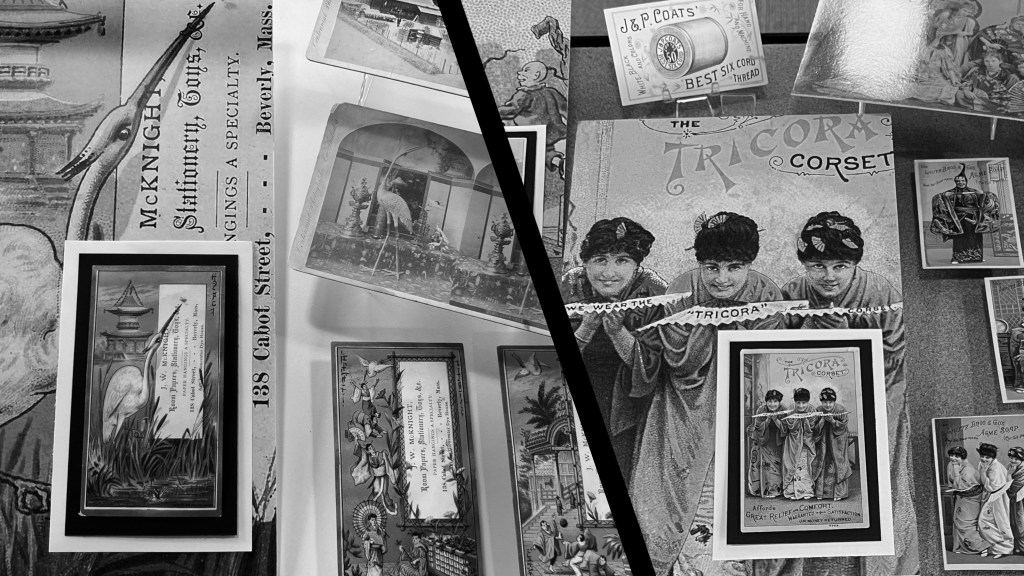

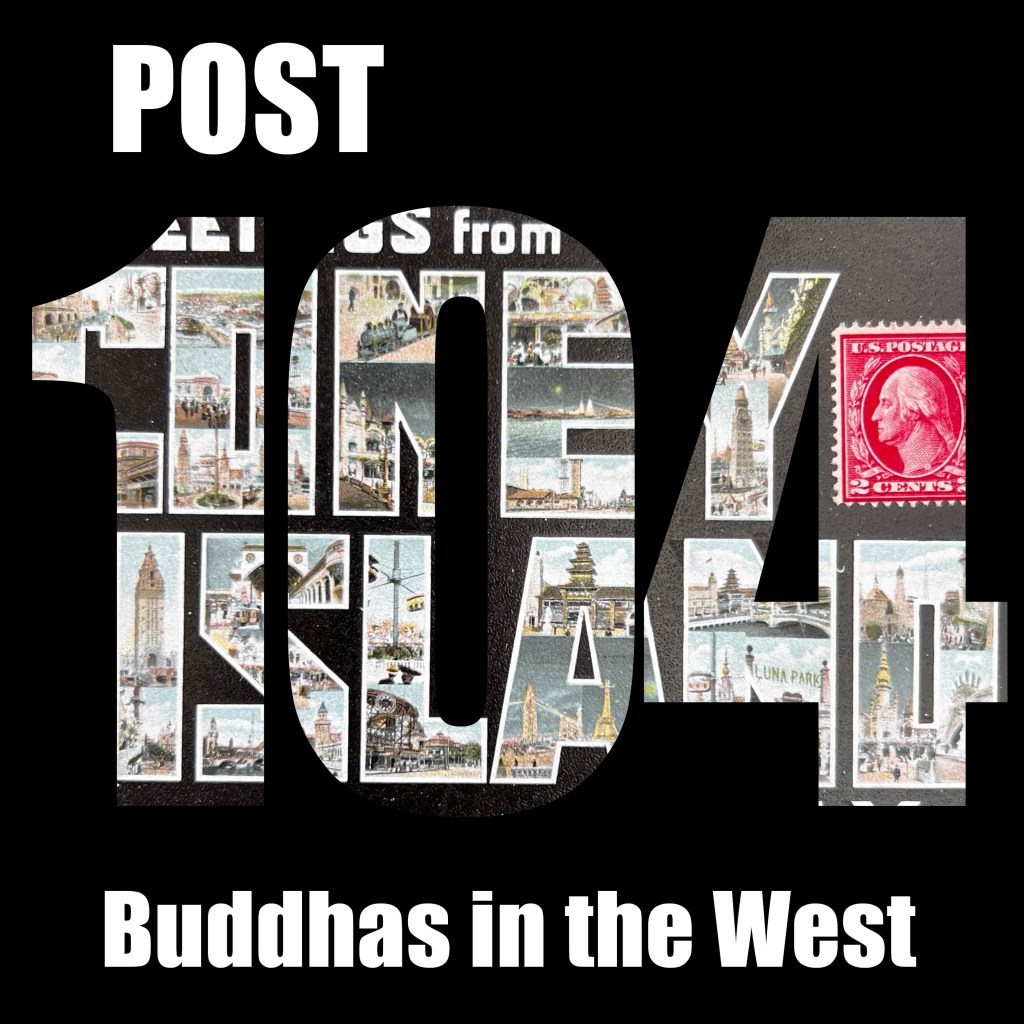

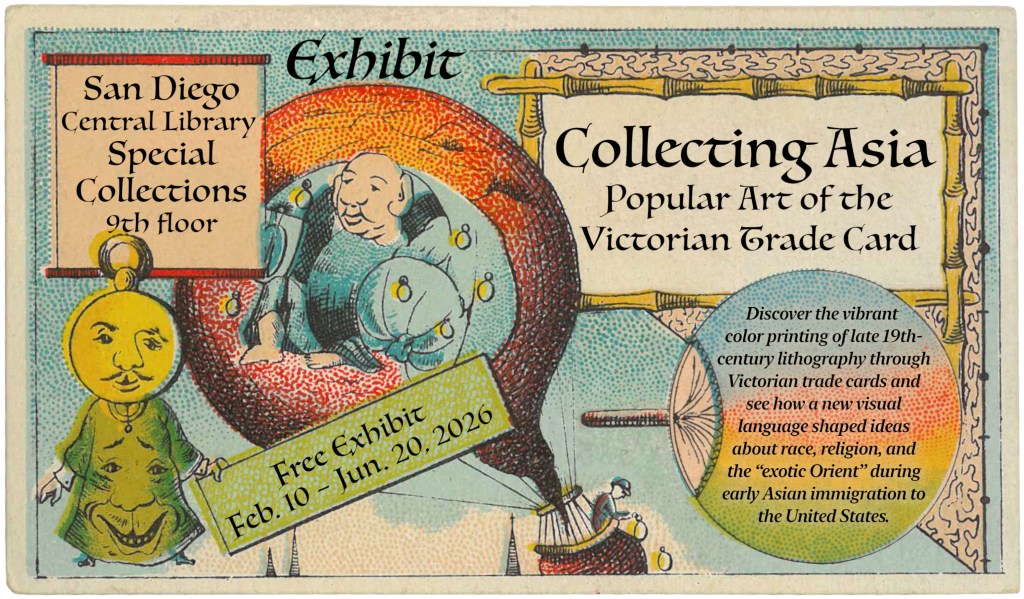

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive exhibit, “Collecting Asia: Popular Art of the Victorian Trade Card,” is featured at the San Diego Central Library, Special Collections, from February 10 through June 20, 2026.

Welcome to the Companion Guide

This accompanying digital companion guide offers a high-resolution Deep Zoom Image Gallery and an informative De-Coding Guide for six key trade cards on display—one for each of the six main visual themes: Performing Asia, The Japan Craze, Chinese Exclusion, The Mikado Craze, Buddhist Vogue, and Globetrotting Asia.

The exhibition explores the “color revolution” of late nineteenth-century lithographic printing through early advertising trade cards. The exhibit focuses on depictions of Asia and Asian American life across fifty trade cards to see how a visual language around race, religion, and the “exotic Orient” was created during the first major wave of Asian immigration to the United States.

In the late nineteenth century, as black-and-white engravings dominated the pages of books, magazines, and newspapers, a “color revolution” in lithography began to reshape the American imagination. Vibrant broadsides, richly printed package labels, and colorful trade cards emerged as mass-produced canvasses to express commercial and cultural ideas.

This technological shift coincided with a transformative era in American society: the first major wave of Asian immigration. Beginning with Chinese workers in the mines, forests, and railroads of the West, and followed by Japanese, Korean, and Filipino immigrants, these new arrivals fundamentally altered the nation’s demographic landscape.

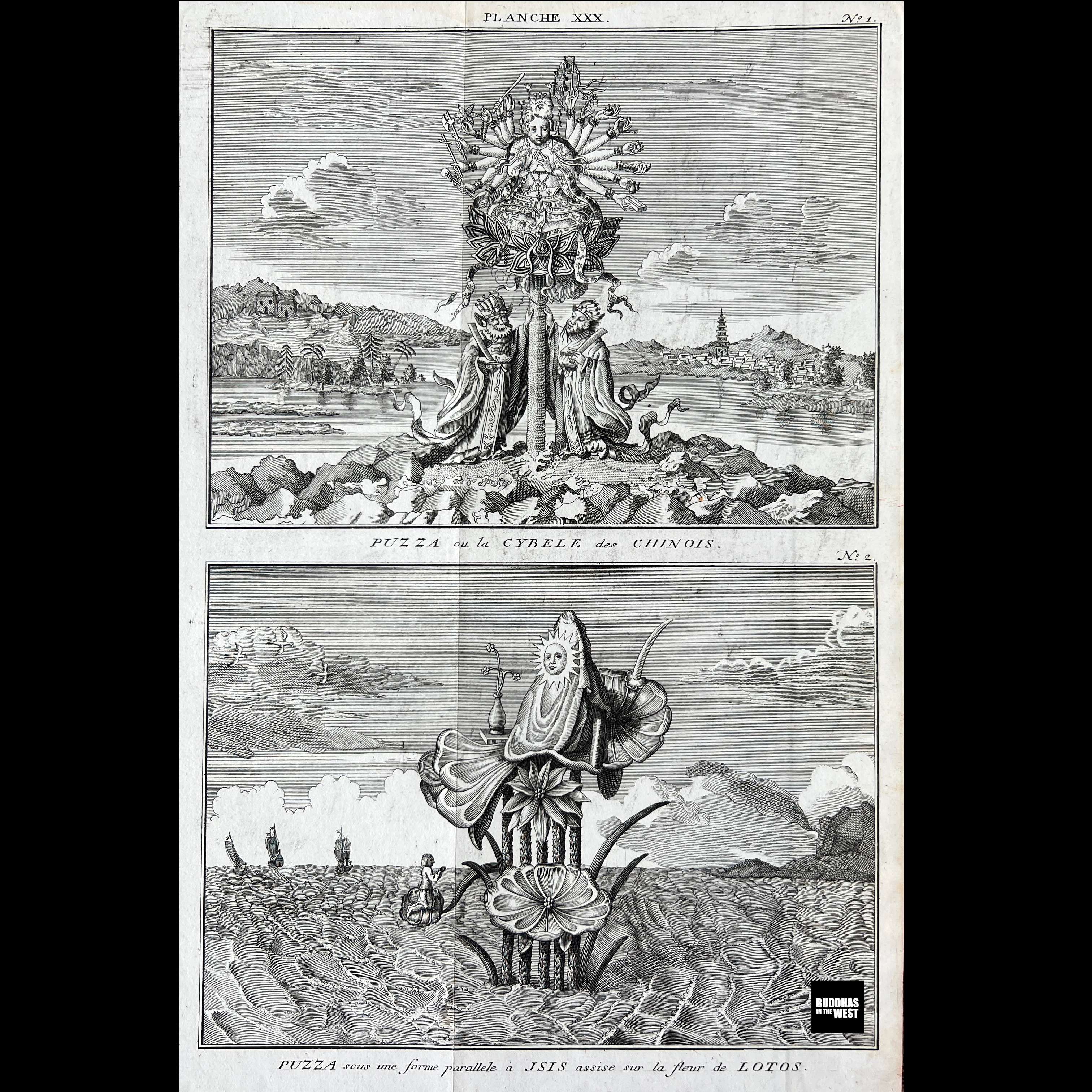

This exhibit explores the confluence of new print technology and shifting racial and religious demographics. Asia has long occupied an ambiguous space in European and American imaginations, simultaneously perceived as a land of alluring exoticism and a source of threat.

These tensions come into focus through trade cards, the vibrant advertising ephemera of the Victorian era. These cards were inserted into product packaging or distributed over the counter at dry goods stores. Prized for their visual appeal, trade cards also became popular collectibles among Victorian scrapbookers, many of them children, who were inevitably shaped by the highly stereotyped imagery the cards so often conveyed.

To collect these trade cards was to curate a fantasy of Asian identity—one that often replaced the reality of Asian and Asian American lives.

To Consider:

- How have advances in print and digital technology helped or hindered our understanding of a multi-cultural America?

- How has our visual language for “the Other” changed in 130 years?

Deep Zoom Image Gallery & De-Coding Guide

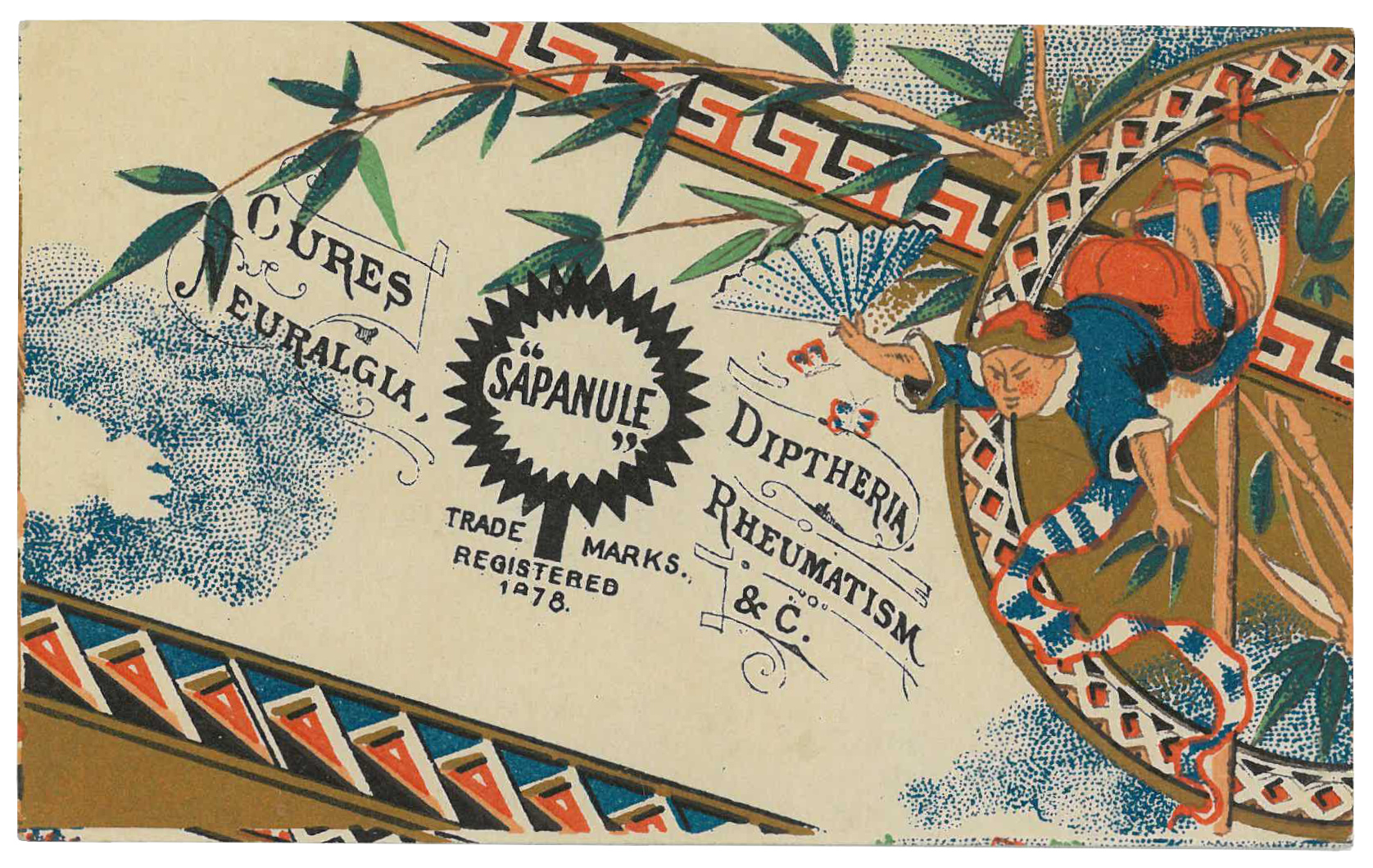

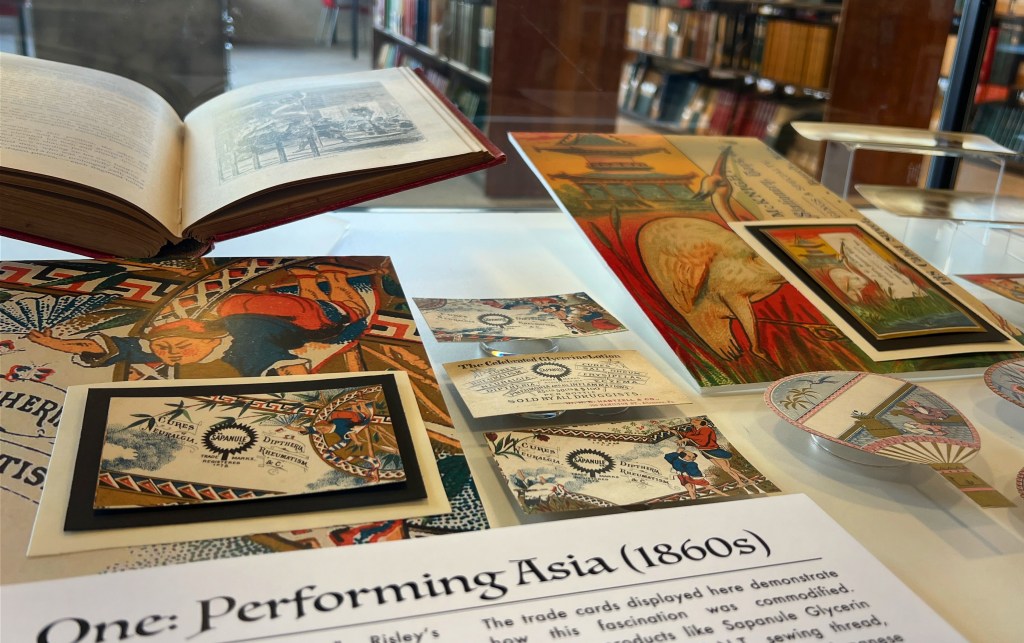

Key Card 1: Performing Asia (1860s)

Sapanule exemplifies late nineteenth-century patent medicines that dramatically overstated their effectiveness. Although glycerin—the only listed ingredient—is an effective moisturizing agent for certain skin conditions, the claims to treat diphtheria and rheumatism are unfounded.

As was typical of the time, the imagery on trade cards had little direct relationship to the products being marketed. Sapanule issued a five-card series featuring scenes associated with Japan, printed by lithographer L. Sunderland in Providence, Rhode Island.

The images were not original, however. The were elements copied from a series of engravings first appearing in Swiss diplomat Aimé Humbert’s writings on Japan published in the late 1860’s. Several of those illustrations focused on Japanese street performers, acrobats, and jugglers and were copied by many subsequent publications on Japan, including Edward Greey’s 1882 book, Americans in Japan, also seen in the exhibit.

To Consider:

- Two Sapanule trade cards on display replicate elements of the illustration seen in Greey’s Americans in Japan. Can you identify them?

- How does the repetition of imagery across different media reinforce specific kinds of stereotypes?

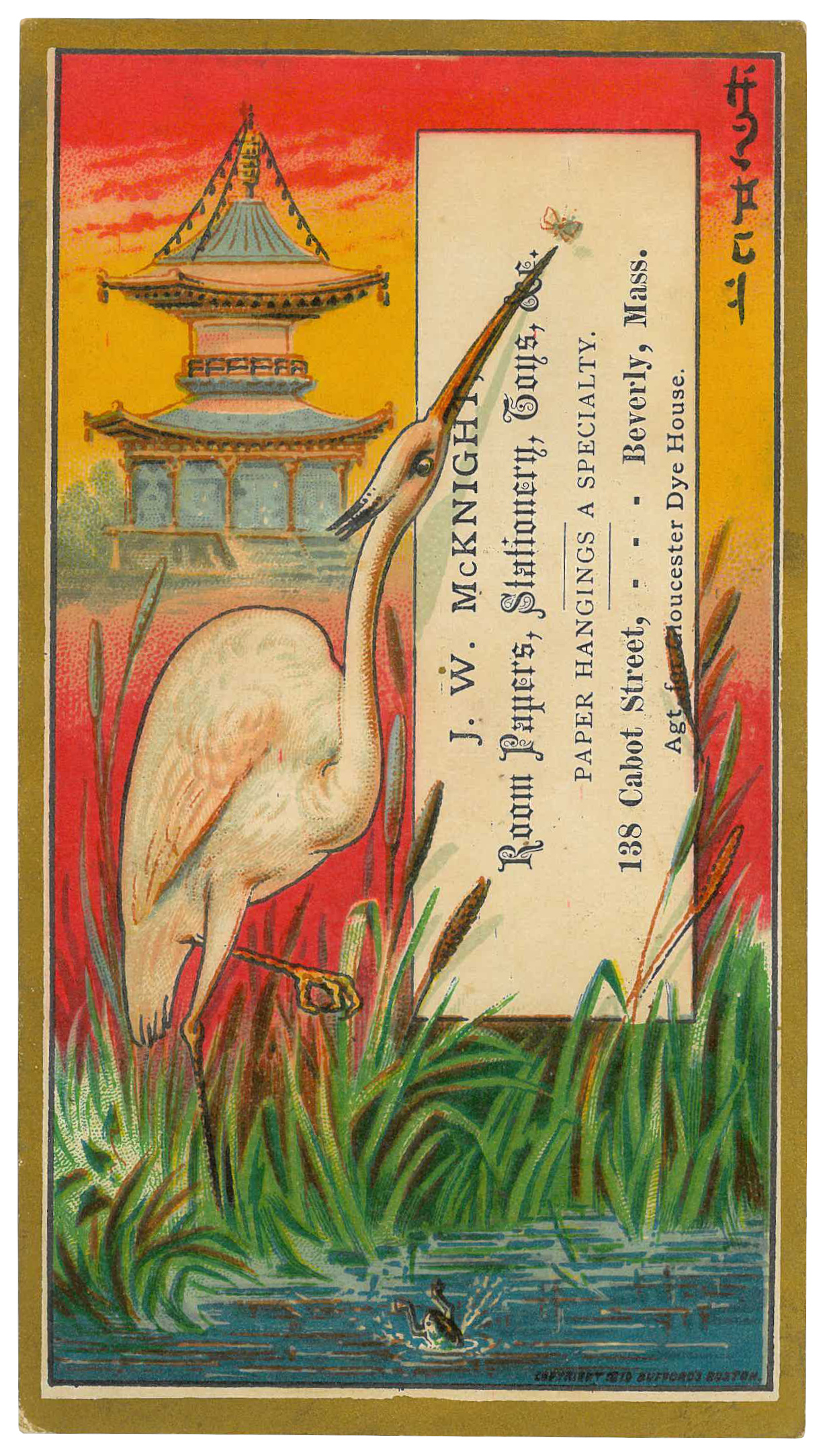

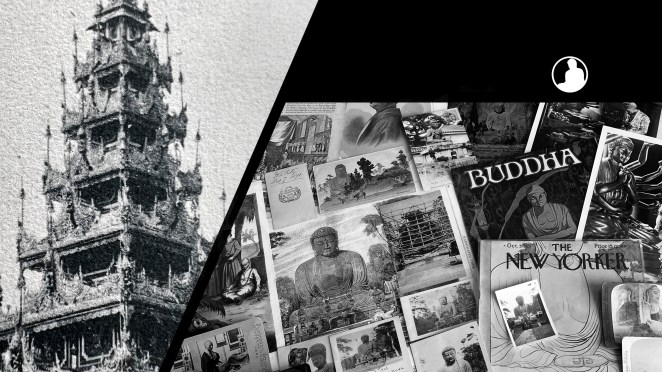

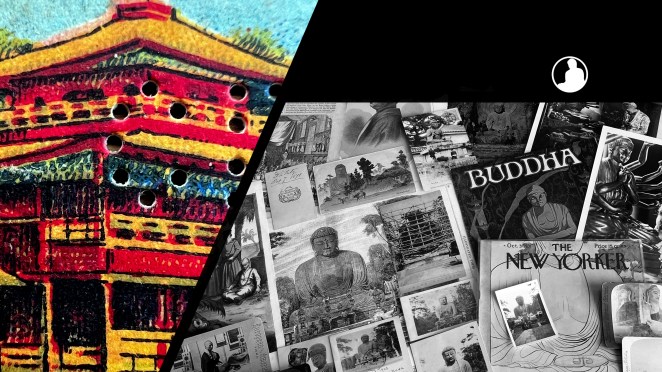

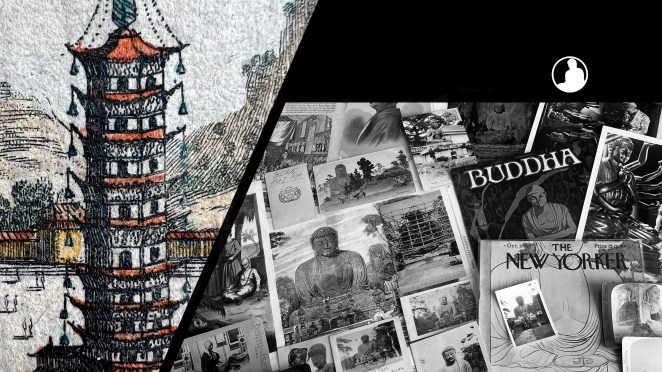

Key Card 2: Japan Craze (1870s)

The Boston-based printer John H. Bufford & Sons was among many lithographers who produced stock trade cards designed to be overprinted with the names and addresses of local businesses. In one three-card series issued by Bufford, Japan appears as a tranquil fantasy landscape framed by a gold-ink border that visually “packages” the country as a luxury object.

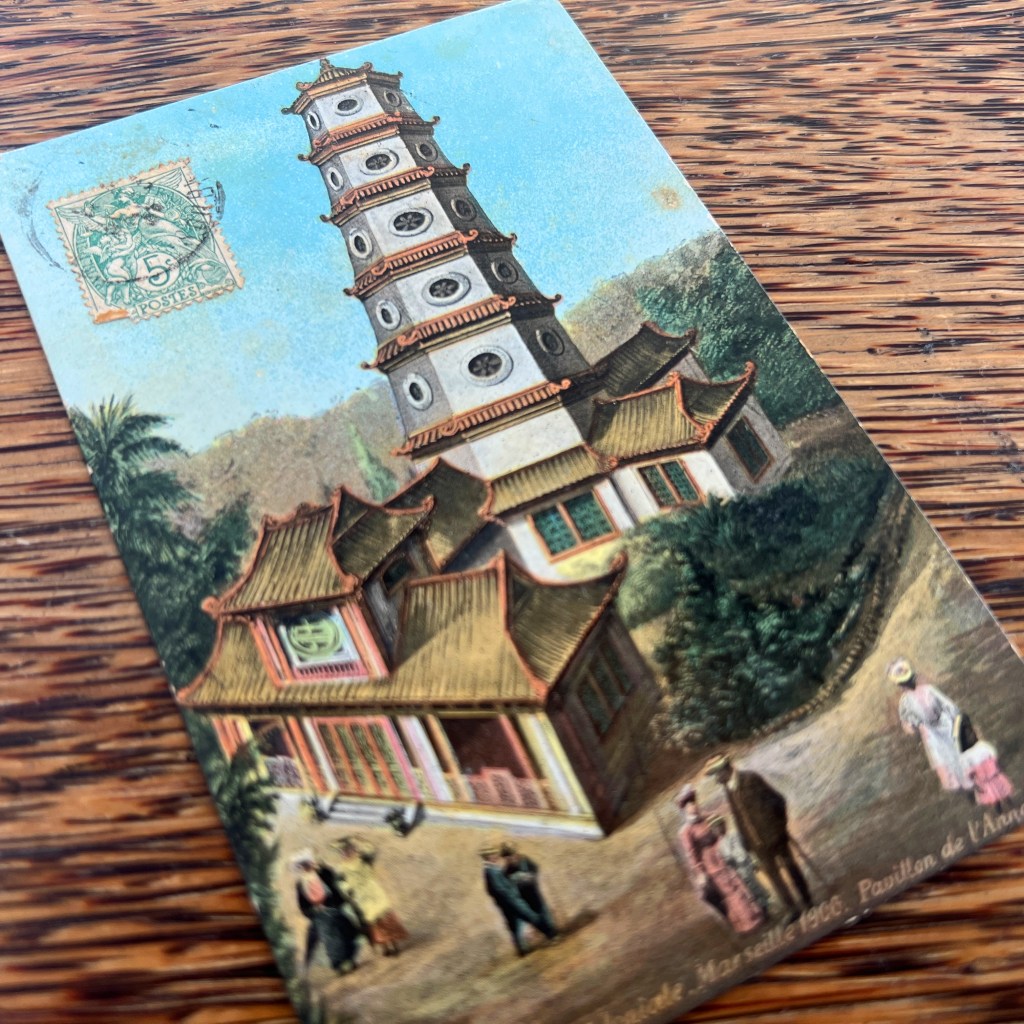

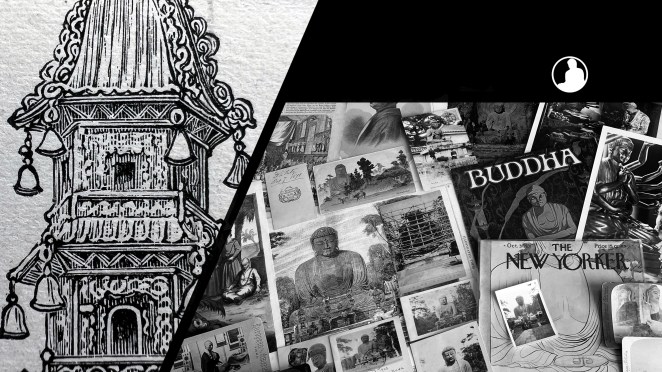

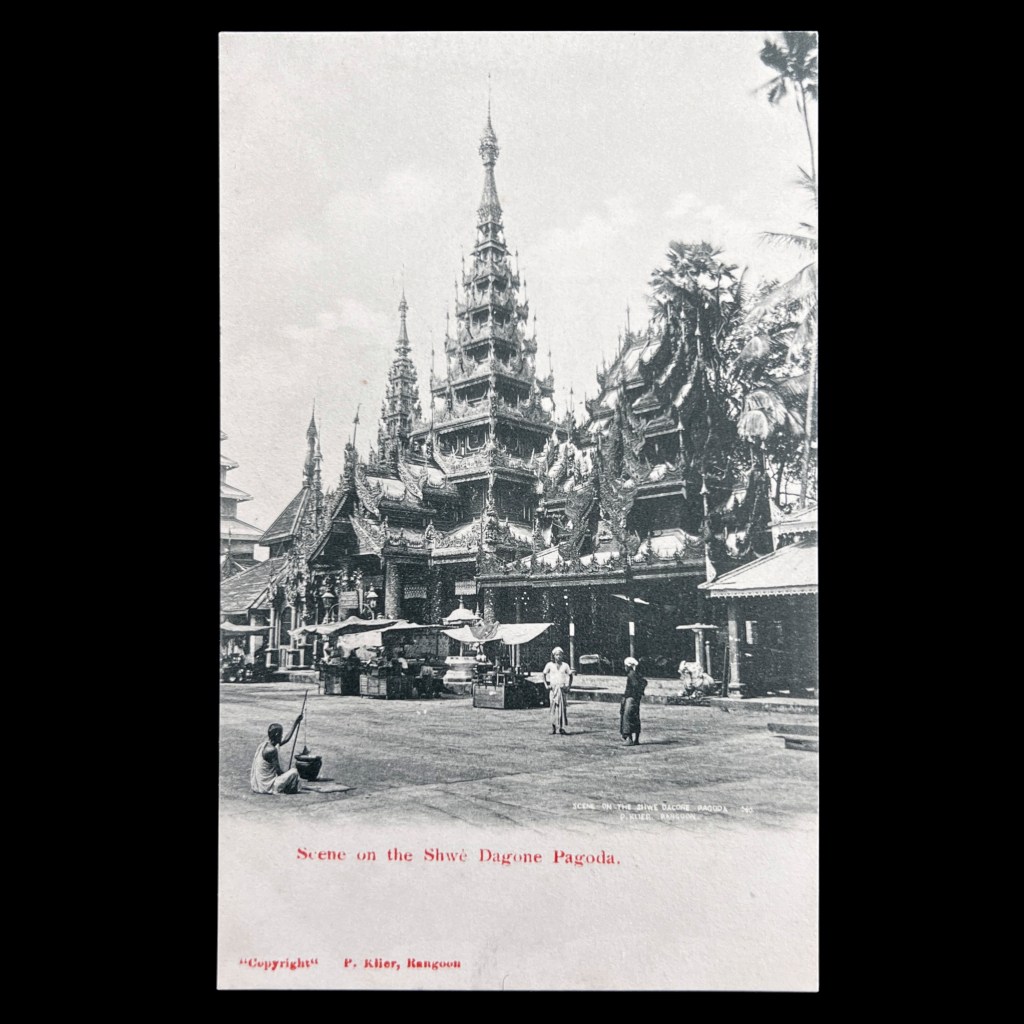

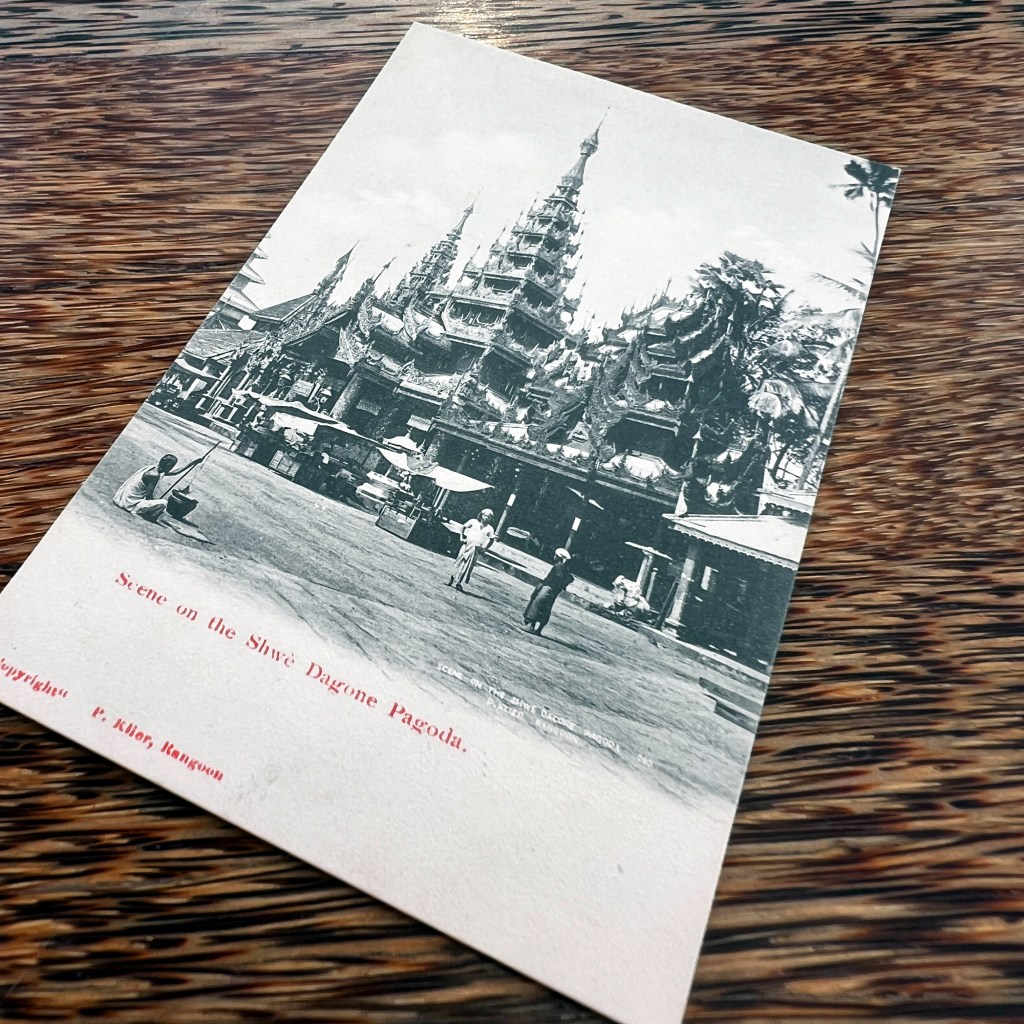

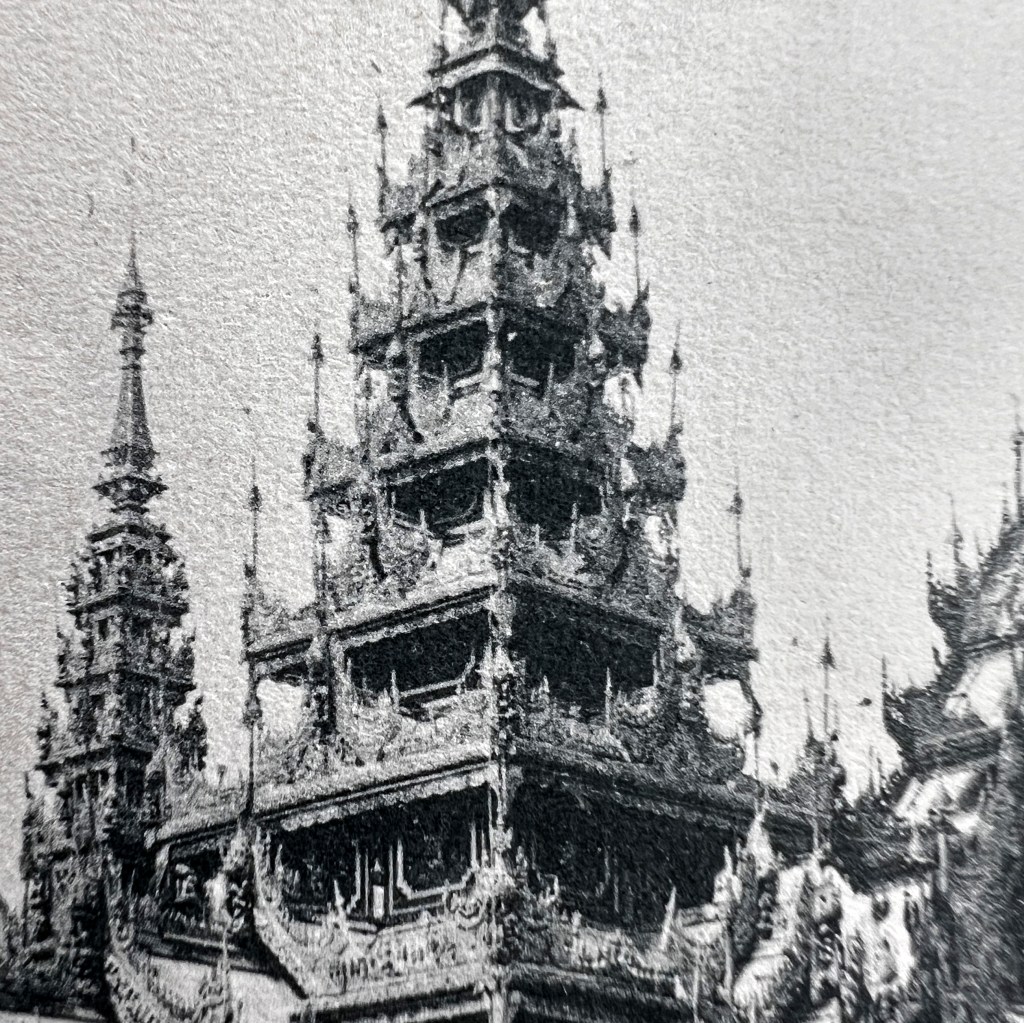

A Buddhist pagoda, seen in the top left, was a centuries-old visual icon for depicting East Asian landscapes. The pagoda here was copied from Aimé Humbert’s writings on Japan in the 1860s and depicts a building at Hachiman’s Shrine in Kamakura, Japan.

Likewise, the elegant Japanese egret was also emerging as a symbol of Japan in Western media. During the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Japanese representatives built a Japanese “bazaar” and displayed delicately wrought bronze sculptures, including egrets, as seen in the stereoviews accompanying this display.

Imagery of pagodas and egrets became common decorative motifs in American Japonisme, encompassing a period sometimes called the “Japan Craze,” which reflected a growing interest in a Japanese aesthetic influencing fine art, architecture, and domestic decor. This helped cast Japan as a land of refined curiosities and provoked mass consumption of everyday objects, laying the groundwork for early modern consumerism.

To Consider:

- What challenges to cross-cultural understanding arise when a culture is encountered primarily through its commercial products?

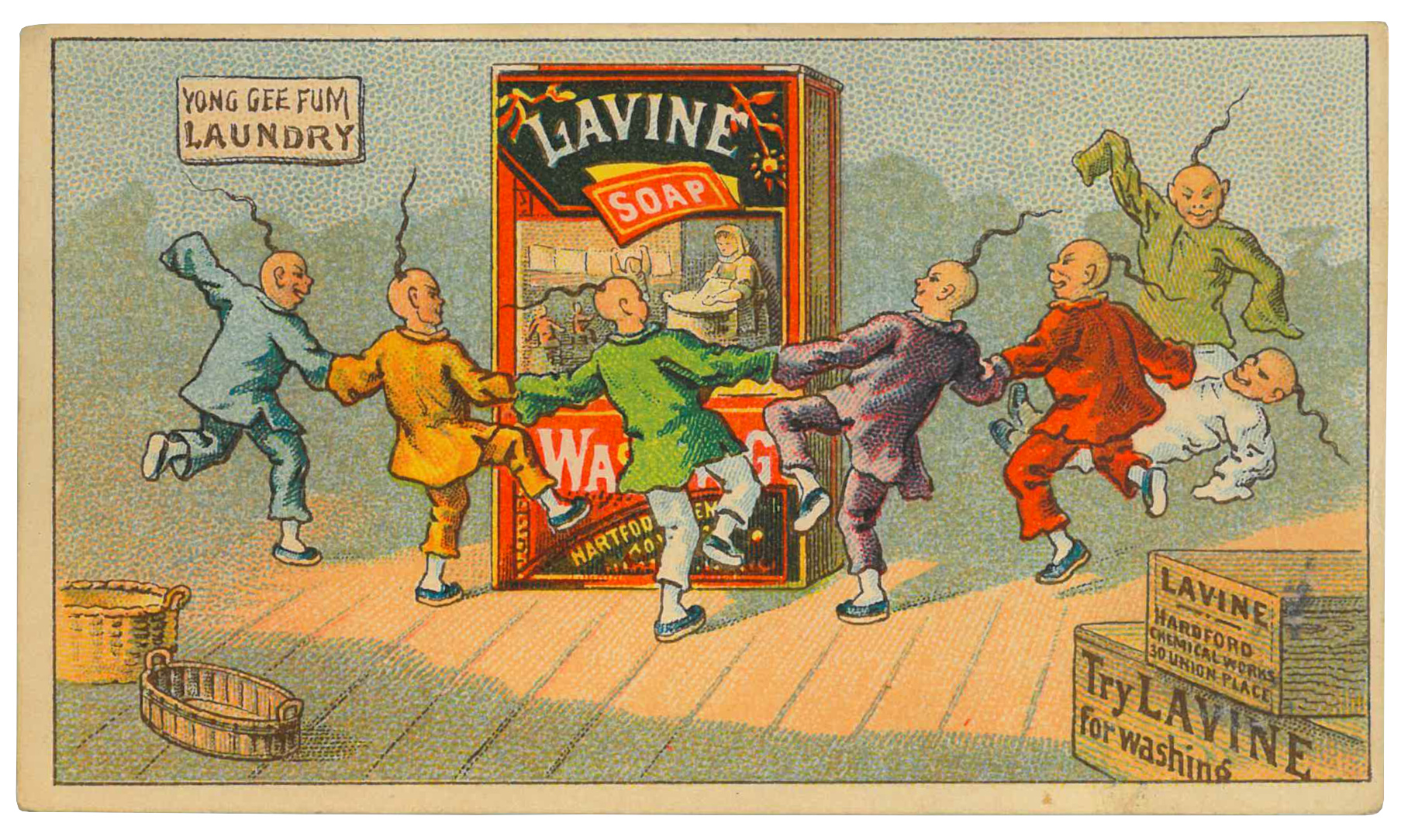

Key Card 3: Chinese Exclusion (1882)

Trade cards often promoted products for use in the home, such as sewing machines, stove polish, and quick-rising flour. Washing and laundry soap were also promoted as remedies for the burdens of household labor. This Lavine Soap card depicts Chinese men dancing around an oversized soap box in exaggerated delight—an image that appears playful, but reveals deeper racial and economic tensions.

During the first major wave of Asian immigration, Chinese laborers faced widespread discrimination that pushed many into self-employment, including operating groceries, restaurants, and laundries. Although trade card imagery often lacked direct connection to the advertised product, the association between laundry soap and Chinese laundrymen would have been immediately recognizable to an American audience. While seemingly light-hearted, this card speaks to the limited employment and economic opportunities for Chinese immigrants.

Moreover, by the 1870s, political leaders and labor organizers blamed Chinese “coolie labor” for declining wages, culminating in federal legislation that barred Chinese immigration in 1882. Other trade card advertisements suggested new consumer goods could replace Chinese labor entirely, echoing the anti-Chinese slogan “The Chinese must go.” This is clearly apparent in the trade cards promoting waterproof shirt collars and cuffs trade as seen on display. It is believed the originator of the “Chinese must go” slogan, Denis Kearney, is depicted on the Celluloid collars and cuffs card as the mustached man in profile swimming in the ocean.

To Consider:

- What accounts for the reason why Asian countries were generally viewed as favorable “exotic” lands, but Asian immigrants were viewed unfavorably as threats?

Key Card 4: Mikado Craze (1885)

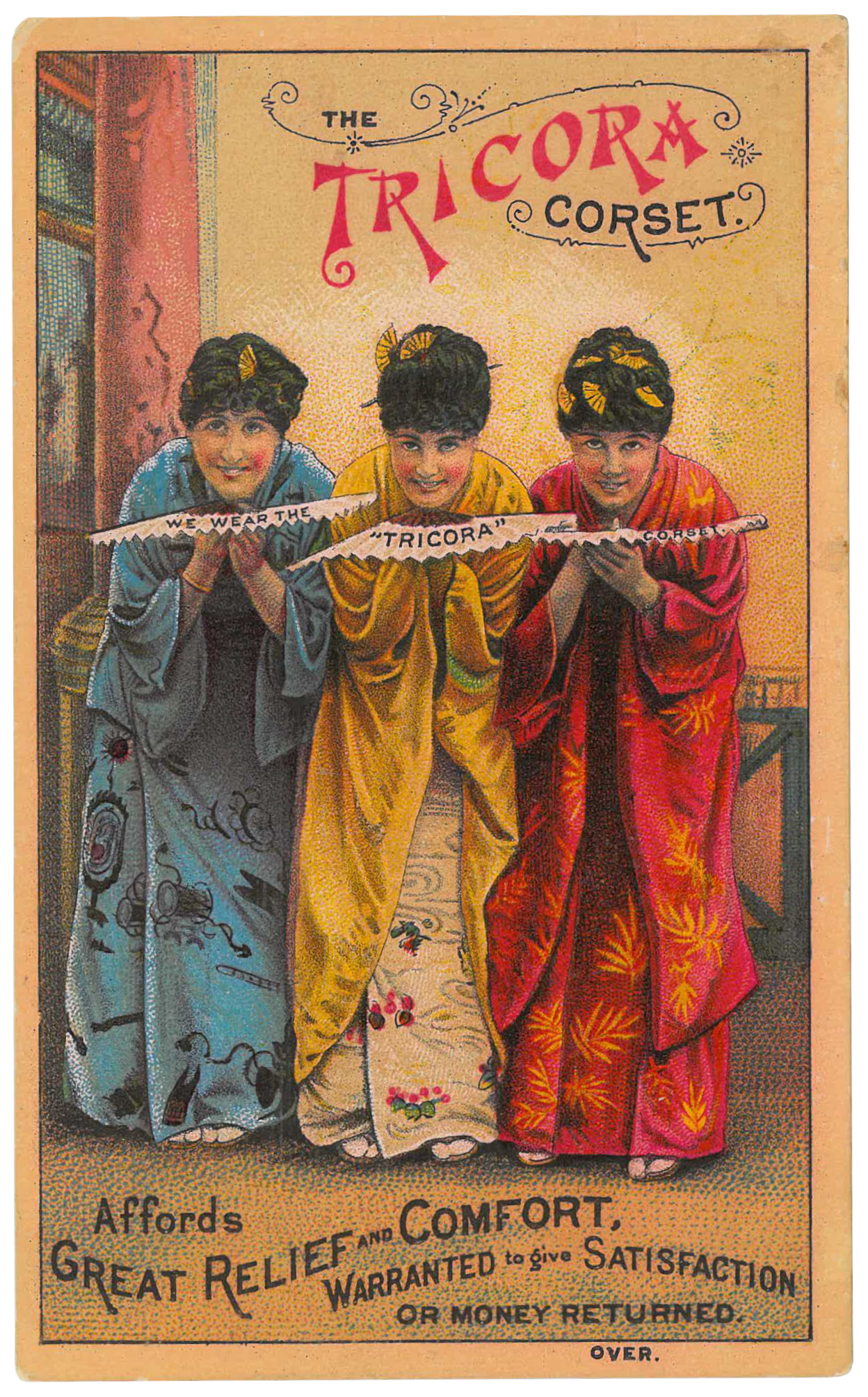

By the Victorian era, assembly line industrialization made many goods more affordable and trade cards helped promote products like women’s corsets to broader audiences. The Tricora corset was marketed as “waterproof, pliable, supporting and absolutely unbreakable.” Yet, rather than showing the corset’s construction, this card features three women dressed in traditional Japanese robes to endorse the product.

Most viewers would have recognized the women in yellowface from the satirical comedic opera, The Mikado, which premiered to popular acclaim in Europe and America in 1885. During performances, the “Three Little Maids” take short shuffle steps and wave hand fans in a synchronized manner, theatrical inventions that became a visual shorthand for signifying Japanese women. The card here depicts a moment of Three Maids’ performative dance which was re-illustrated and satirized across a wide variety of Victorian advertising media.

The Mikado was also set within a world filled with Japanese fans, swords, and vases, making this imaginary Japan inseparable from the commodities it produced and furthering the Japan Craze. For the Victorian consumer, Japan was not a place of real people, but a collection of beautiful objects that could help create a fantasy land inside one’s private parlor room. Moreover, the Mikado provided Americans a reference to dress in yellowface, as is seen in the late Victorian photograph on display. Japanese cultural identity was reduced into a costume.

To consider:

- Why was it “fashionable” to dress up as a Japanese character, while the US government was simultaneously passing laws to exclude Asian immigrants from entering the country?

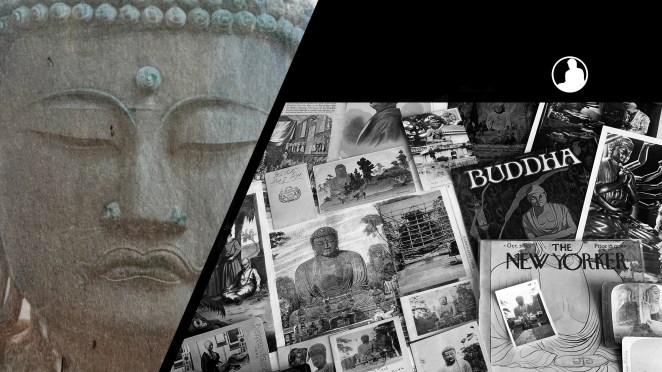

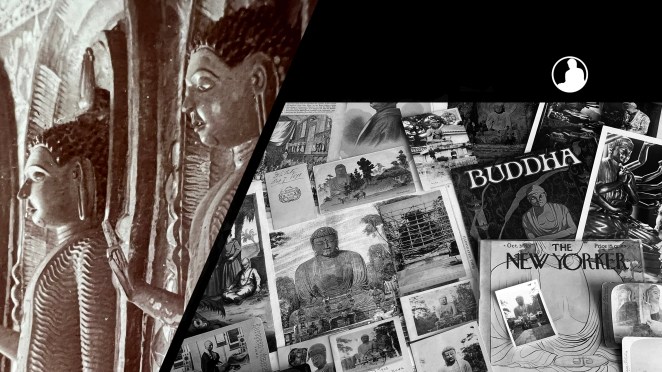

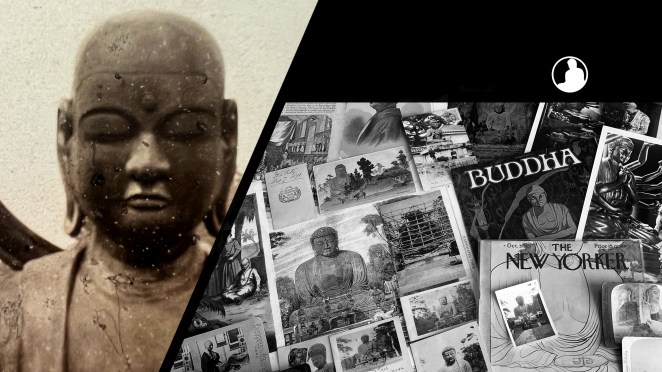

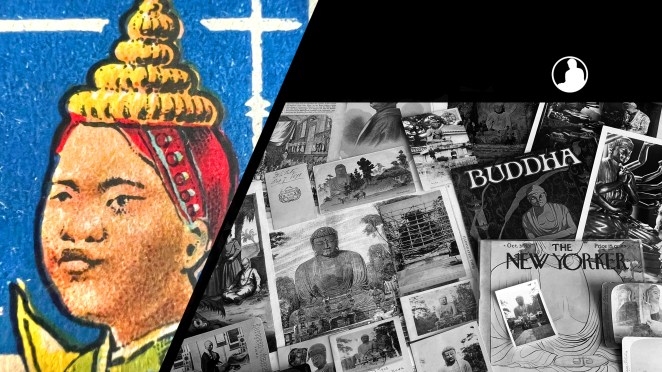

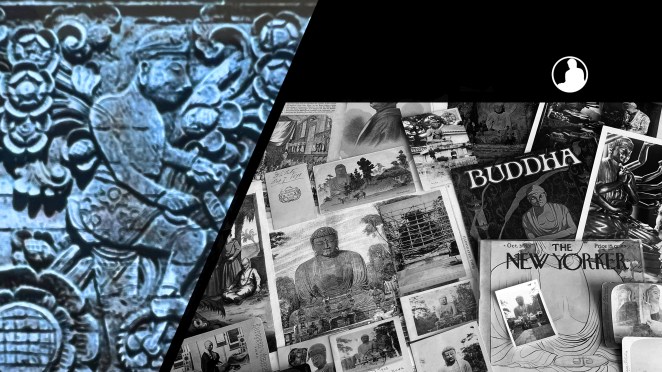

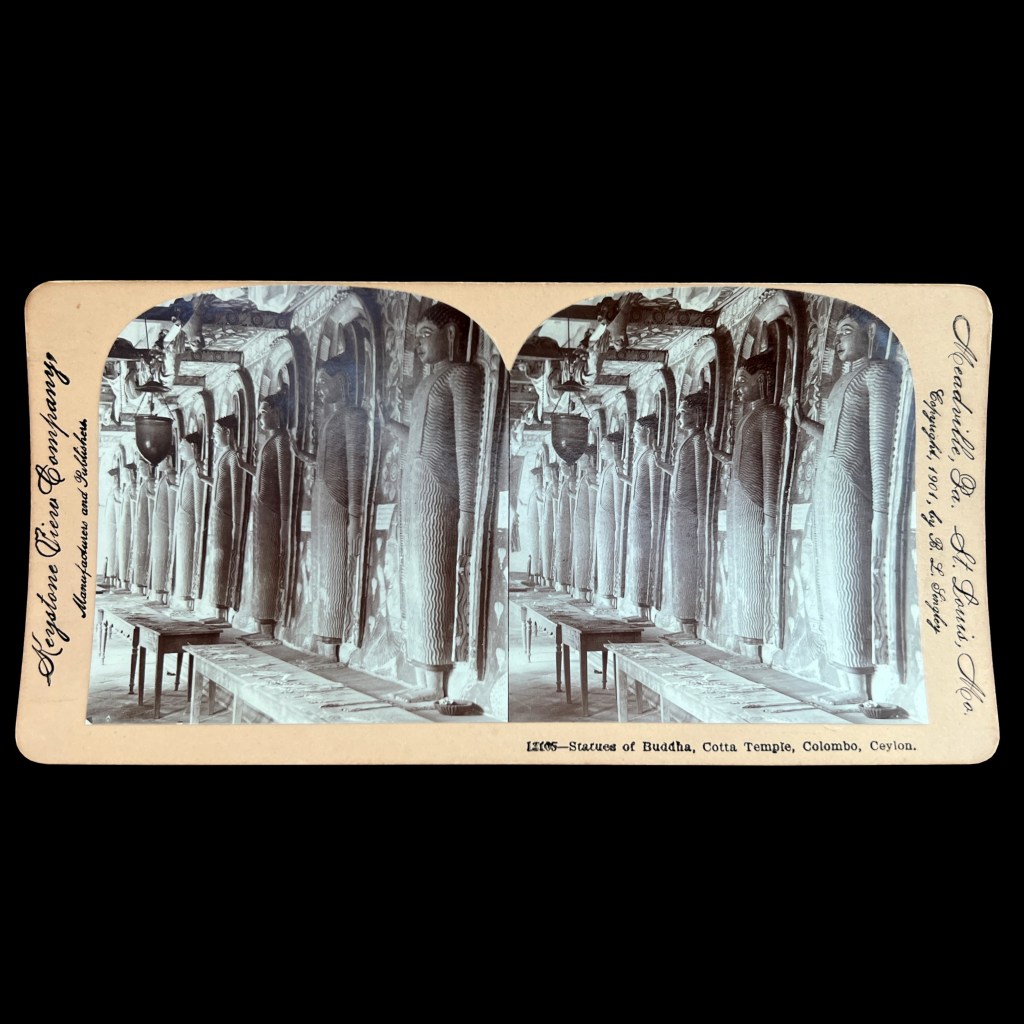

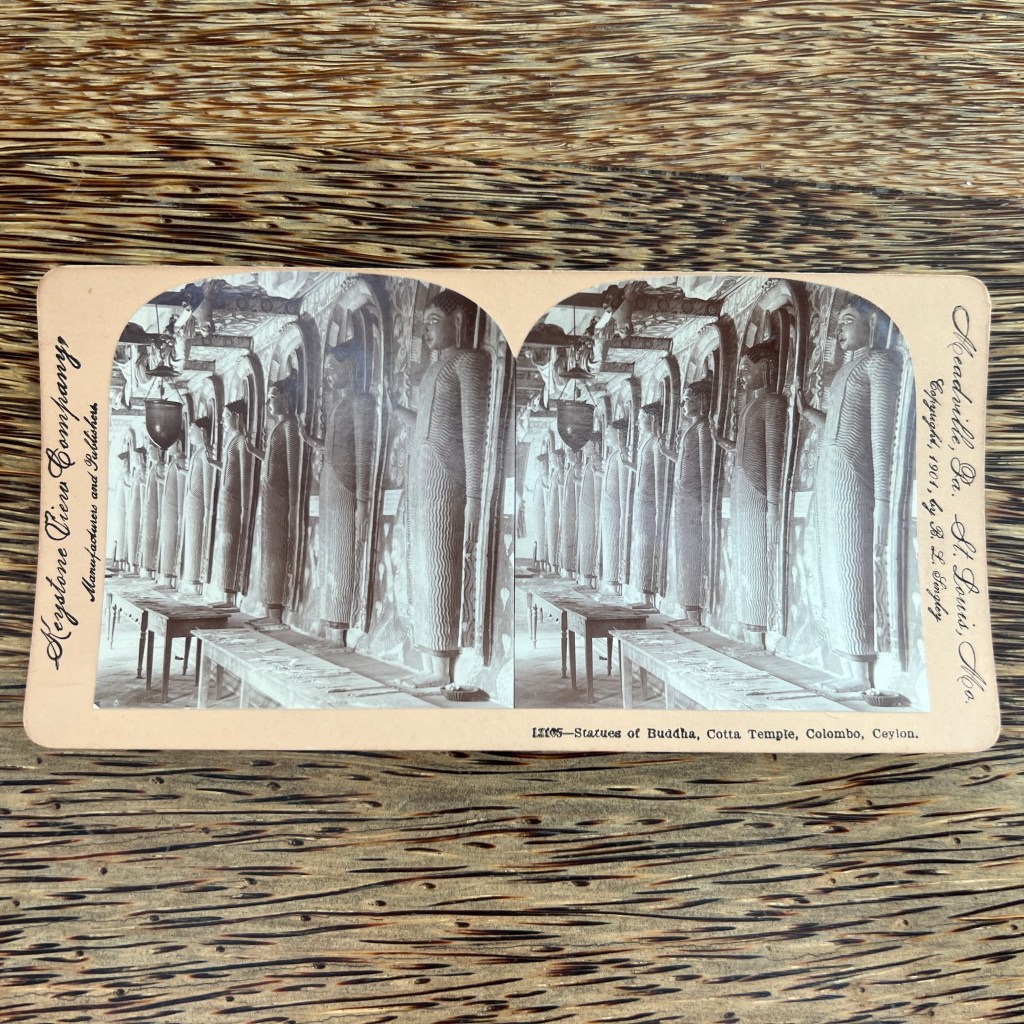

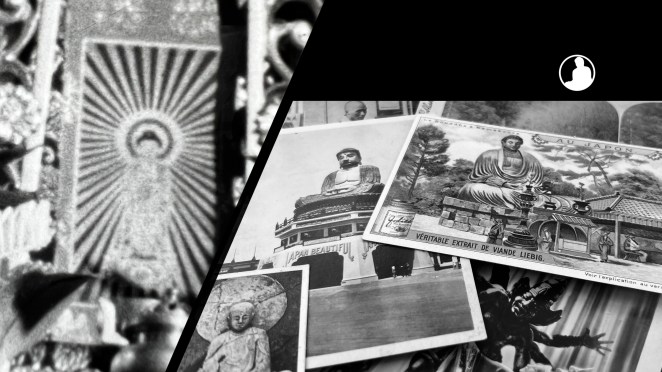

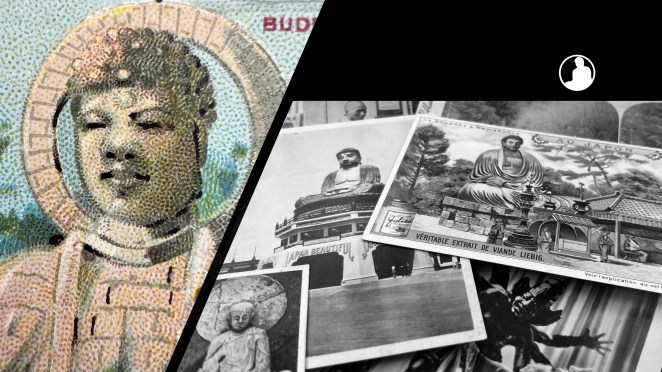

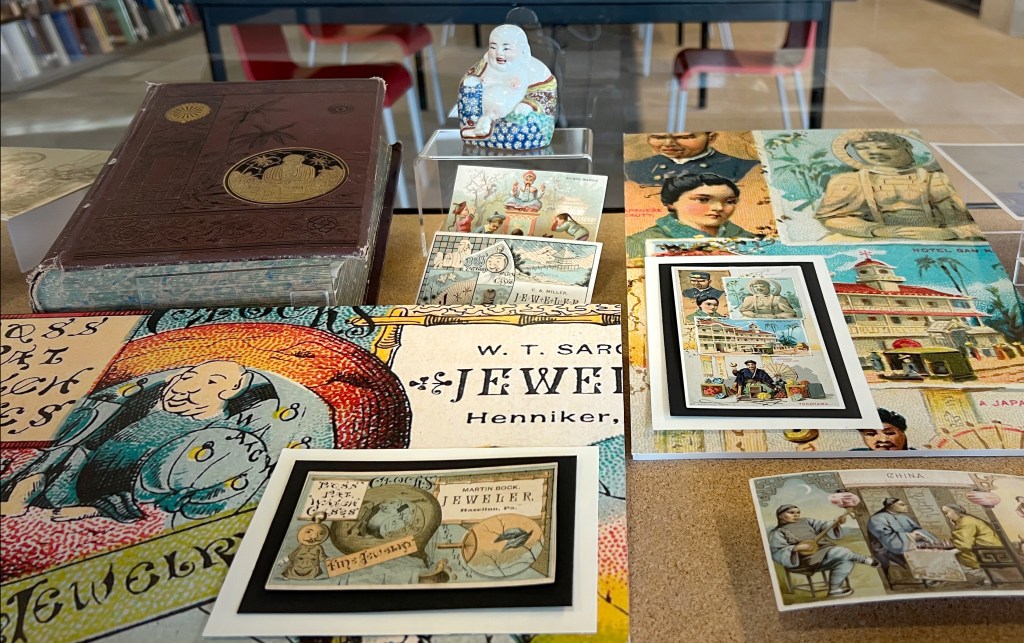

Key Card 5: Buddhist Vogue (1880s)

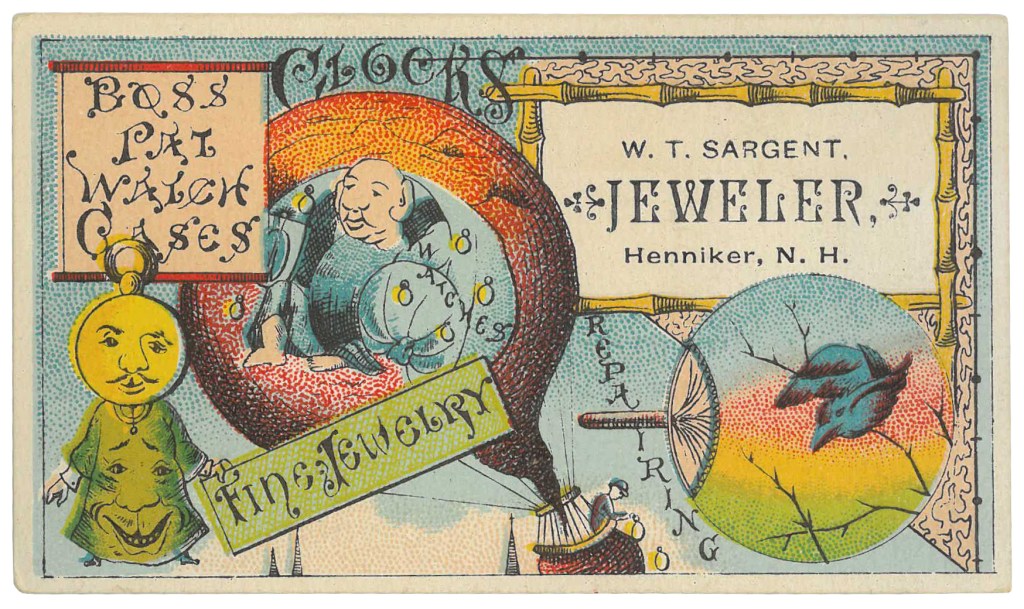

Boss Patent Watch Cases, known for making gold-filled pocket watches, commissioned a set of twelve trade cards bearing a constellation of different Asian motifs. These were designed to be overprinted with retailer’s information for use as business cards.

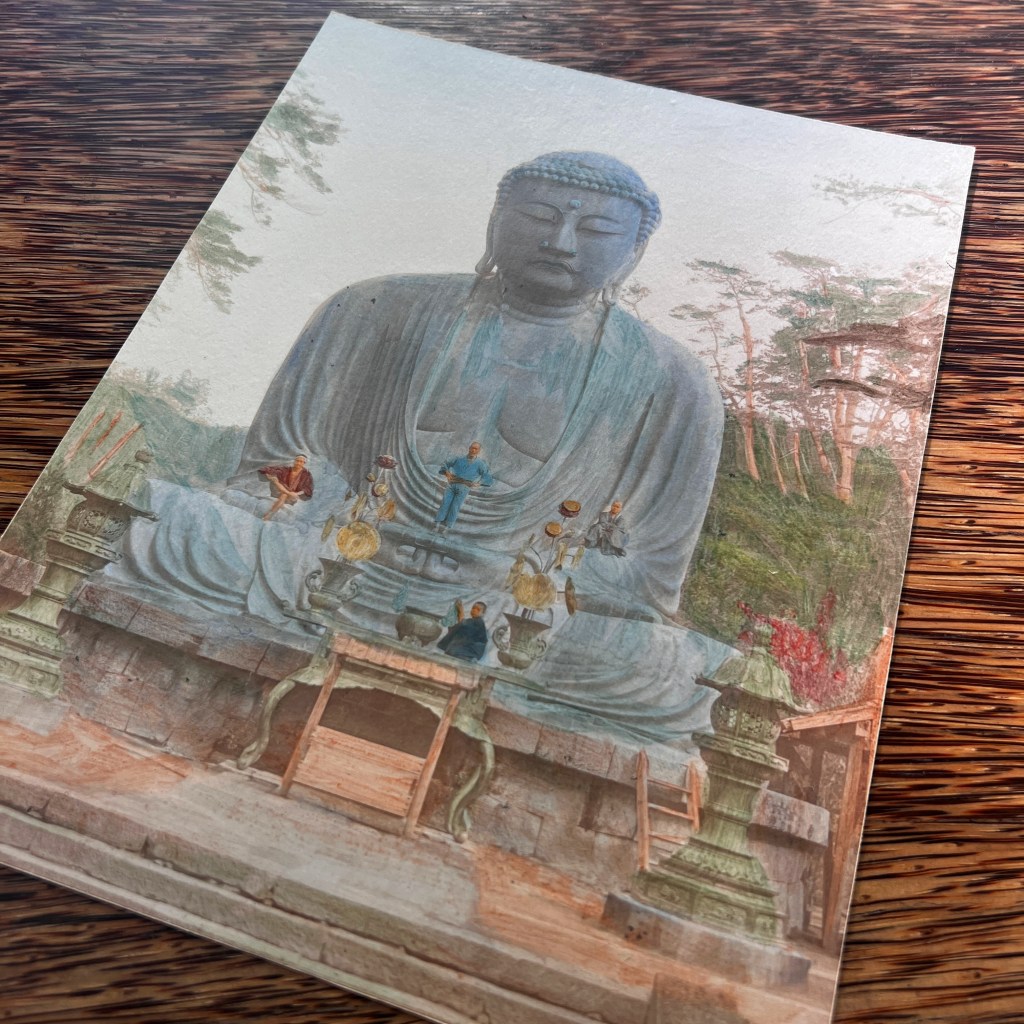

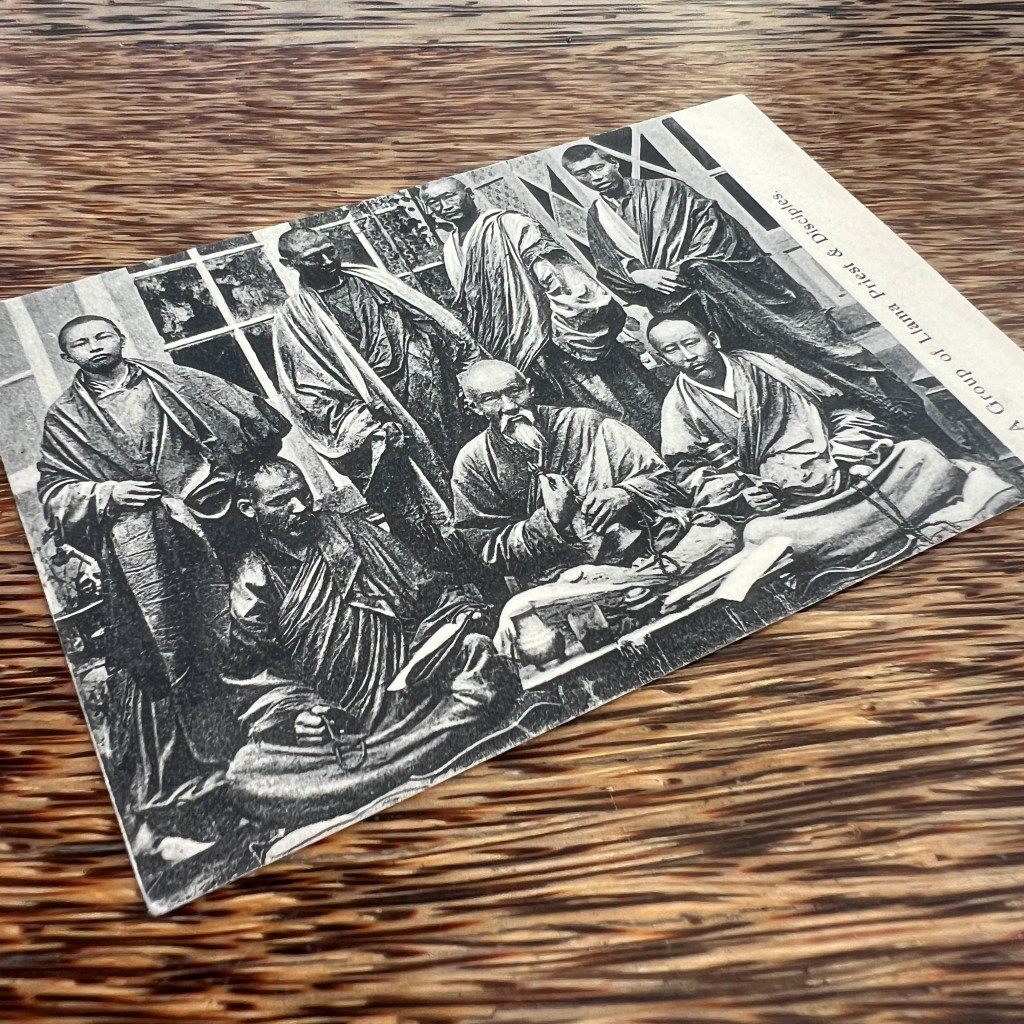

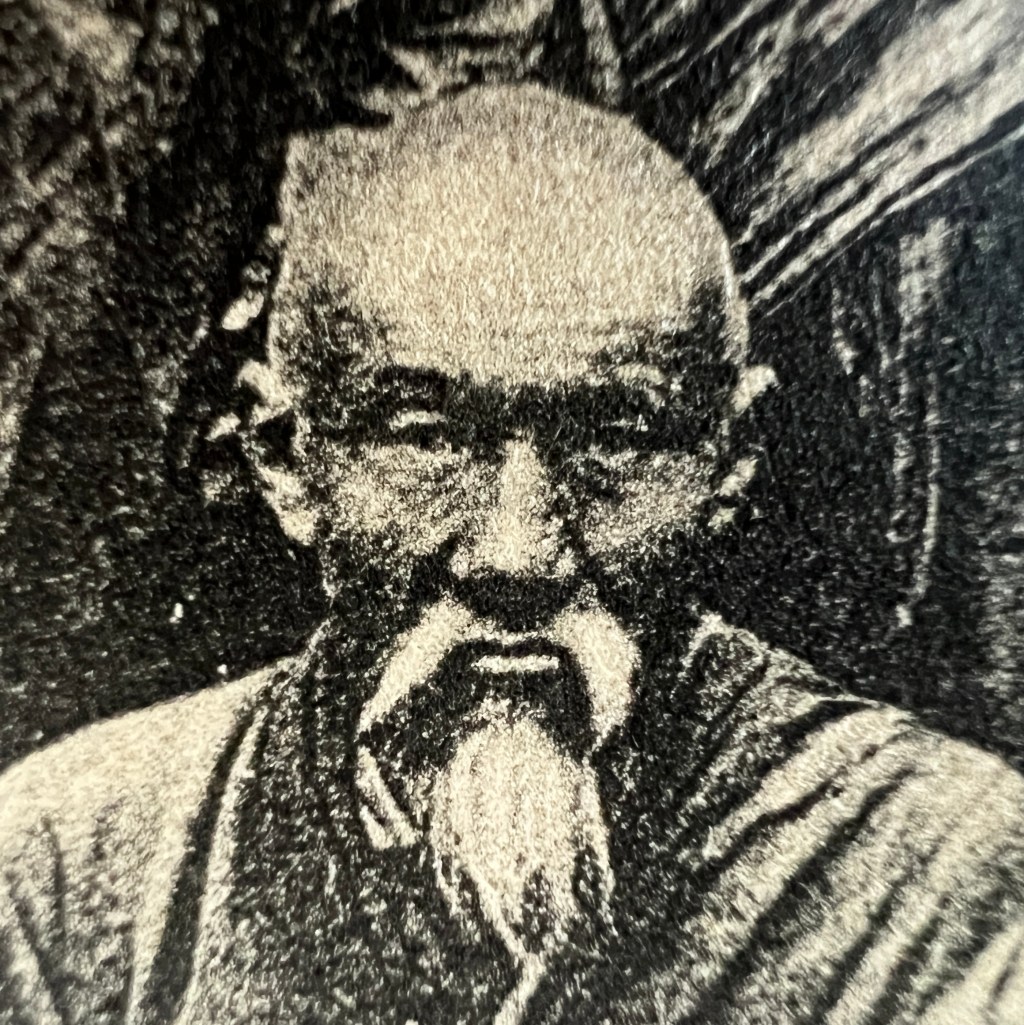

One of the cards depicted a Laughing Buddha superimposed over a hot-air balloon. Despite the growing popularity of Buddhism following the publication of Edwin Arnold’s epic poem, The Light of Asia, in 1879, this Laughing Buddha is not treated with religious reverence. Small statues of the Laughing Buddha, similar to the one on display, circulated as relatively affordable decorative trinkets from Asia and were more likely placed atop a fireplace mantle than placed in a household shrine. Moreover, note how several slightly off-register yellow watches adorn the Laughing Buddha’s robes, turning him into a walking billboard.

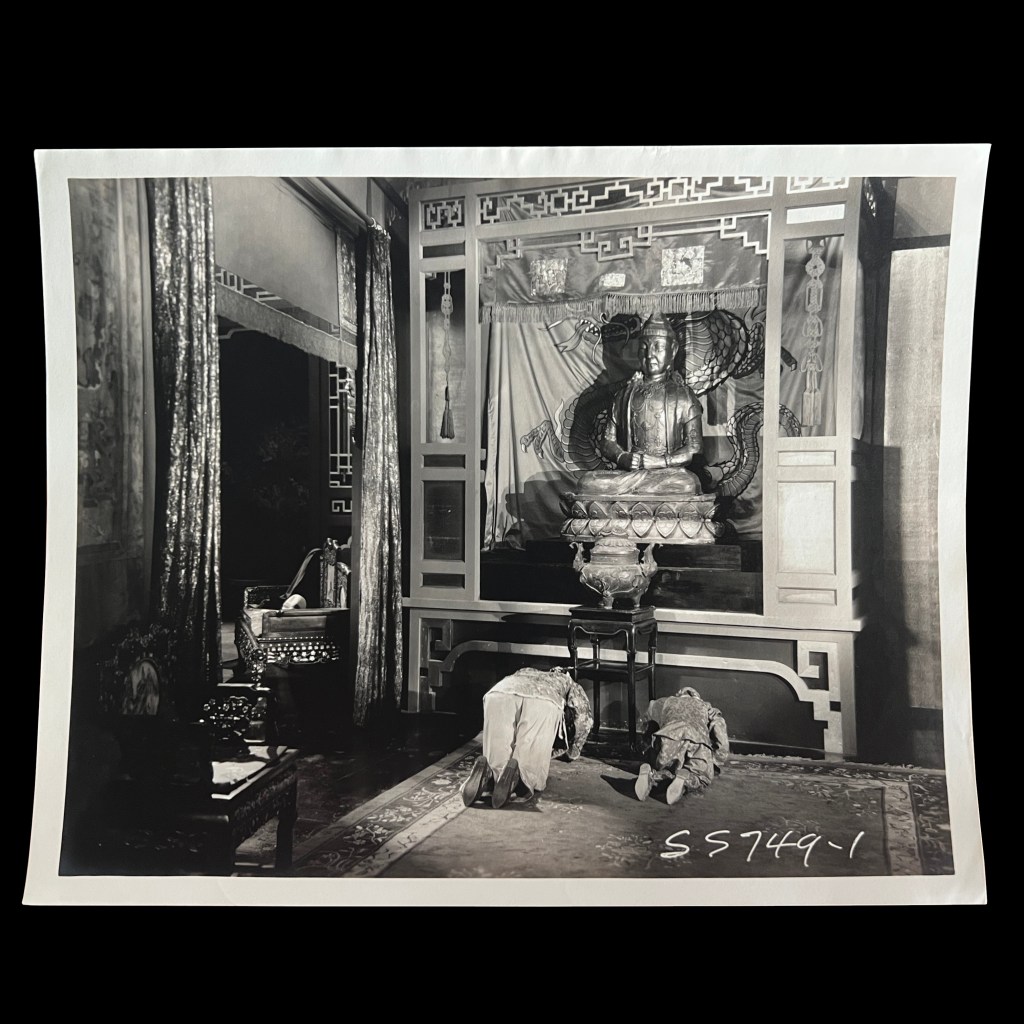

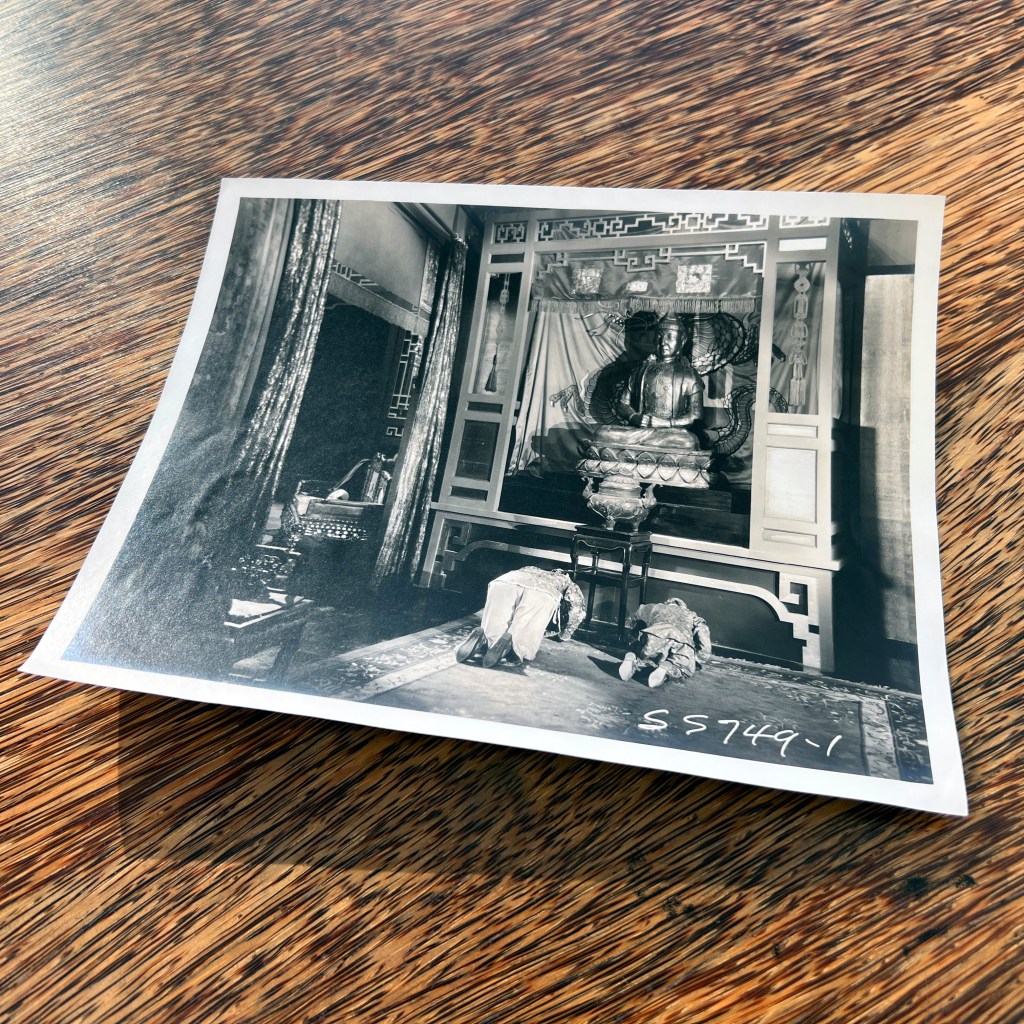

Alternatively, when Buddhist statues were not treated decorative curios, but depicted as the focus of religious worship, they were often portrayed as dangerous idols. As seen with the other two cards on display, these Buddhist icons were depicted as devil-like beings or as having exaggerated racial characteristics, symbolic of foreign danger.

To consider:

- What happens to a religion when its sacred icons become commodified “marketing mascots” or household decoration?

Key Card 6: Globetrotting Asia (1890s)

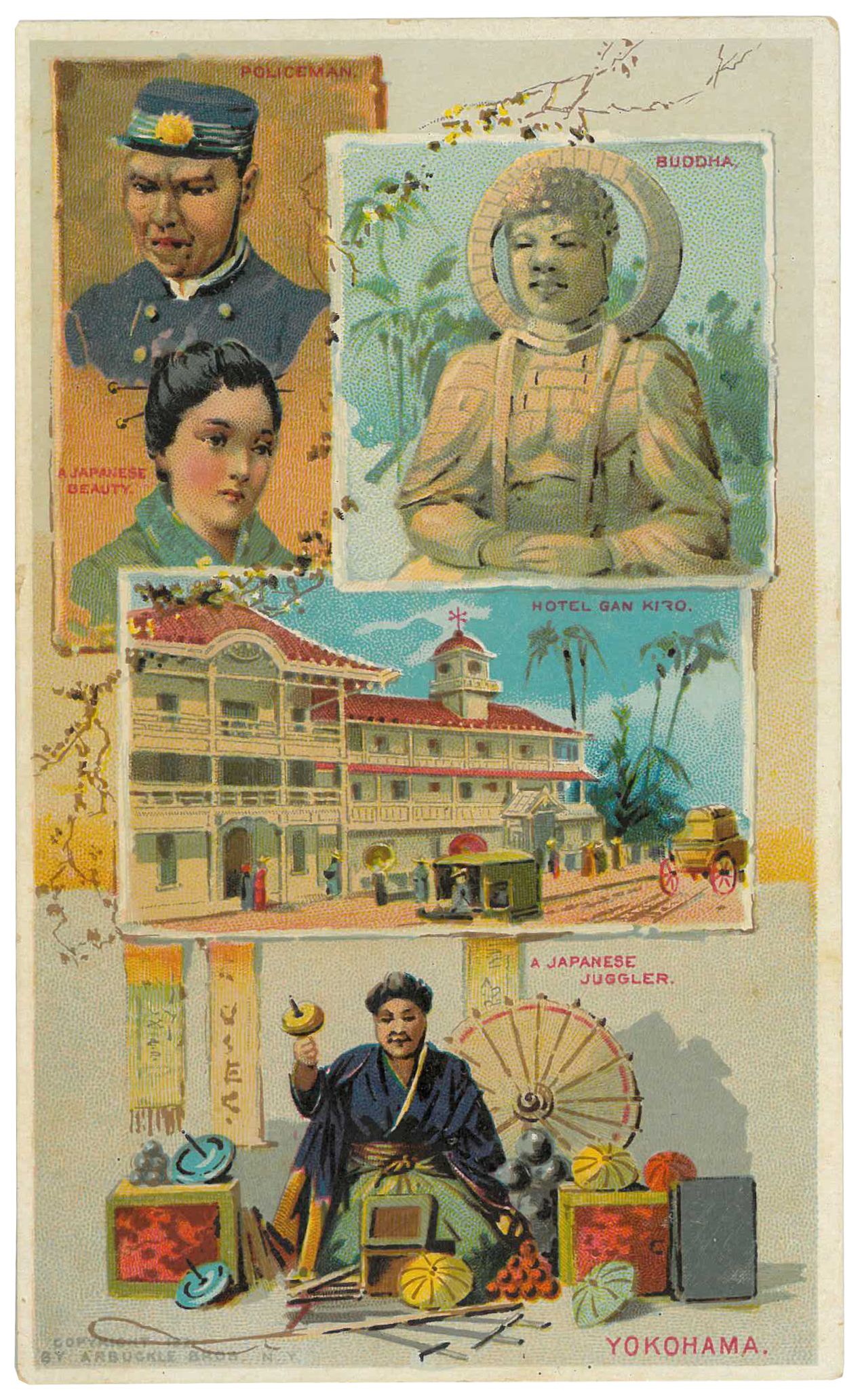

The Arbuckle Brothers, renowned for marketing a variety of pre-roasted coffee beans, began inserting colorful trade cards into its packaging in the mid-to-late 1880s. The firm was among the first American companies to organize such cards into numbered series designed to form complete collectible sets. These included National Geographical World Atlas (50 cards, 1889), A Trip Around the World (50 cards, 1891), and Sports and Pastimes of All Nations (50 cards, 1893).

This emphasis on comparing and collecting cultures from across the globe reflected contemporary advances in travel technology and the opening of new international routes. The completion of the American transcontinental railroad in 1868, followed by the opening of the Suez Canal the following year, offered wealthy tourists unprecedented opportunities to circumnavigate the world in less than three months.

This card depicting Yokohama, Japan, comes from Arbuckle’s Trip Around the World series. Yokohama was the main port of entry into Japan after crossing the Pacific Ocean from the West Coast. The lithographer, New York-based Joseph P. Knapp, selected stereotypical imagery to depict the Japanese port city, including a juggler, a Buddha statue, and a kimono clad “Japanese Beauty.” The central structure, however, was not a hotel but the Gankirō Teahouse, an establishment in the pleasure quarter that served both foreign visitors and Japanese patrons.

To consider:

- What visual elements found on this Arbuckle trade cards appear elsewhere in this exhibit?

Further Readings

Lee, Erika. 2016. The Making of Asian America: A History. Simon & Schuster. [San Diego Central Library]

Luo, Michael. 2025. Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America. Doubleday.

Okihiro, Gary Y. 2001. The Columbia Guide to Asian American History. Columbia University Press. [San Diego Central Library]

Takaki, Ronald. 1998. Strangers From a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Little, Brown and Company. [San Diego Central Library]

Keevak, Michael. 2011. Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking. Princeton University Press.

Lee, Josephine D. 2010. The Japan of Pure Invention: Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado. University of Minnesota Press.

Moy, James S. 1993. Marginal Sights: Staging the Chinese in America. University of Iowa Press.

Ngai, Mae. 2021. The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics. W.W. Norton & Co. [San Diego Central Library]

Schodt, Frederik L. 2012. Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe: How an American Acrobat Introduced Circus to Japan—and Japan to the West. Stone Bridge Press.

Sueyoshi, Amy Haruko. 2018. Discriminating Sex: White Leisure and the Making of the American “Oriental.” University of Illinois Press.

Suh, Chris. 2023. The Allure of Empire: American Encounters with Asians in the Age of Transpacific Expansion and Exclusion. Oxford University Press.

William, Duncan Ryūken. 2019. American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War. Harvard University Press. [San Diego Central Library]

Appel, John, and Selma Appel. 1991. “Sino-Phobic Advertising Slogans: ‘The Chinese Must Go.’” Ephemera Journal 4: 35–40.

Beckman, Thomas. 1996. “Japanese Influences on American Advertising Card Imagery and Design, 1875–1890.” Journal of American Culture 19 (1): 7–20.

Cheung, Floyd. 2007. “Anxious and Ambivalent Representations: Nineteenth‐Century Images of Chinese American Men.” The Journal of American Culture 30 (3): 293–309.

Matsukawa, Yukio. 2002. “Representing the Oriental in Nineteenth-Century Trade Cards.” In Re/Collecting Early Asian America: Essays in Cultural History, edited by Josephine D. Lee, Imogene L. Lim, and Yuko Matsukawa. Temple University Press.

Metrick-chen, Lenore. 2007. “The Chinese of the American Imagination: 19th Century Trade Card Images.” Visual Anthropology Review 23: 115–36.

Metrick-Chen, Lenore. 2013. “Class, Race, Floating Signifier: American Media Imagine the Chinese, 1870-1900.” In Race and Racism in Modem East Asia: Western and Eastern Constructions, edited by Rotem Kowner and Walter Demel. Brill.

Kim, Elizabeth. 2002. “Race Sells: Racialized Trade Cards in 18th-Century Britain.” Journal of Material Culture 7 (2): 137–65.

Kim, Sue. 2008. “The Dialectics of ‘Oriental’ Images in American Trade Cards.” Ethnic Studies Review 31 (2): 1–34.

Schröder, Nicole. 2012. “Commodifying Difference: Depictions of the ‘Other’ in Nineteenth-Century American Trade Cards.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 34: 85–115.

[Digital Exhibit] Trade Cards: An Illustrated History–Highlights from the Waxman Collection [Cornell University Library]

[Digital Exhibit] Victorian Ephemera [Brandeis University]

[Digital Collection] Advertising Ephemera [Harvard Business School]

[Digital Collection] Patent Medicine Trade Cards [UCLA Library]

[Digital Collection] Victorian Trade Cards [Iowa University]

Thank you for your visit!

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.