Peter Romaskieiwcz

Dedicated to Philip Choy (1926-2017)

[There is an updated version of the map and commentary below, see here]

About this Map and Urban Chinese Temples

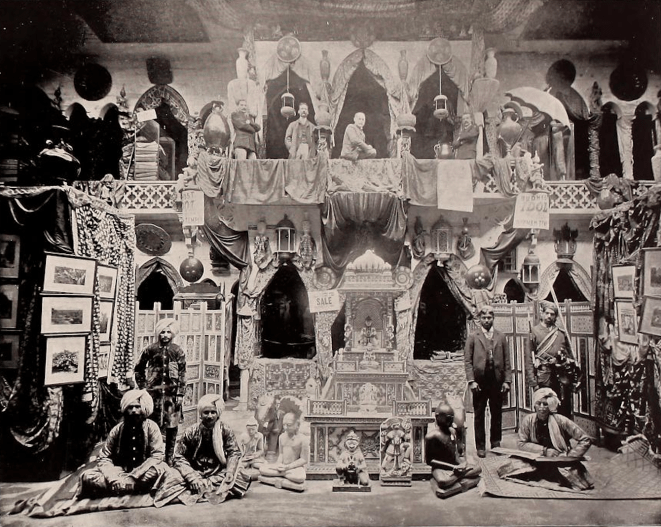

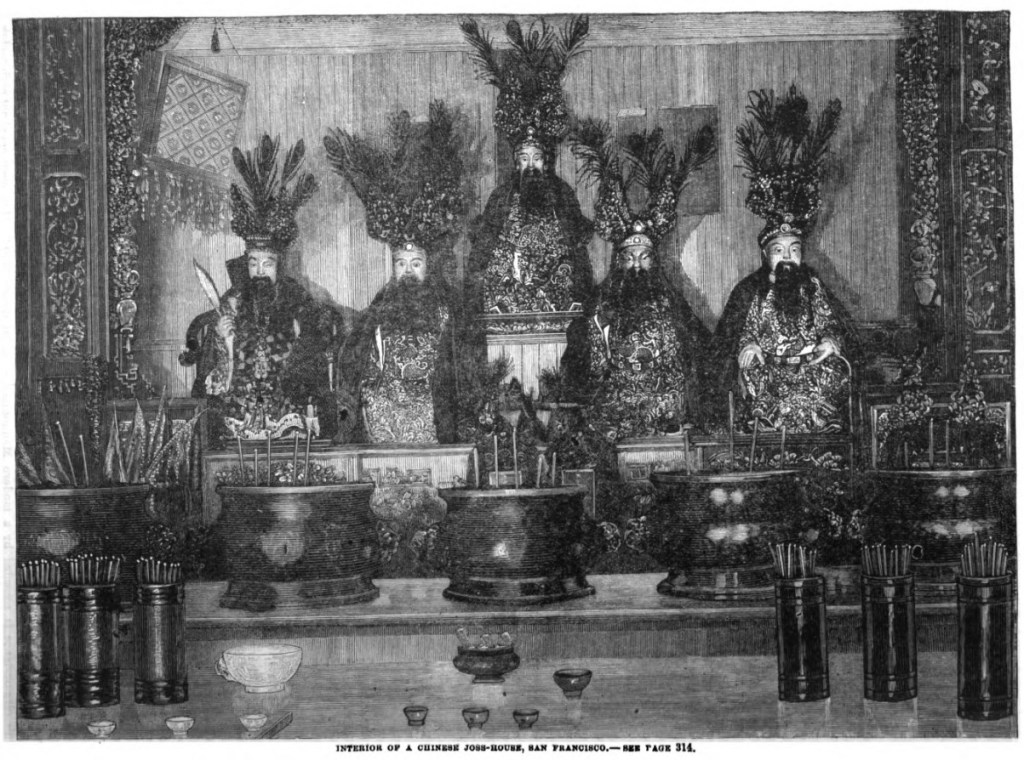

This map locates many of the Chinese temples built in San Francisco before the 1906 earthquake and fire. Known generically as miao 廟 (or miu in Cantonese), meaning temple or shrine, most of the non-Chinese American public referred to these structures as “joss houses” in the nineteenth century. A principle function of these temples, from which their American names derived, was to house Chinese religious icons, commonly called “joss.” Rarely, however, did urban temples occupy a whole building; temples were more typically semi-public shrine halls located on the top floor of a multi-story structure. Moreover, these temples were not operated by religious institutions and almost all were owned and operated by various community organizations. Often the largest temples were operated by different district associations (huiguan 會館), while other temples were run by secret fraternal organizations (tang 堂) or various other associations organized around clan lineages or trades. A few seem to have operated as semi-independent institutions. Most temples housed numerous icons that would be worshiped for an array of reasons, but often a temple would be “dedicated” to a single figure who functioned like the patron deity of the association or guild. This icon was typically placed in the central shrine of the main shrine hall. The other floors of the building could have smaller shrines or be used as meeting rooms and work spaces for the organization.

About this Project

Much of the nineteenth and early twentieth photography and illustrations of Chinese religious sites remain unidentified because they are often labeled or captioned as generic “joss houses.” To facilitate identification, I compared contemporary written accounts with items from the visual record of Chinatown and cross referenced them with maps and listed addresses of known temples. The end product was the identification of many images of unknown religious sites and the location of several temples of which we only had a written description. I’m publishing here my working notes for a basic map of the Chinatown temples I have identified. I used the 1885 San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors’ Map as the basis for the main map (directly below) and the 1887 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map and the 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map to help track changes over time. Ultimately, this is the byproduct of a larger project I am currently working on regarding the material culture of early Asian American religions with a focus on early American Buddhist traditions.

*April 2021 Update: Chuimei Ho provided me with some invaluable insights noted below.

*March 2022 Update: I direct all interested readers on this topic to the new publication: Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson, Chinese Traditional Religion and Temple in North America, 1849–1920: California (Seattle: Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee, 2022). It combines newspaper and periodical accounts, surviving temple records, and oral histories to create the most up-to-date picture of early Chinese religious life in California.

*March 2024 Update: Some of the information below helped form my arguments presented “Buddhist Material Culture in the United States,” in The Oxford Handbook of American Buddhism, eds. Ann Gleig and Scott Mitchell, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 462–482.

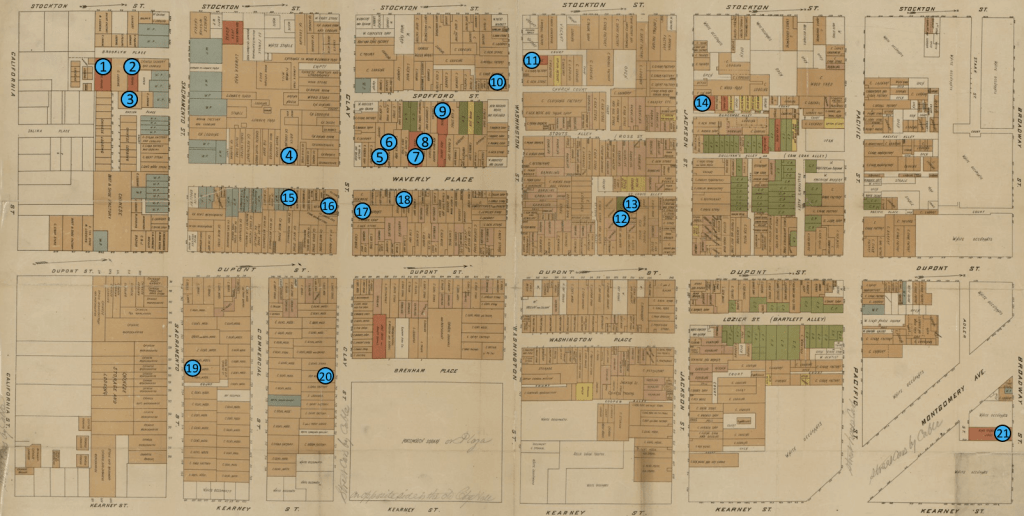

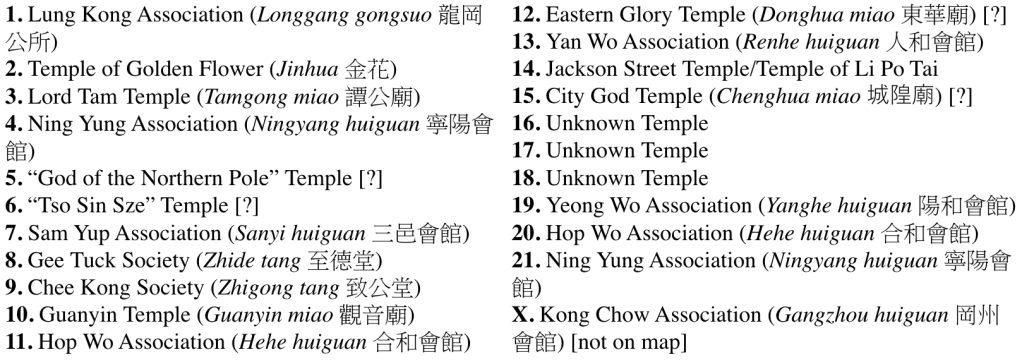

Map

Numbers on the map correspond to the temples listed in the key below. A “[?]” indicates that I have not been able to identify an exact address for the temple and its placement on the map is approximate. The last temple marked with an “X” was located on Pine Street which is not included on this map. I have decided to keep the Romanization for the organizational names as they appear today (even if they no longer operate temples in San Francisco) and provide the Pinyin with Chinese characters in parenthesis. Lastly, this map is syncretic, not all of the temples existed at the same time; please see individual temple descriptions below.

Map of Temples in San Francisco’s Chinatown: 1850s-1906

Highlights

Some of oldest temples in Chinatown are thought to be the Sam Yup building shrine [#7], more popularly known as the Tin How Temple (Tianhou miao 天后廟) and the Kong Chow temple [#X], both believed to have been constructed in the early 1850s, though not without some dispute. Waverly Place, the two-block road between Sacramento Street and Washington Street, was known among the Chinese as Tin How Temple Street (Tianhou miao jie 天后廟街) and became the home to the greatest density of Chinese temples by the 1890s. The most popular sites for tourists were the two locations of the Ning Yung temple [originally at #21, then at #4], the original Hop Wo headquarters and temple [#20], and the Yeong Wo temple [#19].

Among the temples listed on the map where the central icon can be identified, three were dedicated to the semi-historical figure Guandi 關帝 [#21/#4, #20/#11, #X], two were dedicated to the Empress of Heaven (i.e. Tianhou), also known as the goddess Mazu 媽祖 [#7, #14], and one to the popular Buddhist figure Guanyin Bodhisattva [#10]. Another popular icon was the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heavens (Xuantian shangdi 玄天上帝), also known as the Emperor of the North (Beidi 北帝), whose icon I suspect may have traveled between two or three different locations [#12, (#14?), #8], in addition to having his own temple in the 1890s [#5]. Among the numerous fraternal societies that operated temples [including #16, #17, #18], the Chee Kong Society [#9] and Gee Tuck Society [#8] operated two of the most popular.

Selected Temples (With selected Information and Imagery)

1. Lung Kong Association (Longgang gongsuo 龍岡公所)[9 Brooklyn Place]: the central icons were five glorified cultural heroes, Liu Bei 劉備 (center), Guan Yu 關羽 (center right), Zhang Fei 張飛 (center left), Zhao Yun 趙雲 (far right), and Zhuge Liang 諸葛亮 (far left)[for more on the image below, see here]

2. Temple of Golden Flower (Jinhua 金花)[4 Brooklyn Place]: the central icon was Lady Golden Flower (Jinhua niangniang 金花娘娘), a figure known to protect the health of women and children

3. Lord Tam Temple (Tamgong miao 譚公廟)[Oneida Place]: the central icon was Lord Tam, often considered a patron saint of seafarers, this temple was in existence in 1892

4. Ning Yung Association (Ningyang huiguan 寧陽會館)[25 Waverly Place]: constructed around 1890, the central icon was Guandi [see also #21]

7. Sam Yup Association (Sanyi huiguan 三邑會館)[33 Waverly Place]: Possibly operating as an independent temple, the central icon of the Tin How Temple was Tin How (the Empress of Heaven, also known as Mazu); the temple is believed to have opened in 1852, per claims in the 1890s, but there is no corroborating evidence to support this early date

8. Gee Tuck Society (Zhide tang 至德堂)[35 Waverly Place]: The central icon was possibly the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heavens [*04/2021: Chuimei Ho kindly notes this icon was on the top floor, not associated with the Gee Tuck shrine on second floor]; this shrine was in existence by the mid 1880s.

9. Chee Kong Society (Zhigong tang 致公堂)[32 (or 69) Spofford Street]: the central icon remains unknown

10. Guanyin Temple (Guanyin miao 觀音廟)[60 Spofford Street]: the central icon was Guanyin

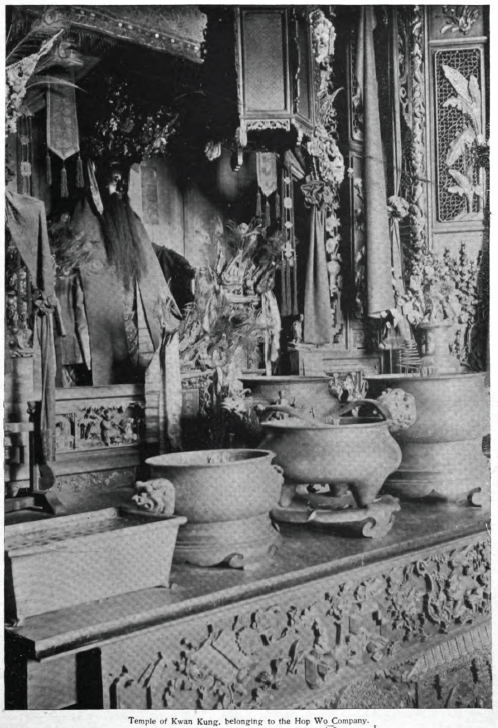

11. Hop Wo Association (Hehe huiguan 合和會館)[840 Washington Street] the location of the Hop Wo Association headquarters in the mid-1880s, I am unsure if they had a temple at this address as well [see also #20]

12. Eastern Glory Temple (Donghua miao 東華廟)[possibly 929 Dupont Street]: opened in 1871, a central icon was the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heavens

13. Yan Wo Association (Renhe huiguan 和會館)[St. Louis Alley/933 Dupont Street]: the central icon was possibly the Buddhist heavenly king Virūpākṣa (Guangmu tianwang 廣目天王) [*4/2021 update: some sources claim it was Guandi]

14. Jackson Street Temple/Temple of Li Po Tai [730 Jackson Street]: a central icon was the Empress of Heaven or possibly at one time the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heavens; the famed Chinatown physician Li Po Tai (Li Putai 黎普泰), I conjecture, may have owned this temple, thus tracing its opening to the early 1870s

19. Yeong Wo Association (Yanghe huiguan 陽和會館)[approx. 728 Sacramento Street]: the central icon was the semi-historical figure Houwang 侯王

20. Hop Wo Association (Hehe huiguan 合和會館)[751 Clay Street]: in existence by 1876 if not much earlier, the central icon was Guandi [see also #11]

21. Ning Yung Association (Ningyang huiguan 寧陽會館)[517 Broadway Street]: constructed in 1864 and used until around 1890, the central icon was Guandi [see #4]

X. Kong Chow Association (Gangzhou huiguan 岡州會館)[512 Pine Street]: constructed in 1853, the central icon was Guandi

Online Resources:

Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (http://www.cinarc.org/index.html): This group published an initial map of Chinatown organizations in 2018 [here], upon which I have expanded and fine-tuned. I owe the initial impetus of creating a temple map to the outstanding editors of that website.

Additional “Working Notes” Posts