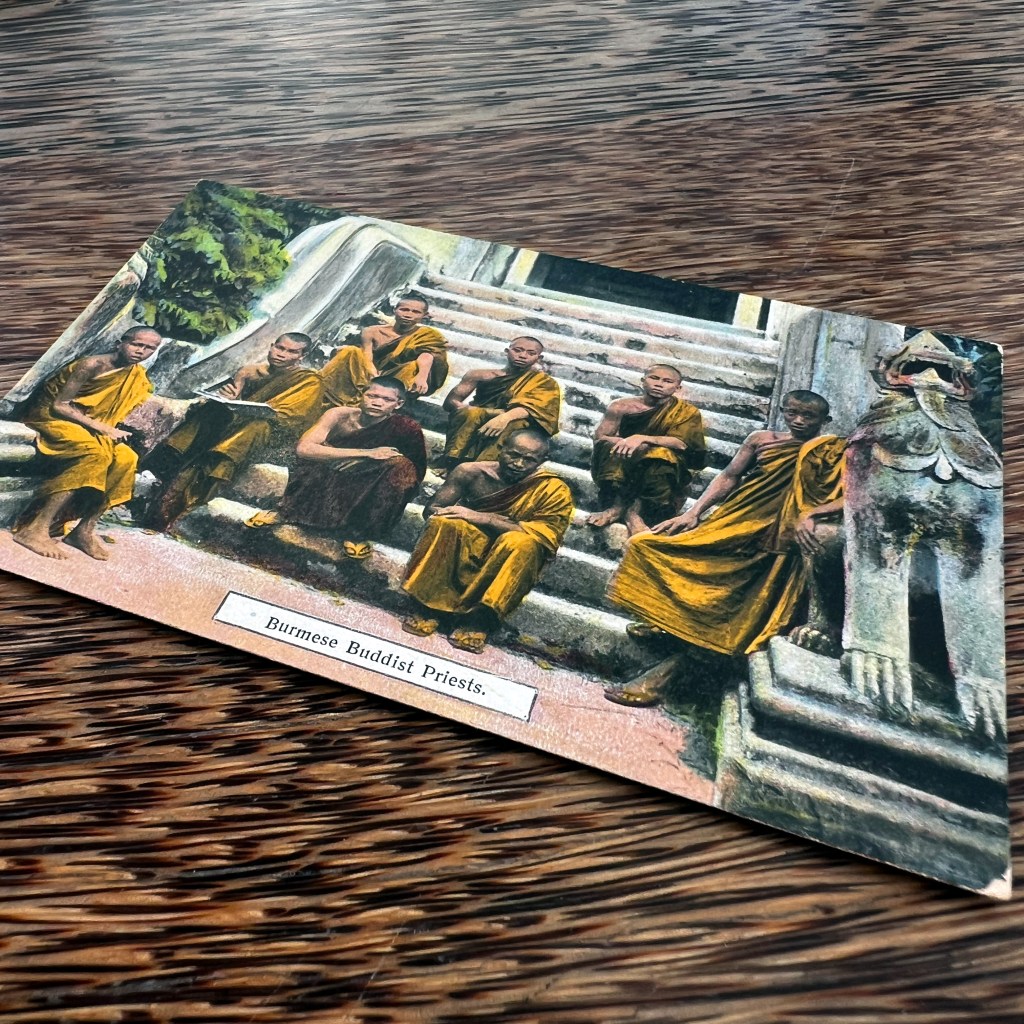

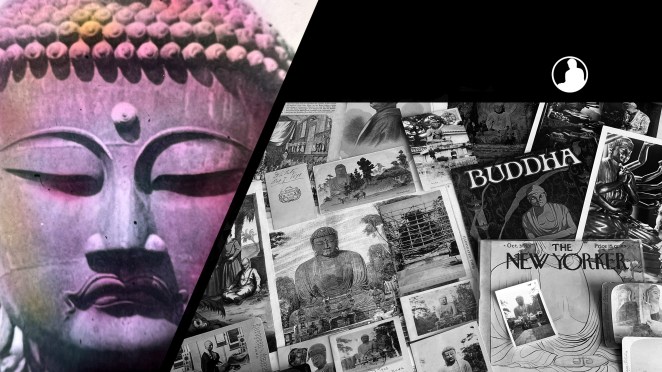

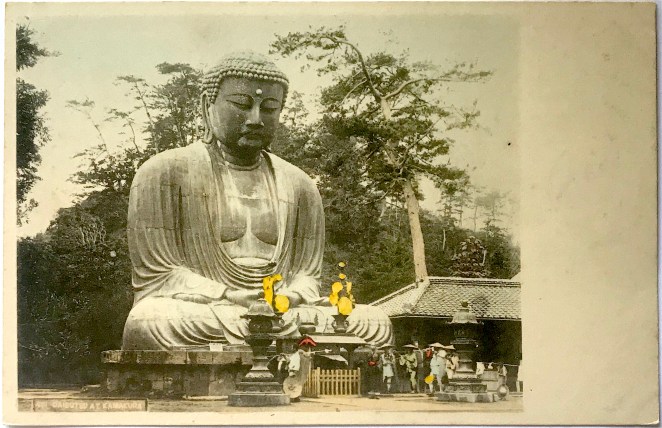

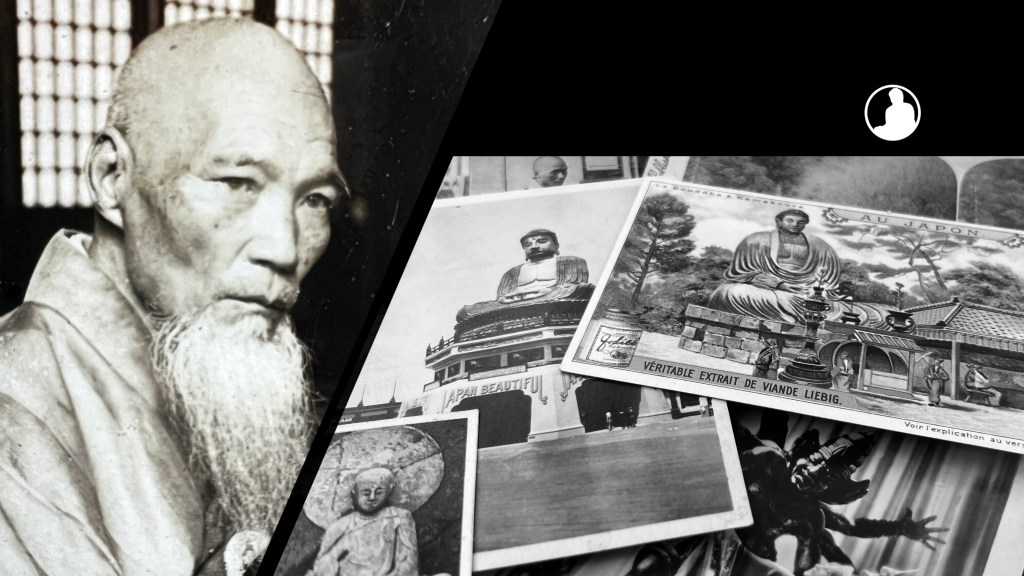

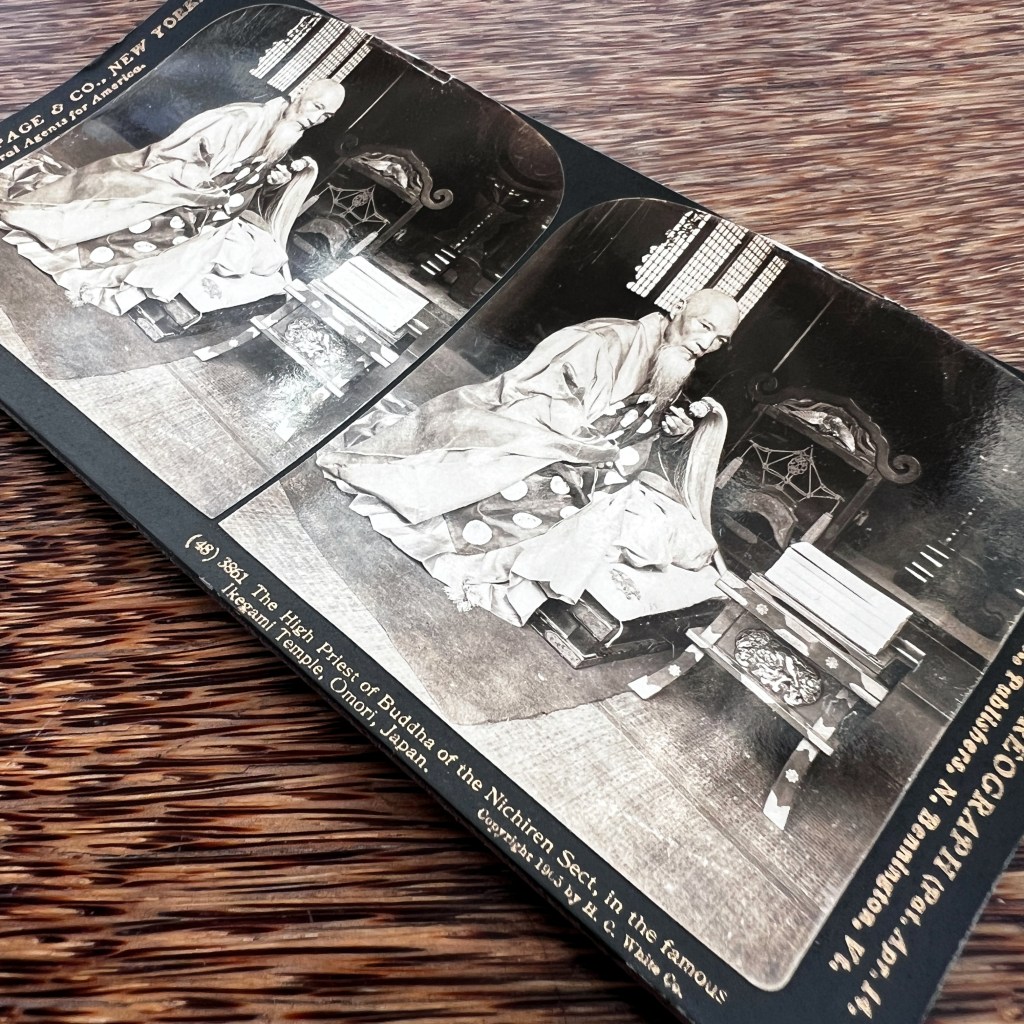

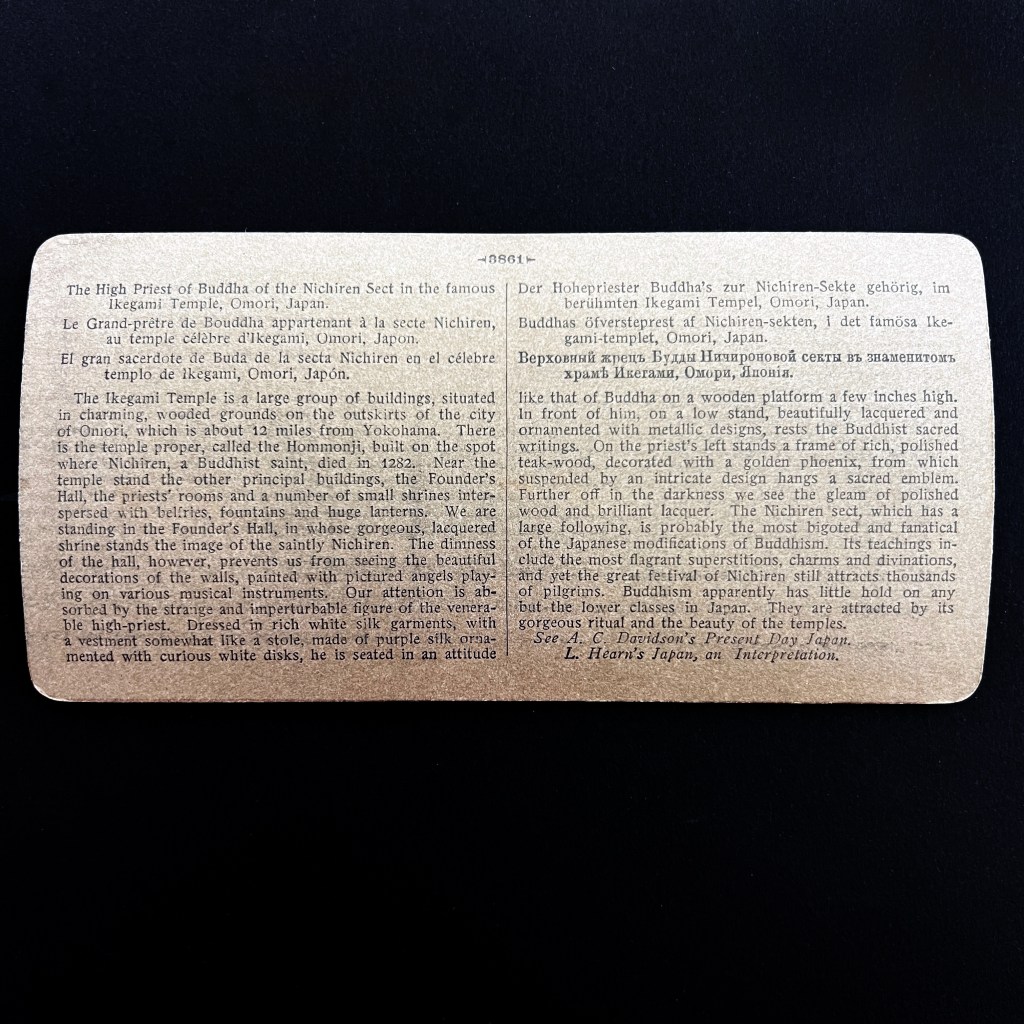

At the turn of the twentieth century, photographer D. A. Ahuja was integral in creating a visual canon of British colonial Burma. His picture postcards were among the most reprinted images of the era, including this portrait of an unnamed “Burmese priest.”

The image was made by a lithographic-halftone hybrid process, whereby a black halftone screen was applied on top of a multi-color lithographic substrate. The “divided back” design suggests Ahuja printed this card around 1910.

Burmese pagodas and monks were common enough to warrant claiming they constituted their own visual genre of “Burmese religious life.” The colorist here inaccurately represented the monk’s robes, combining the two most common colorways – saffron and maroon – into one.

Somewhat unique to his oeuvre, Ahuja photographs his subject in formal portraiture, sitting in an ornate wooden chair on top of carpet. Holding a Buddhist mala, the elderly monk poses, without facial expression, for the camera.

Was he a highly regarded monk – as his portraiture might suggest? A collection of Burmese postcards has recently been digitized by Stanford University, available here: https://exhibits.stanford.edu/missionarypostcards

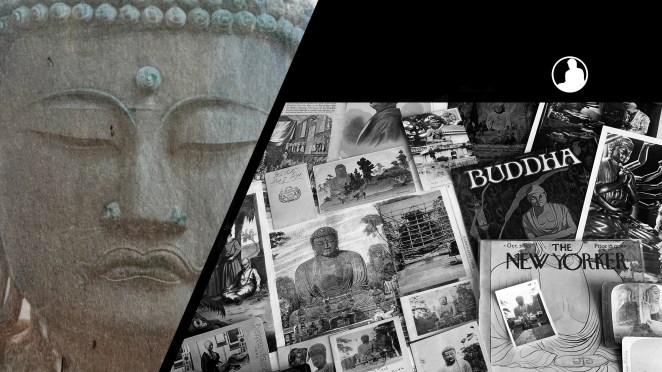

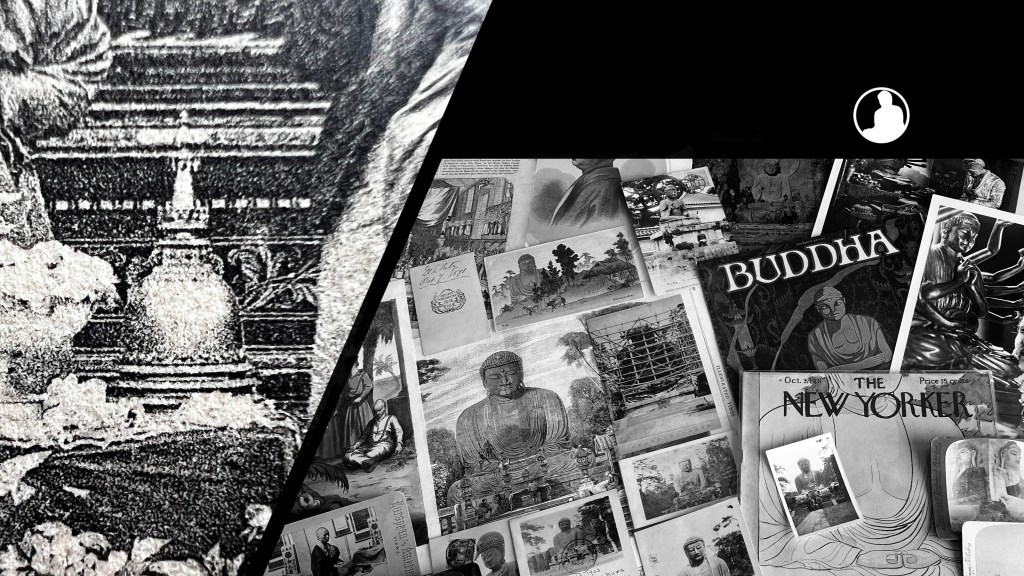

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Buddhist Monastics:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: