For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

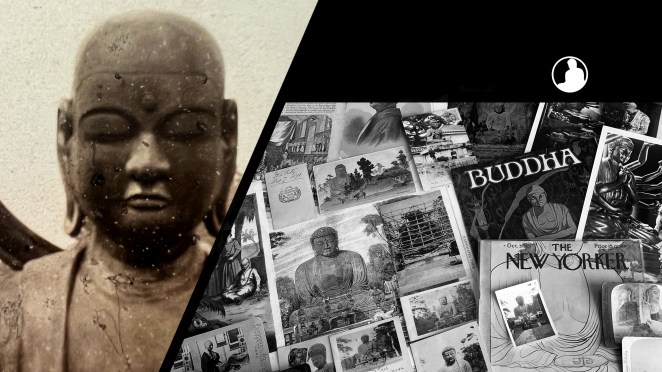

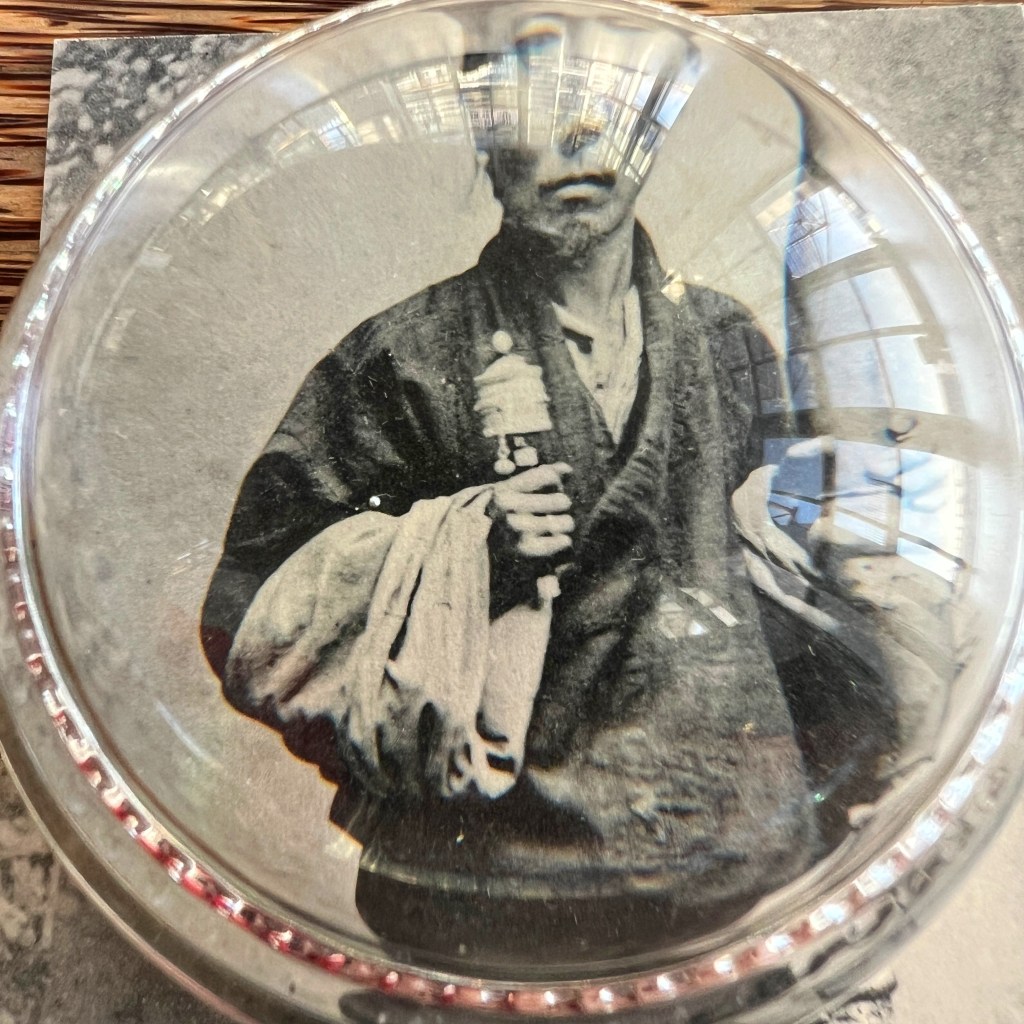

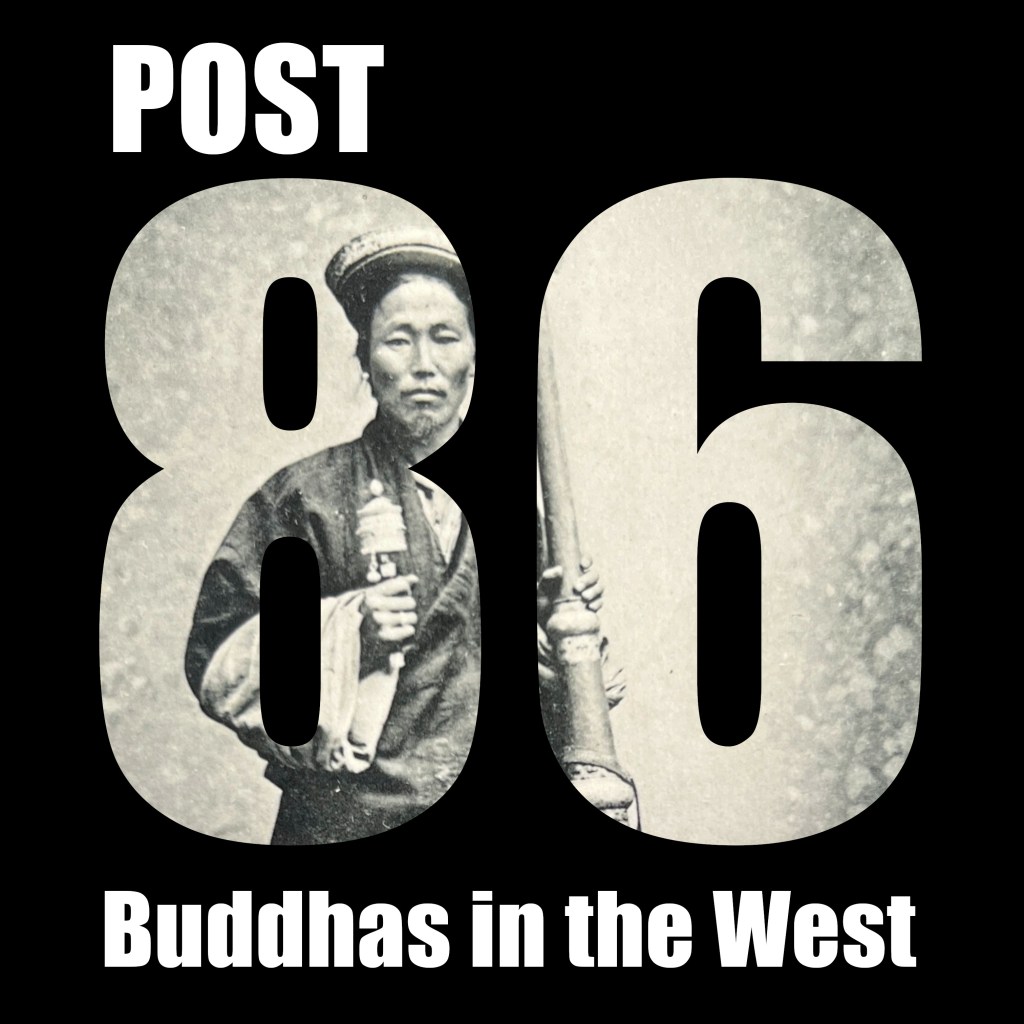

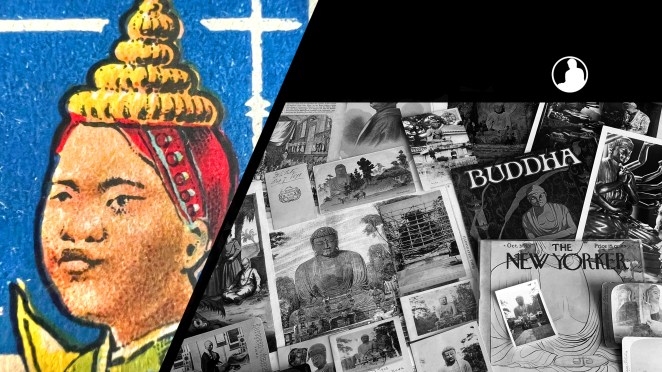

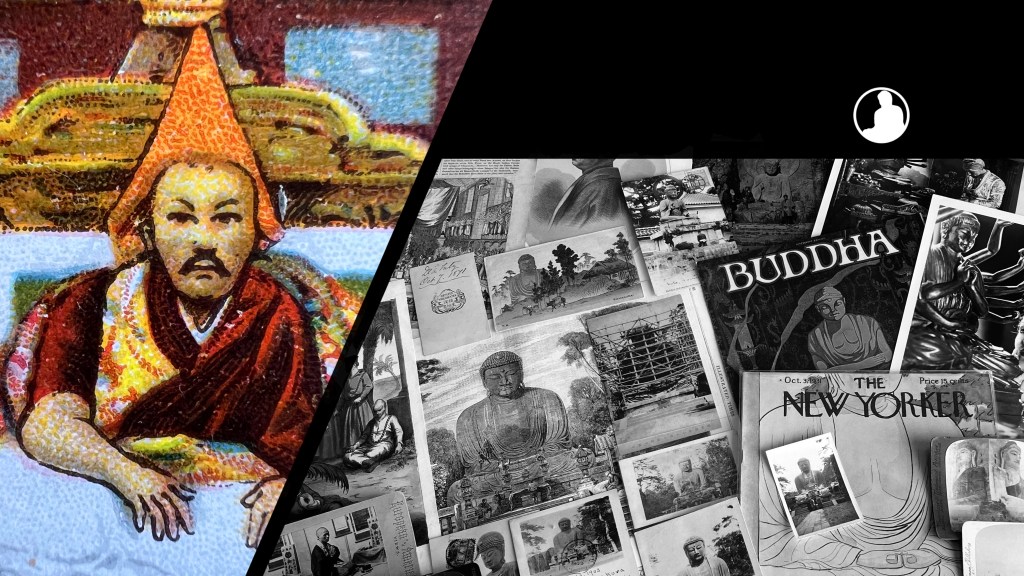

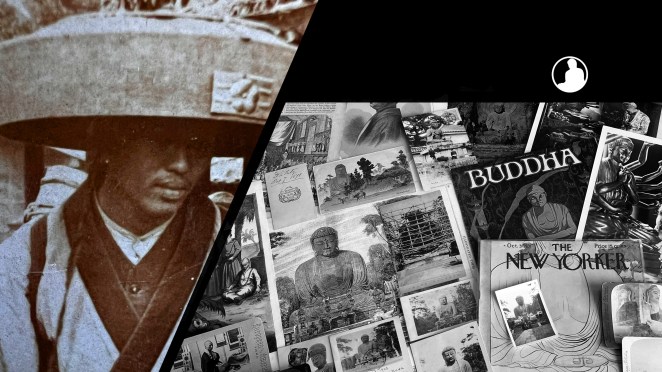

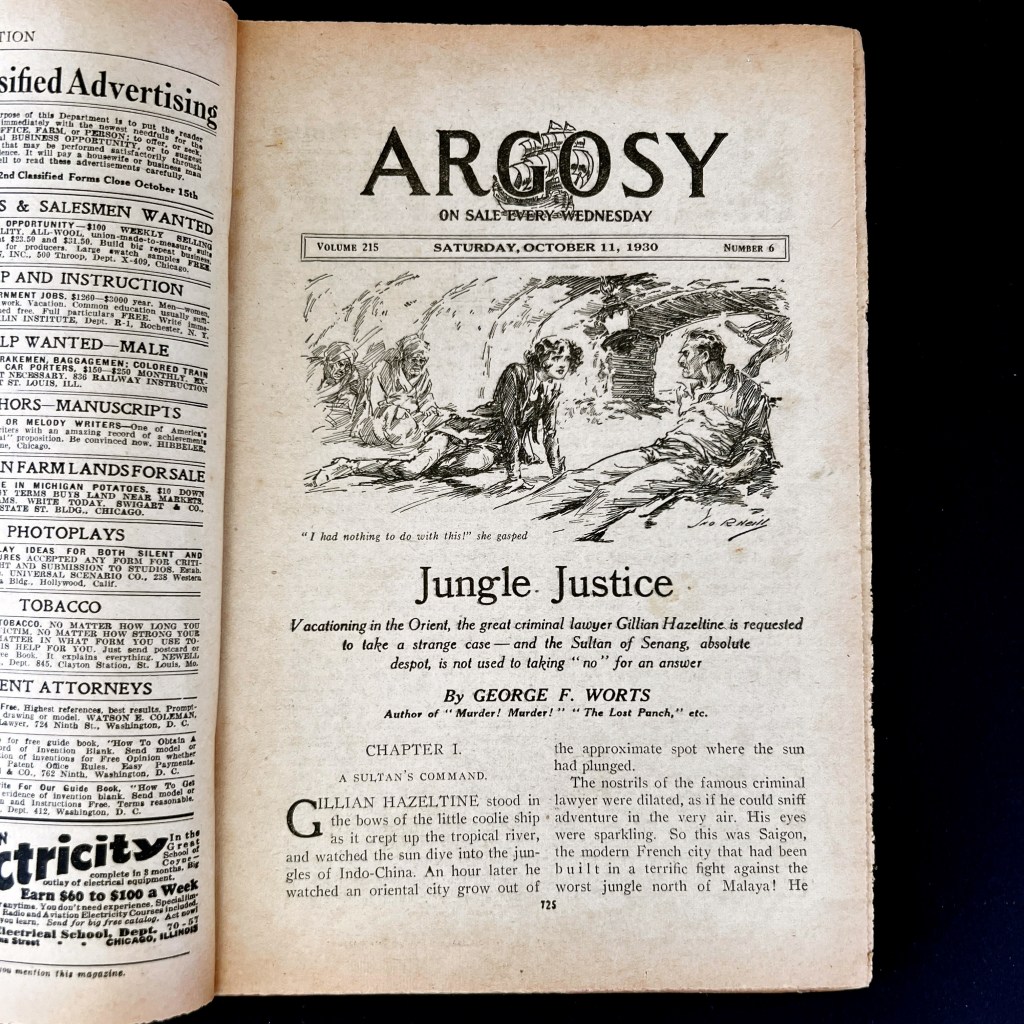

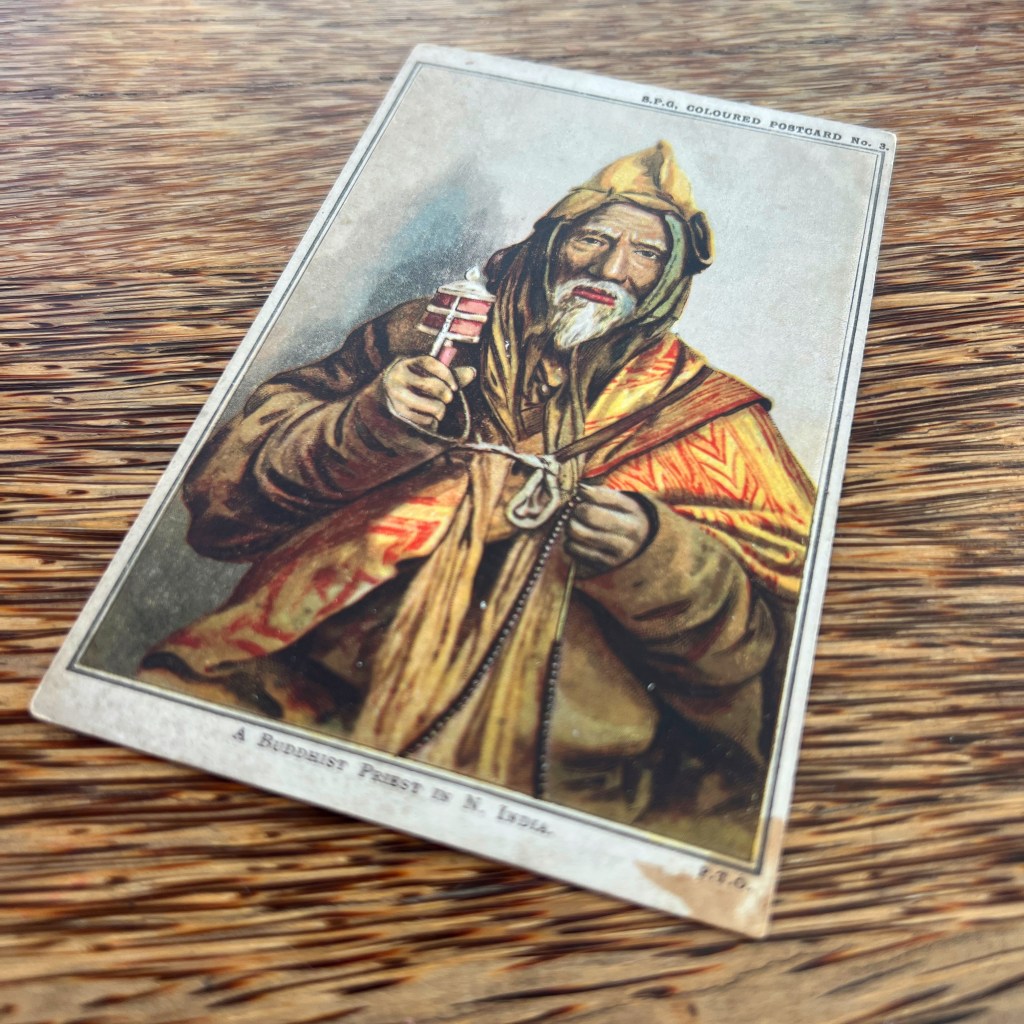

Identified as a “Buddhist priest” and holding a prayer wheel, a figure such as this would have passed for a generic Tibetan lama in the visual language of the early 20th century. In this case, however, we also know this monk’s name: Sherab Gyatso.

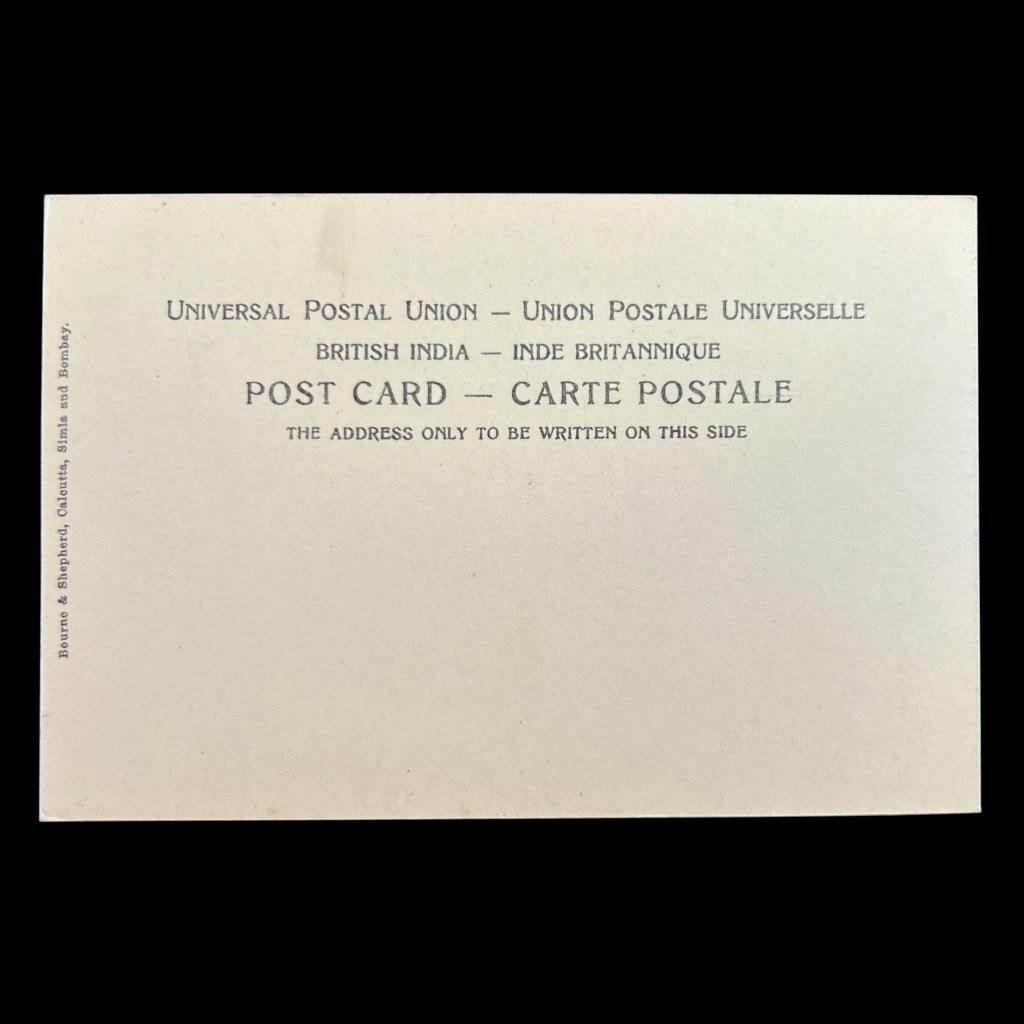

Scholar Clare Harris discovered an albumen print of the original photograph taken by Thomas Parr during the 1890s in Darjeeling; the negative was inscribed with the name “She-reb.” The monk was the head of the Geluk Monastery at Ghoom (Ghum) and was well known among the British as the “Mongol Lama.”

Gyatso’s image appears in a wide range of media, including travel guides, published travelogues, and postcards between 1890 and the 1910s. As noted by Harris, this monk emerged as a “poster-boy for Tibetan Buddhism” around the area of Darjeeling in northern India.

When posed for this portrait in Parr’s studio, the symbols of Tibetan ritual culture are clearly foregrounded, with one hand thumbing mala beads and the other holding a prayer wheel upright and ready for use.

Notably, a Tibetan-style painting and clay statue of Sherab Gyatso grace Ghoom’s monastery today, both derived from Paar’s photograph.

For further information of Sherab Gyatso and the history of early photography in Northern India and Tibet, see Clare Harris’ Photography in Tibet (2017).

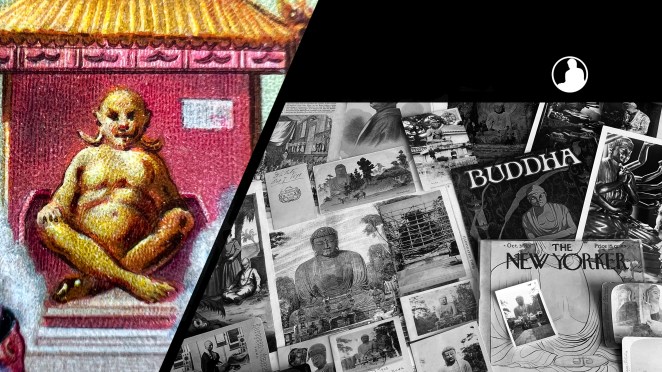

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Historical Postcards:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: