For all the new Buddhas in the West posts

follow us on Bluesky & Instagram

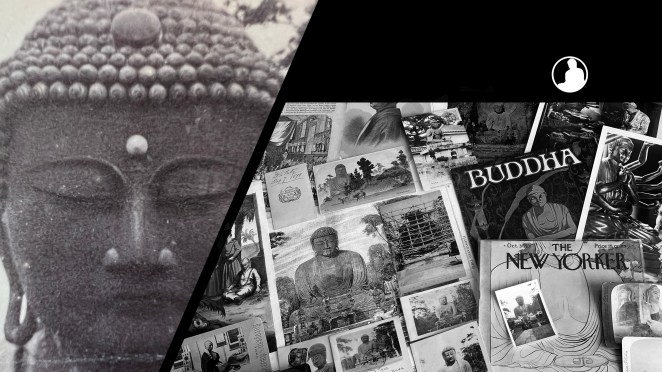

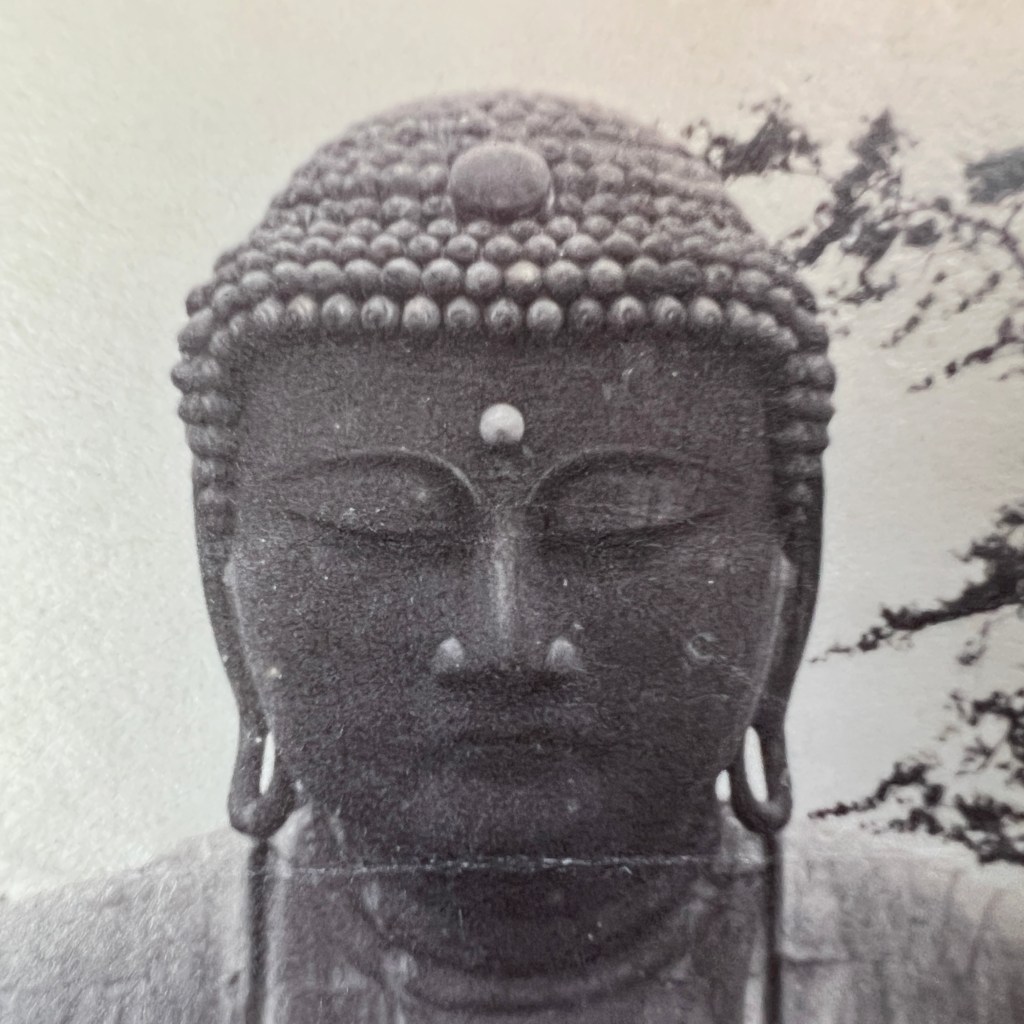

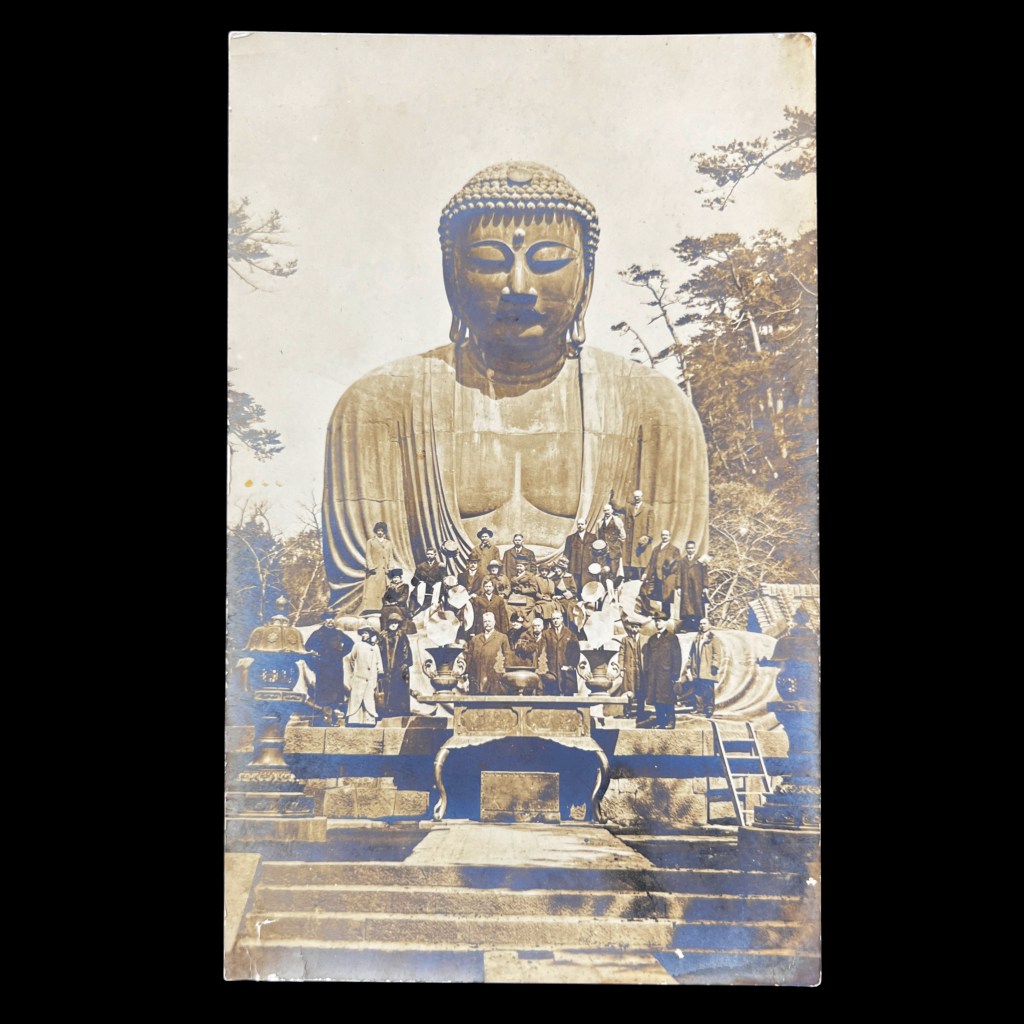

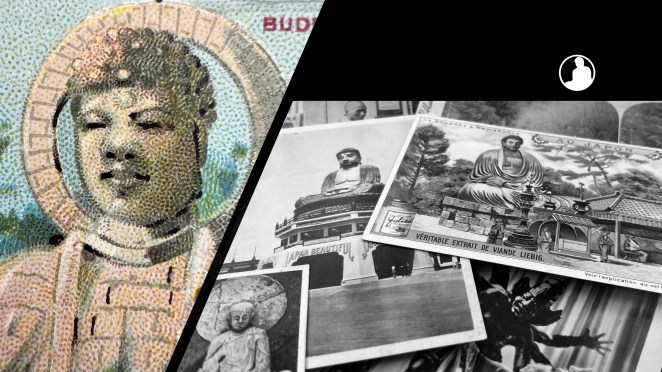

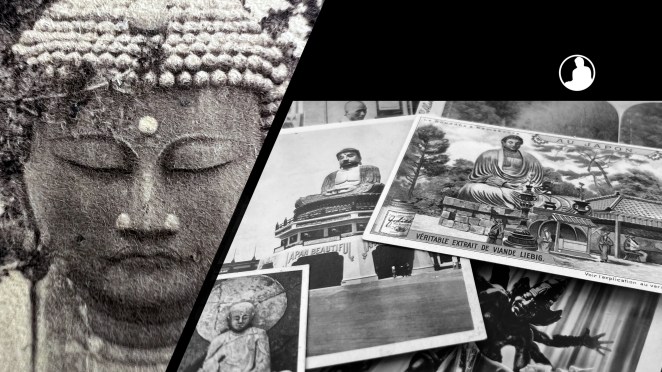

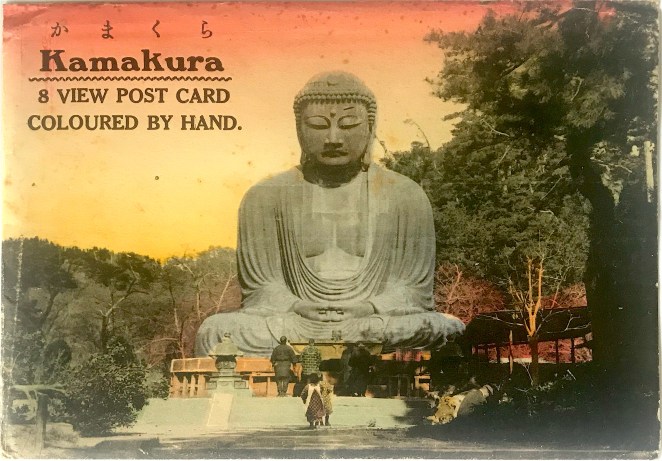

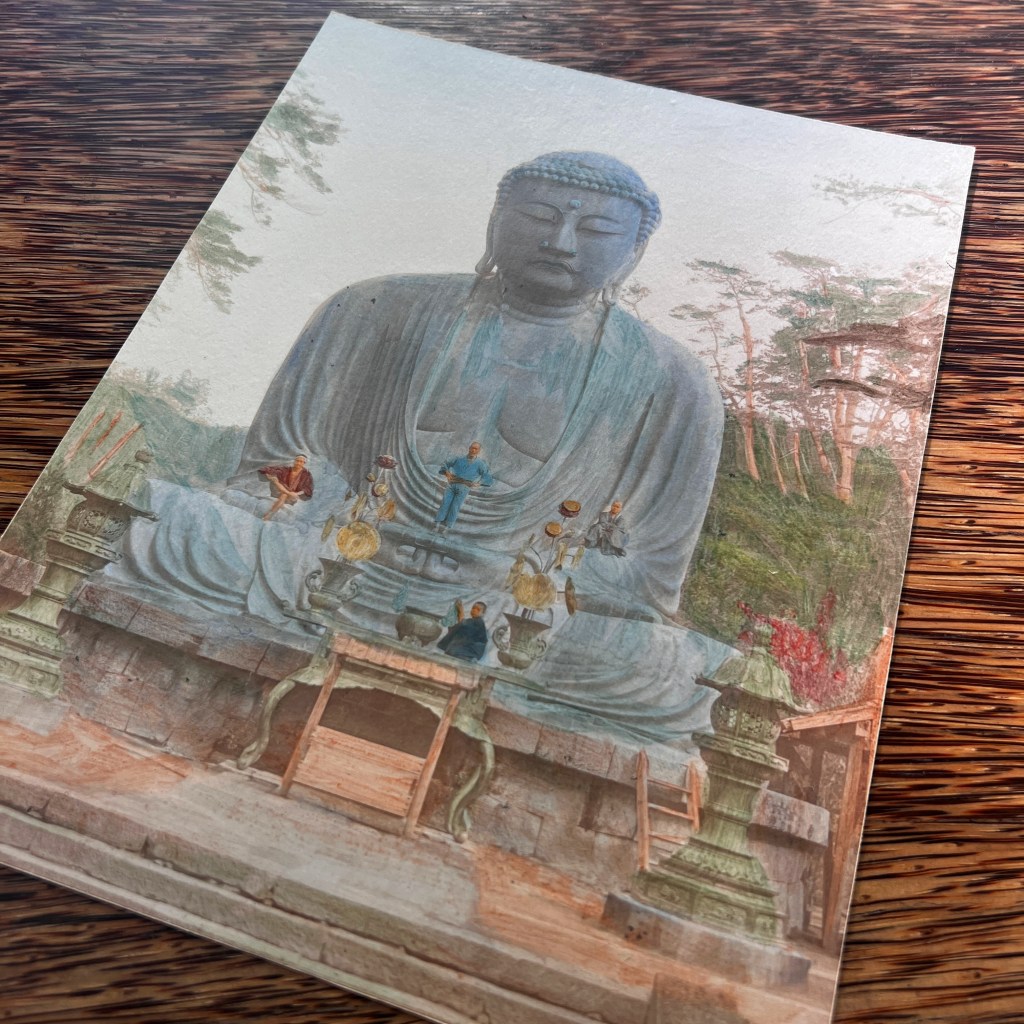

An astounding 400,000 hand-colored photographic prints were used for all editions of Francis Brinkley’s Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese. Produced in Boston between 1897 and 1898, this work was the pinnacle of photographic book publishing at the turn of the century.

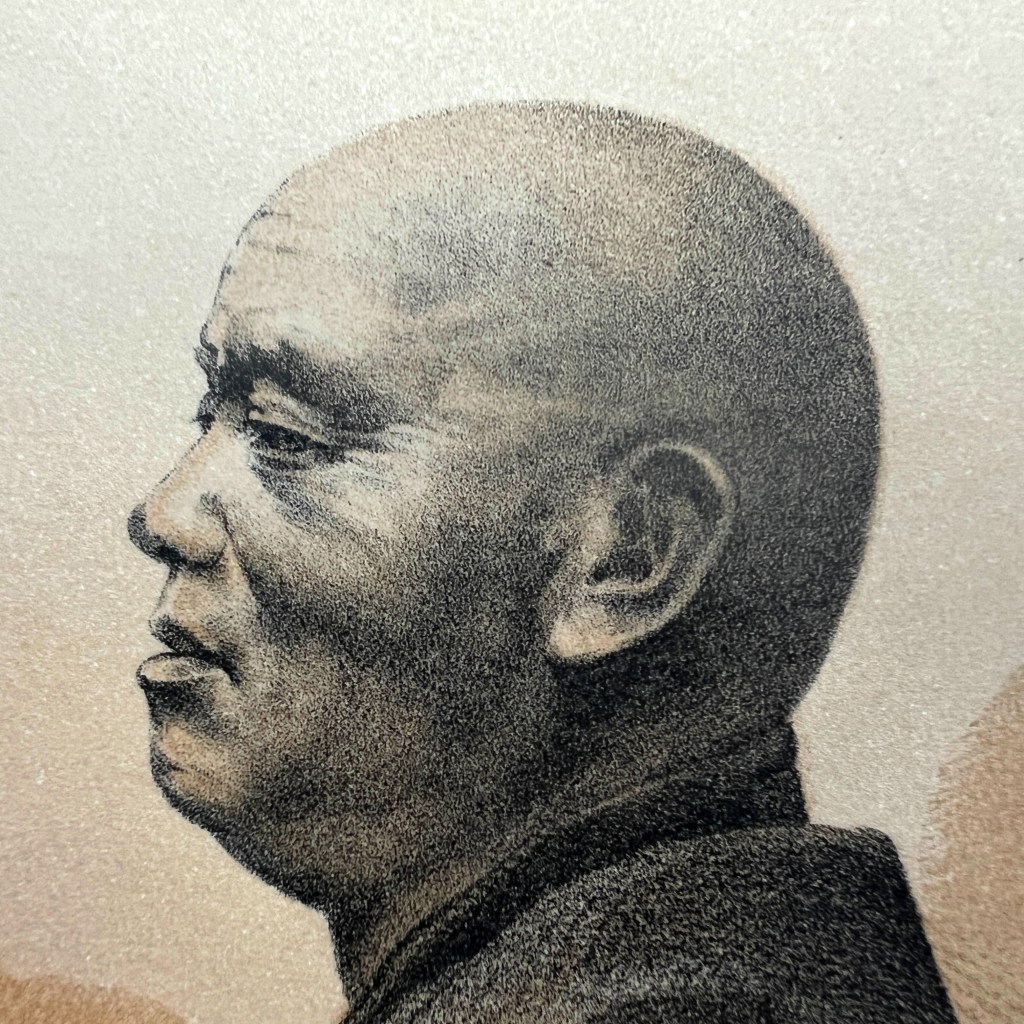

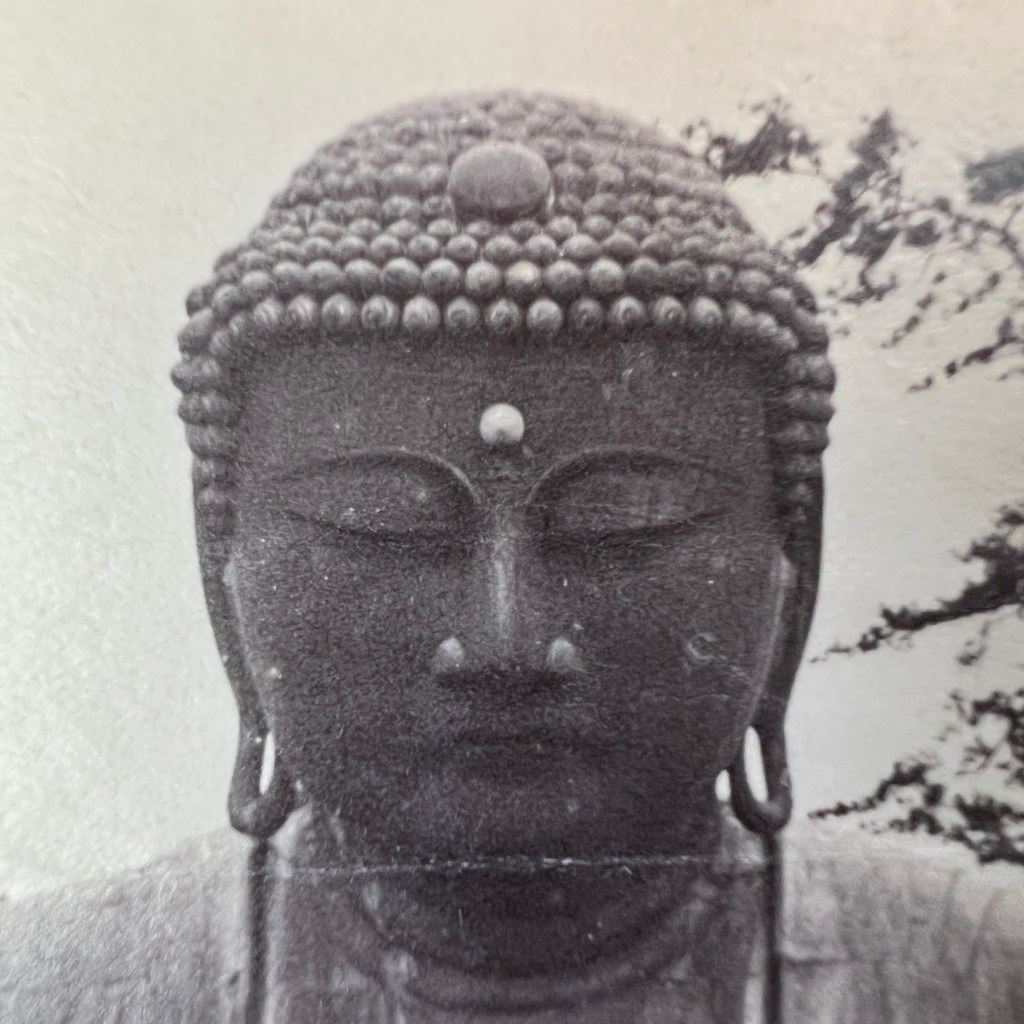

The photographs were imported from Japan from the Yokohama studio of Tamamura Kōzaburō, one of the most prolific Japanese photographers of his generation. He reportedly employed 350 artists for several months to complete the job, yet Tamamura’s name is omitted from the final publication.

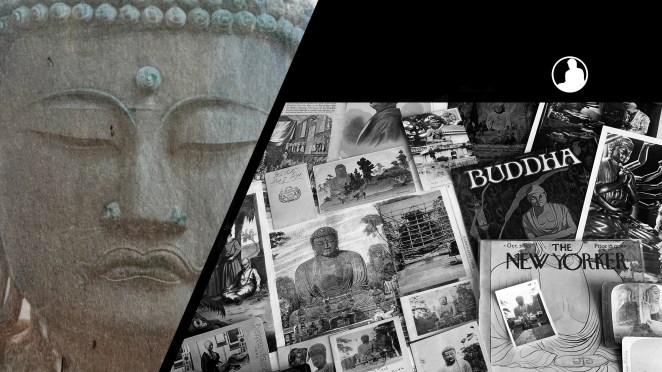

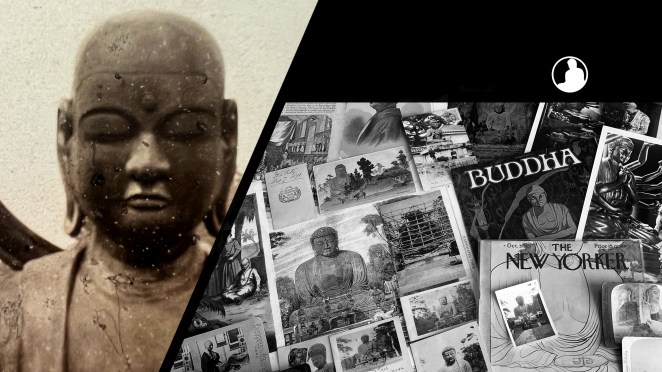

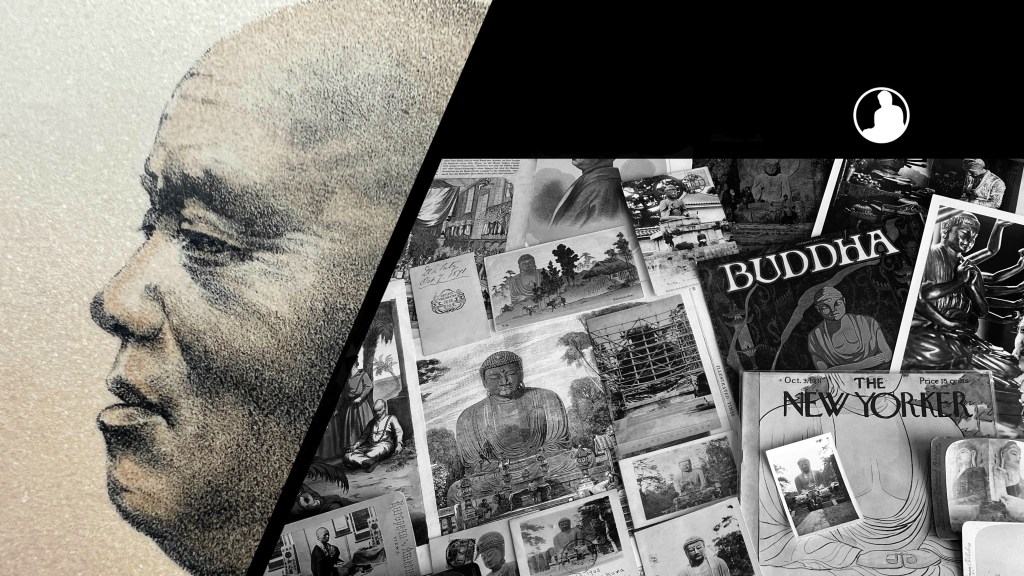

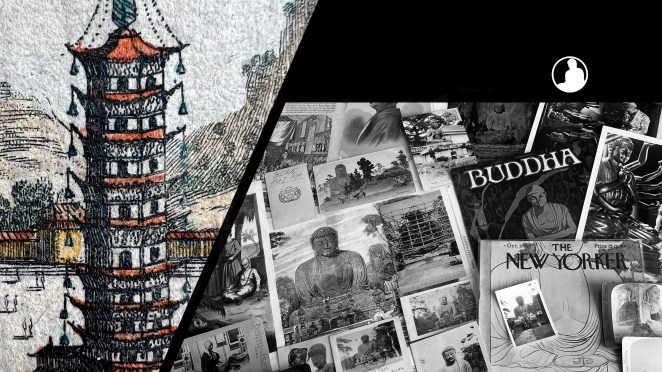

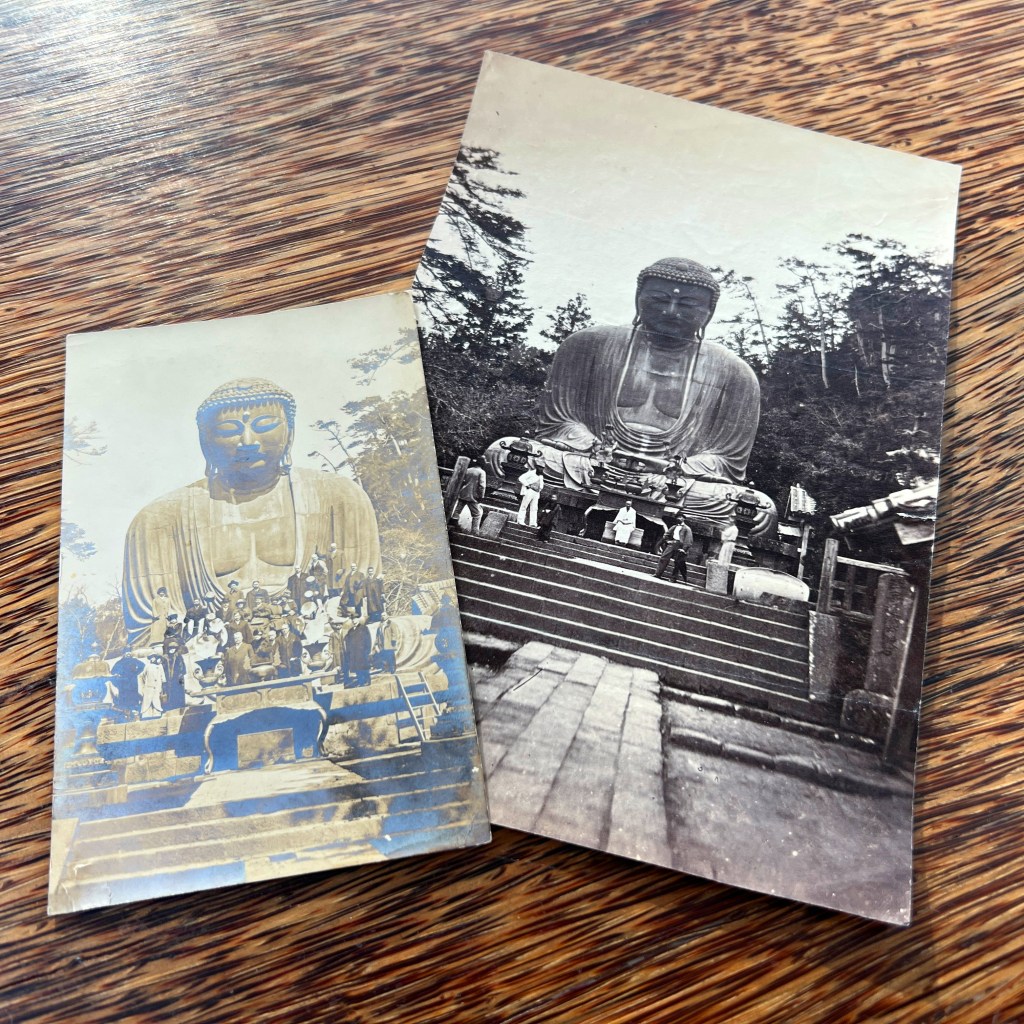

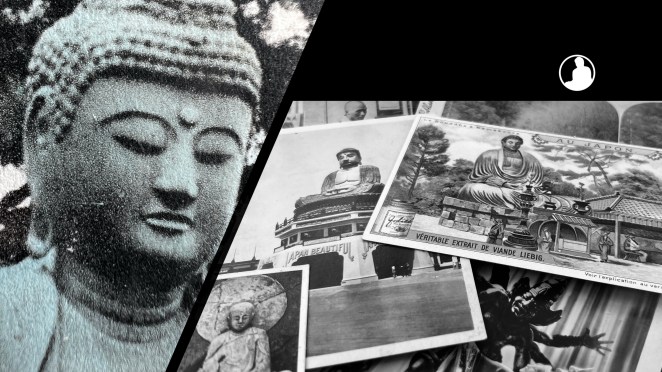

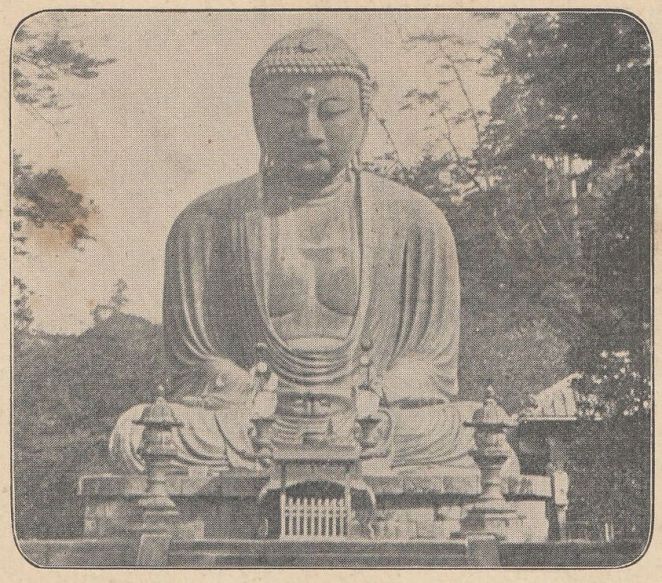

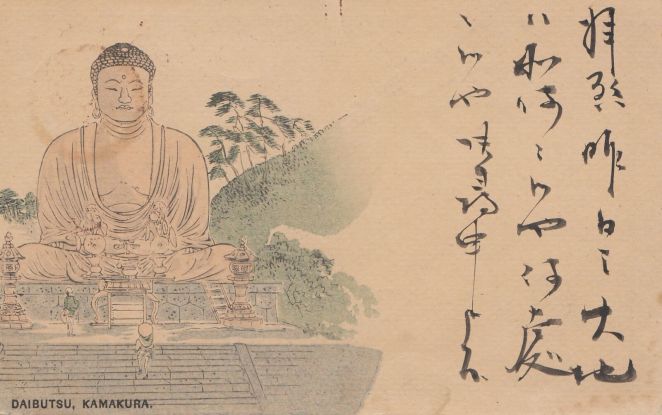

Unlike most books of the era which used photomechanical prints, Brinkley’s Japan used mounted photographs. The Great Buddha of Kamakura was the second full page photograph, following Mt. Fuji, in the first volume, suggesting its perceived value in the American visual language of Japan.

Tamamura’s output was so extensive in preparation for Brinkley’s book, there was a fivefold increase in Japan’s photography exports between 1895 and 1896. This volume of work was achieved at expense of quality, as many of the color washes are pale and poorly executed.

While the number of one million photos for Brinkley’s Japan was likely exaggerated by Tamamura for publicity, this was truly an enormous undertaking. To view the first volume of Brinkley’s Japan held by the Getty Museum, see here: https://tinyurl.com/bddt5z32.

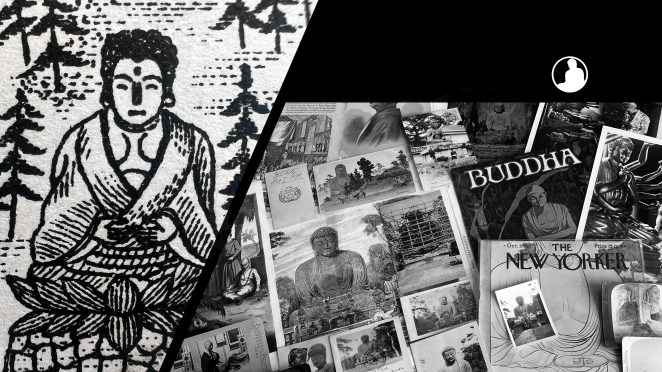

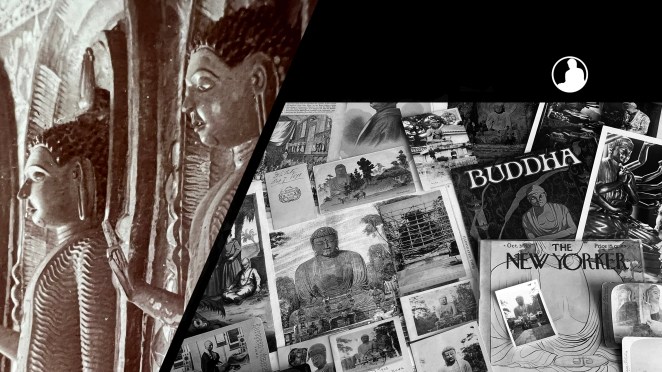

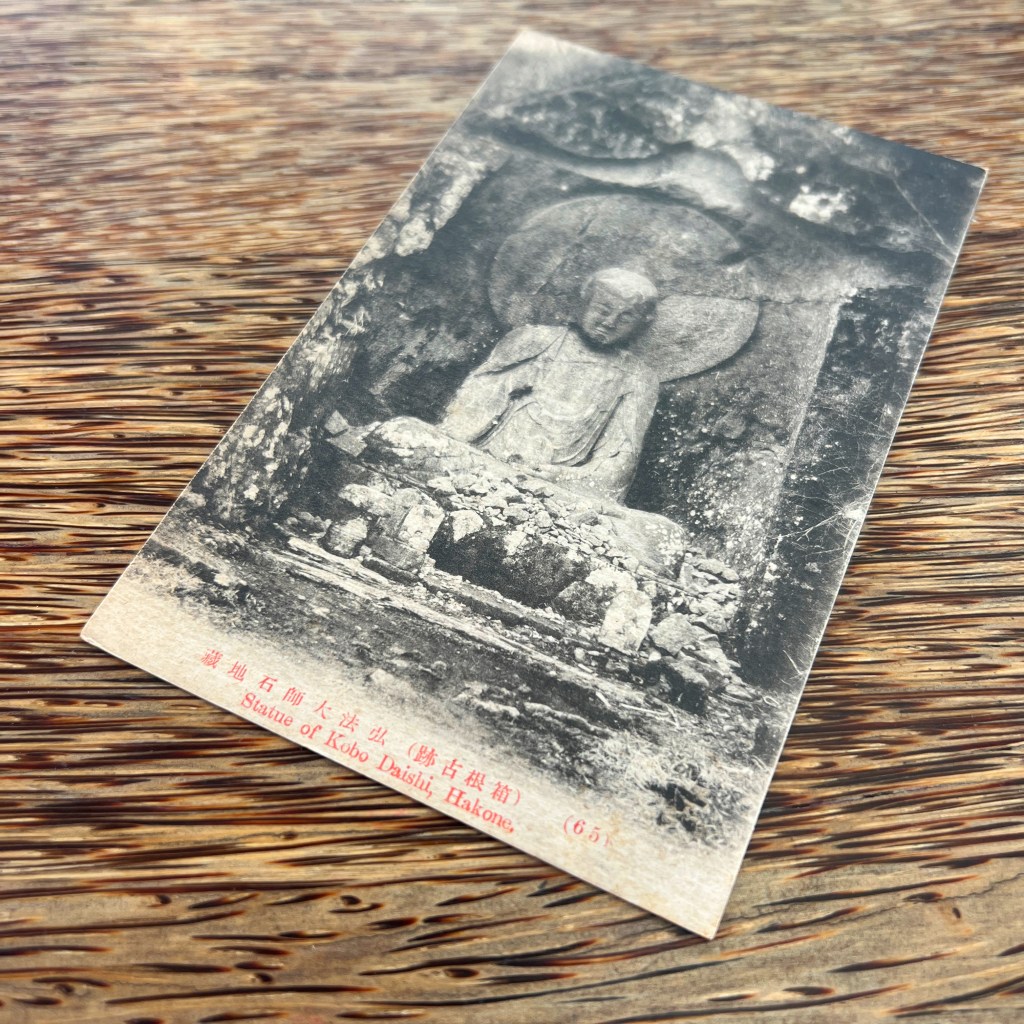

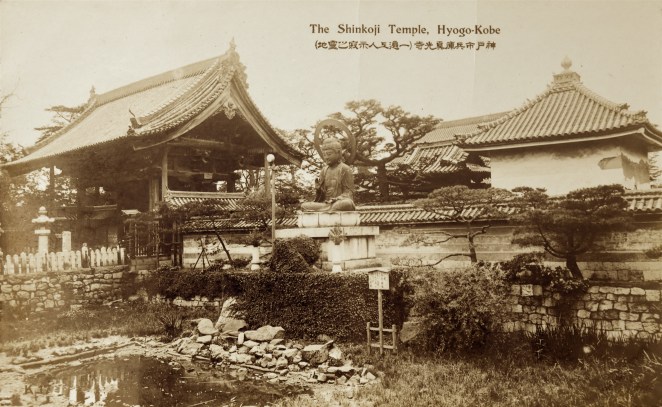

The Buddhas in the West Material Archive is a digital scholarship project that catalogues artifacts depicting Buddhist material culture for Western audiences. It’s comprised of prints, photos, and an assortment of ephemera and other objects. For a brief introduction to this archive, visit the main Buddhas in the West project page.

For Related Buddhas in the West Posts Featuring the Kamakura Daibutsu:

For the Most Recent Buddhas in the West Posts: