For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

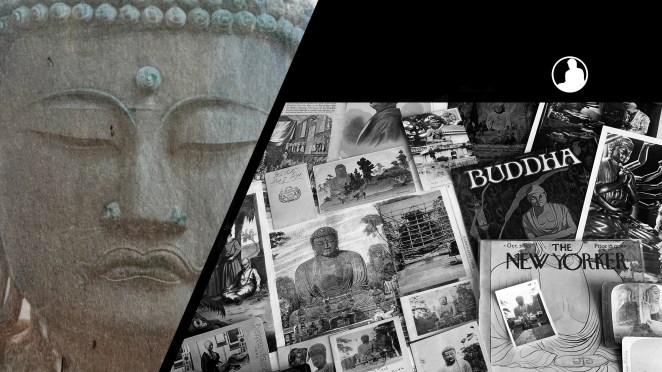

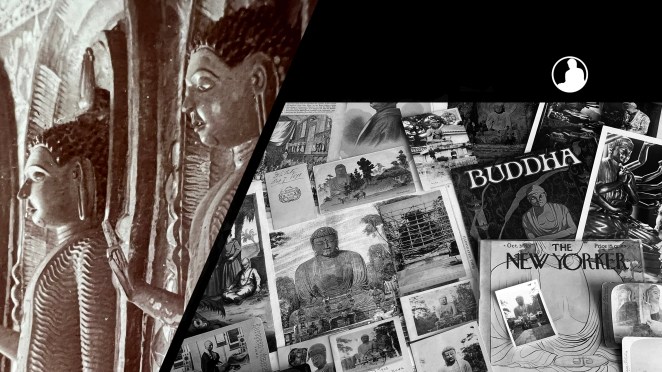

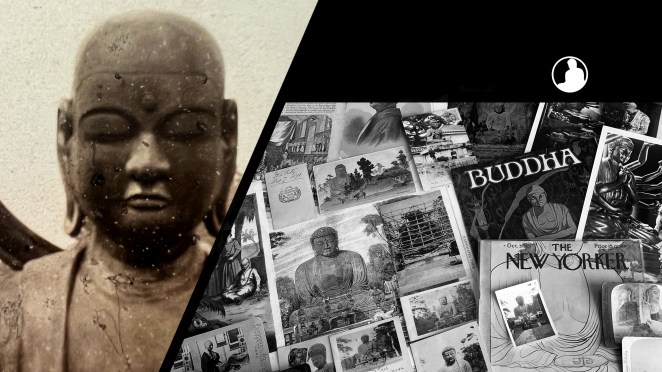

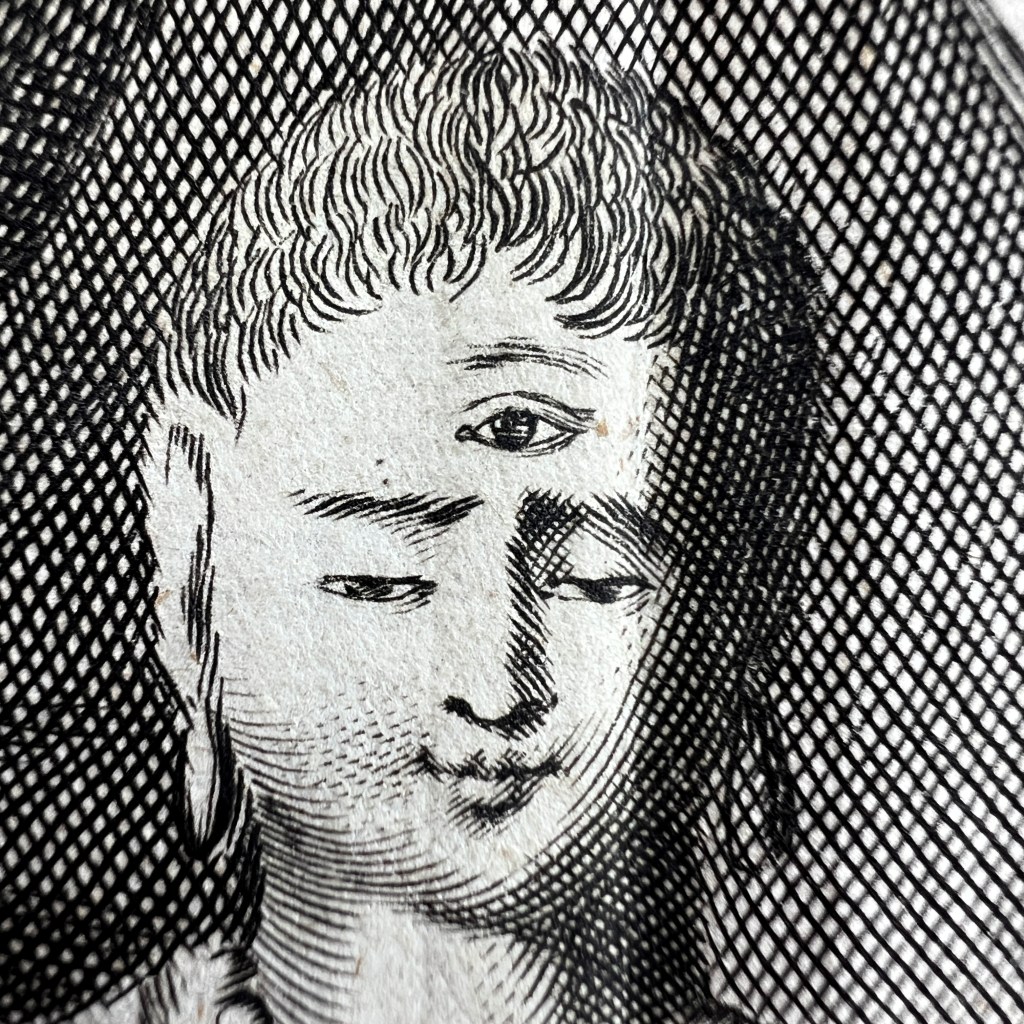

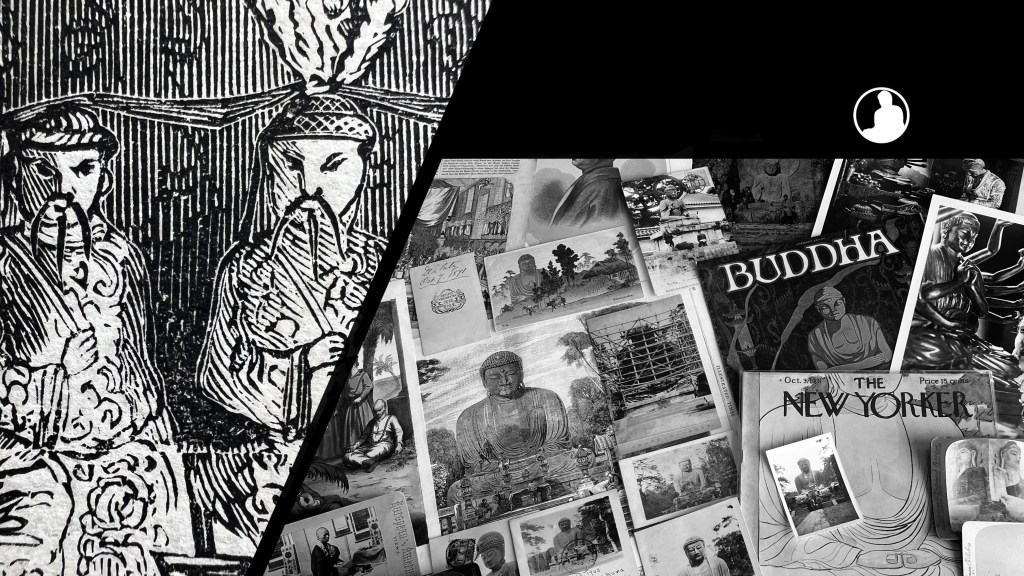

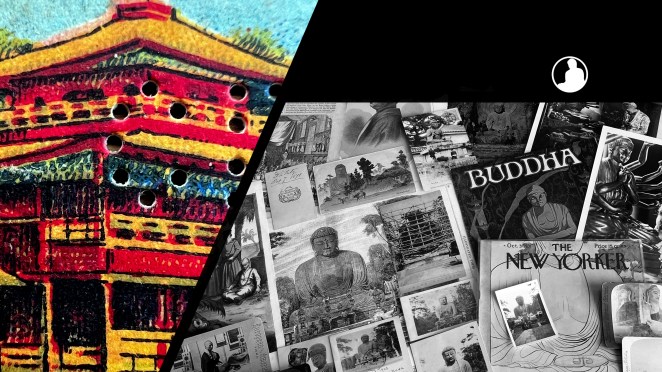

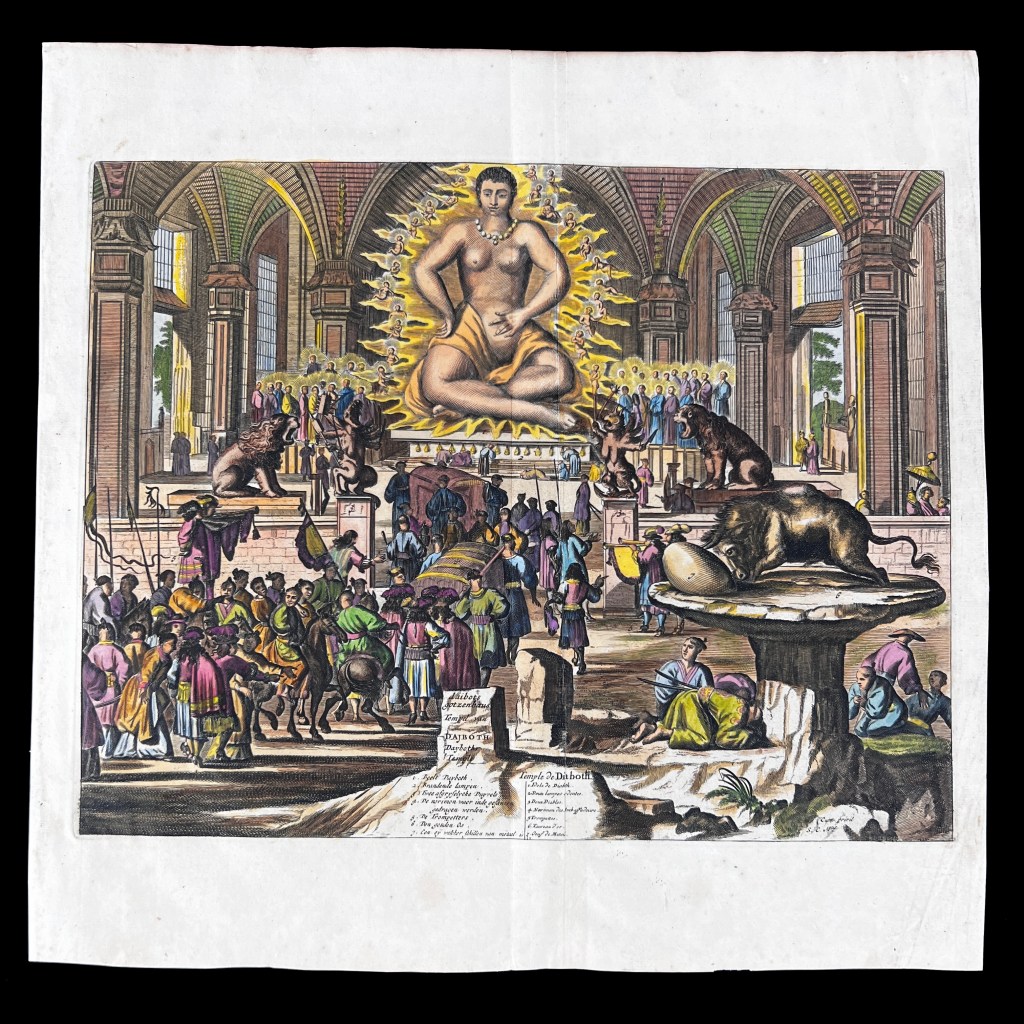

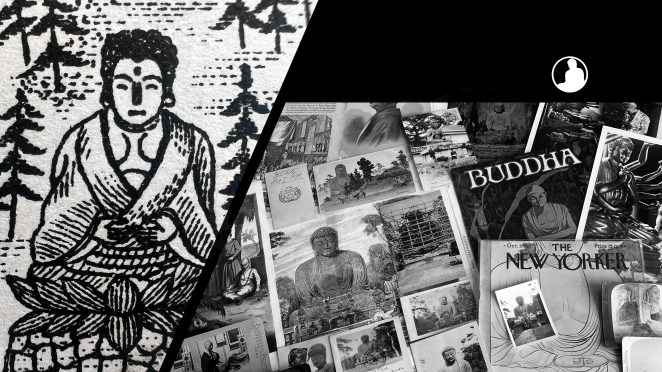

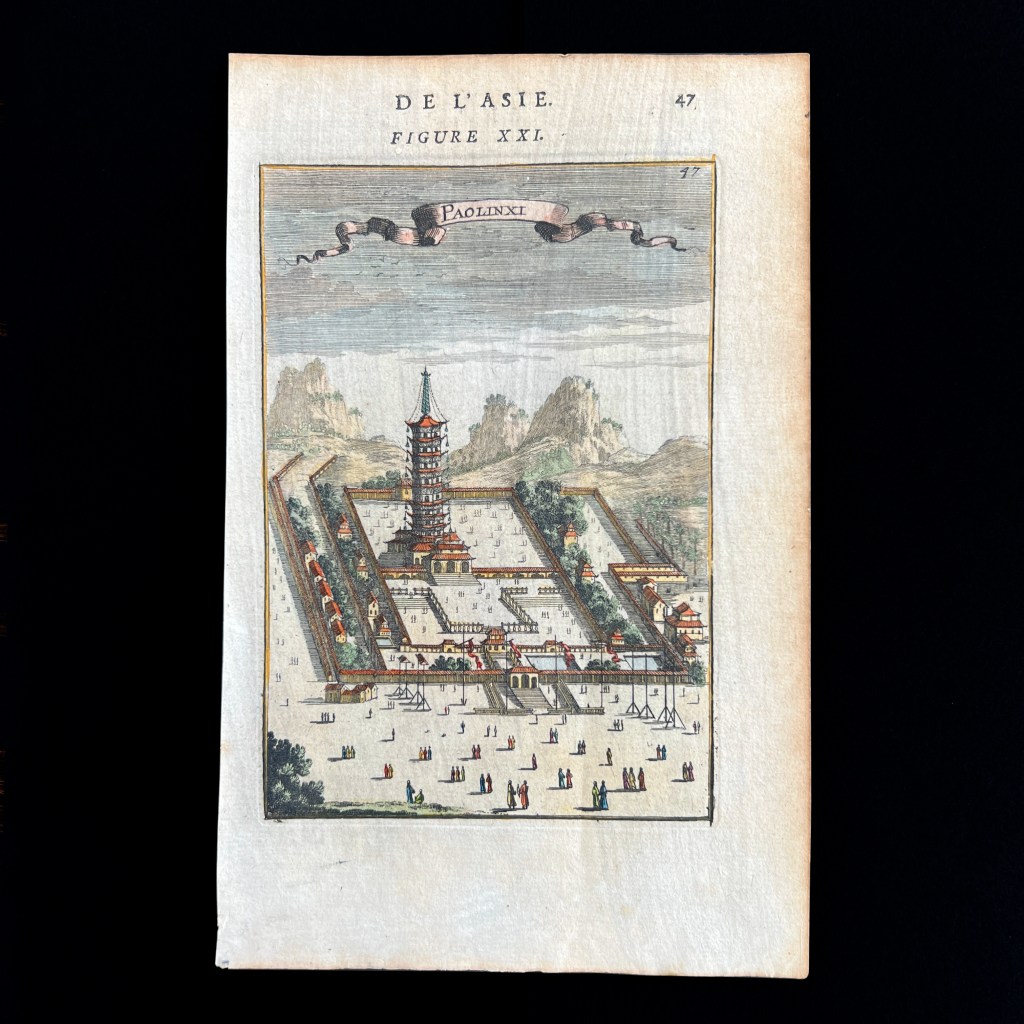

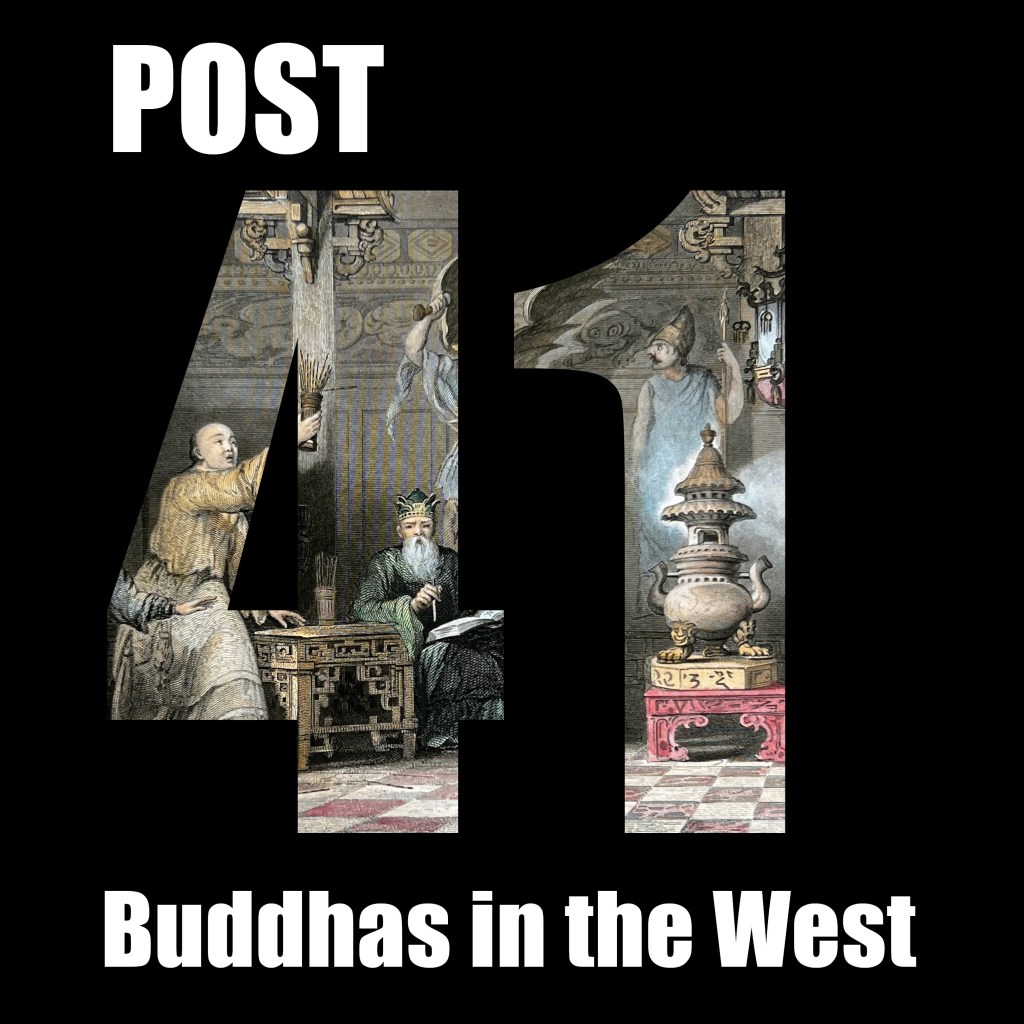

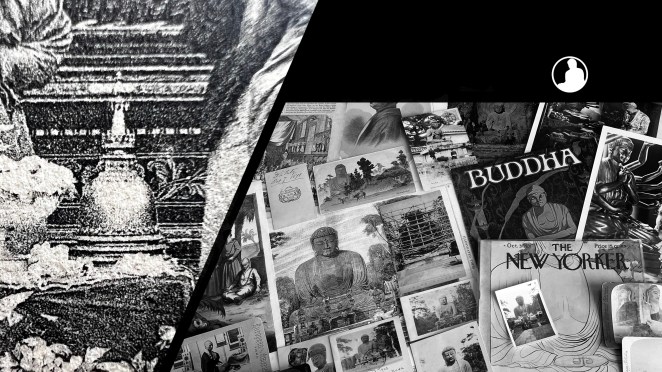

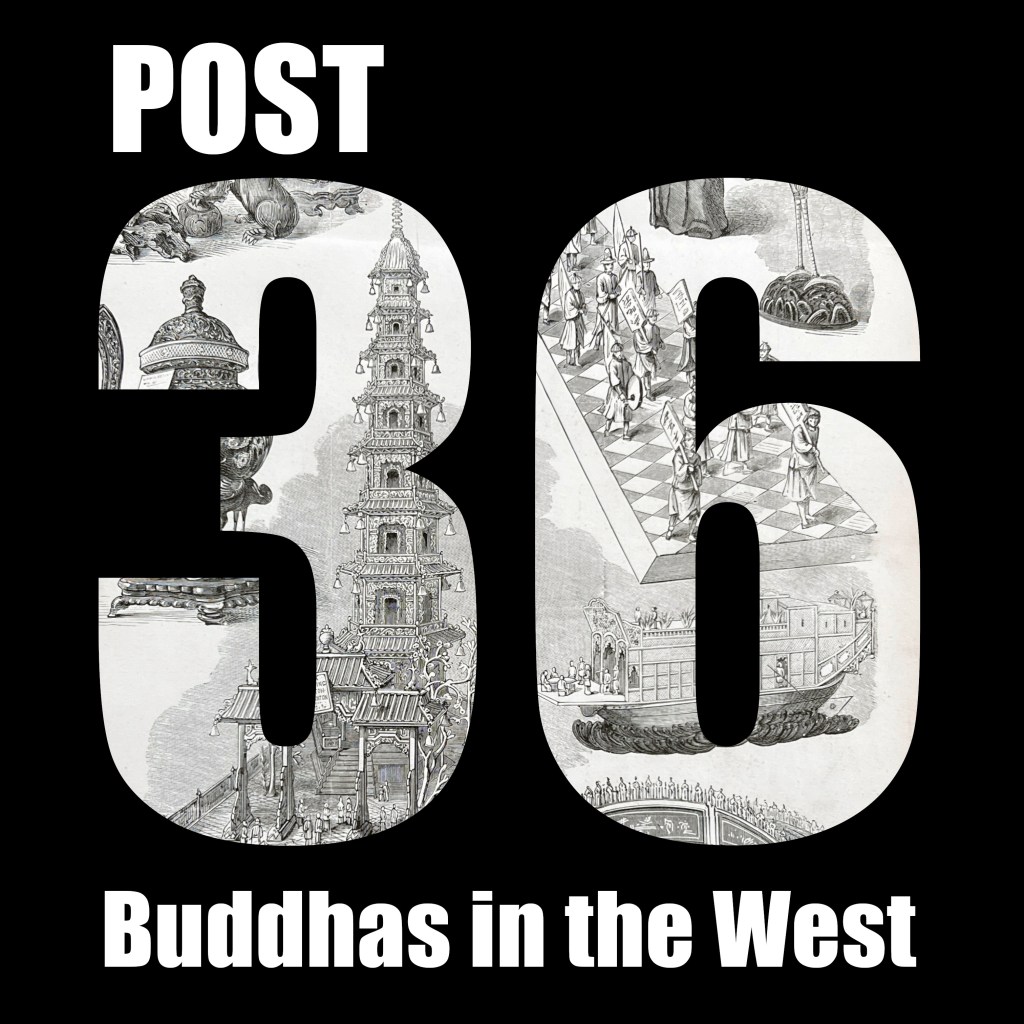

Following a pair of successful illustrated works on China, publisher Jacob van Meurs secured the rights to issue an illustrated book on Japan in 1669. The engravings, such as we see with the curious Buddhist icon here, were criticized for departing “a long way from the truth.”

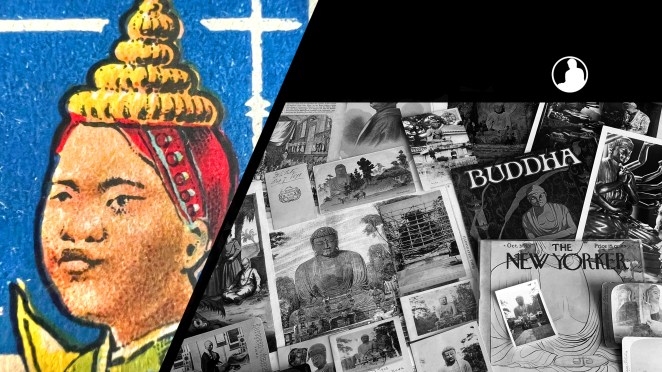

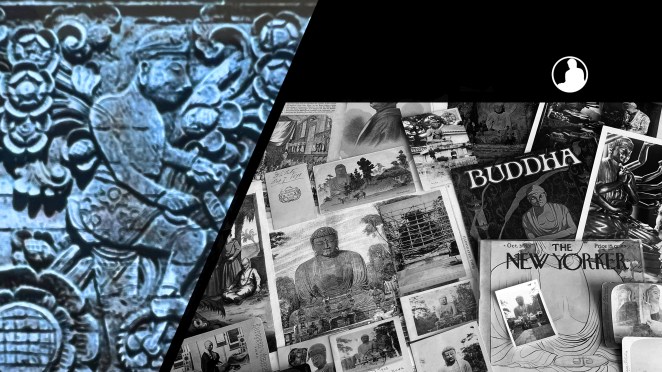

Compiled by Arnoldus Montanus, a Protestant Minister who never left Holland, the engravings in Atlas Japannensis draw from both textual descriptions and an older European visual language of Asian idolatry. The work includes 23 large plates and 71 smaller vignettes set within the text.

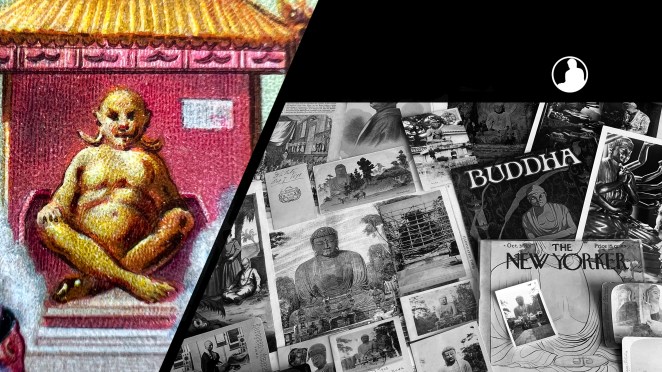

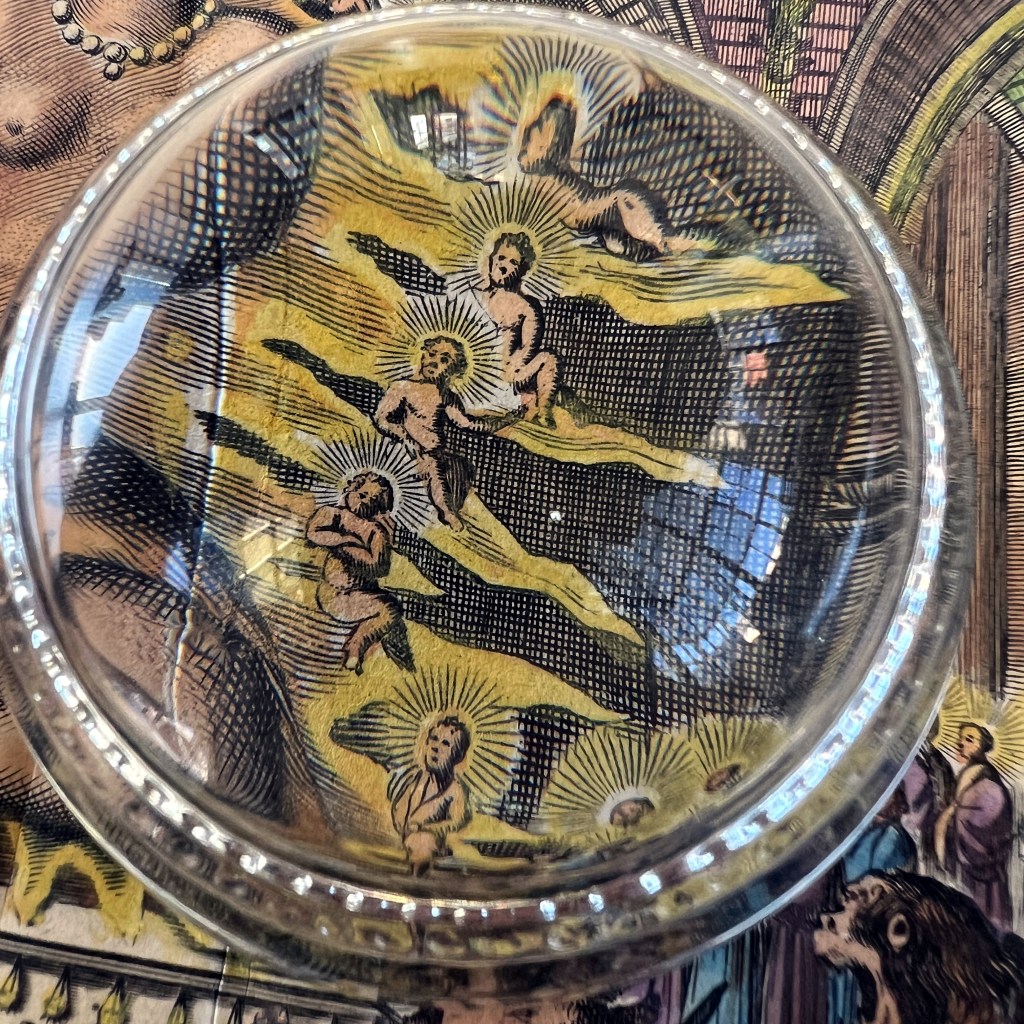

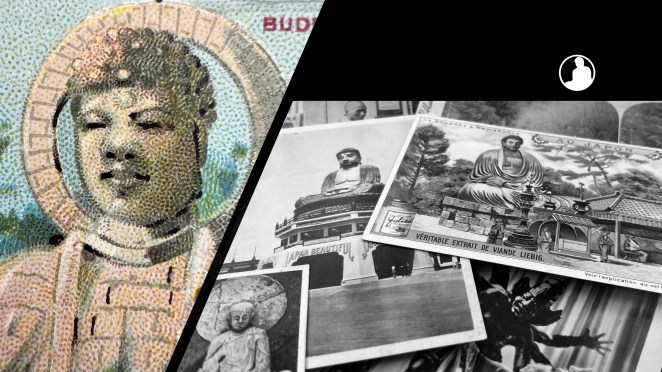

As for the icon here, the English translation of 1670 reads, “This Image hath thirty Arms, and as many Hands, in each two Arrows, a Face representing a handsome Youth, on his Breast seven humane Faces, with a Crown of Gold, richly inchas’d with Peals, Diamonds, and all sorts of Precious Gems.”

While multi-armed and multi-headed figures are not uncommon in Buddhism, the particular configuration here appears rather fanciful. Nevertheless, we are informed the illustration here represents the Bodhisattva Kannon, further curiously identified in the text as the son of Amida Buddha.

The markings on the pedestal are meant to signify non-alphabetic East Asian writing, but none can be resolved into legible characters.

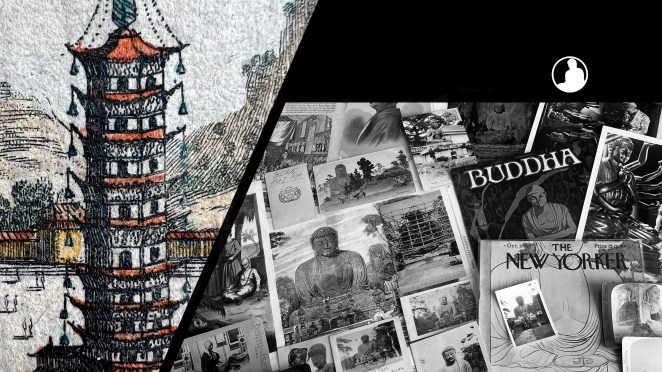

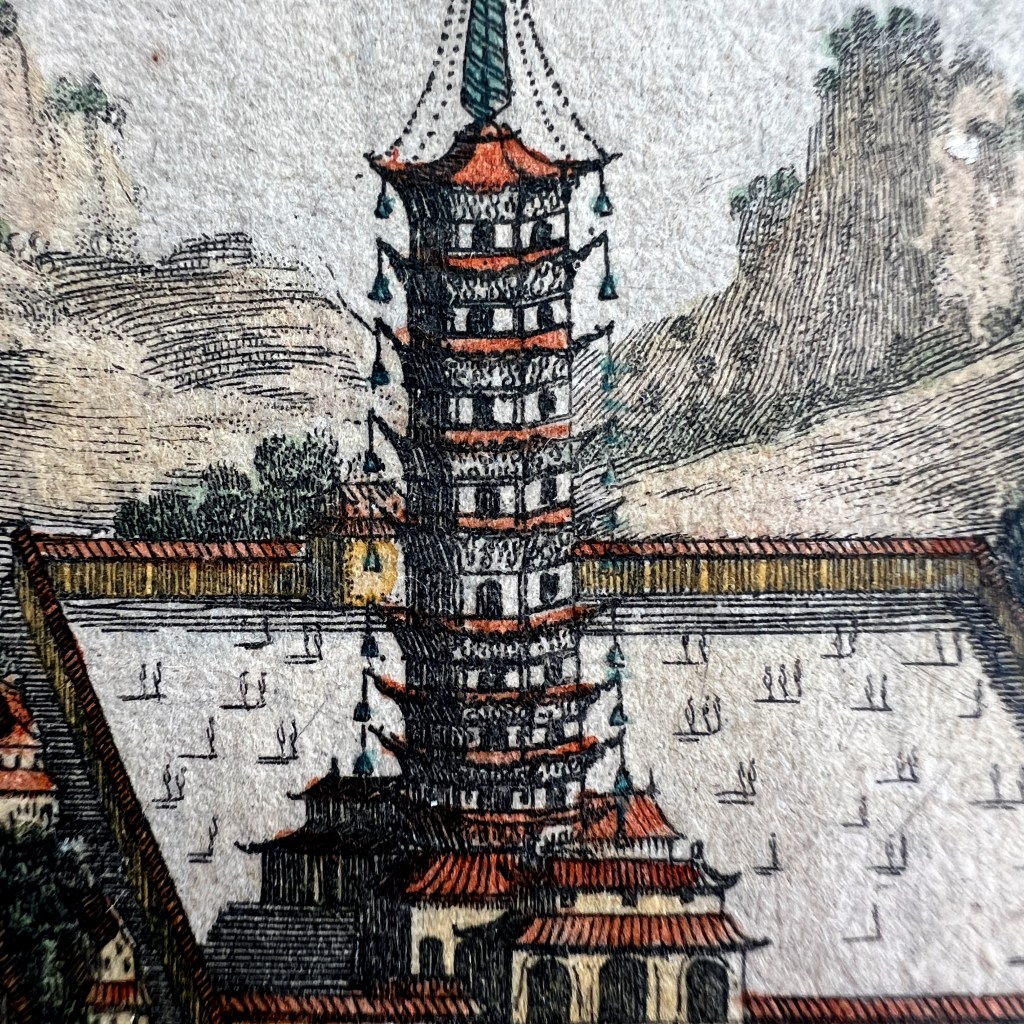

Kannon’s temple is said to be located on a Buddhist mountain just east of Kyoto, most likely pointing to Mt. Hiei. The fires indicate part of Mt. Hiei’s history, as described by Montanus, when Oda Nobunaga razed Buddhist temples in the region in 1571.

Several of Montanus’ engravings were copied into later works on Japan, helping shape a visual lexicon for Buddhism into the 19th cent. The 1669 Dutch edition of Atlas Japannensis has been digitized by the National Library of the Netherlands, viewable here: tinyurl.com/5n6kstfy.

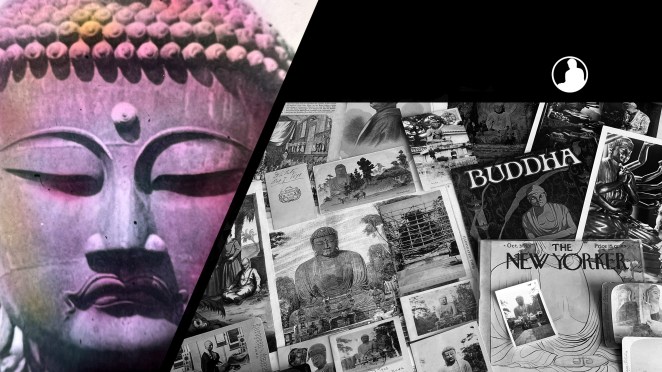

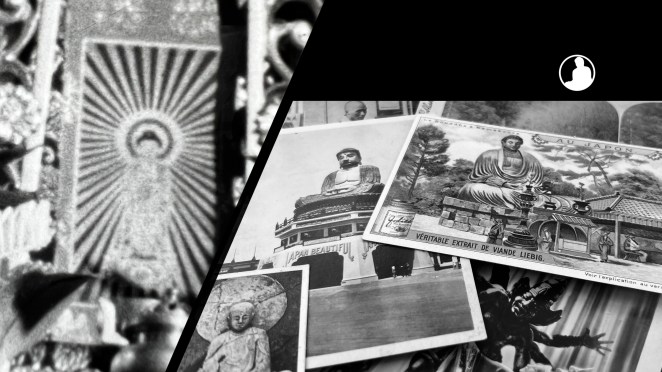

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring Historical Engravings:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: