For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

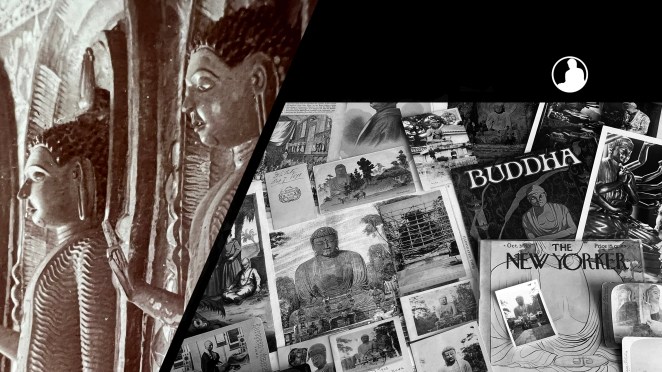

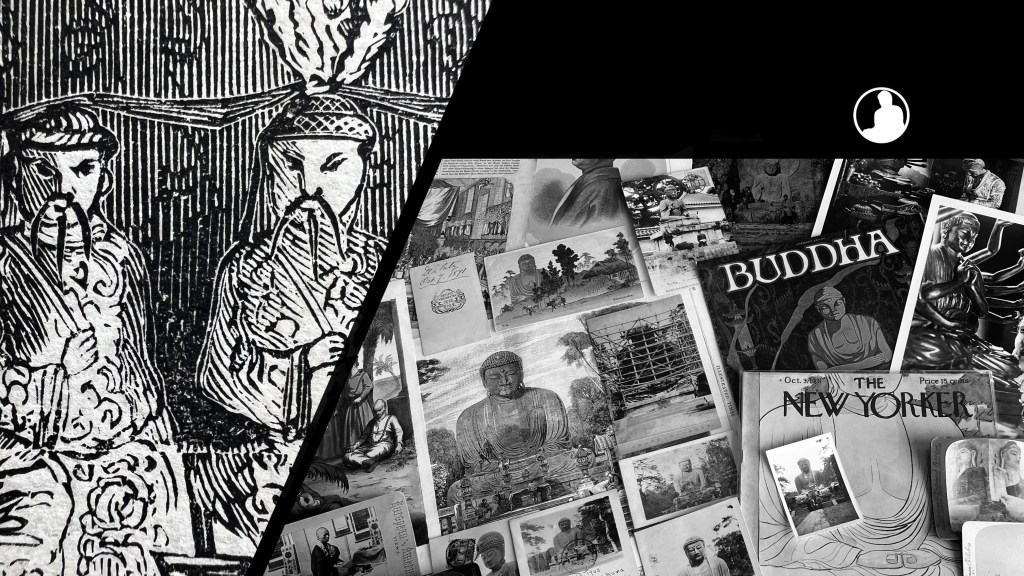

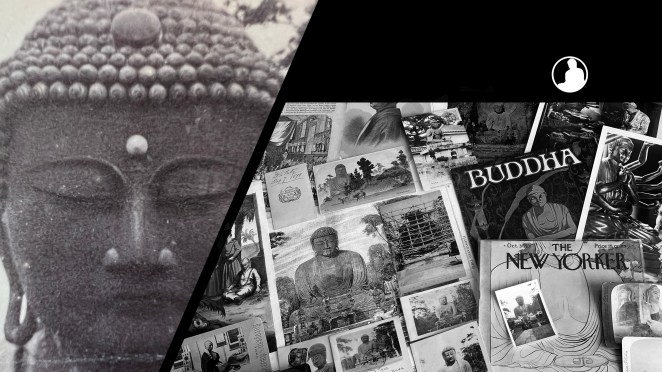

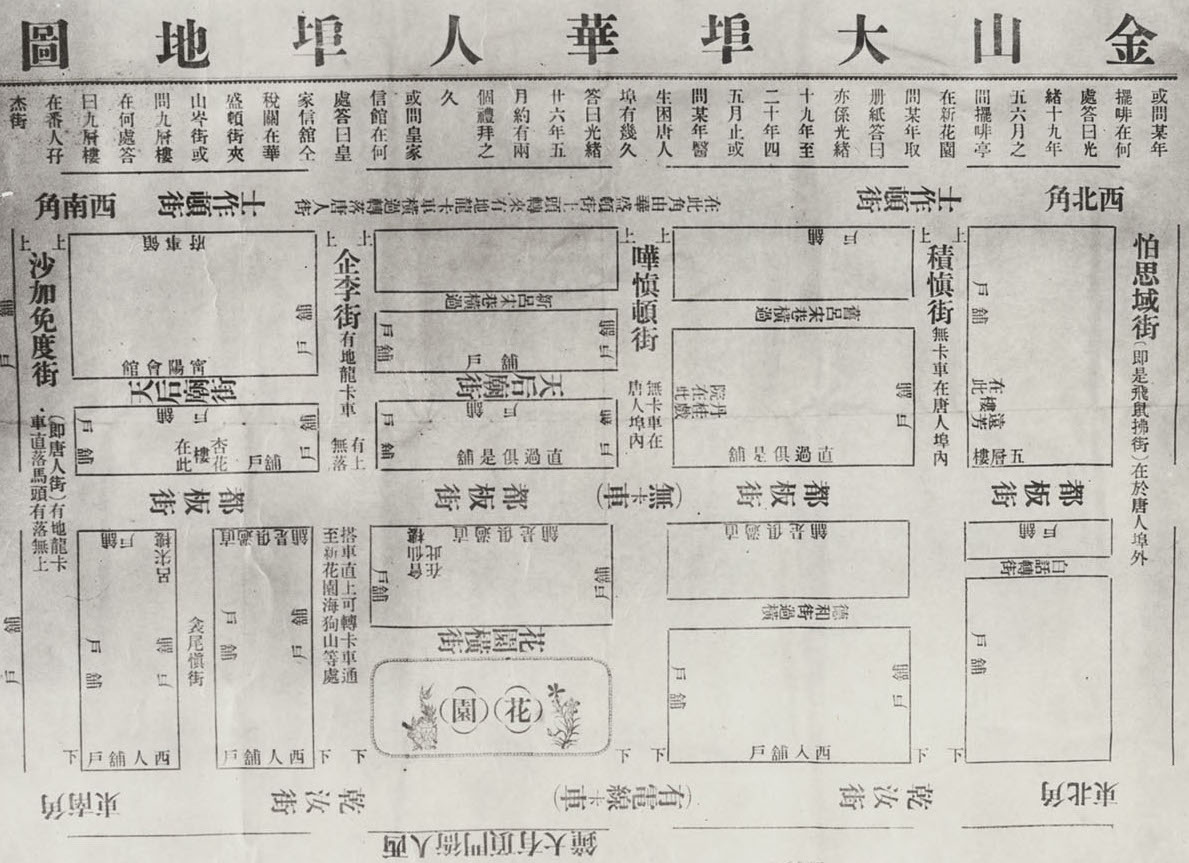

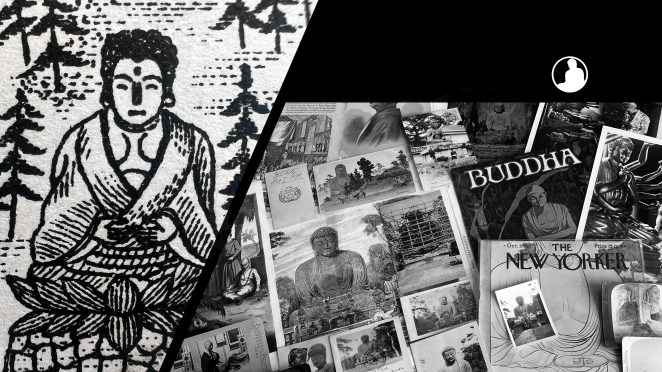

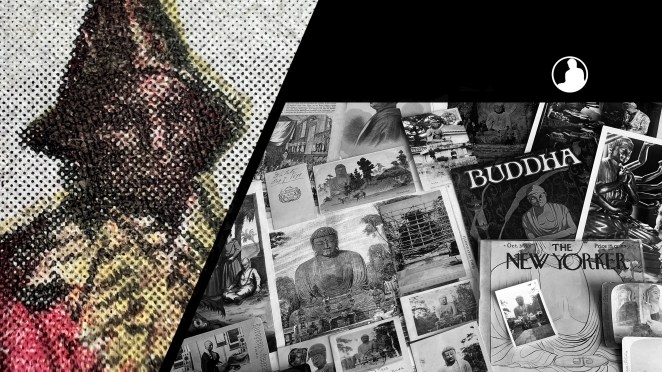

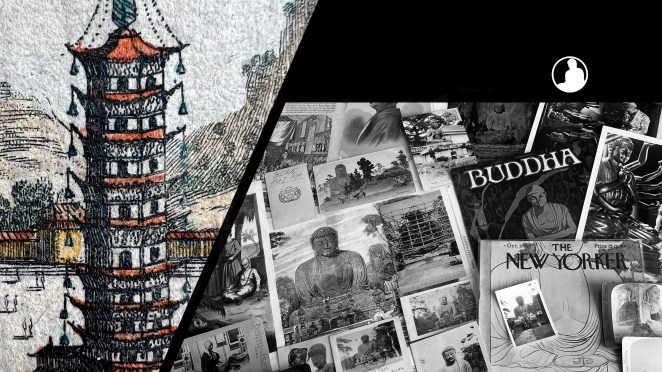

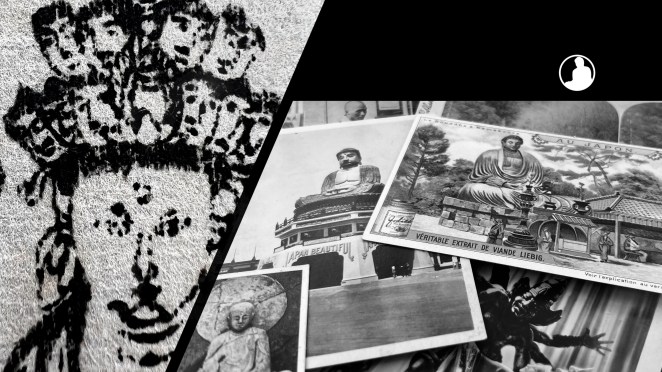

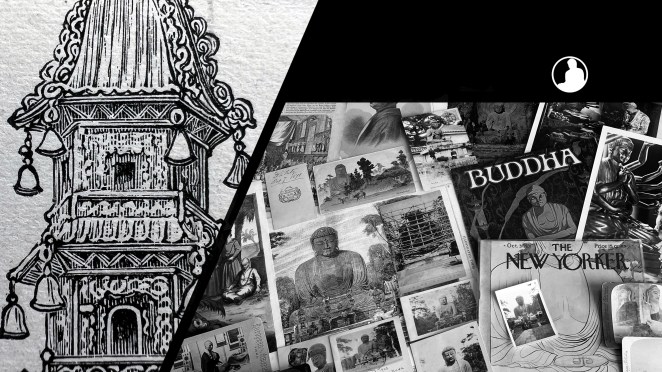

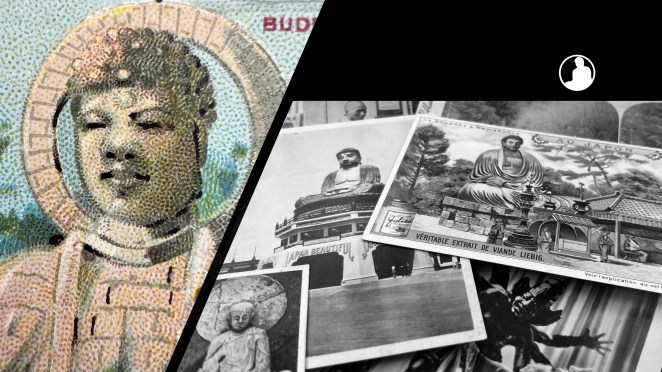

The Atlas Chinensis by Olfert Dapper (1636–1689) is among the most visually embellished European treatments of China from the late 17th century. Never traveling to Asia, Dapper used reports from the 2nd and 3rd Dutch embassies to China and consulted older Jesuit accounts.

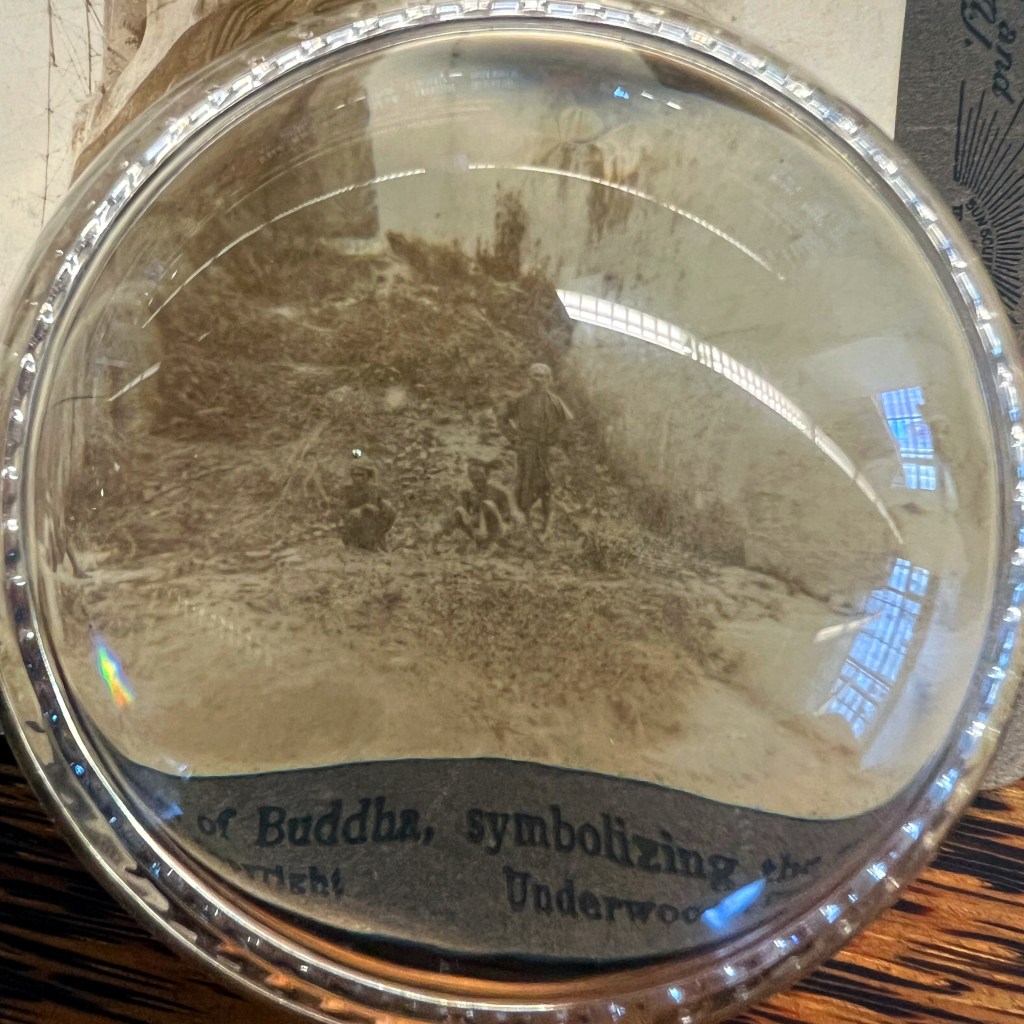

The copperplate engravings were likely prepared in the workshop of publisher Jacob van Meurs who found reasonable success issuing illustrated books on Asia. The illustration here is from the 1674 German edition of Atlas Chinensis; it was originally published in Dutch in 1670.

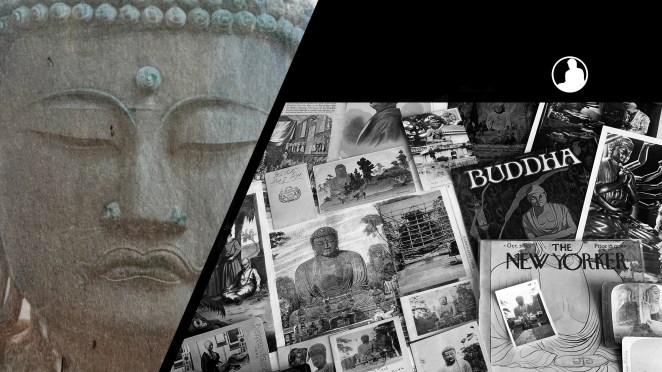

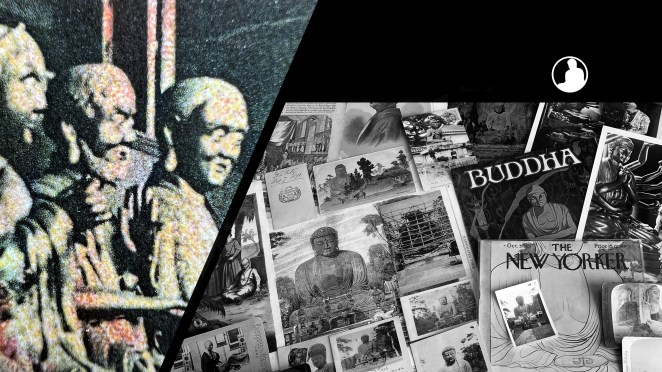

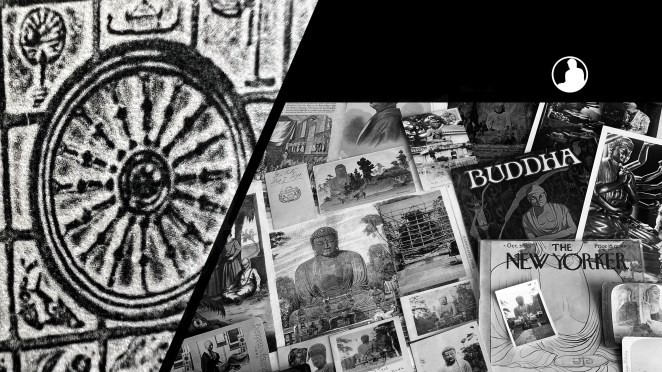

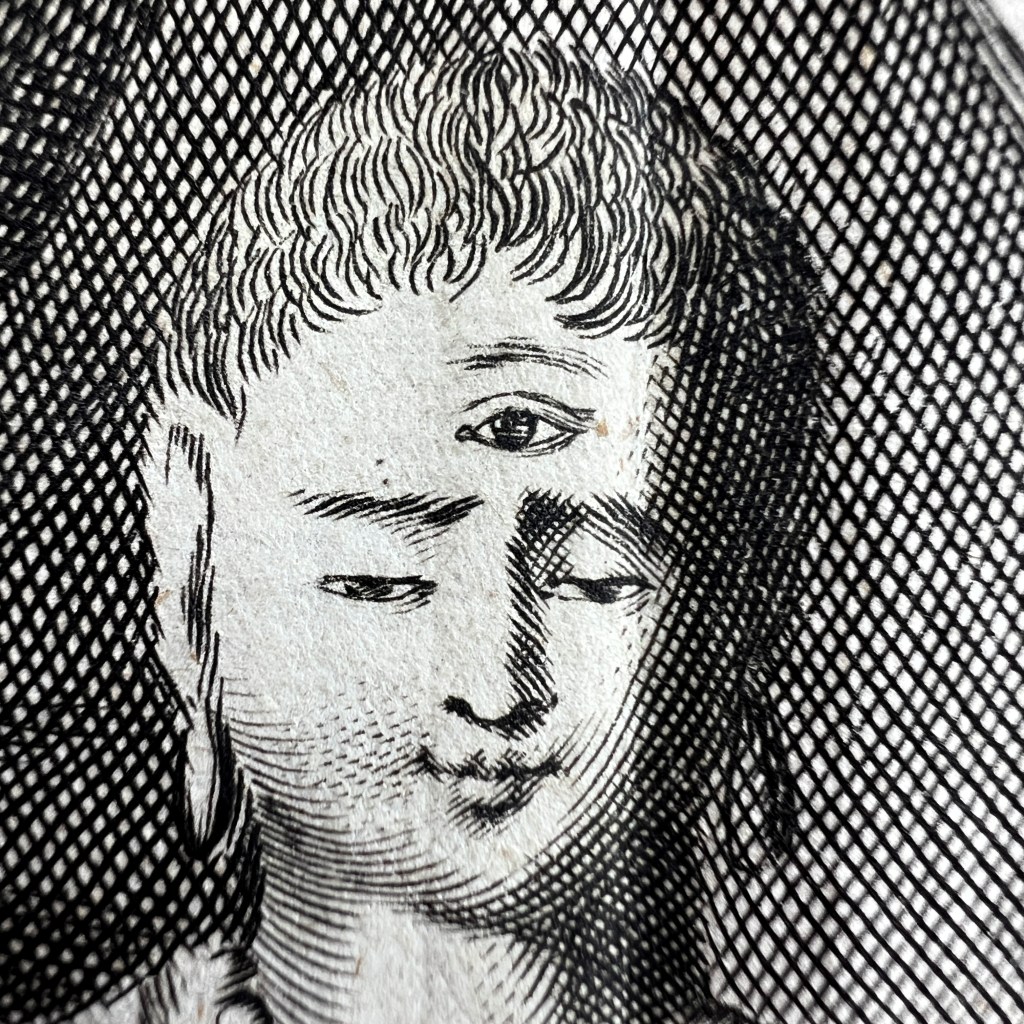

In a section describing Buddhism, Dapper notes that images of the “Idoll Sechia” (Śākyamuni) are found in temples, “in the shape of a fair Youth; with a third Eye in his forehead.” Engravers had great liberty to interpret and add further details.

Some details, such as the European-style crown at the base of the altar, suggest fabricated visual embellishments intended to make the scene more familiar to European readers.

While other details that might appear odd, such as the flanking figures scratching their ears, are actually based on authentic Buddhist imagery of the arhats (C. luohan). Unpublished Jesuit sketches available to Dapper likely informed some of these details.

An English edition of Dapper’s work, published by John Ogilby in 1671 (and curiously misattributed to Arnoldus Montanus), can be viewed through Stanford University here: tinyurl.com/ycyw93eb.

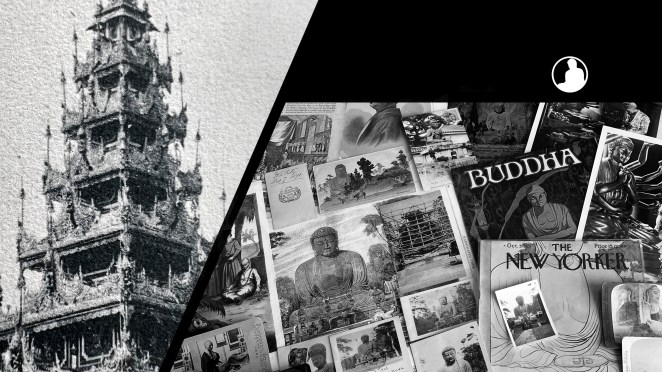

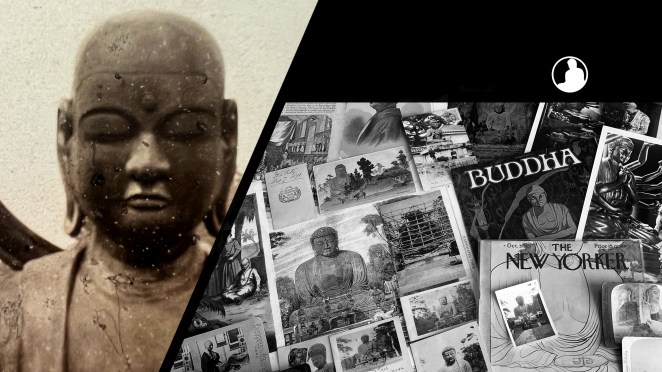

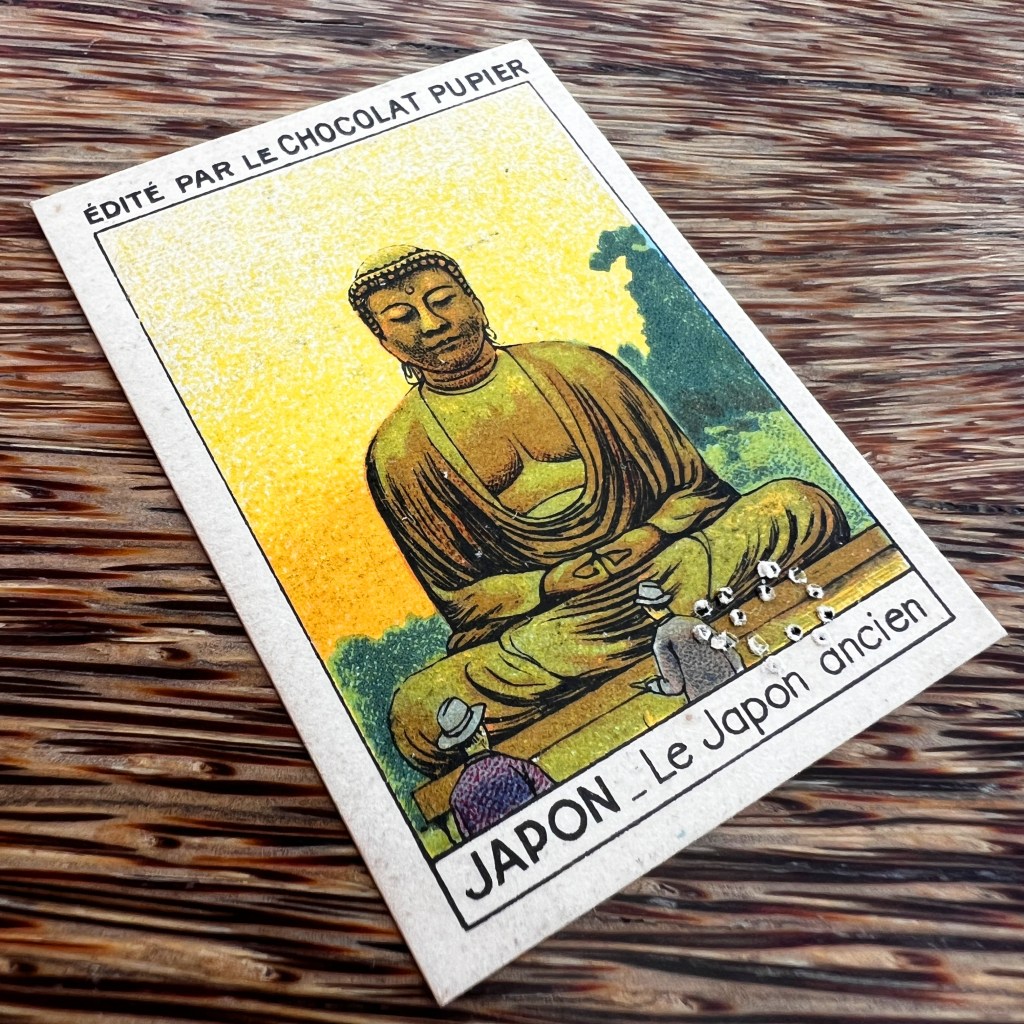

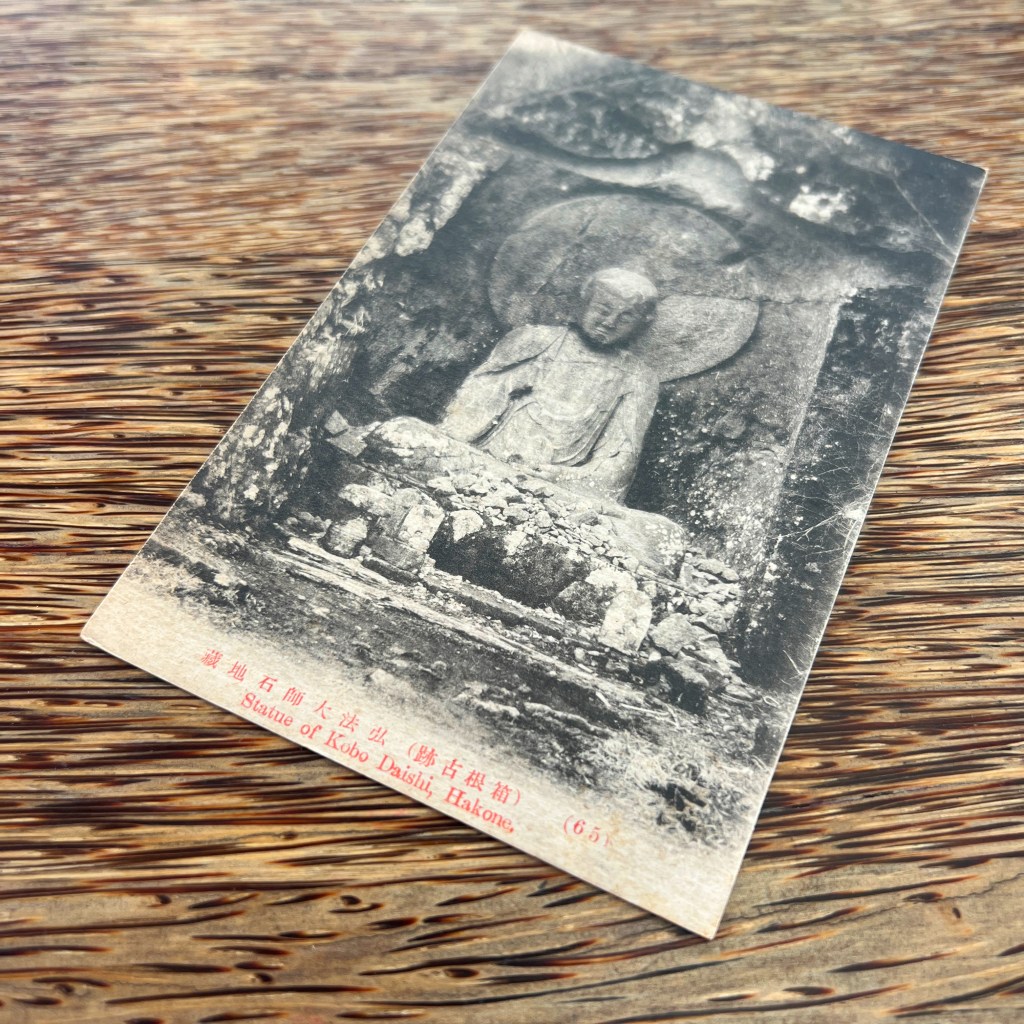

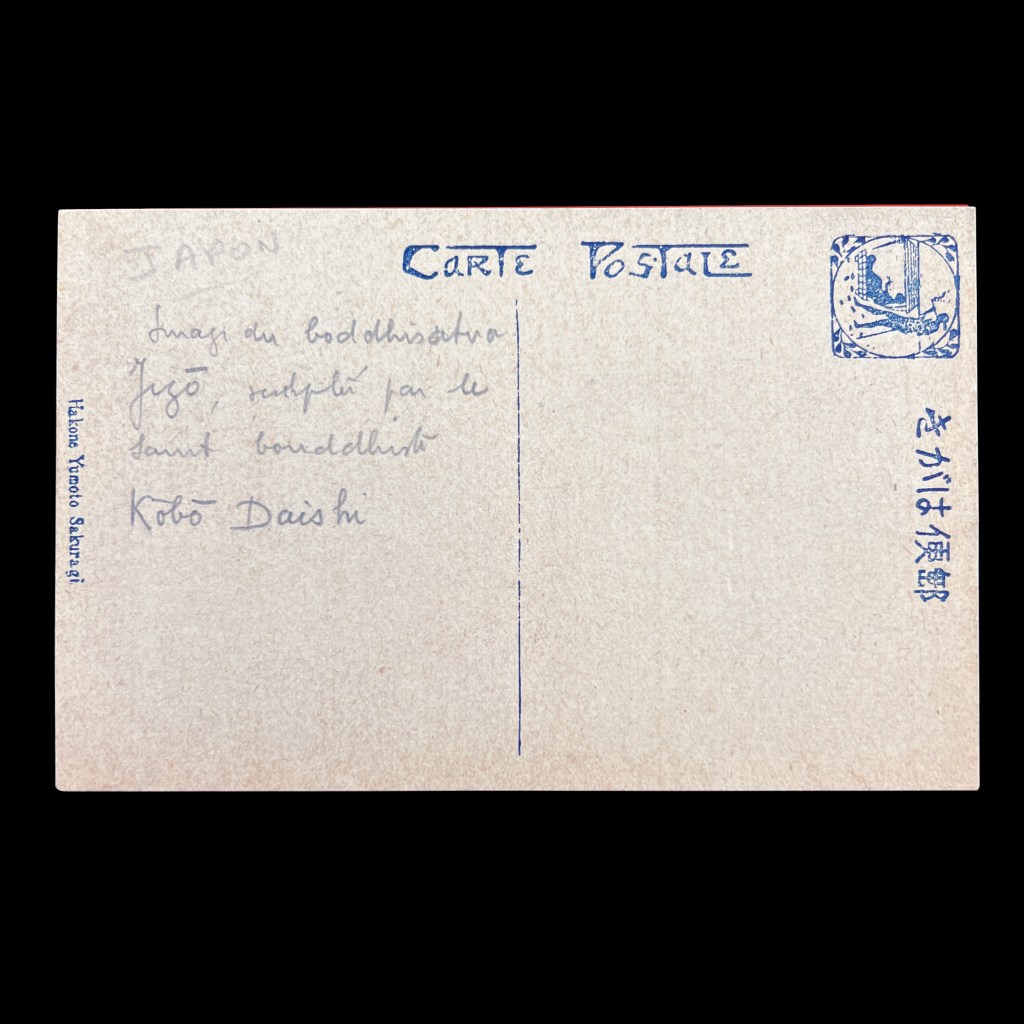

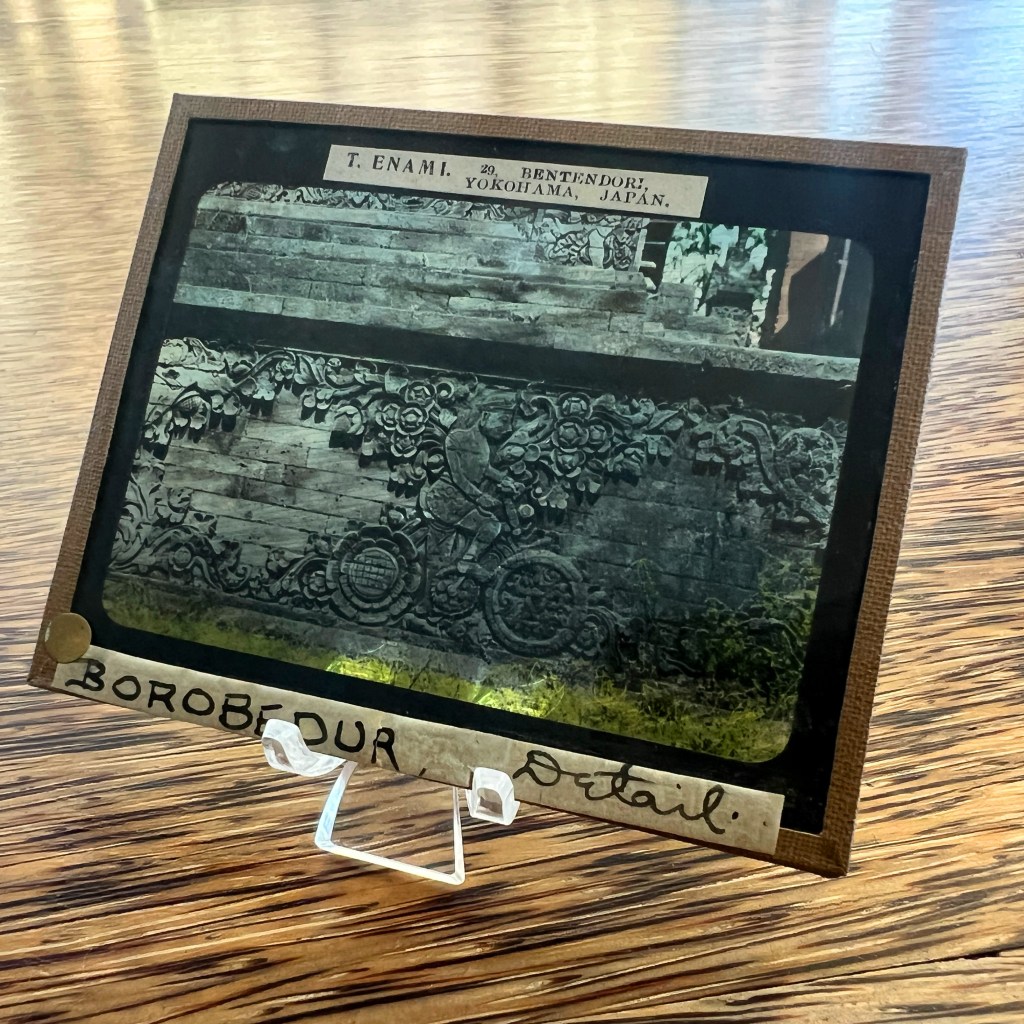

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Historical Engravings:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: