Introduction

Is there a value in having university students draw in a humanities course? Admittedly, this is charged question. I do not think practicing still-life drawing would benefit students greatly given the normal range of learning outcomes for a humanities course. But, beyond the perceptual skills being practiced while drawing, is there a cognitive benefit the can be leveraged? From this angle, I absolutely think there is pedagogical value in having students draw.[1]

For those weary of blindly joining me in advancing a “drawing across the curriculum” agenda (a bad joke for my writing colleagues), let me restate what I think drawing can be. For me, drawing is not about mimesis, the creation of a real-world replica on a paper, but about schematization. Drawing is not merely related to sensation, but also cognition and meaning-making. Mental schema function to align a range of perceptual data and convert them into intelligible concepts that can be used. Drawing is simply a physical practice, often overlooked in a non-art classroom, that enables this dynamic intellectual process. (I should note, I am not advocating to incorporate drawing activities to speak to “visual learners” – the myth of different “learning styles” has long since been debunked. Schematizing helps everyone.)

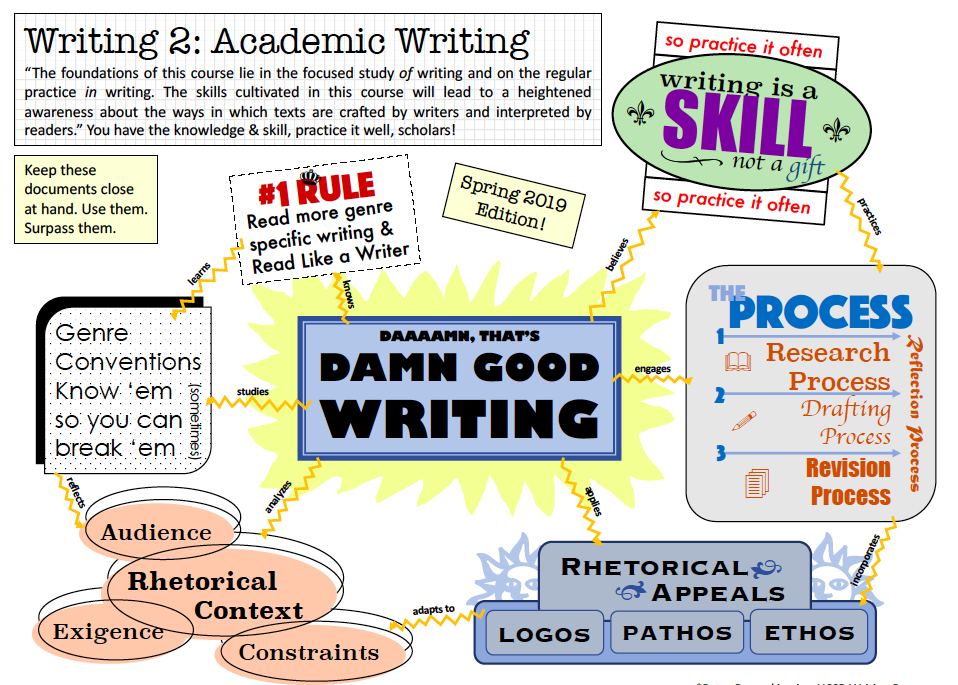

Graphic Organizers (Data Visualization)

One of the most immediate applications of drawing is the creation of graphic organizers, which allow for the construction of knowledge in a hierarchical or relational manner. Organization that is non-linear (unlike linear note-taking or outlining) often leads to better retention and recall. Semantic maps, conceptual maps, Venn diagrams, and tree diagrams (even T-charts) can all be implemented effectively in a classroom environment. If students have difficulty developing them on their own, instructors can assist by making handouts with portions of the charts left blank. I will admit, there is a learning curve to creating more complex graphic organizers, but the goal should be, ultimately, to have your students attempt to create them – doing the conceptual work is where the greatest benefits lay.

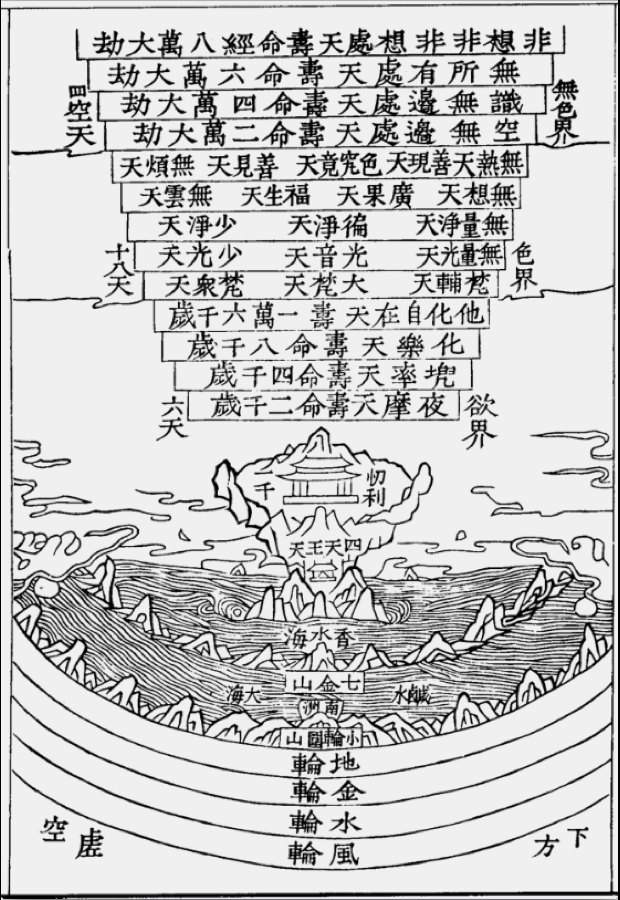

Maps and Other Diagrams

More commonly I have my student draw maps. Instead of showing a map of a region, I will first schematize it on the blackboard – and have my students draw with me.[2] I will then show a proper map after the exercise, mostly to relate what we’ve drawn to what’s on the map. My maps, by choice, are minimalist; I only choose to depict what I think is most pertinent to the content or narrative I am presenting. For example, I often focus on rivers and lakes (the source of life and centers of human activity), or mountains and deserts (obstacles to human movement), or cosmopolitan centers (where documents are often produced, also the civil antipodes to foreign “barbarism”). I can then draw lines to represent human migration or the movement of ideas. This clearly takes more time than simply showing a map on a slide, but I’ve found it to be more effective in crystalizing ideas to students.[3] I’ve also included drawing these minimalist maps (with clear labels) on students exams.

Along these lines, I’ve also spent time drawing mythic cosmologies with my students (e.g. the Buddhist cakravāla and its dhātus – I call it the Buddhist wedding cake), as well as other diagrams produced in the primary materials we are working with (e.g. the bhavacakra). A lot of meaning of often encoded in these endeavors by the original artists and I would argue there is value in (selectively) reproducing them, not only looking at or analyzing them.

Drawing Things

I might hear objections at this point – I am not really having students “draw” things. I believe there is room for this as well, although I would make sure we have a good pedagogical purpose for having students engaging in this (often) time-consuming endeavor. Luckily, for scholars of religious studies (like myself), various forms of artistic production is often at the core of religious practice. Having students participate in traditional religious practices of “art” making (we should always be mindful that some practices will not be considered “art” in the same way as we might approach it) can lead to meaningful interactions with the material under analysis. I can also be, quite frankly, simply fun too.

To provide one clear example, I’ve been having my students draw the important Buddhist figure Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen Buddhism, for several years now. I was inspired when I ran across the contemporary artist, Takashi Murakami, producing modern art versions of this famous Zen monk in 2007. I started scribbling some of my own portraits for fun and eventually decided to try and incorporate this practice into my teaching. At the time I was still looking for excuses to do fun in-class exercises that ask students to take a step out of their normal comfort zones. I was acutely aware that many people feel drawing is an in-born gift, not a skill, and would be hesitant to participate. Ultimately, I like to think that I fool students into drawing, rather than asking them to draw outright.

On the schedule day, I will often bring blank copy paper class and provide two drawing options to my class. I say I will draw Bodhidharma on the blackboard step-by-step and students can choose to follow along, copying my process. Alternatively, students can choose to copy one of several traditional images of Bodhidharma I project on the screen. For those who choose to follow me (typically about half of the class), I imitate my best Bob Ross impression and try to make drawing non-threatening and, hopefully, fun (let’s draw a happy eyebrow right here…).

![drawing Bodhidharma [PC-Peter Romaskiewicz].JPG](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/drawing-bodhidharma-pc-peter-romaskiewicz.jpg?w=581)

The final pay-off for this activity comes at the end. I’ll have students reflect on the types of facial features we’ve drawn on the portrait and guess why they are important to East Asian artists (essentially, Bodhidharma is a caricature of a non-Chinese monk). This is the pedagogical purpose of this activity and I make sure to tie the points we make in discussion to those I’ve made throughout the lecture (if students do not do so already). To further draw out the significance of this activity, and position my students firmly within a actual “Buddhist” artistic tradition, I’ve also created an accompanying reading.

![student Bodhidharma 05 [PC-Peter Romaskiewicz]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/student-bodhidharma-05-pc-peter-romaskiewicz.jpg)

The whole process of handing out paper, introducing the activity, drawing, and discussion takes – minimally – 15 minutes. Of course, you could conceive of projects that take much longer (such as over the whole term) or are completed as teams (based on the suggestion of a colleague, I used to do a textual version of Exquisite Corpse in my composition classes).

Final Thoughts

The real challenge is trying to determine the cost-benefit analysis of drawing – you will be spending far more time with the material than if you just showed the pictures, maps, or diagrams. Thus, as always, be judicious and reflect on the exercise afterwards – was it valuable in helping you to reach a particular learning objective? If at the end of the day, all I do is help my students doodle better, I am completely fine with that.

Notes:

*This is part of an ongoing series where I discuss my evolving thought process on designing university courses in Religious Studies. These posts will remain informal and mostly reflective.

[1] Disclaimer: As the son of an art teacher and professional artist, I’ve always challenged myself to have my students draw more. This notwithstanding, there is some interesting research on art and cognition that I’ve only just begun to dive into. A good primer is Thinking Through Drawing: Practice into Knowledge, edited by Andrea Kantrowitz, Angela Brew and Michelle Fava. Furthermore, there is already copious amounts of literature on incorporating drawing into science classrooms.

[2] This means I also have to tell student to bring paper and pen/pencils to class, quite a sizable portion (in my personal experience) takes notes solely on computers.

[3] There are clearly good reasons to show, and even focus on, highly detailed proper maps, it all depends on your pedagogical purpose. I’d suggest that if you want maps to be more meaningful, drawing elements of them with students can be helpful.

An activity I’ve come to enjoy doing early on in my classes (first day if possible) is to have the students, in small groups, come up with their own succinct, one-sentence definition of religion. Today, when I did this with my Asian Religious Traditions class, I added the instruction that they also had to come up with an apt metaphor for “religion” as well, thus completing the sentence, “Religion is like _______ because it ________.”

An activity I’ve come to enjoy doing early on in my classes (first day if possible) is to have the students, in small groups, come up with their own succinct, one-sentence definition of religion. Today, when I did this with my Asian Religious Traditions class, I added the instruction that they also had to come up with an apt metaphor for “religion” as well, thus completing the sentence, “Religion is like _______ because it ________.”