Introduction

Yesterday, I gave a short university-level workshop on organizing in-class group activities. This was partly a personal conversion story. As an undergrad, I absolutely despised group work. Sure, some of my apprehension was due to my angsty teenage disposition, but – as I’ve come to understand – some was also due to poorly executed planning by my old (but dearly valued) instructors.

My views on group work shifted when I was trained to teach freshman composition and rhetoric at UCSB. Peer-collaboration was highlighted as a student skill that needed to be taught, not just casually performed. Consequently, I returned to my old seminar yesterday to offer insights to this year’s new batch of writing instructors.

The Structuring Group Activities section below is the meat and potatoes of group activity.

Setting the Scene

The class was comprised of about twenty graduate students who all had previous teaching experience. To begin, I asked how many already included group work as an integral part of their classroom practices: Less than one-quarter raised their hands.

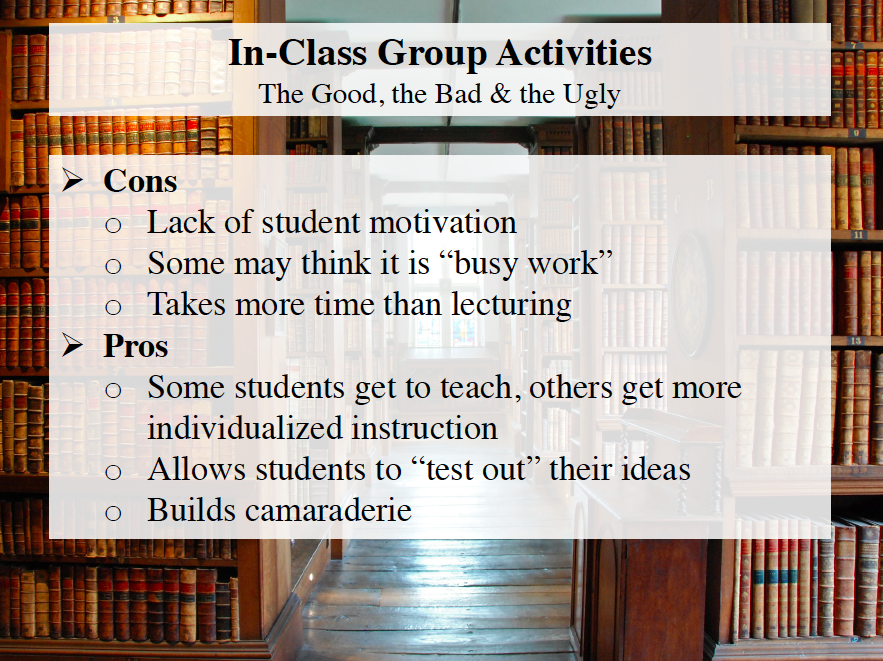

This was not surprising. I’ve found many other had similar negative experiences of group work as students like myself. I then turned to giving an outline of the potential benefits and drawbacks of group work [Slide 1].

Slide 1

Ultimately, I’ve come to feel that the negatives associated with group work can be significantly mitigated (except for the extra time it takes to do it) and the benefits can be amplified if the group activities are structured well.

Structuring Group Activities

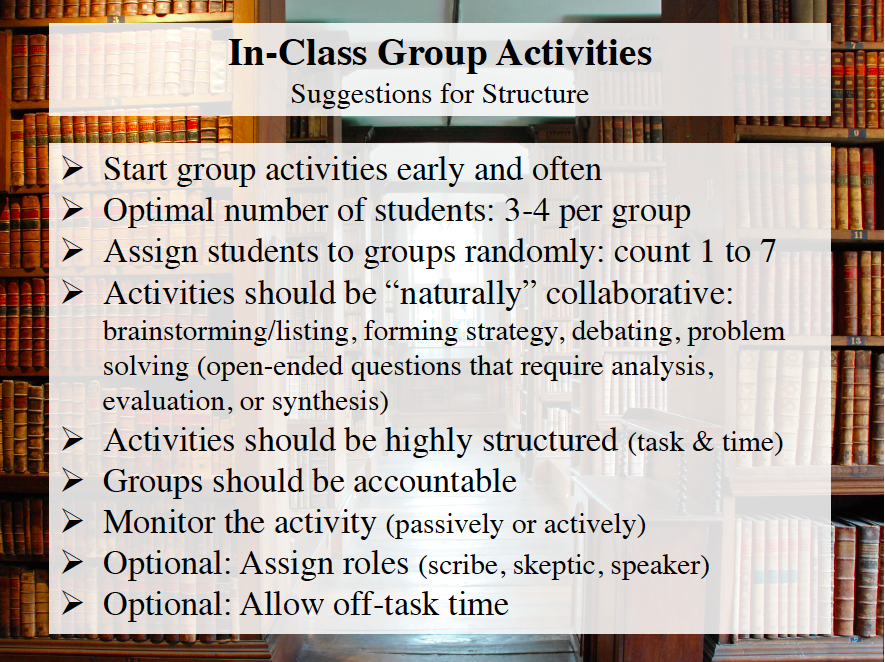

I spent a significant amount of time discussing the elements of an effective group activity [Slide 2]. Each element is described in further detail below.

Slide 2

1. Classroom Culture: Group activities need to be started early and often in the term to establish them as a regular part of class meetings. Group activities should not be treated as a special event nor added to a course halfway through the term when a classroom culture has already been established.

For example, the very first thing I do on the first day of class is break students up into small groups so they get to know each other. I take attendance during this time, so its not wasted time for me. When I’m finished, I ask one student about another student in the group (what’s this person’s name, where are they from?). Often this is followed by a bunch of nervous laughter from everyone in the class as they realize they didn’t pay much attention to one another. I, of course, laugh with them and use this time to comment on the collaborative nature of our course and how important it will be to communicate and listen to one another. (To finish, I let the groups talk to one another again to take notes on names and share emails. I still ask students to introduce other group members, but the conversation remains lighthearted.)

2. Group Size: Groups should always be kept relatively small so no one can “hide” or easily shy away from conversation. I’ve found that three or four members per group is optimal (groups with too many people invite the dreaded “social loafing“). Of course this may not be possible in all classroom settings, but I’ve found that groups of more than five simply do not work.

3. Group Membership: Groups should change from class to class and should not only be comprised of friends or people who sit next to them. I typically have students count off to form random groupings. Because students will need to physically move to a new seat, I always try to do group work early in the class, if not for the first activity.

4. Task & Time: Ideally, group activities should be oriented around open-ended questions that require creativity or discussion/argumentation among the members. If you’re looking for a singular “correct” answer, that’s perhaps not best addressed by a group activity (pair-and-share is suitable). The question(s) the students address should be clear (written on a slide or board) and the time limits should be strict. I always prefer to keep the timing tight, giving students only 3-5 minutes to complete most tasks (the tasks are often not very complex). I use the timer on my phone and allow the alarm to ring to signal the time is up.

For example, I’ll write on a slide: “Create a list of 3 variant hook sentences for this introductory paragraph. You have 3 minutes.”

After 3 minutes, I’ll change the slide: “Determine which of your candidate hooks is the best. Have at least two good reasons why it is the best. You have three minutes.”

Overall, having a clear task and tight time creates an energy and motivation to work quickly and effectively.

5. Accountability: Importantly, groups should always need to produce a “deliverable” – either sharing their ideas verbally with the class, handing in an assignment, or posting on our course website.

6. Monitoring: Sometimes I stay at the front of the room watching or getting other materials ready. Other times I will walk around the class and passively observe/listen to discussion. Sometimes, especially if the group is quiet, I will ask them what they are thinking about or which ideas they are weighing.

7. Roles: To facilitate group interaction and the assumption of personal responsibility, I ask different members of the group to take different roles. One person always operates as a scribe to take “official” notes for the group. (This is important if they are asked to hand in something or post online). Equally, I ask another person to be the speaker. I typically take a friendly, yet partly adversarial role when I talk to the speaker of each group during class collaboration. The speaker will be asked to think on their feet as I ask them to clarify or justify their group’s “deliverable,” or to provide further examples and argue for significance. Sometimes, when the activity allows for it, I also assign the role of the “skeptic.” Their duty is to offer disagreements (ideally, counterarguments) whenever possible, to halt any chance of “group think.” At other times, I will assign the role of “source master” to look up primary quotes or pertinent passages to assist the scribe. In the past, partly for fun, I have also assigned the role of supporter. Their role is to be the hype-person for the group, complimenting the ideas of other members.

To be clear, each group member is tasked with working collaboratively to produce a product for class discussion. Except for the unique role of the speaker, everyone should be taking notes, looking up sources, acting as a skeptic and supporter. The use of “roles” is designed to be an analytical approach to effective group work, identifying smaller inter-group tasks that each student should work on and improve. At least, this reflects my analysis of effective group dynamics, others may certainly have a different analysis.

Lastly, I often let students decide which roles to take, but it reasonable to have roles randomly assigned. For me, I tell students to take roles that reasonably challenge them. If a student is often silent, I’ll recommend taking the role of the skeptic or supporter where they are expected to talk, but with minimal stakes. If the student wants more of a challenge, then try being the speaker of the group.

8. Off-Task Time: Finally, I sometime allow a minute or two of off-task time before or after an activity to let the students get to know each other and build classroom camaraderie. Consequently, even when the task is clearly finished by all groups, if everyone is getting along and chatting, I’d prefer to nourish nascent friendships than have dead silence.

Practice

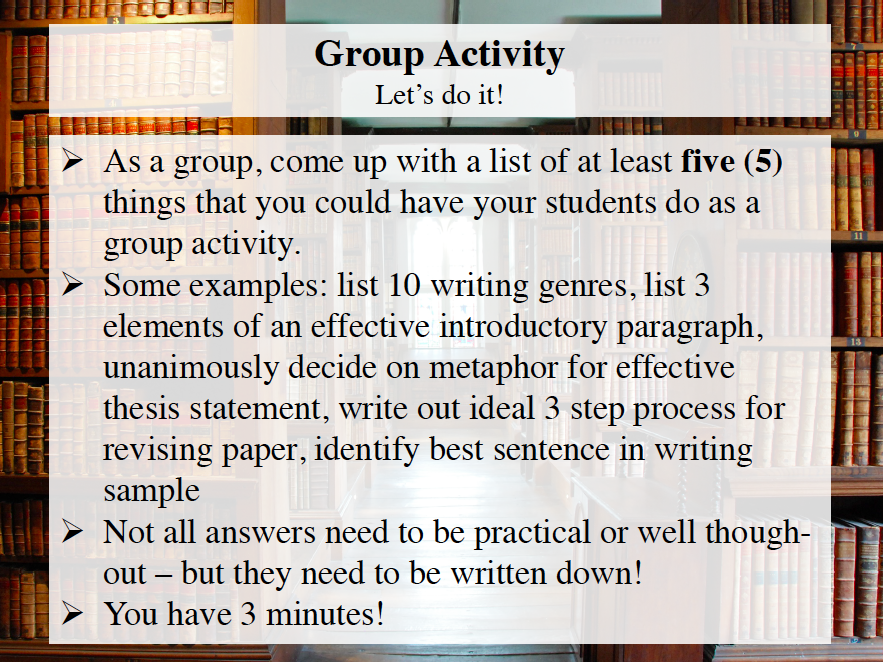

Since this short lecture-workshop was for a class of new writing instructors, I provided them with instructions of how a group activity built for them might look [Slide 3].

Slide 3

Note the question was simple and direct and I provided some examples to stimulate ideas. In addition, there was a clear expectation that the response needed to be written down and there was a clear (short) time limit.

I spent the rest of my class time talking about processes – namely, writing, researching, and reading – which I will return to in a later post.

Workshop Posts

An activity I’ve come to enjoy doing early on in my classes (first day if possible) is to have the students, in small groups, come up with their own succinct, one-sentence definition of religion. Today, when I did this with my Asian Religious Traditions class, I added the instruction that they also had to come up with an apt metaphor for “religion” as well, thus completing the sentence, “Religion is like _______ because it ________.”

An activity I’ve come to enjoy doing early on in my classes (first day if possible) is to have the students, in small groups, come up with their own succinct, one-sentence definition of religion. Today, when I did this with my Asian Religious Traditions class, I added the instruction that they also had to come up with an apt metaphor for “religion” as well, thus completing the sentence, “Religion is like _______ because it ________.”