For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

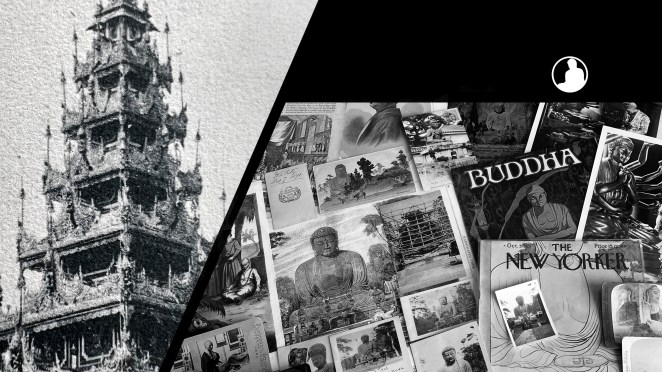

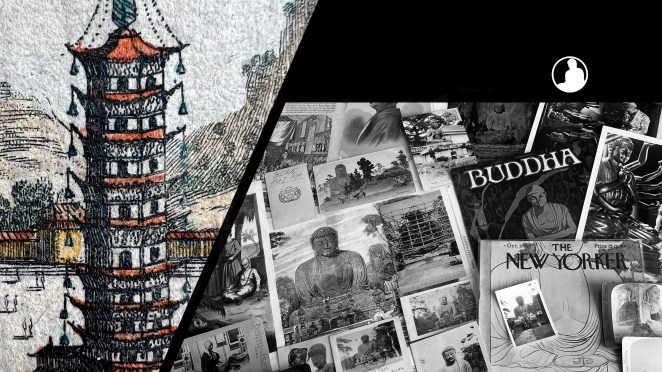

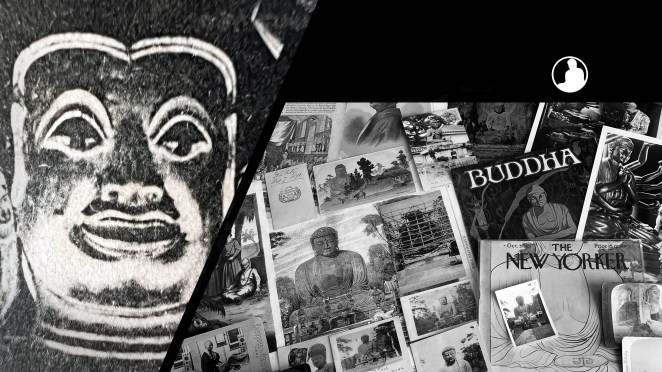

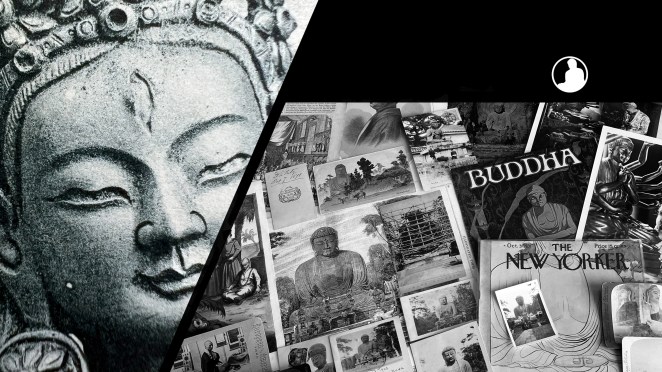

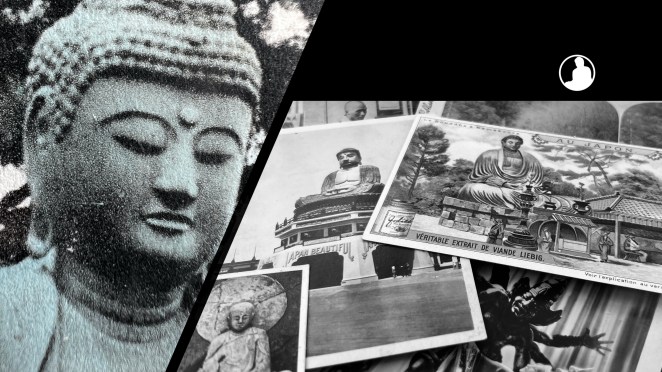

In 1922, the organizers of the Colonial Exposition in Marseille accomplished the impossible – a plaster recreation of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat. While only a partial replica, the central tower, built on a wooden skeleton, was 177 ft. (54m) tall and towered over the exposition grounds.

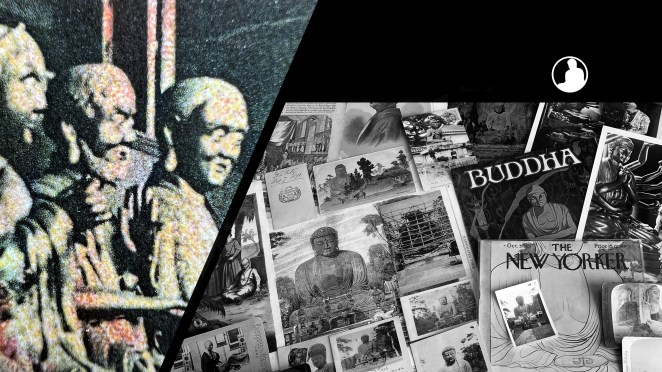

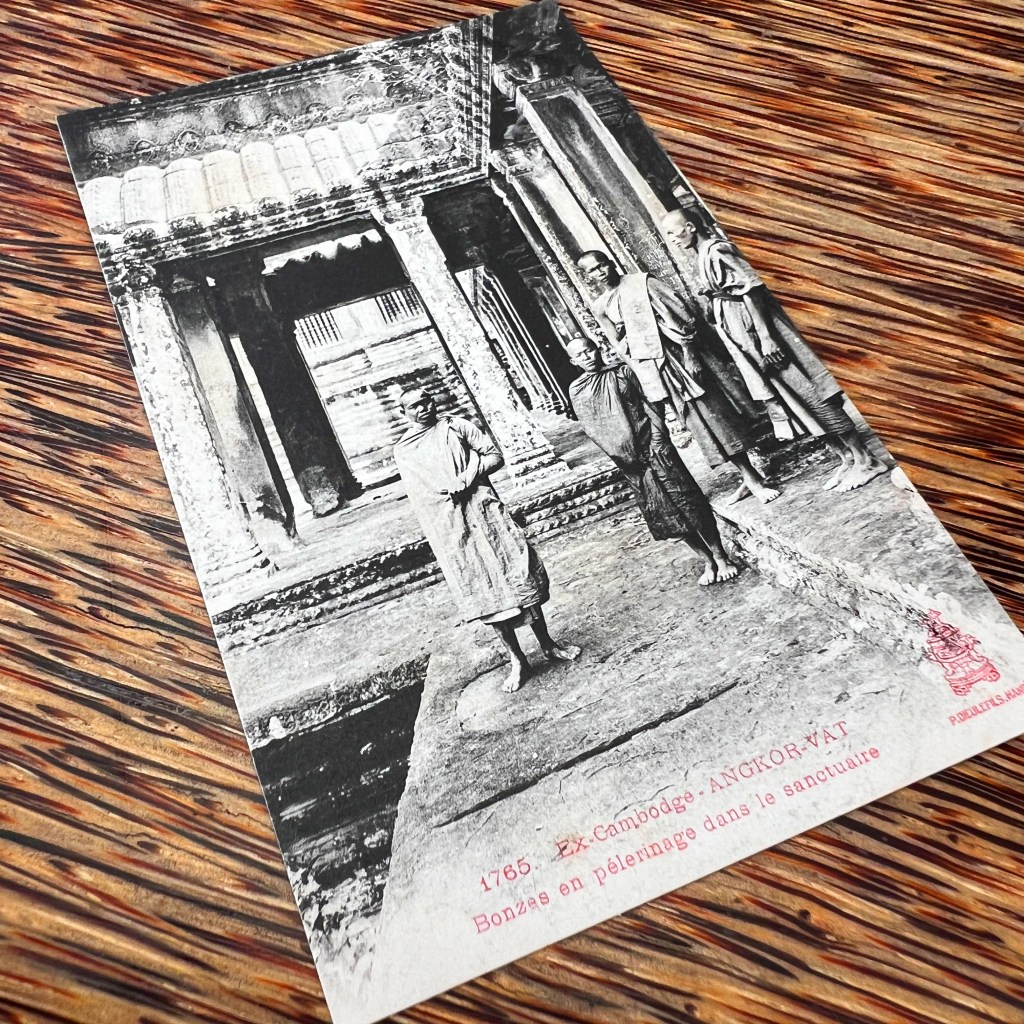

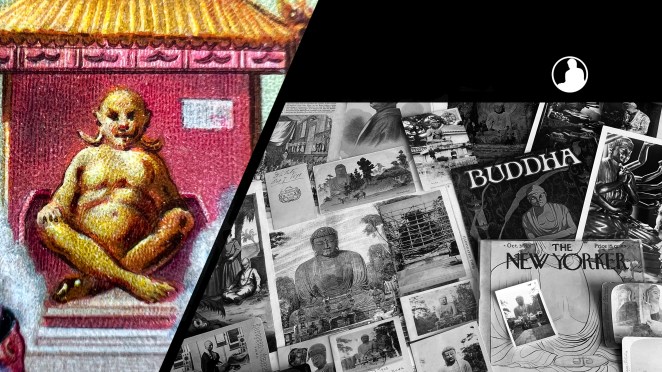

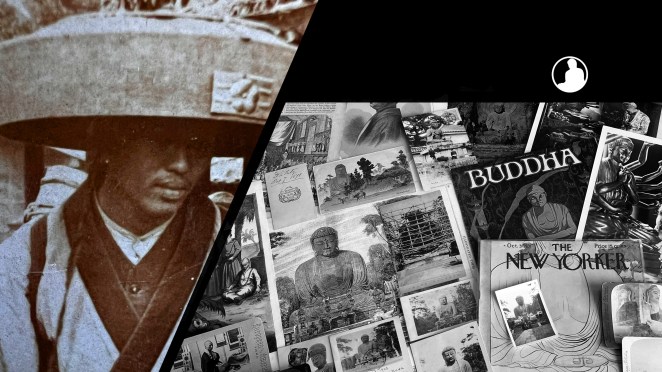

Cambodian “natives” were also brought in to add authenticity to the fabricated environment. The golden-clad Cambodian royal dance troupe proved to be a “must see” attraction; curiously, they performed the Orientalist opera Lakmé by composer Léo Delibes.

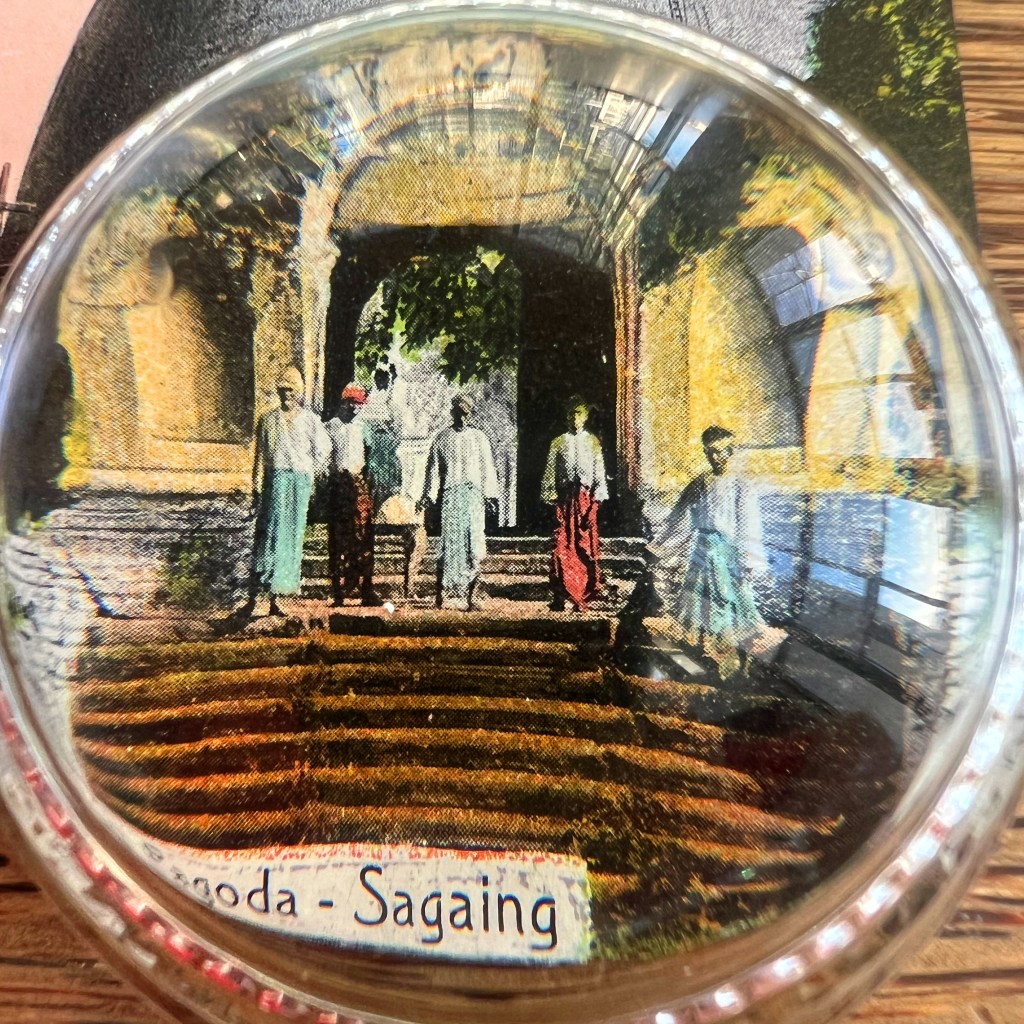

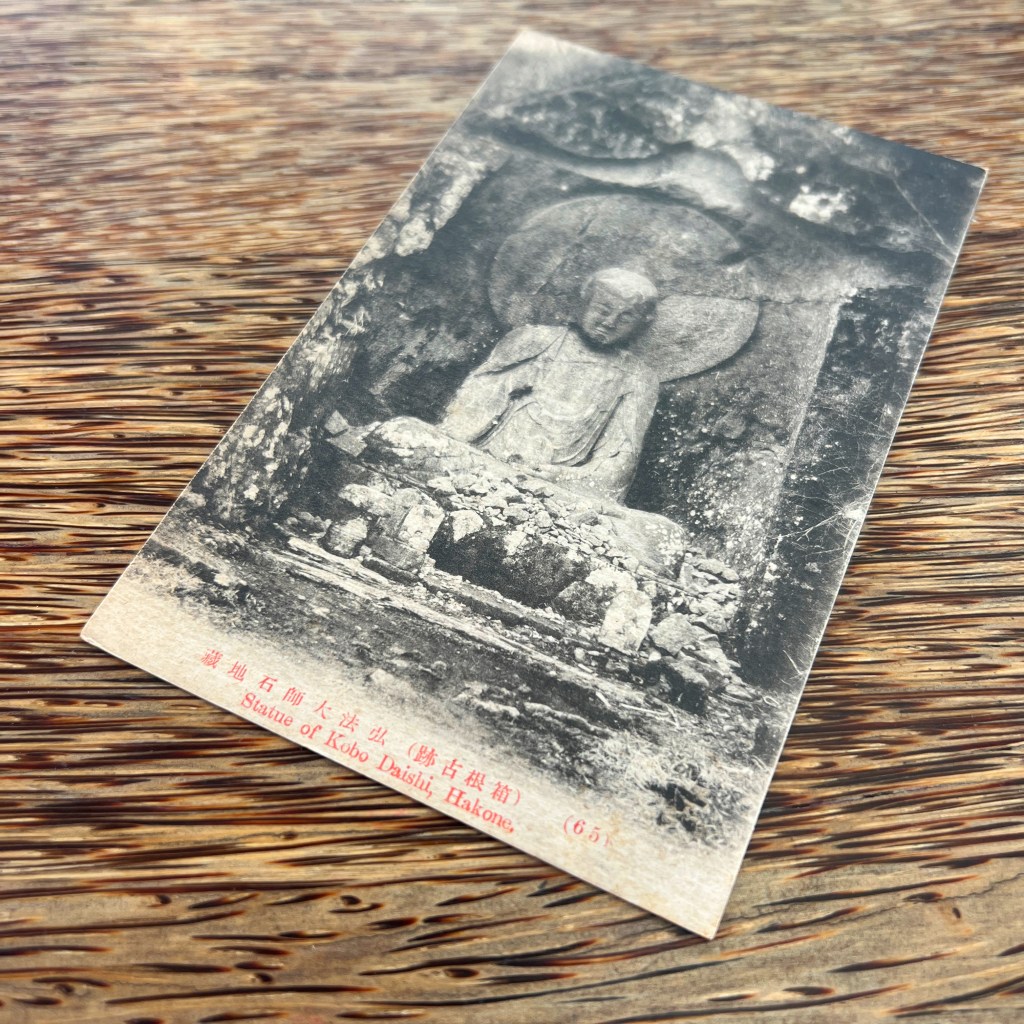

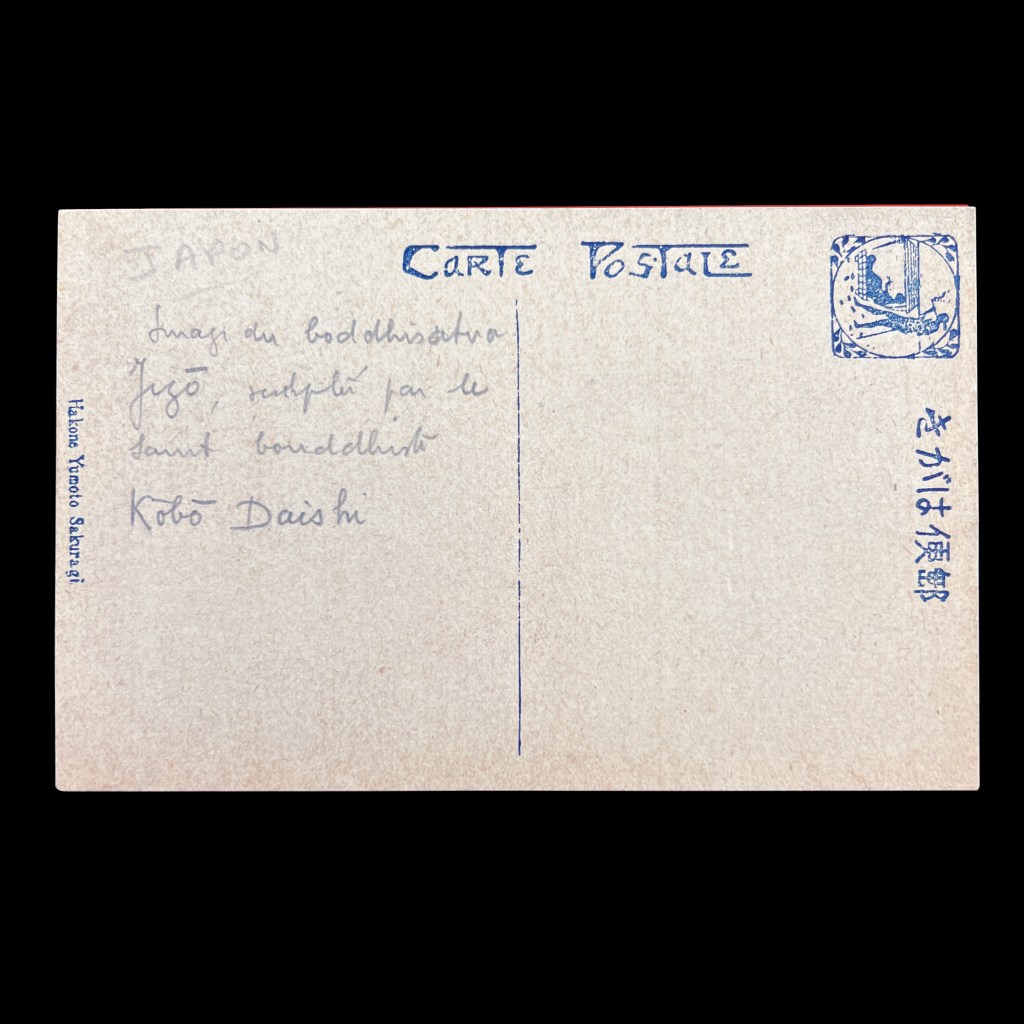

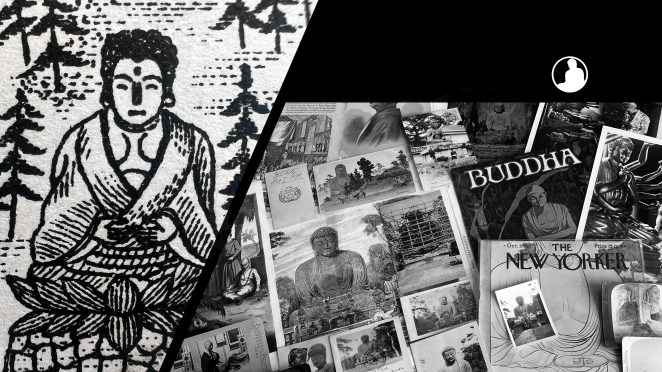

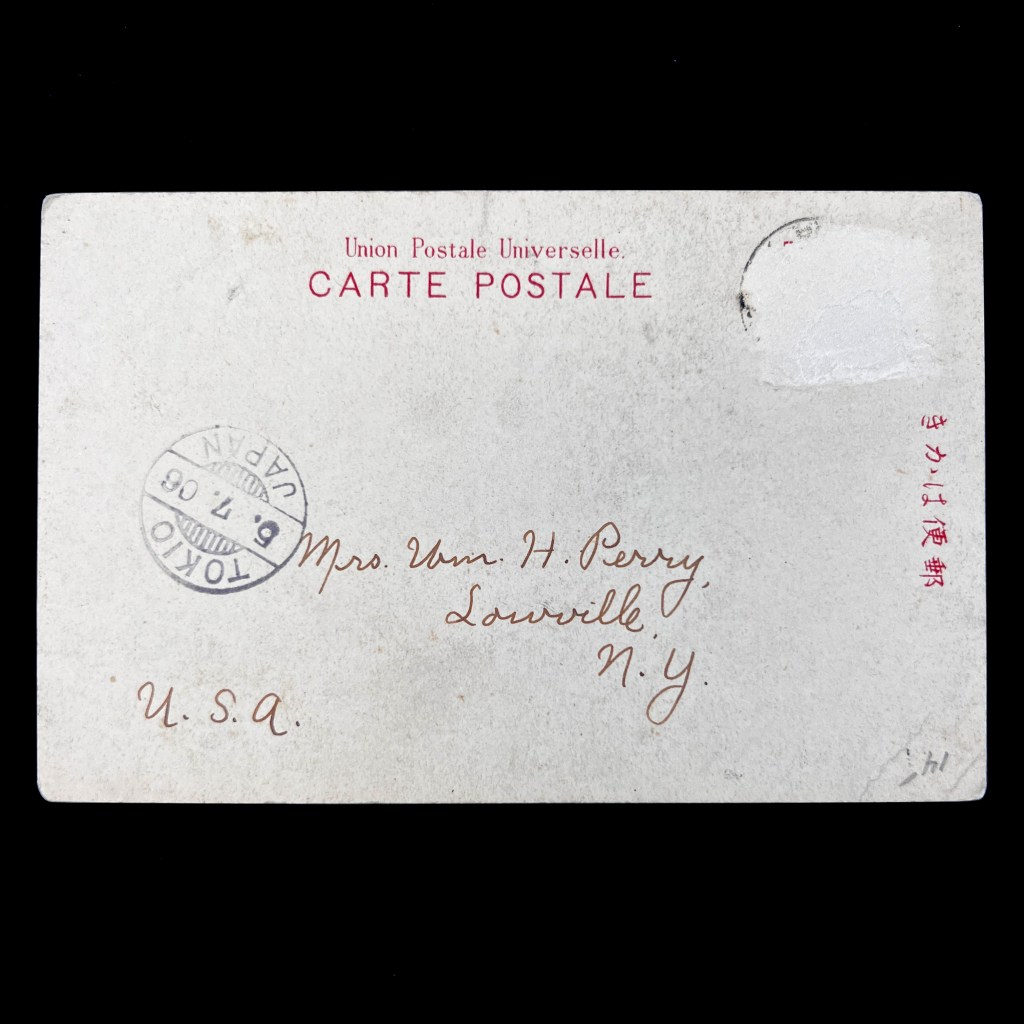

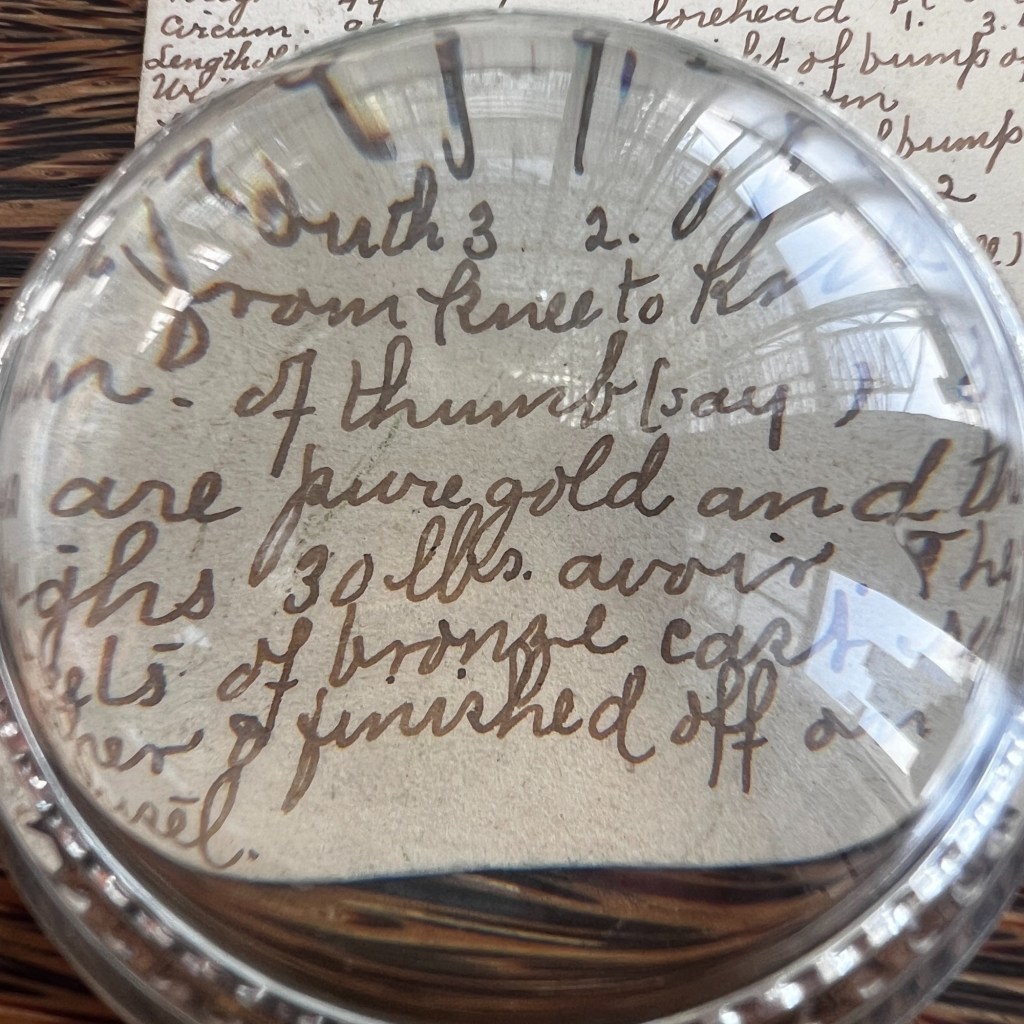

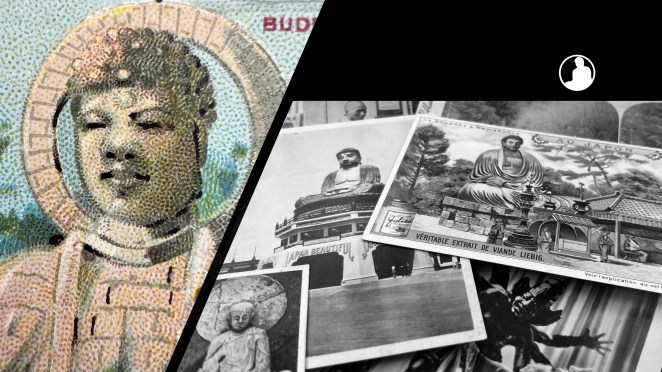

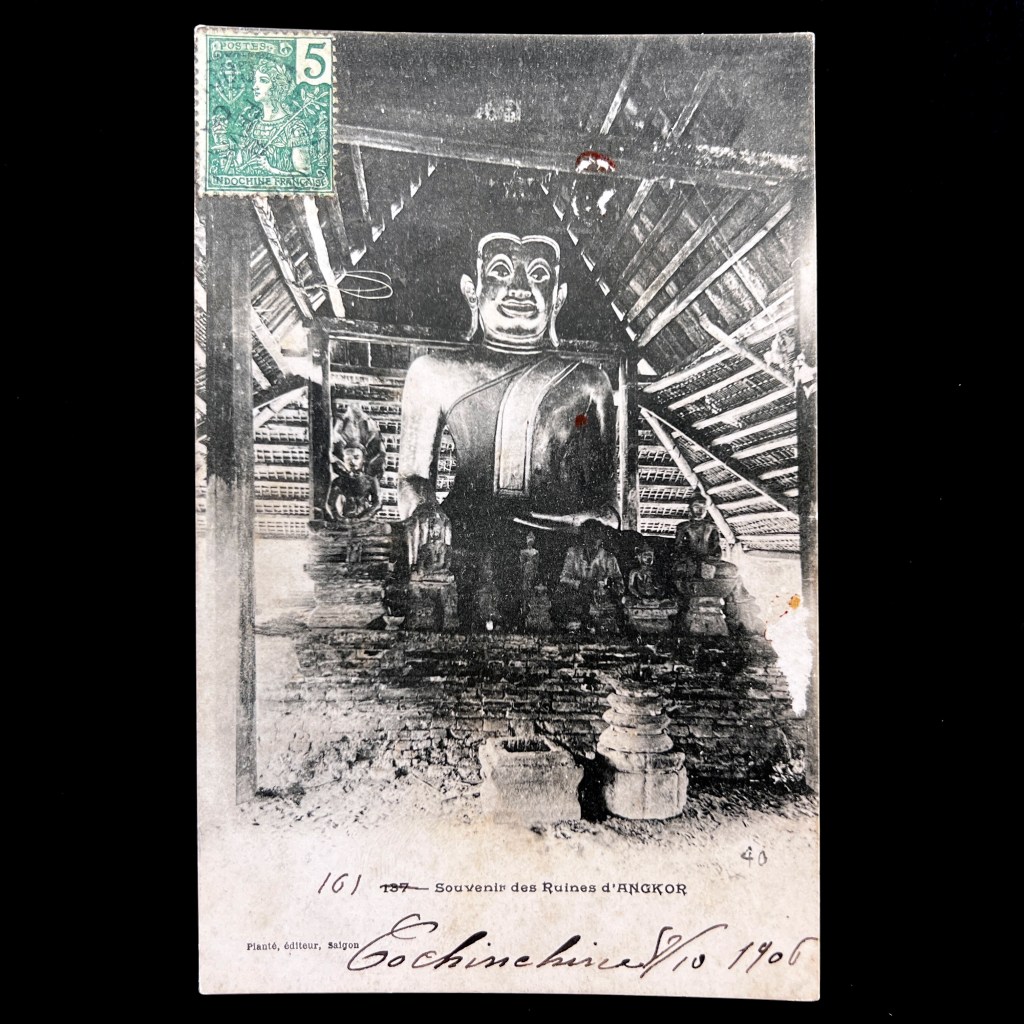

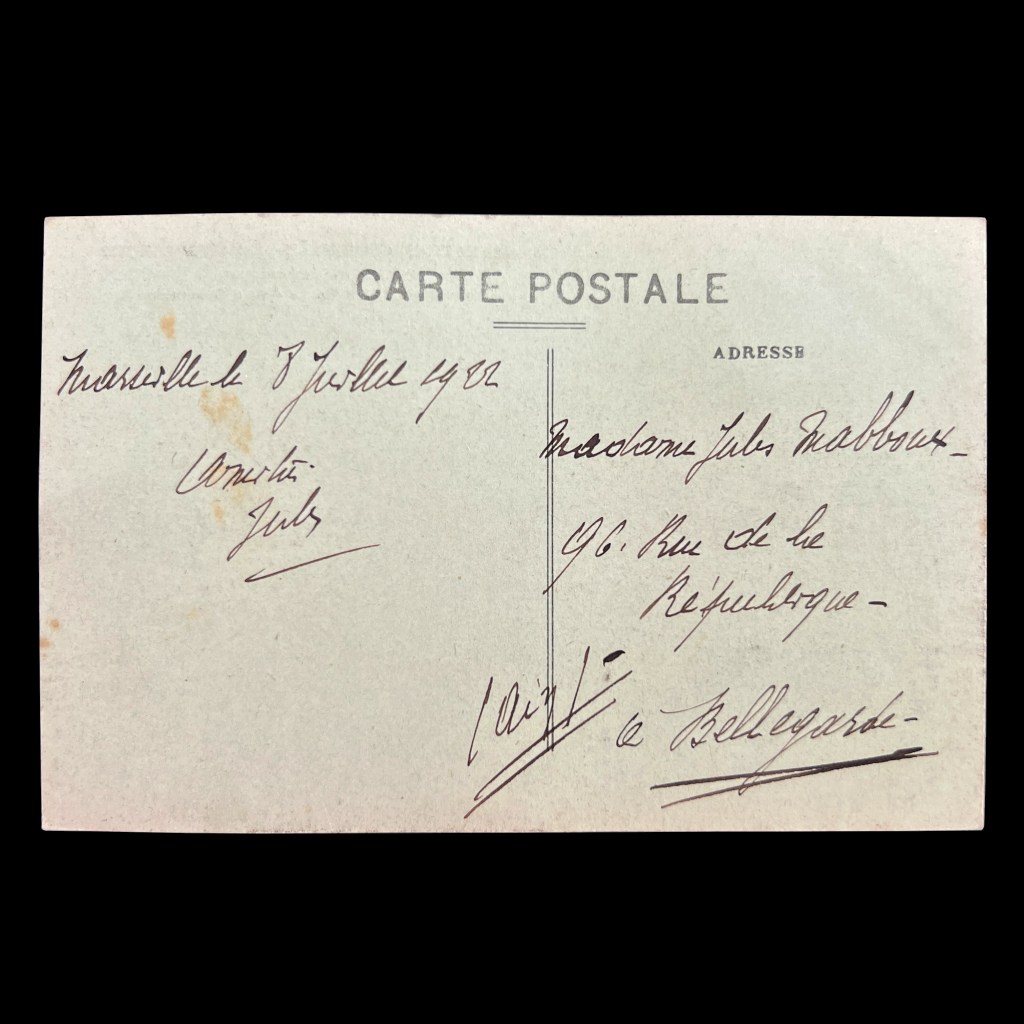

Cambodia was a protectorate of France since 1863 and French troops had already been sending home picture postcards of the real Angkor Wat ruins. Dated July 8, 1922, this card depicting Angkor Wat’s replica was prepared, but never mailed.

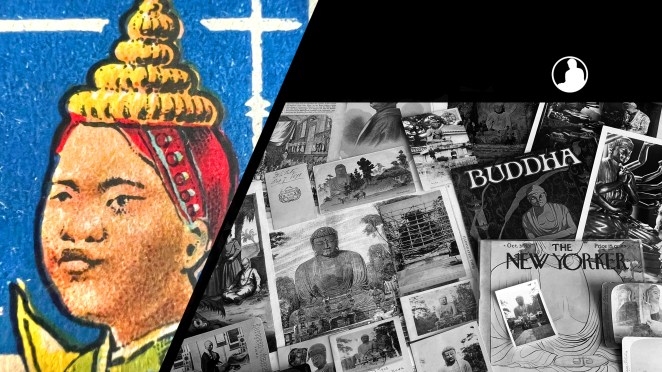

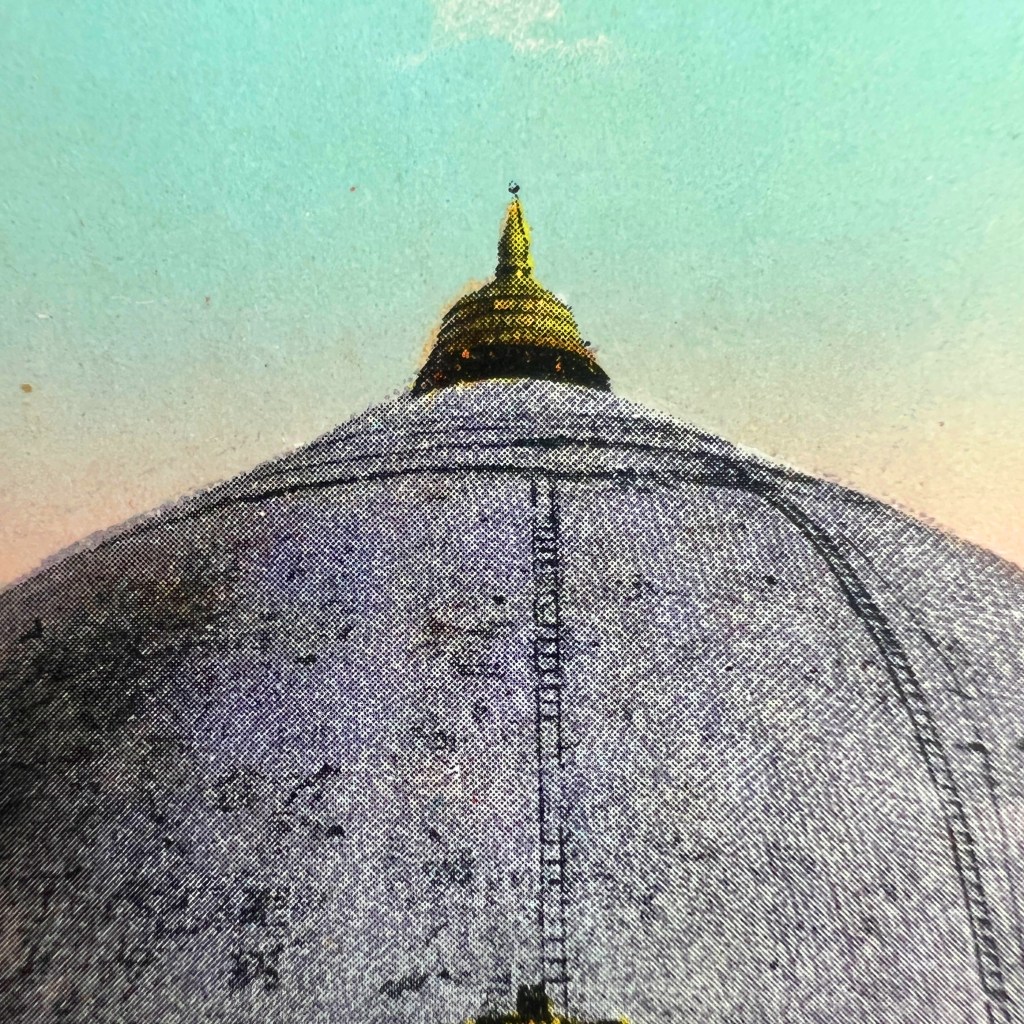

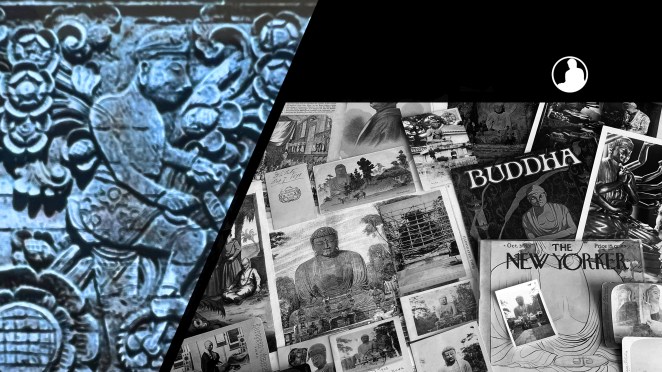

This stamp is a non-postal commemorative stamp, one of twelve designs made for the 1922 Marseille exposition. It depicts a royal dancer wearing a crown shaped like a Southeast Asian Buddhist stupa; such crowns are also seen in the stone reliefs decorating Angkor Wat.

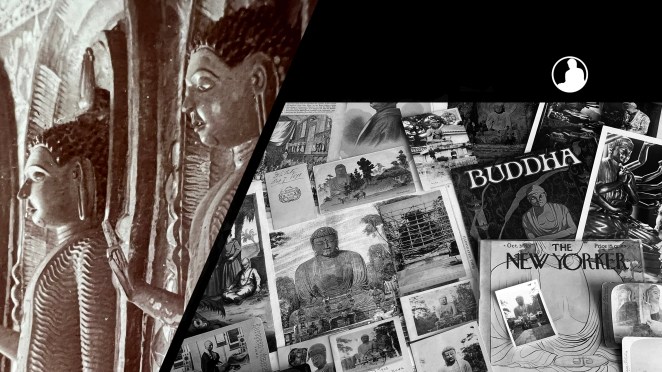

While plasters casts made in Cambodia were used in Marseille, the replica temple had many alterations, creating only a semblance of reality. For more on the use of plasters casts and dancers, see Isabelle Flour’s “Orientalism and the Reality Effect: Angkor at the Universal Expositions” (2014).

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Expositions:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: