Introduction

As a trained historian who has (rather belatedly) developed an interest in Instructional Design, I grew curious about its historical origins and development. Quite frankly, The more I learned about various teaching techniques the more I became interested in tracing the trajectories and relationships between specific theories and concepts. This is a cursory attempt to make sense of this field of study and place it in relation to the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, the concept of Active Learning, and the advancements of Educational Technology.

Early Years

The origins of “Instructional Design” (ID) are often traced to the creation of training materials for the military during World War II. Yet, it was not until the 1960’s that a more systematic approach to effective teaching began to appear. This included combining aspects of task analysis, learning objective specification, and criterion testing – all hallmarks of modern higher education – into an overarching model for effective instruction. The elementary principles were derived from the works of psychologists such as B.F. Skinner, Benjamin Bloom, Robert Gagné, and Robert Mager.[1] At this stage, there was interest in creating an overarching “systems approach” to teaching and learning, thus creating what may be now considered a specialized field of study.

As a result of these advances, in the early 1970’s many universities started funding instructional improvement centers (with names such as the “Instructional Systems Development Center”) to help faculty improve the quality of their instruction. In 1977, the first peer-reviewed journal devoted to ID, the Journal of Instructional Development, was published.[2] Moreover, in the same year, the Association for Education Communication and Technology (AECT; originating as the Department of Visual Instruction in 1923) proposed a formal definition of ID centered on five core elements: analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (ADDIE).[3] Thus, ID was founded on a specific methodology focused on improving teaching efficacy.

The interest in teaching instruction faltered in higher education, however, in the 1980s and many of the improvement centers were defunded or disbanded. Furthermore, the Journal of Instructional Development ceased publication in 1988 due to “fiscal austerity.”[4] The 1990s proved to be an important juncture for the study and practice of teaching in higher education.

Constructivism and “Active Learning”

One of the important shifts in the 1990s was the growing interest in constructivism as a learning theory. Constructivism, viewed most broadly, has roots in epistemology, psychology, and sociology, and attempts to explain how people come to know the world around them.[5] Constructionist perspectives on learning are oriented around several principles:

- learning is an active, adaptive process

- knowledge is idiosyncratically constructed through personal filters of experience, beliefs, or goals

- knowledge is socially constructed

- effective learning requires meaningful, authentic (“real world”), open-ended, and challenging problems for the learner to work through[6]

Overall, the constructivist theory of learning is commonly positioned in opposition to the older behaviorist model, where learning is characterized as a passive stimulus-response to highly controlled surroundings. Following this new theoretical approach, learners are no longer treated as inert, empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, but active participants who try to develop effective ways to solve novel problems. While some have criticized this simplistic characterization of behaviorism and the “traditional” views of learning, it cannot be denied that this new interest in constructivism in the 1990s spurred a novel wave of research into optimizing the learning environment for this new conception of the “engaged” learner.[7] Since knowledge (or, anything beyond low-order memorization) cannot be simply be transferred from one mind to another according to this new framework, this leads to an inconvenient reality, namely, “we can teach, even well, without having students learn.”[8] Consequently, developing a full repertoire of teaching strategies based on sound research became ever more important. This coincided with a broader interest in teaching-related scholarship (discussed below).

It should be remembered that constructivism is not an ID theory. Instructional Design attempts to adopt relevant learning theories and develop a systematic approach to effective teaching. It should also be noted that instructional design aims to develop a range of pedagogical techniques – a proverbial pedagogical toolbox – thus, constructivism is only one learning theory that has been adopted. Nevertheless, the 1990s saw a growth in literature speaking to constructivist-based “active learning” environments, so much so that many of the most common teaching best practices today reflect, or have been reinforced by, the so-called constructivist movement.

One of the most well-known targets of active learning proponents is the classical lecture, now sometimes framed (unjustly) as an out-of-date modality of instruction. In 1991, Charles Bonwell and James Eison, authors of the seminal work Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom, proclaimed that “the exclusive use of the lecture in the classroom constrains student learning.” Instead, they promoted instructional activities “involving students in doing things and thinking about what they are doing.” Critics will often interpret this to mean that all lecturing activities need to be replaced by student-led learning initiatives. This is a misunderstanding of the application of active learning. The concern of Bronson and Eison was directed towards the exclusive use of lecturing, where students only take notes and follow directions. To enhance learning, they recommend routinely engaging in activities throughout the lecture where students can reflect upon, analyze, evaluate or synthesize the material that was presented.

These activities can vary greatly, but the general goal is to have students engage in higher-order thinking through reading, writing, and discussing. These can be very simple activities (such as employing think-pair-share) or more complex (such as providing a new reading where a recently learned theory needs to be applied). In practice, these activities are not significantly different from what Michael Scriven called “formative evaluation” (or formative assessment) in 1967. These are assessment procedures performed during the learning process, as opposed to “summative evaluation” (or summative assessment) which takes place at the completion of a learning activity (often measured by exams).[9] A wide range of these activities which provide crucial feedback to students are often placed under the category of Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs), first coined by K. Patricia Cross and Thomas Angelo in 1988.[10]

The point is to puncture lectures with moments of student activity in order to break the line of one-way transmission in exchange for more interactive moments of cognitive processing. This can occur between instructor and student, between students, or function as an individual reflective exercise. While there is no pre-determined time frame to engage active learning activities, the common recommendation is to allow time for reflection and processing every 12-20 minutes of lecture. The timing depends on the complexity, density, and novelty of the information as well as the goals of the instructor. In practice, the instructor revolves between two roles in the active classroom setting, functioning first as the “sage on the stage” by providing important information or modeling procedural knowledge, then acting as a “guide on the side” by coaching and providing feedback to assist in the students’ development.

Teaching Informed by Scholarship

A second shift in the 1990s was the interest in developing scholarly literature that focused on teaching and learning in higher education. The theoretical underpinnings were outlined in Ernst Boyer’s Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professorate in 1990. Boyer was the president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and called for faculty to expand beyond their traditional roles as scholars and consider how to better serve college and university missions to educate an increasingly diverse student population. Boyer proposed re-conceiving scholarship (“the work of the professoriate”) as four distinctive types: scholarship of discovery (e.g. traditional research in one’s discipline), scholarship of integration (e.g. composing introductory textbooks), scholarship of application (e.g. applied research), and scholarship of teaching.[11] It was this last category, scholarship of teaching, where Boyer argued that teaching should not merely be “tacked on” to the duties of faculty, but should be treated as an active area of intellectual exploration where instructors plan, evaluate, and revise their pedagogical approaches based on a rigorous understanding of relevant literature. In other words, teaching and research should not be seen as representing opposing scholarly interests because the research of teaching in higher education is a valuable contribution to scholarship in itself.

Soon after Boyer’s influential publication, other scholars such Robert B. Barr and John Tagg started to highlight the limitations of perceiving higher education as mere access to instruction and suggested examining the value of improving student learning. The suggestions of Barr and Tagg presumed a constructivist theory of education where the focus was centered on the learner.[12] Consequently, the following president of the Carnegie Foundation, Lee Schulman, formally incorporated “learning” into Boyer’s “scholarship of teaching,” thus creating the field of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL, often pronounced “sō-tul”) as it is known today.[13]

While there is no formal criteria for research to fall under the rubric of SoTL, one working definition has been suggested by Michael Potter and Erica Kustra: “the systematic study of teaching and learning, using established or validated criteria of scholarship, to understand how teaching (beliefs, behaviours [sic], attitudes, and values) can maximize learning, and/or develop a more accurate understanding of learning, resulting in products that are publicly shared for critique and use by an appropriate community.”[14] Generally, however, SoTL is rather broad and encompasses any approach to teaching and learning in higher education that mirrors traditional research, namely having defined goals, appropriate methods, significant results, and appropriate presentation.

I have seen no attempts to try and define the relationship between ID and SoTL. Even though they have disparate origins, they tend to share common methods and goals. In practice, because of the specific initiatives of the Carnegie Foundation, SoTL appears to represent the scholarly output of disciplinary specialists interested in researching teaching practices in higher education, while ID represents the pragmatic work done in departments found on campuses (e.g. holding workshops, publishing SoTL-oriented journals [see below], managing informative websites on pedagogy, etc.). These departments often appear under a wide range of names such as the Center for Teaching, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, and Teaching Commons.[15] Perhaps the largest distinction is that historically ID has been interested in all levels of education (including training for business and the military), of which higher education was just one dimension. Additionally, ID has historically shown a closer affiliation with instructional media and technology (see below).

Ultimately, SoTL has become a recognized field of research both within individual disciplines and as a stand-alone discipline. Since 1990, there has been rapid growth in the publication of discipline-neutral journals exploring effective teaching. Below is an incomplete list of running publications falling under the SoTL rubric (including publications that existed previous to Boyer’s publication):

- College Teaching (1953-, formerly Improving College & University Teaching)

- Journal on Excellence in College Teaching (1990-, Center for Teaching Excellence, Miami University)

- Journal of Effective Teaching in Higher Education (1996-, formerly Journal of Effective Teaching, Center for Teaching Excellence and Center Faculty Leadership at the University of North Carolina Wilmington)

- International Journal for Academic Development (1996-, International Consortium for Educational Development)

- Active Learning in Higher Education (2000-)

- Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (2001-, Indiana University’s Faculty Academy on Excellence in Teaching )

- International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning (2007-, Center for Teaching Excellence at Georgia Southern University)

- International Journal of Critical Pedagogy (2008-, UNC Greensboro, The Freire Project)

- International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (International Society for Exploring Teaching and Learning)

- Teaching & Learning Inquiry (2013-, International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning)

- International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research (2014-, Society for Research and Knowledge Management)

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Innovative Pedagogy (2018-, Humboldt State University Center for Teaching and Learning)

- [*A much longer list of journals related to higher education can be found here*]

Numerous disciplines also have a history of studying how students learn within their fields, such as history (Teaching History, 1969-), sociology (Teaching Sociology, 1973-), or philosophy (Teaching Philosophy, 1975-), among many others. While SoTL research tends to be less tied to specific disciplinary domains, some will include these publications under the SoTL rubric. A helpful list of journal publications devoted to teaching and sorted by discipline is published digitally by the University of Saskatchewan Library (here).

Educational Technology and Instructional Media

A third shift in the 1990’s, which I will only discuss briefly here, was the growing interest in using computers and eventually the internet, for instructional purposes. Historically, we could trace the origins of ID to pre-World War II interests in technological advancements perceived as having an application for teaching. This would include early twentieth-century school museums and new visual media such as magic lantern slides and stereoview cards. In the coming decades, this interest would shift to the use of video and television.[16] This focus on researching (and adopting) the newest technology for the classroom is revealed in the name of one of the oldest professional groups dedicated to ID, the Association for Education Communication and Technology (AECT), which was started in 1923 as the Department of Visual Instruction. Additionally, many of the earliest journals dedicated to ID, published under the editorial supervision of the AECT, had titles such as A[udio] V[isual] Communication Review, Tech Trends, Media Management, and School Learning Resources. After World War II, Educational Technology (also known as Instructional Media, among other names) was increasingly seen as separate from the research interests of the newly developing field of ID. While these fields clearly overlap, they also covered specific, complementary niches.[17]

Some of the more recent interests of this field are the development and management of university Learning Management Systems (LMS) and the designing of online or blended classrooms, especially for long-distance courses. This has spawned a new major in several American colleges and universities called Learning Design and Technology (LDT).

TL;DR

Many Instructional Development departments in colleges and universities operate useful, information-rich websites. If I had to choose just one on the merits of providing ample, practical information about university pedagogy while also providing some historical context, it would be the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching (if you navigate to the Center for Teaching home page, look for the Teaching Guides menu).

Notes

[1] I am indebted to Reiser 2001a and Reiser 2001b for this synoptic history of Instructional Design.

[2] The use and study of various forms of instructional media, such as audio-visual materials, is often treated as a parallel area of study to instructional design, with the recent focus on the use of computers and long-distance education.

[3] For discussion on the various definitions of Instructional Design see Branch & Dousay 2015: 14-8, and Reiser 2001a: 53-4. Robert Reiser offers a more nuanced definition of Instructional Design: “The field of instructional design and technology encompasses the analysis of learning and performance problems, and the design, development, implementation, evaluation and management of instructional and noninstructional processes and resources intended to improve learning and performance in a variety of settings, particularly educational institutions and the workplace. Professionals in the field of instructional design and technology often use systematic instructional design procedures and employ a variety of instructional media to accomplish their goals. Moreover, in recent years, they have paid increasing attention to noninstructional solutions to some performance problems. Research and theory related to each of the aforementioned areas is also an important part of the field.” See Reiser 2001a and 2001b. Some have suggested that instructional development mirrors the scientific method, see Andrews & Goodson 1980.

[4] Higgins et. al. 1989: 8. Technically, the Journal of Instructional Development was combined with Educational Communication and Technology Journal (titled previous to 1978 as A[udio] V[isual] Communication Review) and consolidated as Educational Technology Research and Development. Additionally, the publications Tech Trends, Media Management, and School Learning Resources were also consolidated, see Higgins et. al. 1989, also see Dick & Dick 1989: 87.

[5] The figures most prominently associated with constructivism are Lev Vygotsky and Jean Piaget. See, e.g. Owen-Smith 2018: 17-8.

[6] There is no consensus definition of the constructivist theory of learning, but a survey of the literature suggests a polythetic dimension. For delineations of the elements of constructivism see, among others, Fox 2001: 24, Reiser 2001b: 63, and Karagiorgi & Symeou 2005: 18.

[7] For a summary overview of critiques against the novelty of constructivism, see Fox 2001. I agree with Fox that it is highly unlikely any “traditionalist” view of learning proposed the learning process to be entirely passive. For a list of scholarship exploring the relationship between constructivism and more “traditional approaches, see Reiser 2001b: 63. Furthermore, in the camp of constructivism, there are more radical and more conservative views regarding the relative importance the external environment and internal, individual frameworks; see the brief discussion in Karagiorgi & Symeou 2005: 19.

[8] Karagiorgi & Symeou 2005: 18.

[9] The precursors to Scriven’s helpful distinction between formative and summative is discussed in Cambre 1981.

[10] Their recommendations were published in Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for Faculty. A collection of videos explaining some of these techniques can be found at the K. Patricia Cross website.

[11] This is outlined in Chin 2018: 304.

[12] Barr and Tagg differentiate between the Instruction Paradigm and the Learning Paradigm, see Barr & Tagg 1995.

[13] This is also reflected in the Carnegie Academy for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (CASTL) launched in 1998. For Shulman’s analysis of the importance of learning, see Shulman 1999. A brief history of SoTL can be found here (by Mary Huber) and here (by Nancy Chick).

[14] Potter & Kustra 2011: 2.

[15] It seems plausible to say that SoTL has superseded ID as the preferred terminology to name this field of research.

[16] See Reiser 2001a.

[17] See, e.g. Dick & Dick 1989.

References:

- Andrews, Dee H. & Goodson, Ludwika A. 1980. “A Comparative Analysis of Models of Instructional Design.” Journal of Instructional Development, pp. 161-82.

- Barr, Robert B. & Tagg, John. 1995. “From Teaching to Learning: A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education,” Change, Vol. 27, No. 6, pp. 13-25.

- Bonwell, Charles & Eison, James. 1991. Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports.

- Boyer, Ernst. 1990. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: Princeton University Press.

- Branch, Robert Maribe & Dousay, Tonia A. 2015. Survey of Instructional Design Models. Bloomington: Association for Educational Communication and Technology.

- Cambre, Marjorie A. 1981. “Historical Overview of Formative Evaluation of Instructional Media Products,” Educational Communication and Technology, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 3-25.

- Chin, Jeffrey. 2018. “Defining and Implementing the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning,” in Learning from Each Other: Refining the Practice of Teaching in Higher Education, eds. Michele Lee Kozimor-King, Jeffrey Chin, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 304-11.

- Cross, K. Patricia & Angelo, Thomas. 1988 [1993]. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for Faculty, 2nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Dick, Walter & Dick, W. David. 1989. “Analytical and Empirical Comparisons of the Journal of Instructional Development and Educational Communication and Technology Journal.” Educational Technology Research and Development, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 81-87.

- Fox, Richard. 2001. “Constructivism Examined,” Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 23-35.

- Higgins, Norman; Sullivan, Howard; Harper-Marinick, Maria & López, Cecilia. 1989. “Perspectives on Educational Technology Research and Development,” Educational Technology Research and Development, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 7-18.

- Karagiorgi, Yiasemina & Symeou, Loizos.2005. “Translating Constructivism into Instructional Design: Potential and Limitations,” Journal of Educational Technology & Society , Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 17-27.

- Owen-Smith, Patricia. 2018. The Contemplative Mind in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Potter, Michael K. & Kustra, Erika D.H. 2011. “The Relationship between Scholarly Teaching and SoTL: Models, Distinctions, and Clarifications,” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol. 5, No. 1, Art. 23.

- Reiser, Robert A. 2001a. “A History of Instructional Design and Technology: Part I: A History of Instructional Media,” Educational Technology Research and Development, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 53-64.

- Reiser, Robert A. 2001b. “A History of Instructional Design and Technology: Part II: A History of Instructional Media,” Educational Technology Research and Development, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 57-67.

- Shulman, Lee. 1999. “Taking Learning Seriously,” Change, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 11-17.

![In Defense of Lectures? [Part II]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/lecture-ii-banner-romaskiewicz.jpg?w=662)

![In Defense of Lectures? [Part I]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/lecture-i-banner-romaskiewicz.jpg?w=662)

![How Does One Do “Religious Studies”? Religious Studies Paradigms [Part III]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/rs-banner-romaskiewicz.jpg?w=662)

![How Does One Do “Religious Studies”? Religious Studies and Humanities [Part II]](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/rs-banner-romaskiewicz-1.jpg?w=662)

I’m continually amazed how the efforts of random bloggers make my life as a writing instructor all the more easier.

I’m continually amazed how the efforts of random bloggers make my life as a writing instructor all the more easier.

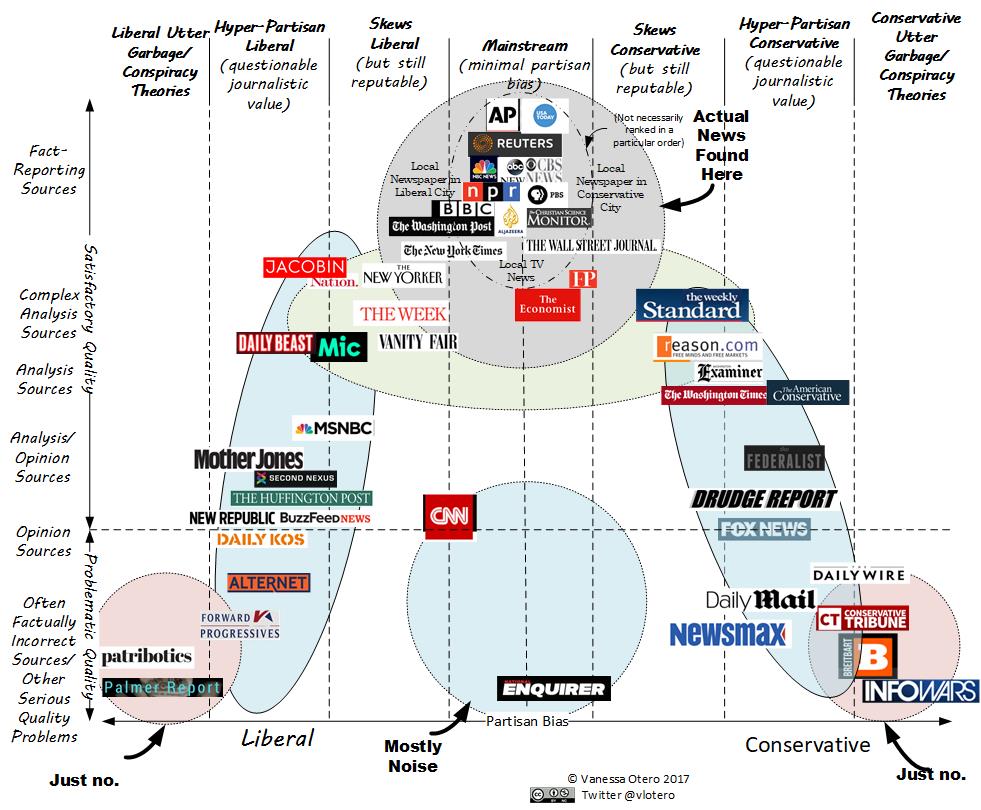

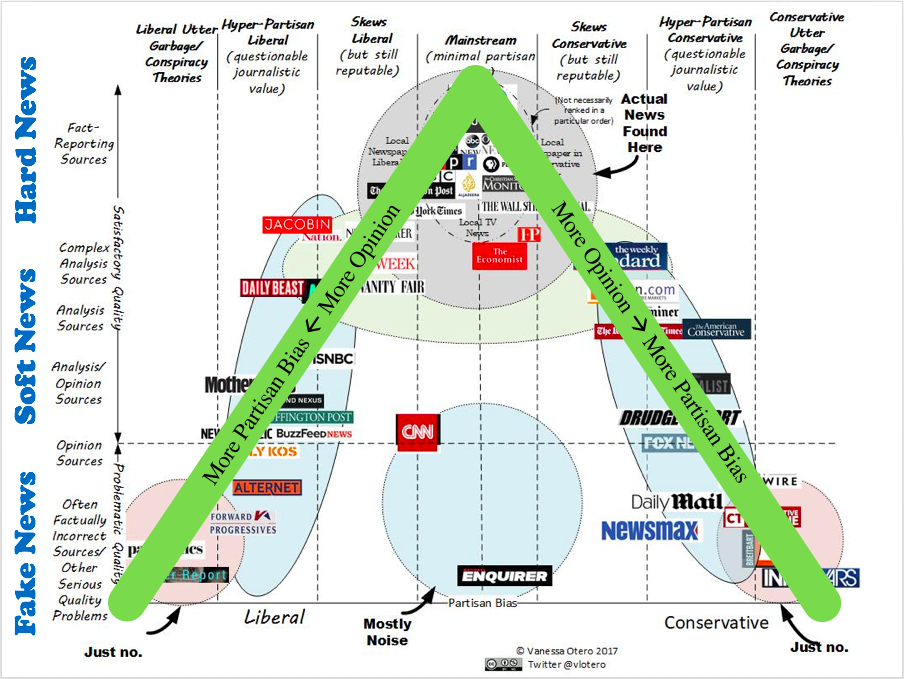

This lead me down a train of thought which wanted to play with audience and several other types of cognitive biases. In other words, how do certain cognitive biases direct what and how we read? I was reminded of the fabulous chart, originally posted by blogger

This lead me down a train of thought which wanted to play with audience and several other types of cognitive biases. In other words, how do certain cognitive biases direct what and how we read? I was reminded of the fabulous chart, originally posted by blogger