Peter Romaskiewicz

*January 2026: Updating from 34 temples to 45 temples in progress! Thank you for your patience.*

Dedicated to Philip Choy (1926–2017)

About this Map and Urban Chinese American Temples

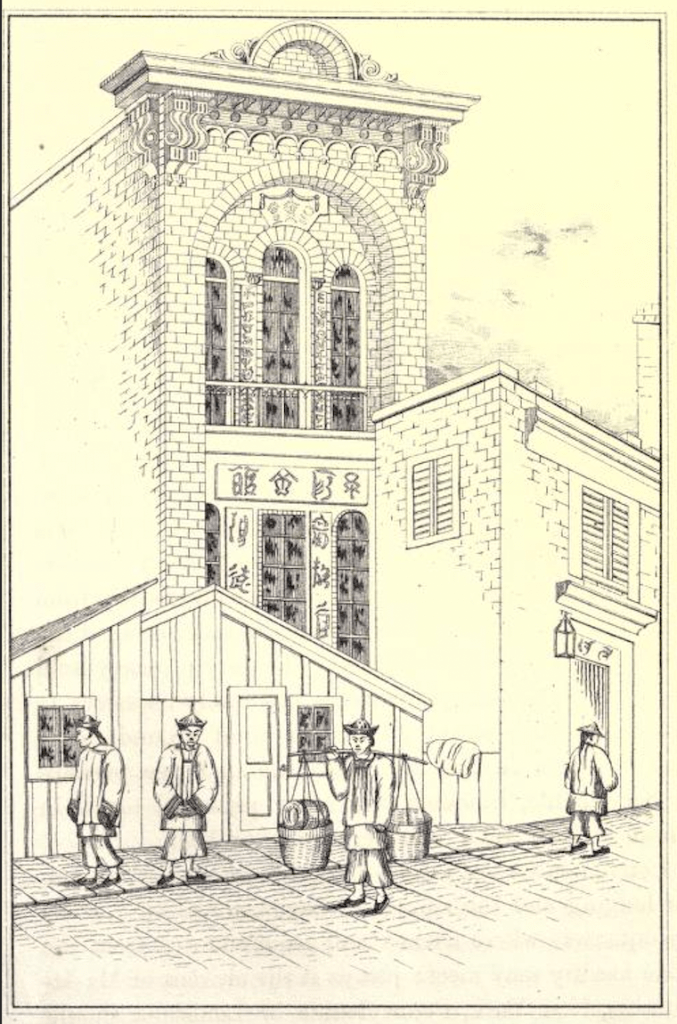

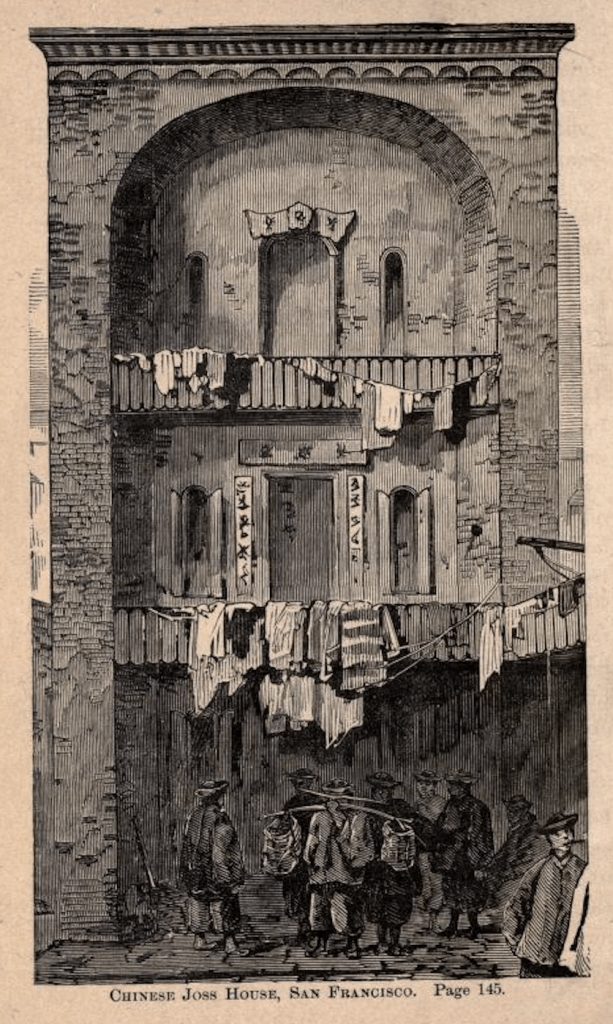

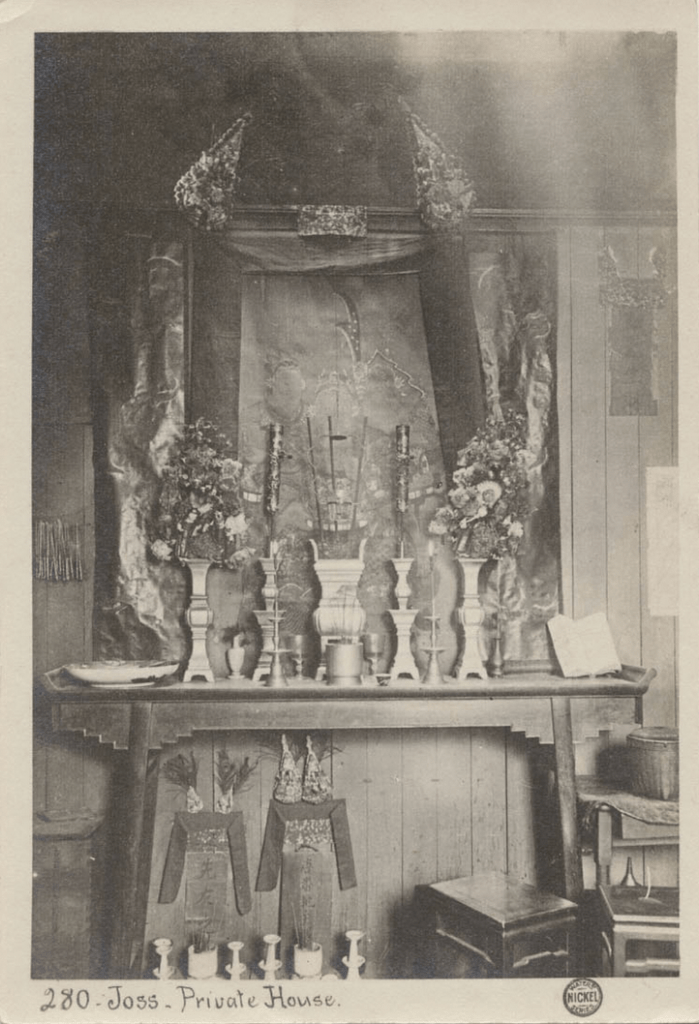

This map and commentary identifies many of the Chinese temples constructed in San Francisco prior to the 1906 earthquake and fire. Known generically as miao 廟 (or miu in Cantonese), meaning temple or shrine hall, these structures were commonly referred to as “joss houses” by the non-Chinese American public. A principal function of these temples was to enshrine Chinese religious icons, known commonly as “joss,” and house other ritual equipment relevant to religious practice and worship.

Urban Chinese American temples rarely occupied a whole building. More typically, they took the form of shrine halls on the top floor of a multi-story structure. Moreover, these early temples were not operated by religious institutions, but were owned and operated by various community organizations. A handful seem to have been privately owned and managed. The largest, most opulent temples were often maintained by district associations (huiguan 會館), while many others were operated by secret fraternal organizations (tang 堂) or by associations organized around clan lineages or particular trades.

Many temples, especially those in private hands, enshrined numerous icons that could be worshiped for an array of reasons. In other cases, a temple was dedicated to a single figure who functioned as the patron deity of the association or guild. This icon was placed in the central altar of the main shrine hall. In larger district association buildings, the lower floors were typically devoted for non-religious functions, such as meeting rooms, hostels, or other work and business spaces essential for the organization’s operation.

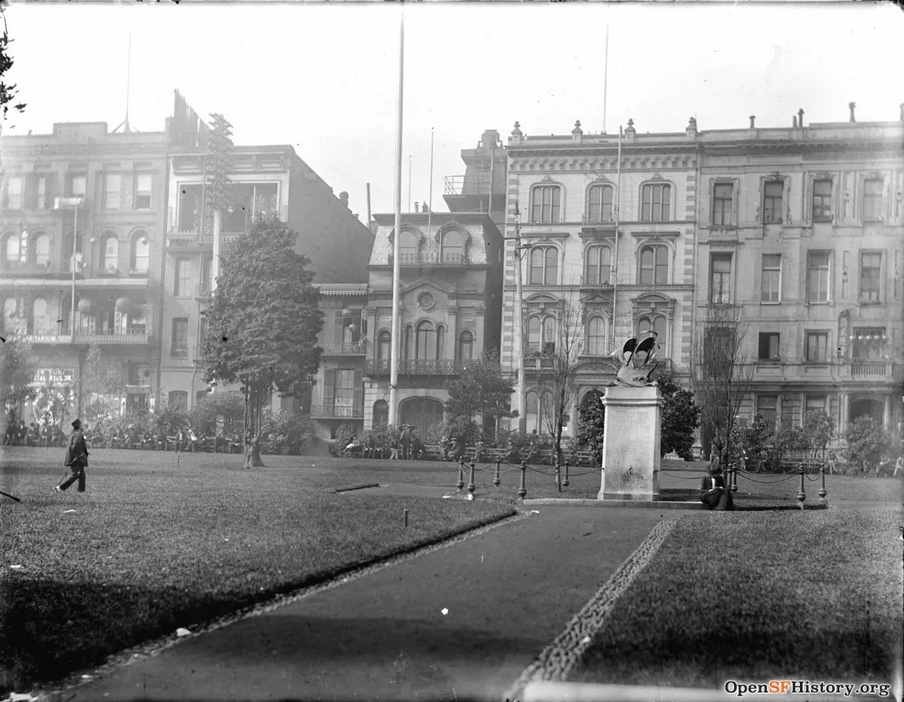

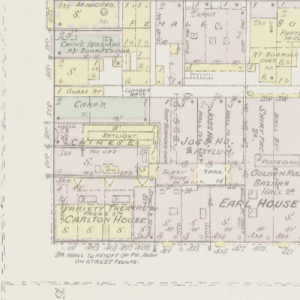

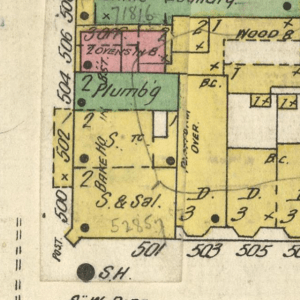

The base map used here is the 1887 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map. It is accompanied by brief commentary and related imagery from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries depicting the exterior and interior of selected temples.

May 2025 Update: Significant revisions to map and commentary. I’ve archived the older post here. January 2026 Update: Revised & expanded map and commentary.

Map of Temples in San Francisco’s Chinatown: 1850s-1906

![District Associations

2. Yeong Wo Association II (Yanghe huiguan 陽和會館)

6. Ning Yung Assoc. II (Ningyang huiguan 寧陽會館)

12. Sam Yup Assoc. II [?] (Sanyi huiguan 三邑會館)

15. Sam Yup Association I (Sanyi huiguan 三邑會館)

24. Sam Yup Association III (Sanyi huiguan 三邑會館)

25. Yan Wo Association II (Renhe huiguan 人和會館)

35. Yeong Wo Assoc. III (Yanghe huiguan 陽和會館)

36. Six Companies I (Zhonghua huiguan 中華會館)

36. Hop Wo Association I (Hehe huiguan 合和會館)

37. Six Companies II (Zhonghua huiguan 中華會館)

38. Hop Wo Association II (Hehe huiguan 合和會館)

45. Ning Yung Assoc. I (Ningyang huiguan 寧陽會館)

X1. Yeong Wo Assoc. I (Yanghe huiguan 陽和會館)

X2. Sze Yup Association (Siba huiguan 四邑會館) Kong Chow Association (Gangzhou huiguan 岡州會館)

Clan Associations

1. Lung Kong Assoc. (Longgang gongsuo 龍岡公所)

3. Lord Tam Temple (Tamgong miao 譚公廟)

14. Yee Fung Toy Soc. (Yufengcai tang 余風采堂)

14. Gee Tuck Society (Zhide tang 至德堂)

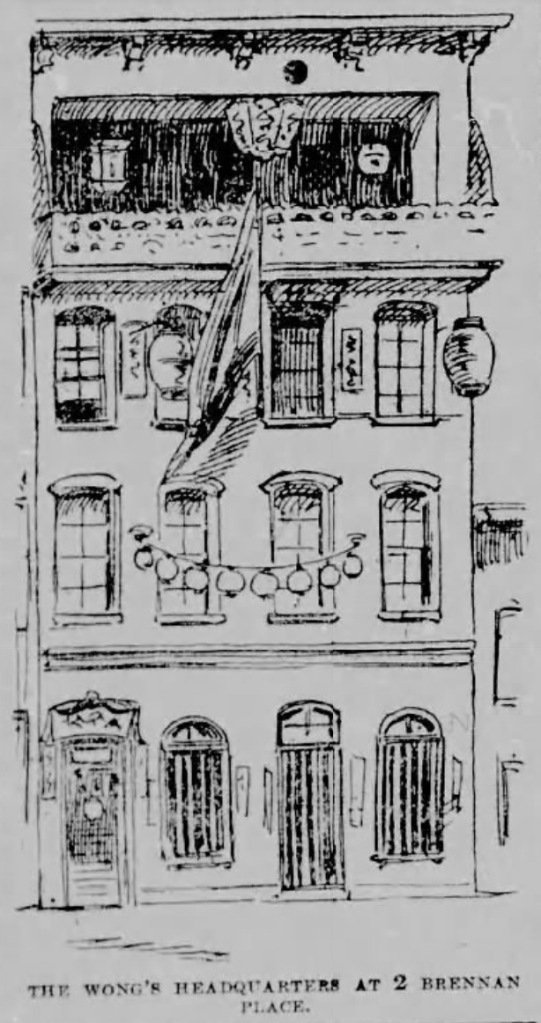

17. Wong Kong Ha Shrine II (Huang jiangxia黃江夏)

40. Wong Kong Ha Shrine I (Huang jiangxia黃江夏)

Privately Owned Temples

2. Temple of Golden Flower (Jinhua miao 金花廟)

7. City God Temple I (Chenghua miao 城隍廟)

12. Tin How Temple (Tianhou miao 天后廟)

14. Eastern Glory Temple II (Donghua miao 東華廟)

18. Guanyin Temple (Guanyin miao 觀音廟)

22. Eastern Glory Temple I (Donghua miao 東華廟)

23. City God Temple II (Chenghua miao 城隍廟)

28. Jackson Street temple

30. Voorman’s building shrine

31. Sullivan’s building shrine

39. Chan Master Temple (Chanshi miao禪師廟)

39. City God Temple III (Chenghua miao 城隍廟)

X3. Ah Ching’s Tin How Temple (Tianhou miao 天后廟)

Secret Societies

8. Hong Sing Society

10. Dock Tin Society

11. Suey On Society (Ruiduan tang 瑞端堂)

12. Hip Yee Society (Xieyi tang協義堂)

13. Hip Sing Society (Xiesheng tang 協勝堂)

16. Chee Kong Society (Zhigong tang 致公堂)

19. Kai Sen Shea Society (Jishanshe tang 繼善社堂)

20. Bing Kong Society I (Binggong tang 秉公堂)

27. Bing Kong Society II (Binggong tang 秉公堂)

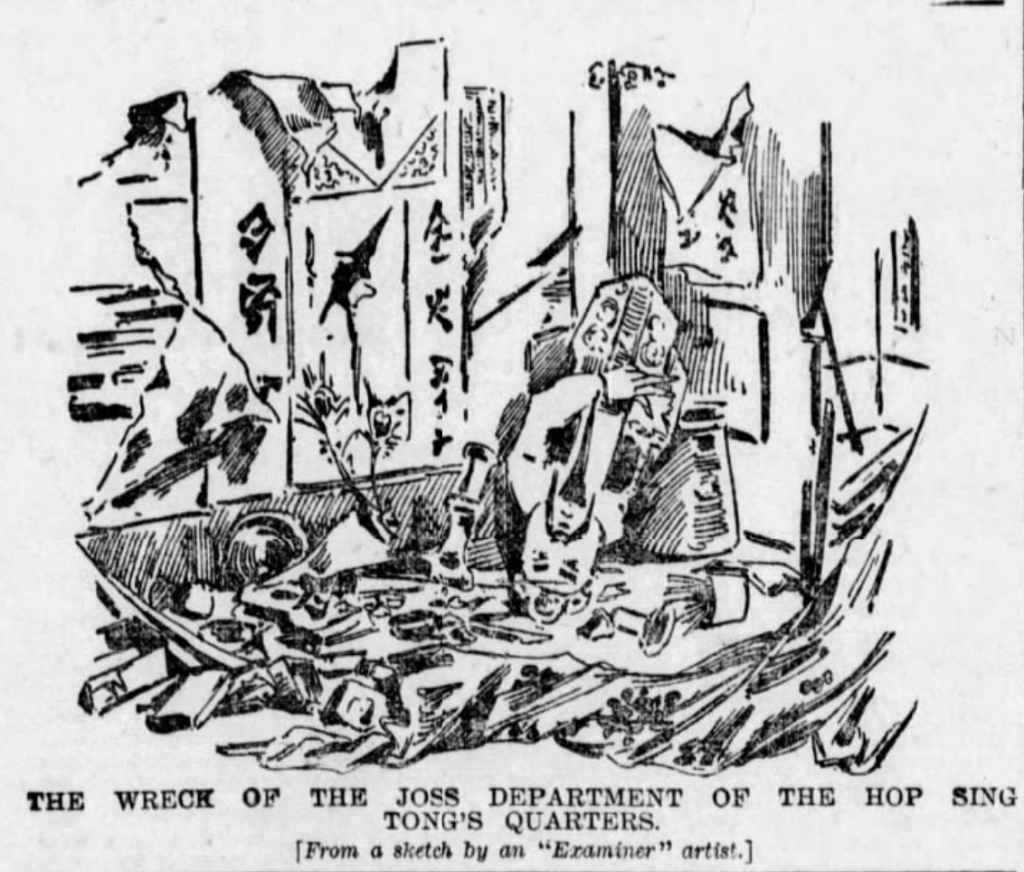

32. Hop Sing Tong (Hesheng tang 合勝堂)

33. On Yick Tong (Anyi tang安益堂)

39. Suey Ying Society (Ruiying tang 瑞英堂)

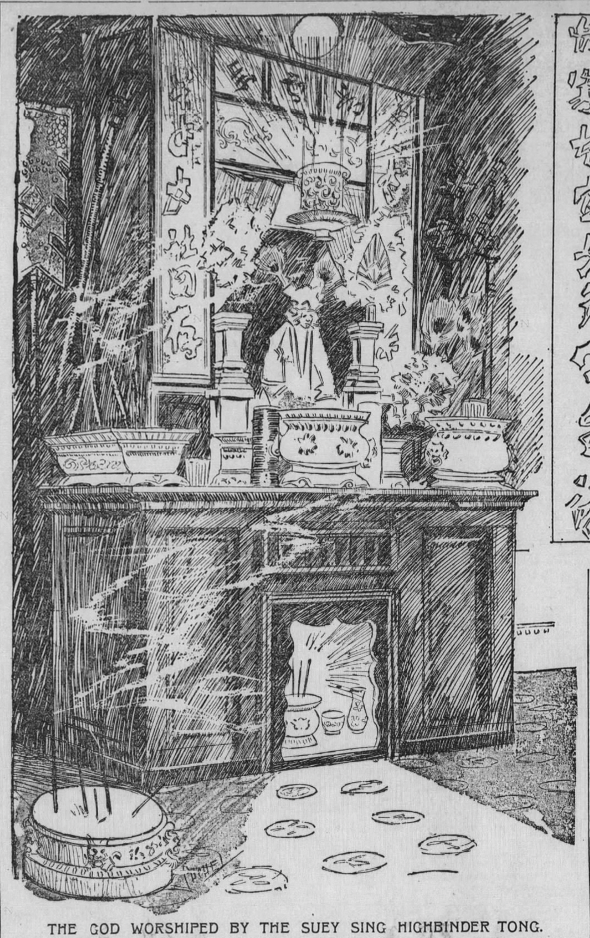

44. Suey Sing Tong (Cuisheng tang 萃勝堂)

Guild Shrines

4. Washermen’s shrine

34. Chinese Merchant’s Exchange shrine

40. Tailor’s shrine

Other

5. Hang Far Low Restaurant shrine

21. Grand Chinese Theatre shrine

26. St. George Temple

29. Yuen Fong Restaurant shrine

42. Chinese Telephone Exchange shrine

43. New Chinese Theatre shrine](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/san-francisco-chinatown-temple-map-legend-romaskiewicz-jan-2026.png)

Notes to the Map and Key

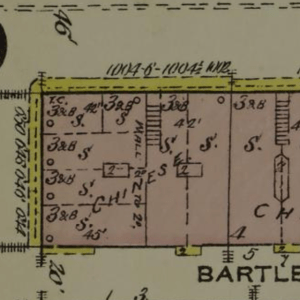

Temples and shrines are arranged by type following Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson (2022). Importantly, this map is syncretic; not all temples and shrines existed simultaneously. Many temples relocated within Chinatown over time (indicated by I, II, etc.), sometimes taking up residence in older temple buildings. The identification of multiple temples at a single address might indicate shared use of a building, such as occupancy on different floors, or successive occupation in different periods; these issues are addressed in the brief commentary below. Please note the map is oriented with north pointing to the right.

The three locations in the key marked with an “X” fall outside the boundaries of this map, please refer to the section below covering San Francisco temple locations beyond Chinatown.

Historical Overview of Chinatown’s Temples

Oldest Temples

The oldest temples in San Francisco’s Chinatown are often thought to be the Tin How Temple on Waverly Place [#12] and the Kong Chow temple originally on Pine Street [#X2]. Both are claimed to have been built in the early 1850s, but this is not without some dispute and qualification.

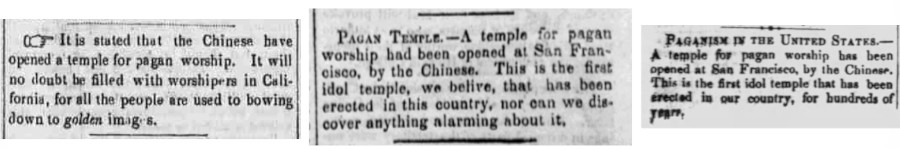

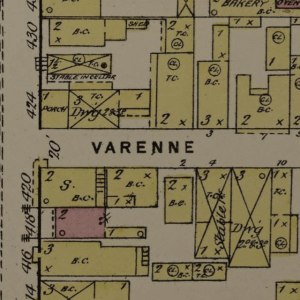

As shown by Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson, the earliest report of a Chinese temple in San Francisco – variously characterized as a heathen, pagan, and idol temple in contemporary newspapers – appears in the fall of 1851. Unfortunately, the brief account repeated by newspaper editors across the US provides scarce detail regarding location or affiliation [Figs. 1–3]. The earliest identifiable temple structure is connected with the Yeong Wo Association, built on the southwestern slope of Telegraph Hill and dedicated in the fall of 1852 [see #35]. It is now possible to confirm that this Yeong Wo temple was the same as the unnamed Chinese “idol temple” described in 1851 and was located on Varennes Street [see #X1].

The Yeong Wo temple predates the Sze Yup Association temple, which is sometimes mistakenly identified as the first Buddhist temple in the United States. The Sze Yup Association was formally organized in 1851 and constructed its headquarters and temple near Pine Street and Kearny Street two years later, in 1853. In the mid-1860s, this building became the legal property of the Kong Chow Association, an organization composed of members from Xinhui in Guangdong Province, one of the four constituent groups that originally formed the Sze Yup Association. This relationship helps correct the common misconception that the Kong Chow temple was built in 1851, clarifying instead that it was constructed in 1853 by its parent organization, the Sze Yup Association.

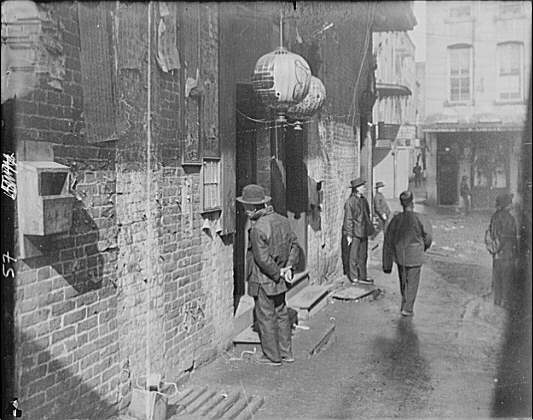

Despite the widespread claim that the Tin How Temple on Waverly Place dates to the early 1850s, no contemporary historical documentation supports this assertion. The earliest evidence for a Tin How Temple on Waverly appears in June 1877, while the name “Tin How” first appears in a property sale record from 1876. Notably, however, by June 1877 Waverly Place—the two-block street connecting Sacramento and Washington Streets—was already known among the Chinese community as Tin How Temple Street (Tianhou miao jie 天后廟街). This area would later contain the highest concentration of Chinese temples prior to the 1906 earthquake.

Significant Temples and Icons

While the Tin How and Kong Chow temples are today regarded as among the most prominent in Chinatown – both among the rare organizations to rebuilt temples after the earthquake and fire – an examination of historical media coverage, travel accounts, and visual representations of San Francisco’s Chinese religious landscape reveals a far more complex historical picture. As Chinatown grew and developed through the nineteenth century, different temples garnered attention at different times, with some falling into obscurity after periods of relative prominence.

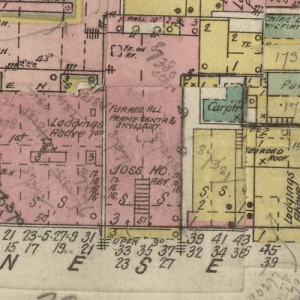

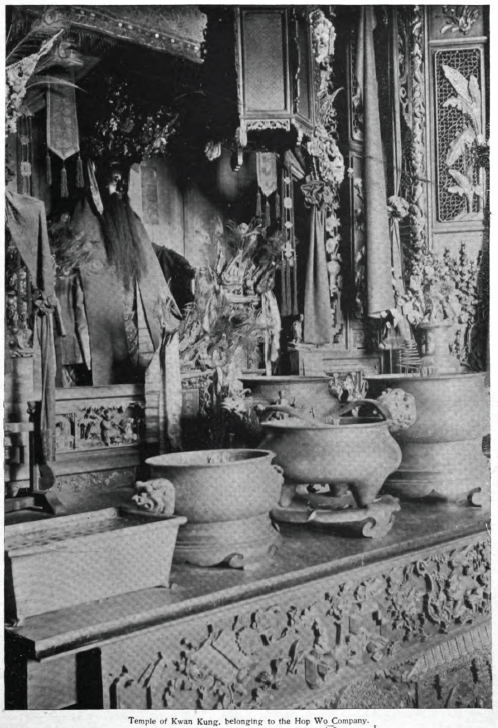

One of the first temples to receive media attention was the Sze Yup Association temple upon its opening in 1853 [#X2]. Substantial attention next fell on the Ning Yung Association temple in 1864 [#45], in part because its opening was described by the young Samuel Clemens, later known as Mark Twain. During the 1860s, this temple was widely regarded as the primary “joss house” for tourists, owing in part to its proximity to the newly built Globe Hotel at Dupont and Jackson Streets. In the following decade, significant media and guidebook attention shifted first to the privately owned Eastern Glory Temple in 1871 [#22], located on St. Louis Alley, and then towards the new and lavishly decorated Hop Wo Association temple on Clay Street after 1874 [#38]. When the Yeong Wo moved from their old building on Brooklyn Place [#2] to their new site on Stockton Street in 1887 [#35], they also began attracting more outside visitors and curious onlookers, in part due to the festive parades held in honor of their main icon. Lastly, when the Ning Yung moved to their new temple on Waverly [#6] in 1891, in the religious heart of Chinatown, they were considered the most opulent and worthy of tourist visitation. After the turn of the twentieth century, self-guided walking tours through Chinatown also noted the beauty of the newly constructed Wong family temple, also on Waverly [#17]. After rebuilding and reopening in 1911, the Tin How Temple was seen as a reminder of old Chinatown, especially as many of the older temples and shrines halls were never rebuilt.

Restricting ourselves to the temples listed here where a main icon can be identified, the semi-historical figure Guandi 關帝 emerges as the most commonly enshrined deity [#6/#45, #38, #25, #X2, and nearly all secret societies). Two, or possibly three, temples focused devotion to the Empress of Heaven (i.e. Tianhou 天后), also known as the goddess Mazu 媽祖 [#12, #28, #X3], and two temples were dedicated to the popular Buddhist bodhisattva Guanyin 觀音 [#18, #40]. Icons of Guanyin and Tianhou also appeared in several temples as secondary figures, placed in flanking positions on the main altar or housed in adjacent altars, rooms, or floors [#2, #22, #X3]. Another important figure was the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heavens (Xuantian shangdi 玄天上帝), also known as the Northern Emperor (Beidi 北帝), whose icon traveled with the movement of the Eastern Glory Temple [#22, #14]. Among the numerous fraternal societies that operated temples, the Chee Kong Society [#16] was by considerable margin the most influential.

Buddhist Icons in Chinatown

It is worth noting that I have not encountered a reliable written report, illustration, or photograph of Śākyamuni or Amitābha Buddha statues in any pre-1906 Chinese temple in San Francisco. Despite frequent tourist accounts describing encounters with “the Buddha” in Chinatown temples, such references can be attributed to misunderstanding or mis-identification. In most cases, the figure described was likely Guandi or the Northern Emperor. In other instances, the term “buddha” appears to have been used interchangeably with “joss” with no more precise meaning than “Chinese idol.” Visual depictions of buddhas sitting on San Francisco’s Chinatown altars appear only in political cartoons, crude newspaper sketches, and other poorly informed visual caricatures of Chinese immigrant life in the late nineteenth century (see, for example, #6)

In contrast to the limited ritual nature of community organization temples and shrine halls, many of which prominently displayed Guandi, privately owned temples seemed to hold more latitude for enshrining a wider variety of icons, including Buddhist ones. In this regard, the figure of Guanyin played a central role in the religious life of many early Chinese immigrants, being found in five locations on this map and likely remaining unreported at many others. At least one observer in 1883 claimed Guanyin occupied a “prominent corner of every private home as well as temple.” Images of the Buddha, by contrast, found no comparable level of popular support among early Chinese immigrants in San Francisco. This conclusion is further supported by the absence of any Chinatown-wide celebration for the Buddha’s birthday in either 1873 or 1880, when we have year-long records for important Chinwtown festivals, or documentation for this event in San Francisco newspapers any other year before 1906. Consequently, images of buddhas in other temples across California, such at the Oroville temple complex built by the powerful Wong clan [see #40], should be considered meaningful exceptions to the typical landscape of early Buddhist material culture in the United States.

Note on Temple Commentary

A brief note on dating used below is warranted. Secondary scholarship covering the history of Chinatown’s temples often presents differing founding dates for the same institution. Sometimes this is due to historical complexities, such as when organizations split or descended from older institutional bodies. Furthermore, these discrepancies might be due to a conflation between the formal organization of a district association and the physical construction of its district association building, two distinct events that may be separated by many years. For example, while the Ning Yung Association organized in 1853, after splitting from the older Sze Yup Association, the earliest mention of an Ning Yung building with shrine hall is 1864, an eleven-year gap. My focus here is on the construction of temple buildings themselves, events that were often reported with fanfare in the contemporary press and that allow us to examine the reception and influence of Chinese religious material culture in the United States. On another hand, not only did the 1906 earthquake and fire destroy Chinatown’s religious buildings, but also almost all district association and fraternal society records. As a result, some temples or associations that claim early origins in the United States rely primarily on oral histories or much later historical documentation. While such accounts are valuable, they must be evaluated in conjunction with the earliest surviving documentary evidence which sometimes reveals a different story.

As of this writing, the most comprehensive study of the history of Chinese temples in San Francisco is Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson’s Chinese Traditional Religion and Temples in North America, 1849–1920: California (2022). I have benefited greatly from their expansive and nuanced historical research and archival work, which has helped resolve many longstanding questions and uncertainties; several of the observations presented here extend or supplement their critical analysis.

Selected Temples with Commentary and Imagery

1. Lung Kong Association (Longgang gongsuo 龍岡公所)

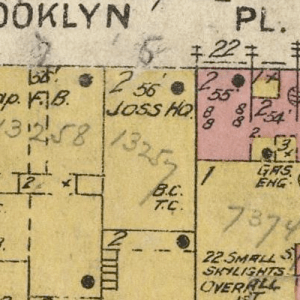

9 Brooklyn Place | 1887 Sanborn

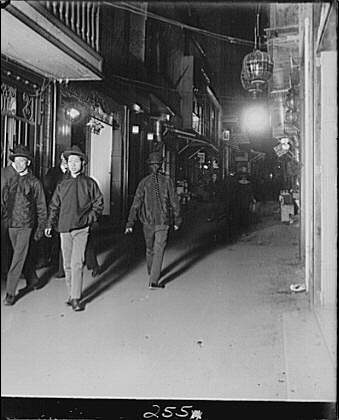

The two-story Lung Kong building, located near the mid-point of Brooklyn Place between Sacramento and California streets, opened in the mid-1880s. The Long Kong Association was, and remains, an important clan association. Though similar in function to district associations, Lung Kong membership was not based on native districts, but from clan lineage, specifically serving members of the Lau/Lew 劉 (Liu), Kwan/Quan 關 (Guan), Cheong/Jeong 張 (Zhang), and Chin/Chew 趙 (Zhao) families. This set of four family lineages was not accidental, as each name can be traced to figures who played a prominent role in Chinese history during the period of the Three Kingdoms (220-280), namely Liu Bei, Guan Yu, Zhang Fei, and Zhao Yun. According to association history, members of these four families founded a temple in the seventeenth century in the Kaiping district of Guangdong province before organizing in the United States in 1875. No records survive, however, supporting this date of 1875 and the first appearance of this association in US media is through the announcement of a celebration at its temple on Brooklyn Place in the summer of 1886.

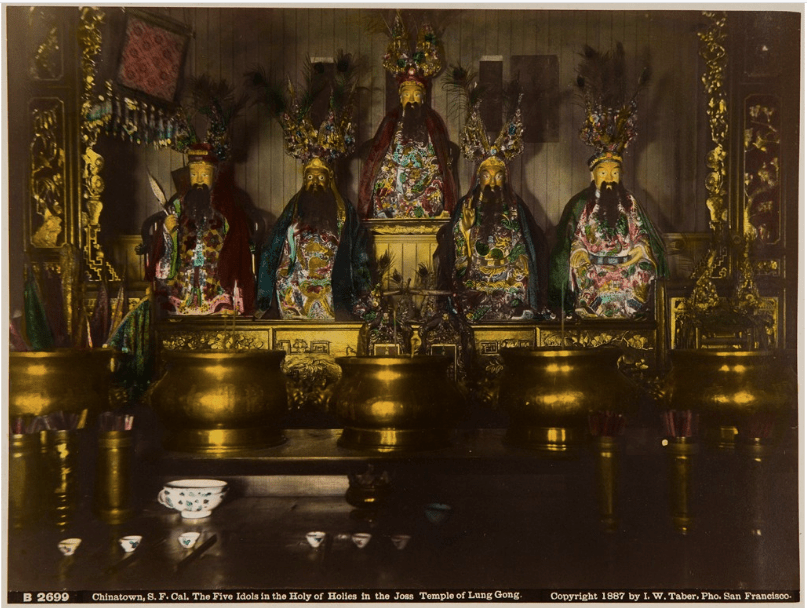

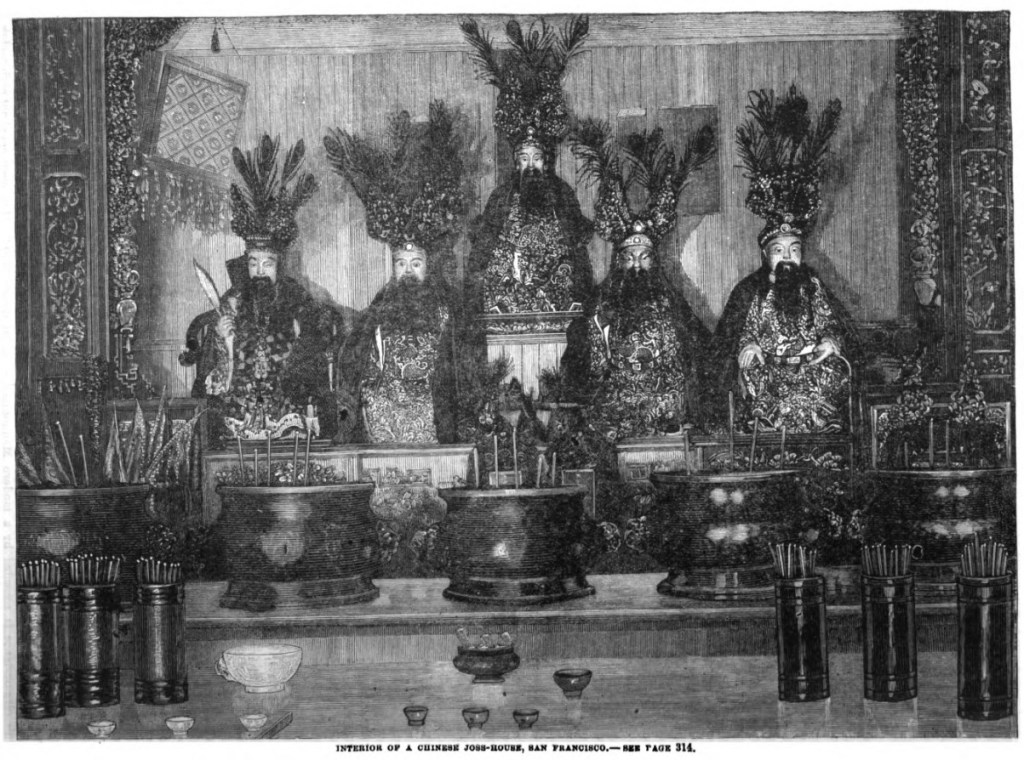

San Francisco-based photographer Isaiah West Taber (1830–1912) was able to capture the Long Kong Association shrine hall and altar in 1887 (see below), a rare interior image of a early Chinese American temple. The central icons were five glorified cultural heroes, Liu Bei (center), Guan Yu (center right), Zhang Fei (center left), and Zhao Yun (far right), with the addition of Zhuge Liang 諸葛亮 (far left).[For more on Taber’s photograph and it’s continued biography as a postcard, see here]. One visitor in 1887 describes the shrine hall as a “beautiful room with a large window opening on to a balcony,” with five figures displayed at the furthest end of the room. These icons are identified as “wood painted a bronze red, with fierce black mustaches and almond shaped eyes.”

Taber’s photograph showing a closely cropped image of the altar was repurposed for the cover to William Bode’s Lights and shadows of Chinatown in 1896. A second Taber photo shows the placement of the incense offering table before the main altar, obscuring most of the view of the icons. This furniture arrangement was standard among early Chinese American temples.

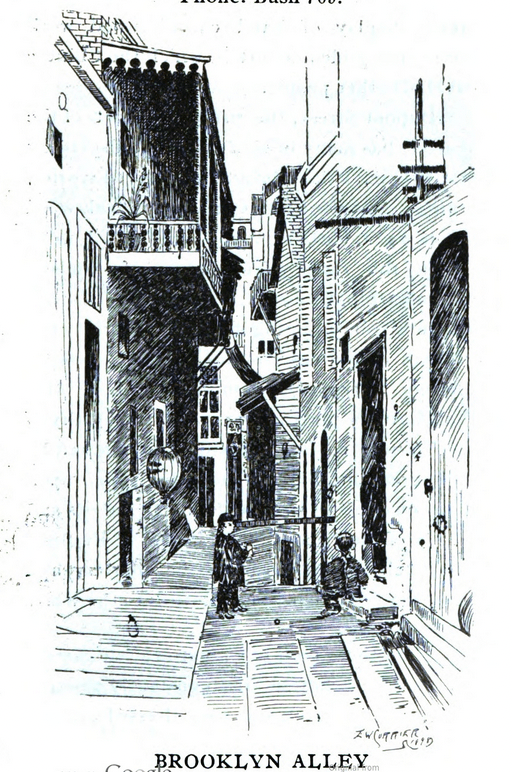

As for the building exterior, a simplistic sketch from Edward Wilson Currier (1857–1918) possible shows the temple’s two-story brick edifice. This was published in a San Francisco guidebook in 1898. It appears Arnold Genthe (1869–1942) may have also taken a photograph looking the opposite way down Brooklyn, just capturing the temple’s lanterns (see both below). All temple records and artifacts were lost in the 1906 earthquake.

The Long Kong Association rebuilt after 1906 at a different location and is still in operation today under the name Lung Kong Tin Yee Association.

2. Yeong Wo Association I (Yanghe huiguan 陽和會館) / Temple of Golden Flower (Jinhua 金花)

4 Brooklyn Place | 1905 Sanborn

This small two-story building on Brooklyn Place served as the headquarters of the Yeong Wo Association from at least 1883, when it hosted the inaugural Chinatown parade for the association’s principal icon. The association relocated to its more permanent quarters on Sacramento Street in 1887 [#35].

At some point thereafter, the building was taken over by a privately owned temple that Frederic Masters described as being “crowded with images of goddesses, mothers, nurses, and children.” The central icon was Lady Golden Flower (Jinhua niangniang 金花娘娘), a deity revered for protecting the health and well-being of women and children. This figure was flanked by Guanyin and Tianhou on the altar. Additionally, eighteen attendant wet nurses (nainiang 奶娘) of Lady Golden Flower were arranged along the walls of the temple.

A description of Chinatown from 1883, prior to the opening of the temple to Lady Golden Flower, notes that images of the goddess, depicted holding a child in each arm, were placed beneath the beds of infants throughout Chinatown. Altars dedicated to Lady Golden Flower were also established within other independent temples, including Ah Ching’s Tin How Temple [#X3] and Eastern Glory Temple on St. Louis [#22]. Moreover, the birthday of Golden Flower (17th day of 4th lunar month) was widely celebrated across the Chinese quarter. The figure of Lady Golden Flower was clearly among one of the most important deities in Chinatown, but remains one of its most poorly understood.

The 1885 Board of Supervisors’ Map identifies a joss house at this location, most likely referring to the Yeong Wo temple. By contrast, the 1887 Sanborn Map shows no temple at this address, suggesting that it was prepared after the Yeong Wo Association, had moved but before the Golden Flower Temple was established.

The Golden Flower Temple was not apparently rebuilt following the 1906 earthquake.

3. Lord Tam Temple (Tamgong miao 譚公廟)

Oneida Place | 1887 Sanborn

This three-story clan association temple served the Tam (Tom) families and was in existence by the late 1880s, though Frederic Masters reputed it to be among the oldest temples in Chinatown. Located on Oneida Place, the temple’s central icon was Lord Tam (Tamgong 譚公), a deity often regarded as a patron of seafarers and – at least in the context of Chinatown – also of theatrical troupes. Lord Tam is closely associated with the Hakka, a minority ethnic group within the broader Chinese diaspora. The entrance to the temple was painted by Charles Albert Rodgers in 1901 [viewable here].

4. Washerman’s Guild Shrine

825 Sacramento | 1887 Sanborn

Several washermen’s guilds operated in Chinatown, but one early organization, simply known as the “Washermen’s Association,” was known to meet regularly on Oneida Place. A newspaper account from 1870 reports that the guild’s meeting room and joss house was located at the rear of a two-story building at 825 Sacramento Street, accessible via a narrow stairway off Oneida Place. This is one of the earliest institutionally-owned shrines reported in Chinatown, with the others being only large district association temples.

In May 1870, a dispute among members of the association quickly escalated into an armed melee, drawing in at least fifty Chinese combatants and spilling into the alleyway before police broke up the fighting. As a consequence, the meeting room was “torn to pieces,” while the guild’s icon, altar, and offering vessels, all “suffered considerably.”

As Ho and Bronson note, since laundry services were not a common occupation among men in China, there would have been no traditional patron deity for a washerman’s guild. The missionary Augustus W. Loomis, who took leadership of the Presbyterian Church in Chinatown in 1859, offers insight into this quandary. He notes that the washermen’s guild established altars to Guandi in order to secure prosperity for their businesses.

Ho and Bronson suggest that by 1887 a guild shrine may have been located at 810 Clay Street [#10].

5. Hang Far Low (Xinghua lou 杏花樓)

713 Dupont Street

See relevant comments in Additional Shrines in San Francisco’s Chinatown below.

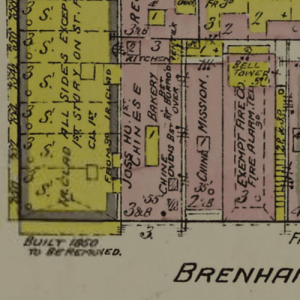

6. Ning Yung Association II (Ningyang huiguan 寧陽會館)

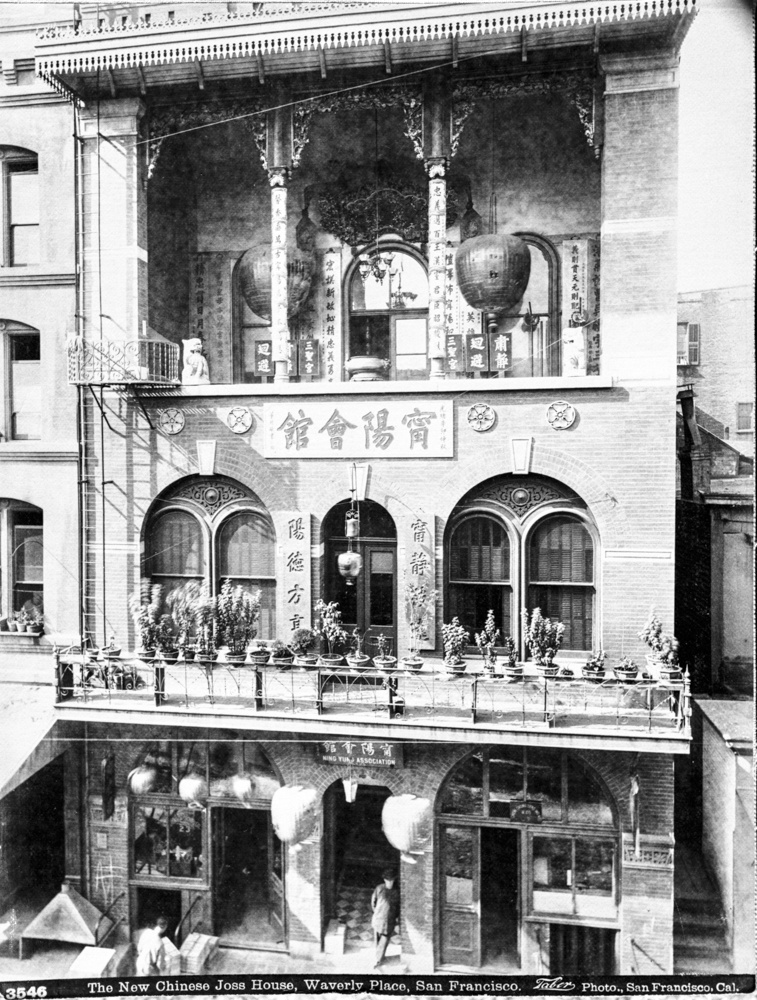

35 Waverly Place | 1905 Sanborn

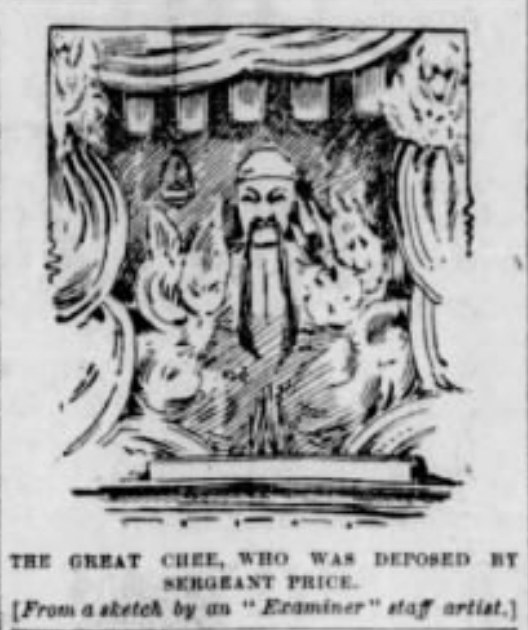

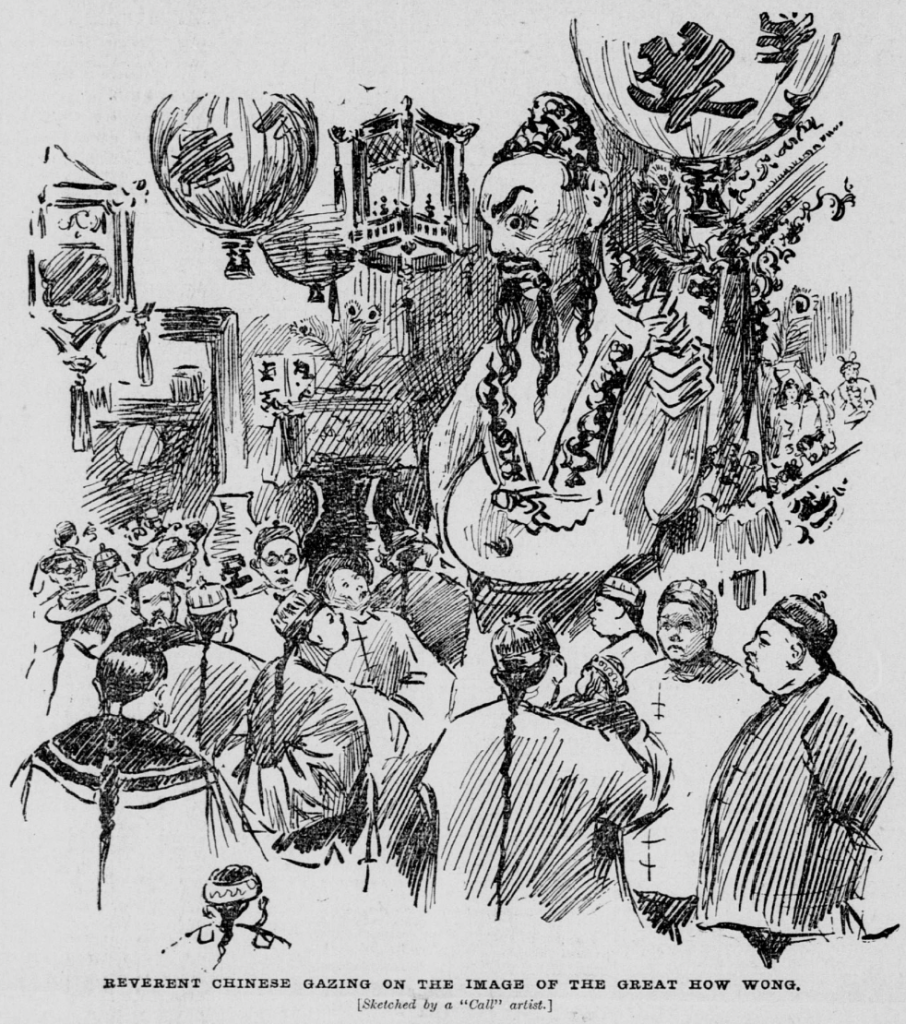

The Ning Yung Association moved from its original location [#45] to Waverly Place in 1891. Two rather crude newspaper sketches offer a glimpse of the official procession and parade as well as the new altar for the main Ning Yung Association icon, Guandi. The dangling hair queue added to the icon’s head was an attempt to highlight Guandi’s foreign origin rather than offer a faithful representation of its appearance. Moreover, rendering Guandi cross-legged, like a typical sitting buddha image, reflected more of the American popular perception of Chinese icons – what readers expected to see in Chinatown’s temples – than depict the icons that were actually enshrined.

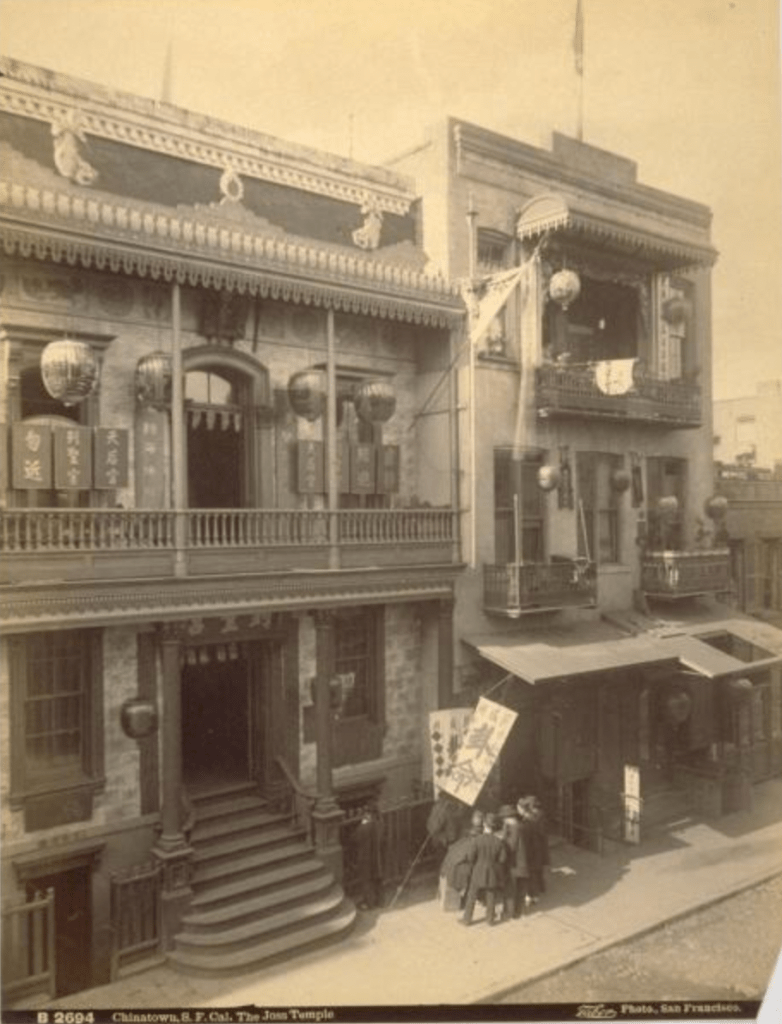

In 1892, Frederic Masters described Ning Yung’s building, located “on the west side of Waverly street between Clay and Sacramento streets,” as the finest temple in Chinatown and visitors reported marveling at its marble stairs and gas lighting. Construction costs reportedly reached $160,000 while the opening festivities, which lasted ten days, cost an additional $15,000 (newspaper reports, however, vary wildly on the final cost of construction and temple furnishings). Isaiah West Taber took a photo of the three-story building around 1891 (see below).

By the turn of the twentieth century, the company shrine hall emerged as one of the more popular attractions on the Chinatown walking tour circuit. One 1902 San Francisco Chronicle article provides a map, directions, and commentary for the most important sites to visit while in San Francisco’s Chinese district. The map suggests a prospective visitor start at Portsmouth Plaza and walk westward up Washington Street, making stops in Washington Place and Dupont Street before heading to Waverly Place. While walking south on Waverly tourists are instructed to visit the new Wong family temple [see #40] and the “Temple of the Great Joss,” describing it as the “most magnificent house of worship in the quarter” (the map mistakenly places the Ning Yung building north of Clay). According to the reporter, temple managers catered more to tourists than Chinese worshipers, “for the sake of American gold.”

After the 1906 earthquake, the association building was rebuilt, but the shrine hall was not replaced.

7. City God Temple I (Chenghua miao 城隍廟)

22 Waverly Place

8. Hong Sing Society

805 Clay Street [?]

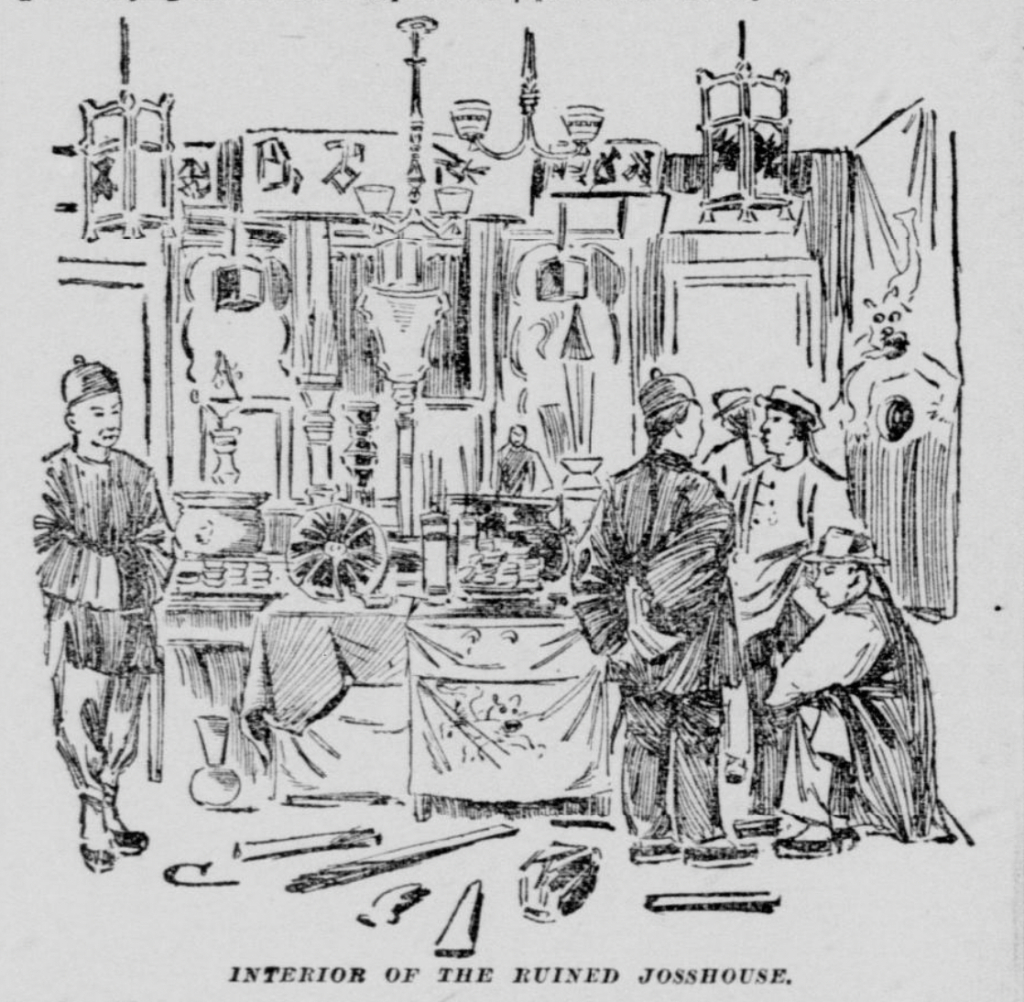

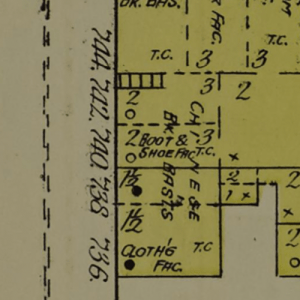

In 1892, a fire damaged the roof of the St. Francis Hotel, located on the southwest corner of Dupont and Clay (previously, I mis-identified this as the northwest corner), which consequently damaged a joss house belonging to the Hong Sing Society, reputed “on Waverly” (see below). There is no joss house located on the lower 800 Block of Clay Street on either the 1885 Supervisors’ map nor the 1887 Sanborn map, but the 1905 Sanborn map does indicate a joss house on the top floor of 805–807 Clay Street. Might this reflect the reestablishment of of a society shrine hall after the fire? There were dozens of Chinese secret societies formed in the 1880s and 1890s and I can find no further information on the Hong Sing Society. If the newspaper sketch is accurate, it shows that even obscure societies maintained fairly elaborate shrine halls.

9. Sze Yup Association II (Siba huiguan 四邑會館)

820 Clay Street

10. Dock Tin Society

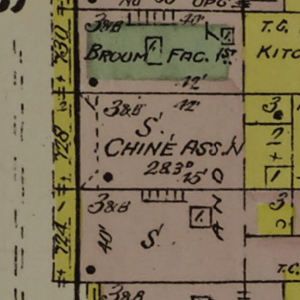

810 Clay | 1887 Sanborn

The 1887 Sanborn map notes this location at 810 Clay as “Chinese Laundry 2d Joss Ho 3d,” meaning it identified a joss house on the top floor. (The 1885 Supervisors’ Map identified the building as a restaurant.) Several contemporary photographs looking east down Clay towards Dupont (see proper map orientation here) suggest a shrine hall occupied the top floor (see below, also here, here, here & here). Hanging lanterns were a fixture on both restaurant and temple balconies, but one would expect to see inscribed boards above and on both sides of the main door of a temple. Existing photographs do not clearly show such details. Newspaper reports, however, provide some clues. In January 1895, continuing police raids in Chinatown claim to have captured a “war joss” (i.e. Guandi) from Dock Tin Society at 810 Clay [source]. If we turn to the 1905 Sanborn map we find the third floor was still being used for society rooms [here].

Regardless of these activities, 810 Clay was perhaps most known for its successful restaurant that operated on the first and second floors into the early twentieth century. It appears the restaurant or building owner rented space to various Chinese societies from time to time. Overall, the eye-catching balconies of 810 Clay would become a favorite of Chinatown photographers and postcard manufacturers (see detailed write-up by Doug Chan here)[additional photos of Clay and Waverly here].

11. Suey On Society (Ruiduan tang 瑞端堂)

34 Waverly Place

12. Tin How Temple (Tianhou miao 天后廟) & Hip Yee Society (Xieyi tang 協義堂) & Sam Yup Association II (Sanyi huiguan 三邑會館)[?]

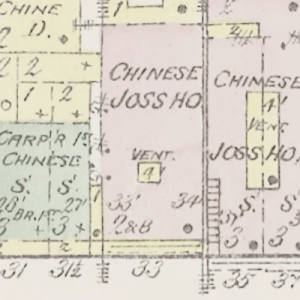

33 / 121 / 125 Waverly Place | 1887 Sanborn

In 1892, Frederic Masters published a survey of Chinatown temples in which he made two claims about the Tin How Temple on Waverly Place that have significantly shaped modern perceptions of the temple’s history. Masters, the head of the Methodist Chinese Mission in San Francisco, appeared to have deep personal familiarity with many of the temples he described, giving his assertions a sense of credibility that have been difficult to dislodge. When discussing Tin How Temple, Masters described it as “the oldest Joss-house in San Francisco,” claiming it had been “erected over forty years ago,” and explicitly identified it as “the property of the Sam Yap Company.”

As Ho and Bronson have recently argued, however, neither the claims regarding Tin How Temple’s age nor its affiliation with the Sam Yup Association are supported by historical documentation. Instead, they argue that the temple functioned independently, like several other contemporaneous Chinese American temples in San Francisco, and was at most only occasionally used by Sam Yup members. Moreover, Ho and Bronson find no evidence supporting a founding date earlier than the late 1870s.

Additional evidence supports Ho and Bronson’s conclusions. In 1868, nearly twenty years after the reputed founding date implied by Masters, the Sam Yup Association is documented as owning buildings on Clay and Sacramento Streets and leasing office space on Commercial Street, yet there is no mention of property ownership or tenancy on Waverly Place. Further, an 1880 city tax assessment locates a Sam Yup joss house at 825 Dupont Street [#15], suggesting no clear institutional connection to Tin How Temple, which is already documented as operating on Waverly Place by this time. Taken together, this evidence undermines the recurring claim, first proposed by Masters, that Tin How Temple was founded in the early 1850s, contemporaneous with the formation of the Sam Yup Association and, moreover, that it was used as the company’s original and primary joss house.

Notably, we can also add that between July 1872 and March 1873, the building at 33 Waverly – the same address associated with Tin How Temple prior to the 1906 earthquake – appeared repeatedly in city newspapers as a residential property available for lease [Fig 4]. There is nothing to suggest the space was being used as a temple at this time. In April 1874, public notice was given that the property had been leased for three years at $100 per month to an unnamed Chinese man [Fig. 5]. It remains unknown what role, if any, this individual played in transforming 33 Waverly into Tin How Temple, but the property was apparently sold before the lease agreement expired. As documented by Ho and Bronson, the building at 33 Waverly was sold in July 1876 by J. L. Eoff to a legal entity listed simply as “Tin How” for $15,000 [Fig. 6]. This transaction constitutes the earliest known documentary reference to what would become Tin How Temple. The property was sold again in 1879 to an otherwise unknown individual named Ly Haung, for the same price of $15,000.

New evidence suggests a critical role of the Hip Yee Society. As reported in the San Francisco Call, but not in the San Francisco Examiner, Ly Haung simultaneously purchased a second property in 1879 on Washington Place from the Hip Yee Society for $5,000. The timing of these two transactions is unlikely to be coincidental and suggests that the Hip Yee Society may have been conducting business under the name “Tin How,” purchasing the Waverly property in 1876 and selling it three years later bundled with the Washington Place property. The motivations behind these sales, as well as Ly Haung’s relationship to the Hip Yee Society, remain unknown.

Notably, both the Waverly and Washington Place properties remained in Ly Haung’s possession until December 1890, when he sold them back to the Hip Yee Society, which had earlier that year formally registered under the name Hip Yee Pioneer Association of California. Regardless of the formal ownership of 33 Waverly between 1879 and 1890, the Hip Yee Society was still described in 1883 as “owning” a joss house. Because this claim appears in a discussion of Chinatown’s largest and most prominent Chinese temples, it certainly refers to Tin How Temple, which otherwise goes unmentioned. This suggests, as already proposed by Ho and Bronson, that Ly Huang could have been a member of a temple committee designated to hold the deed, rather than an wholly independent investor.

Additional evidence underscores the role of the Hip Yee Society in Tin How Temple’s early history. The strongest evidence appears in the 1878 city directory which places the Hip Yee Society temple at 33 Waverly, two years after the property’s purchase by “Tin How” in 1876. The city directory from 1877, however, locates the Hip Yee Society temple at 730 Jackson Street. What may account for this discrepancy? Critically, the 730 Jackson Street address is claimed to have housed a temple dedicated to the goddess Tianhou around this period [#28], the same deity enshrined by Tin How Temple. Then in June 1877, we encounter newspaper reports of a new temple on Waverly, “constructed from a house,” dedicated to the “Daughter of Heaven,” an inexact rendering of the name Tin How (Tianhou) [Fig. 7].

On the basis of the above documentation, it is possible to reconstruct a tentative timeline of events. In the summer of 1876, a “Tin How” organization, likely functioning as the legal arm of the Hip Yee Society, purchased 33 Waverly Place. During the renovations required to convert the former residential building into meeting rooms and a shrine hall, Hip Yee members appear to have used 730 Jackson Street, a property owned by the prominent Chinese physician Li Po Tai, either as a temporary site for the Tianhou shrine or as the location of an already-operational temple established several years earlier. Once renovations at Waverly Place were completed, the icon was transferred to its new location in June 1877, at which point the Tin How Temple was formally dedicated and opened to the public. The involvement of the Hip Yee Society is confirmed by its listing at 33 Waverly Place in the 1878 city directory. For reasons that remain unclear, the Hip Yee Society, operating under the name “Tin How,” sold the property to Ly Haung in 1879. Ly Haung retained ownership of 33 Waverly Place for the following decade before selling it back to the reorganized Hip Yee Pioneer Association.

While further research is warranted, these records suggest that the Hip Yee Society played a consequential role in founding Tin How Temple in the late 1870s on Waverly and had a substantially closer relationship with the temple than the Sam Yup Association through at least 1890.

The reasoning for Master’s claim in 1892 regarding the affiliation between the Tin How Temple and the Sam Yup Association is uncertain. Perhaps the two entities had an informal, yet very close, relationship at this time. But even this claim is diminished when looking at contemporary newspaper reports. In 1892, the same year as Master’s survey of Chinatown’s temples, the San Francisco Examiner covered the birthday celebration of Tianhou. The reporter carefully notes that, “here in San Francisco, Tin How was remembered by but one society, the California Chinese Pioneer Association,” indicating the Hip Yee Pioneer Association – and never mentioning the Sam Yup Association. Master’s assertion that the Tin How Temple was “the oldest Joss-house in San Francisco,” being “erected over forty years ago” when the Sam Yup Association first formed cannot be taken as credible without new evidence. The identity of Ly Haung may prove important in partly explaining Master’s claim, especially if he was not connected to the Hip Yee Society, but a member of the Sam Yup Association, an organization comprised mainly of merchants who would been well suited to finance an expensive property purchase. Further research may resolve these questions.

As indicated by the temple’s name, the central icon enshrined was the goddess Tianhou 天后, the Empress of Heaven, also popularly known as Mazu 媽祖. The establishment of this figure on Waverly in 1877 must have been an important event for the Chinese in the city, as a San Francisco Call article in June of that year notes the Chinese were already calling Waverly Place, “Tin How Temple Street.” The importance of this goddess was already seen through the festivities held at An Ching’s Tin How Temple on Mason Street [#X3]. Before its destruction by fire in December 1874, this Mason Street temple appears to have been Chinatown’s most significant site associated with the goddess and its loss must have left a vacuum in the religious landscape of Chinatown. In time, this void was filled by the new Tin How Temple.

Isaiah West Taber took several photos of the original, pre-earthquake two-story building (with additional basement level) housing the Tin How Temple, including one in approximately the mid-1880s, as did Treu Ergeben Hecht (see below). This building’s facade was commonly used for early twentieth century Chinatown postcards (see here), helping to establish it as a visual icon of pre-1906 Chinatown. No objects belonging to the original shrine hall appear to have survived the 1906 earthquake and fire; I also know of no surviving illustrations or photos of the original altar (although one candidate shows an incense burner inscribed with Temple of Many Saints [liesheng gong 列聖宮] as seen on the signboard above the Tin How Temple doorway, see here [also here]; see an erroneous identification here).

Given the secondary name of the Tin How Temple as the Temple of Many Saints, we may surmise multiple icons were enshrined here, likely including Guanyin, but documentation is sparse as to the content of the shrine halls previous to 1906.

After the earthquake, the Hip Yee Pioneer Association sold the lot to the Sue Hing Benevolent Society who rebuilt building Tin How Temple. It was reconstructed on roughly the same footprint of the old building, renumbered now as 125 Waverly. San Francisco guidebooks highlighting walking tours of Chinatown after reconstruction would often highlight Tin How Temple as a main attraction, along with the newly rebuilt Kong Chow Association Temple. For example, the 1914 Chamber of Commerce Handbook for San Francisco cites both as “the leading Joss Houses in San Francisco,” adding that “owing to changing faiths and ideas, no more are likely to be built” [source].

13. Hip Sing Society (Xiesheng tang 協勝堂)

10½ Spofford Alley

14. Eastern Glory Temple II (Donghua miao 東華廟) & Gee Tuck Society (Zhide tang 至德堂) & Yee Fung Toy Society (Yufengcai tang 余風采堂)

35 Waverly Place | 1887 Sanborn

Adjacent to Tin How Temple, 35 Waverly was rebuilt as a three-story brick structure around 1885. Perhaps just prior, Li Po Tai appears to have moved his Eastern Glory Temple from St. Louis Alley [#22] to this address. An 1882 guidebook describing a temple “on Waverly Place” identifies the central icon as the Supreme Emperor of the Dark Heavens (Xuantian shangdi) and names other figures that were known to be enshrined at Li Po Tai’s St. Louis Alley location. (Ho and Bronson mistake the first edition of this work as being published in 1885.) A newspaper reporting on a murder in front of 35 Waverly in July 1886 definitively locates Eastern Glory Temple at this address.

There are at least two issues that deserve our attention regarding this timeline. For one, the 1883 San Francisco city directory still lists an unnamed joss house on St. Louis. I believe this refers to the Yan Wo Association’s shrine hall [#25], not the temple of Li Po Tai. The Yan Wo address on St. Louis is corroborated by a guidebook also published in 1883.

One another hand, a single newspaper account from 1885 reports the Eastern Glory Temple as occupying 730 Jackson Street, a building owned by Li Po Tai. Outside of being a mistake by the reporter, the 1885 Supervisors’ map identifies a structure at approximately 35–37 Waverly Place as a “new brick building, not finished.” If Li Po Tai was forced to temporarily relocate the Eastern Glory Temple during the reconstruction of the Waverly building, this may explain why the temple was described as being located on Jackson Street.

As detailed by Ho and Bronson, following the completion of the new building on Waverly Place, the second floor was occupied by the Gee Tuck Society shrine, which was destroyed by an explosion caused by rival saboteurs in 1888. Firemen responding to the resulting fire reportedly chopped Gee Tuck’s main icon into “toothpicks.” In 1904, the Gee Tuck Society acquired the building across the street at 134–140 Waverly.

We hear little of Li Po Tai’s top floor shrine hall through the late 1880s, but sanitation inspection sweeps in 1889 and 1890 target Eastern Glory Temple for its filth and disorder. Frederic Masters still names the Eastern Glory Temple at 35 Waverly in 1892 as does a Chinese language business directory from the same year. This was one year away from Li Po Tai’s passing in 1893 and thus it appears the regular upkeep of his temple had fallen by the wayside. At some point after Li’s death, the third floor was used by the Yee Fung Toy Society, who purchased the entire building in 1896.

Isaiah West Taber photographed 33 and 35 Waverly in the late 1880s (see below), offering a unique cityscape portrait for sale by 1889. It is possible to see hanging lanterns and signboards on both the second and third floors of 35 Waverly. Taber entitled the photo “The Joss Temple,” likely unaware he captured three different temples at the same time. Ho and Bronson date Taber’s photograph to the 1890s and assert the top floor is occupied by the Yee Fung Toy Society. Perhaps a closer inspection of the physical photograph (or higher resolution scan) can reveal identifying information on the temple’s signboards, but if this is the same photograph for sale as in Taber’s 1889 catalogue, the top floor of 35 Waverly could only be Li Po Tai’s Eastern Glory Temple.

A postcard published by Fritz Müller shows roughly the same perspective. Given there is no temple occupant on the second floor, we may infer this photograph was taken after the Gee Tuck Society relocated, but before the 1906 earthquake.

15. Sam Yup Association I (Sanyi huiguan 三邑會館)

825 Dupont | 1887 Sanborn

The Sam Yup Association is among the oldest district associations in San Francisco, founded in 1851 as the Canton Company, then operating as Sam Yup starting in 1853. Its close association with the Tin How Temple on Waverly at the turn of the twentieth century may explain why the latter is often cited as being founded in 1851, 1852, or 1853 (or sometimes, 1848). As noted above [#12], however, the affiliation between these two entities is onscure, but it is clear the Sam Yup Association did not found the Tin How Temple in the 1850s. In fact, there is no clear evidence of them operating a company shrine hall in San Francisco until the 1880s.

In 1868, Augustus Loomis described the Sam Yup Association as maintaining a “company house” on Clay Street above Powell Street. He did not indicate whether this structure contained a dedicated shrine hall. While it is reasonable to presume the presence of a small private altar, the Sam Yup headquarters did not appear to have a large public temple similar to other association temples. According to Ho and Bronson, the first Sam Yup temple in California was not in San Francisco, but in Sacramento in 1868.

In 1876 the Sam Yup Association was linked to an unknown address on Dupont Street and in 1878 is connected to 825 Dupont. The 1880 San Francisco city tax assessment listed a Sam Yup Company with a joss house at 825 Dupont (Ho and Bronson misread the address as 730 Jackson). The 825 Dupont address is corroborated by the city directory the following year in 1881, but unexpectedly also lists a “Sum Yup Co., Joss House” at 730 Jackson Street. This is the address of the poorly understood Jackson Street temple described as being devoted to Tianhou in the late 1870s [#28]. This is also the same address the Hip Yee Society occupied in 1877 before moving to 33 Waverly, the location of Tin How Temple, in 1878. The relationship between the Sam Yup Association, Hip Yee Society, and Tin How Temple through the 1880s is poorly understood.

The city directory of 1882 again locates the Sam Yup Association at 825 Dupont, but assigns no ownership to the joss house it lists at 730 Jackson; it is not clear if this building was still leased Sam Yup members, but the association is not again connected to this building in future directories. To add further complexity, the 1882 directory also lists an unnamed joss house on the west side of Waverly between Washington and Clay. This Waverly site was unlisted the previous year and could refer to the Tin How Temple, at 33 Waverly, or possibly Li Po Tai’s Eastern Glory Temple, at the top floor of 35 Waverly, which moved from St. Louis Alley around this time.

The city directory of 1883 again indicates the Sam Yup Association occupying 825 Dupont and an unnamed joss house at 730 Jackson. Moreover, the directory lists, for the first time by name, a Tin How Temple on Waverly, in addition to an unnamed joss house on the west side of Waverly, possibly the Eastern Glory Temple. There remains no evidence connecting the Sam Yup Association with the Tin How Temple up through 1883, as they appear as distinct organizational entities at this time.

The 1887 Sanborn map lists “Club Rooms & Joss Ho.” at 825 Dupont, suggesting Sam Yup members kept at least a private company shrine at this address through the 1880s. As suggested by Ho and Bronson, the Gee Tuck Society was identified in 1888 as an “offshoot” of the Sam Yup Association, thus they may have shared the shrine hall on the second floor of 35 Waverly.

Fundraising efforts in 1899 finally allowed the Sam Yup Association to open their own dedicated public temple the following year at 929 Dupont Street [#24], as is reflected in the 1905 Sanborn map [here]. The main icon enshrined was Guandi.

16. Chee Kong Society (Zhigong tang 致公堂)

69 / 32 Spofford Alley | 1887 Sanborn

Often cited as the most wealthy and influential of all Chinese secret societies, the Chee Kong Society occupied a three-story building on Spofford since 1881, moving from 827 Washington Street. Later to be known as the Chinese Freemasons, the Chee Kong Society was politically oriented and devoted, at the time, to the overthrow of the Qing emperor. In other many regards, they were similar to other Chinese communal organizations looking to help its members prosper in the United States. According to Ho and Bronson, the Chee Kong Society continued observing similar rituals as their parent organization in China, the Heaven and Earth Society (Taindi hui 天地會). As tensions grew in San Francisco’s Chinatown due to legal, social, and economic deprivations in the 1880s and 1890s, the American public developed a lurid fascination for information about Chinatown’s “hatchet men” and their “tong wars.” The Chee Kong emerged in public consciousness as one of groups who most profited from violence and vice and in 1886 Harper’s Weekly covered the the society’s elaborate initiation rituals which took place before a religious altar. The shrine hall is not described in the text and the accompanying sketch may be fictional (see below).

After the Geary Act of 1892 extended the federal laws regarding Chinese exclusion and started requiring Chinese registration, the flames of violence were fanned, triggering a series of police raids on prominent “highbinder” headquarters and joss houses through the 1890s. This coincided with the popularization of newspaper sketch artists who often had great latitude in depicting events covered in their newspapers. In 1893, one artist dramatically amplified the violence and terror associated with Chee Kong and other secret society initiation rituals, transforming them into caricatured spectacles (see below).

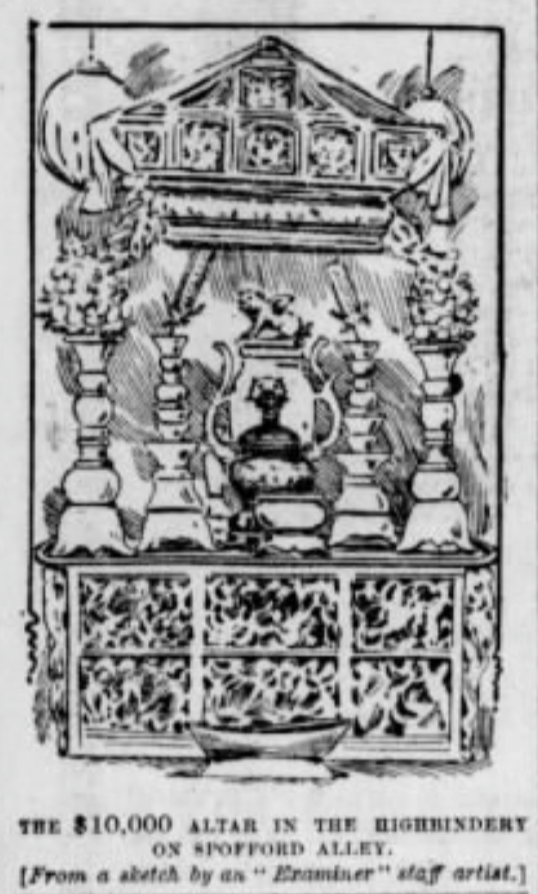

If we turn away from the depiction of initiation rituals, there is very little remaining visual documentation of the Chee Kong shrine hall on Spofford before the earthquake. While two images we do possess are hasty newspaper sketches, they capture an interesting issue of legal jurisprudence concerning Chinese American religious material artifacts. After a series of police raids around Chinese New Year in 1891, newspaper reports claim Chee Kong’s main icon, Guandi, and smaller images of his two attendants Guan Ping 關平 and Zhou Cang 周倉, including other ritual artifacts, were targeted and damaged by the police. The Chee Kong organization sought legal restitution from the city and police chief in the form of $1,227. A sketch artist for the Examiner submitted two drawings of the Chee Kong altar, which was estimated to have cost $10,000, presumably before the police took axes to the shrine hall (see below).

After 1906, the Chee Kong Society rebuilt on the footprint of their old building, complete with new shrine hall.

17. Wong Kong Ha Shrine II (Huang jiangxia 黃江夏)

137 Waverly Street

18. Guanyin Temple (Guanyin miao 觀音廟)

60 Spofford Alley | 1887 Sanborn

Opened by the early 1880s, the Guanyin Temple was located on the top floor of a three-story brick building on the southwest corner of Spofford Alley and Washington Street. The temple is curiously missing form both the 1885 Supervisors’ map and the 1887 Sanborn map. Nevertheless, in 1883, a Guanyin shrine is cited as located on the “contracted upper floor of a small building on Washington.” Frederic Masters, writing in 1892, notes the shrine hall was atop a “dingy staircase” that held a “rudely carved image and grimy vestments.” According to Masters, the space held an assortment of other figures, including the God of Medicine (Huatuo 華佗), the Grand Duke of Peace (Suijing Bo 绥靖伯), and Tsai Tin Tai Shing (Qitian dasheng 齊天大聖, otherwise known as the Monkey King, Sun Wukong 孙悟空).

Despite the popularity of Guanyin among Chinatown’s residents, we know very little about the rituals and ceremonies that took place at this small temple. Among what we do know is that sometime in the early 1880s, during the three-day birthday celebrations of Guanyin, a feast was held in her honor, inclusive of meat which seemed to surprise some onlooking Chinese, and her icon was paraded around Chinatown, leading to its installation in a Chinese theater where a performance was held in her honor. When the performance was finished in the early morning, her icon was returned to its altar on Spofford among a clamor of cymbals and cheers.

In a rare discovery, a brochure seeking funds to restore the temple has survived, dated to 1886 (guangxu 12). As discussed by Ho and Bronson, the brochure claims the temple had existed for more than thirty years at that point. It also notes the space was managed by Li Xiyi 李希意. The success of this fundraising endeavor is unknown, but the building at 60 Spofford seems to have remained in poor condition, being recommended for condemnation by the city health inspector in 1890 (city property records in 1886 cite an otherwise unknown Liebermann as the building’s owner). Regardless, the temple seems to have remained untouched as Masters attests to its divinely crowded quarters two years later. The temple also seems to have issued a weekly eight-page newsletter or newspaper in 1893, called Bun Ding, which was printed on “bright red paper and partly colored ink.” Ho and Bronson attest to the poetic writing of the fundraising brochure, speculating it could have been penned by Li Xiyi himself. Is it possible he also wrote or edited a regular weekly publication? The 1905 telephone directly still records a “Quon Yum Temple” at 60 Spofford, next to a printer.

There is very little visual record of Chinatown’s “Quon Yum Temple.” Isaiah West Taber took a photo looking north down Spofford and the temple’s round lanterns can barely be seen at the far end. Additionally, Arnold Genthe took at least one photo showing the exterior signage of this temple between 1896 and 1906 (see both below). The temple was apparently not rebuilt after 1906.

19. Kai Sen Shea Society (Jishanshe tang 繼善社堂)

819½ Washington Street

20. Bing Kong Society I (Binggong tang 秉公堂)

817 Washington Street

21. Grand Chinese Theater

814 Washington Street

See relevant comments in Additional Shrines in San Francisco’s Chinatown below.

22. Eastern Glory Temple I (Donghua miao 東華廟) Update August 2025: Confirm St. Louis location

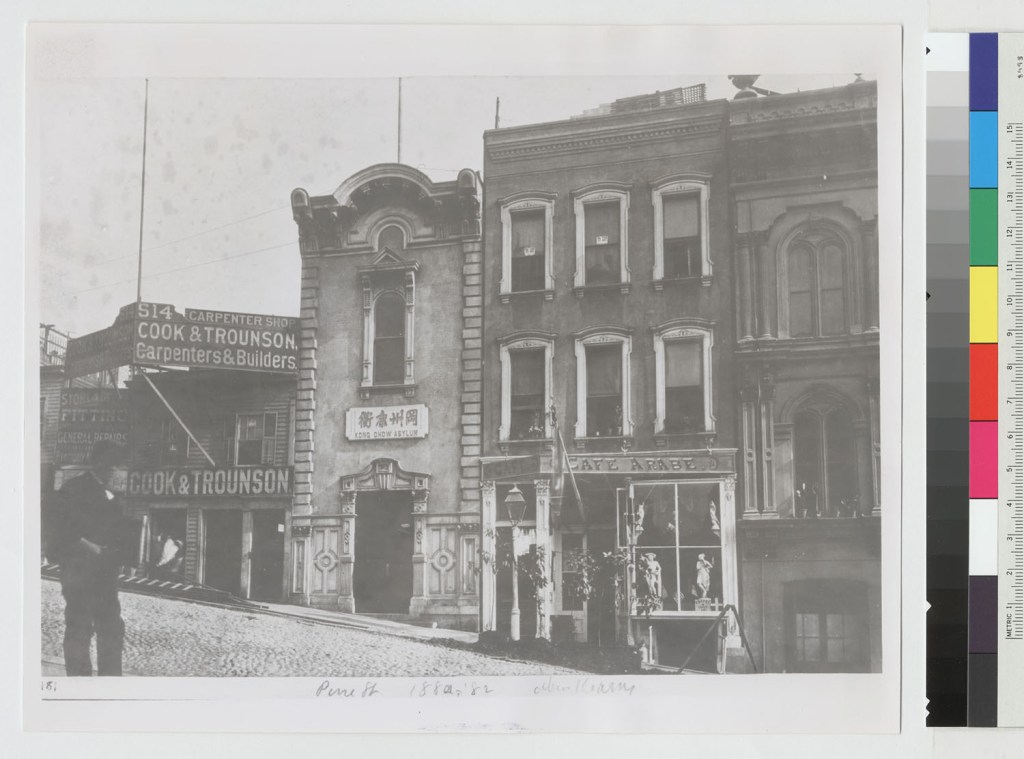

St. Louis Alley | 1887 Sanborn

Famed Chinatown physician Li Po Tai (Li Putai 黎普泰) started this privately owned temple in 1871 after narrowly surviving a gas explosion the previous year that left him severely scarred and reputedly claimed the life of a friend. The multi-room temple, known as Eastern Glory Temple (Donghua miao 東華廟), was on the third floor of a large building on St. Louis Alley, allowing entrance from both Dupont and Jackson streets. A city directory from 1877 lists the address as 921 1/2 Dupont, which refers to a narrow alley running west off Dupont. The precise location along St. Louis, a tight alleyway named by the local Chinese as “Conflagration Alley” (Huoshao xiang 火燒巷) as early as 1877, has been difficult to determine. A map of Chinatown compiled by Henry Josiah West in 1873 placed a joss house at the 90-degree bend in St. Louis Alley [here]. Until recently, I considered this in error and Ho and Bronson’s published work also considers this inaccurate, instead placing Li Po Tai’s temple at the far rear of a building fronting Dupont Street and labelled a joss house on the 1887 Sanborn map.

The recent discovery of an oil painting by Karl Wilhelm Hahn (1829–1887) corroborates West’s placement, however. Hahn depicts St. Louis Alley looking south and shows a temple doorway on the third story of a building (see below). Rather uncharacteristically, the horizontal Chinese signboard is clearly legible, saying “Eastern Glory Temple.” Even the vertical pillar boards (yinglian 楹聯) appear to match mostly match with known textual records (and a partly obscured photograph). According to the numbering on the 1887 Sanborn map, this doorway is approximately equivalent to 4 or 5 St. Louis Alley. The Bancroft Library currently dates the painting to 1885, but we can now see Hahn’s work formed the basis for an engraving published in The Pacific Tourist, a guidebook first released in 1876 and reprinted in 1881 (see below).

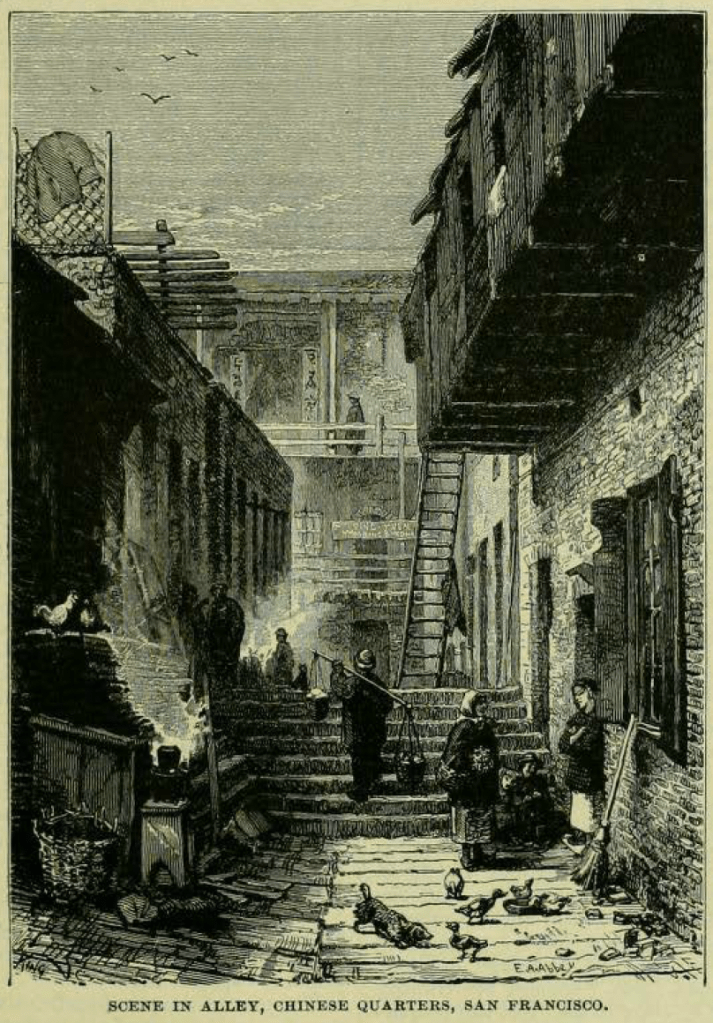

Moreover, a rarely consulted report from 1873 describing the conditions of Chinatown clarifies Eastern Glory Temple occupied the entirety of the third flood of the building, spanning six rooms (an earlier Daily Alta account in 1871 noted eight rooms in total). If we consult the 1887 Sanborn map, the temple occupied a building abutting the rear of the Grand Chinese Theater, covering multiple ground-floor addresses, from 1 to 7 St. Louis Alley. The first room, furthest east, was fitted with a small door and led to a reception area while the second room sold ritual supplies such as candles and paper money. The other rooms enshrined icons. A larger second doorway toward the western end of the building, seen in Hahn’s painting, led directly to the main altar and was considered the main temple entrance.

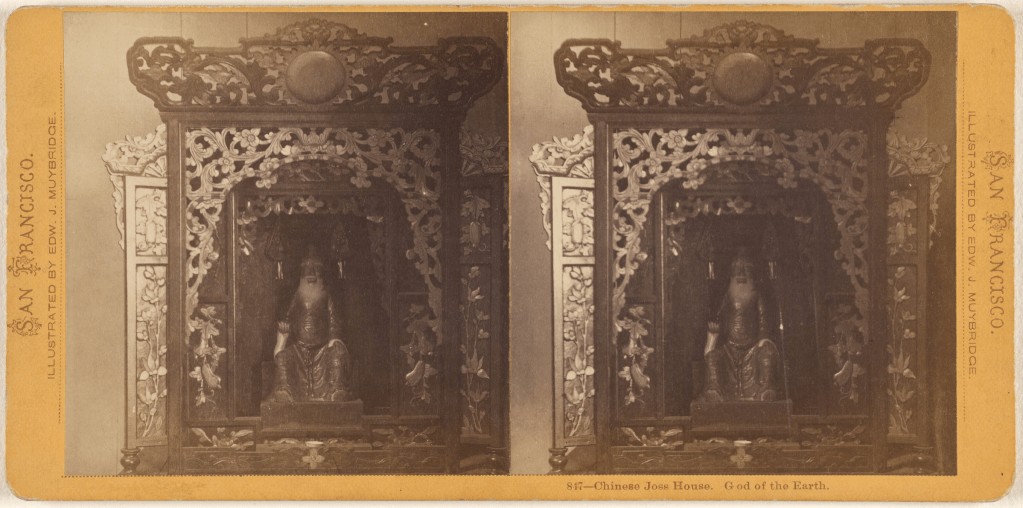

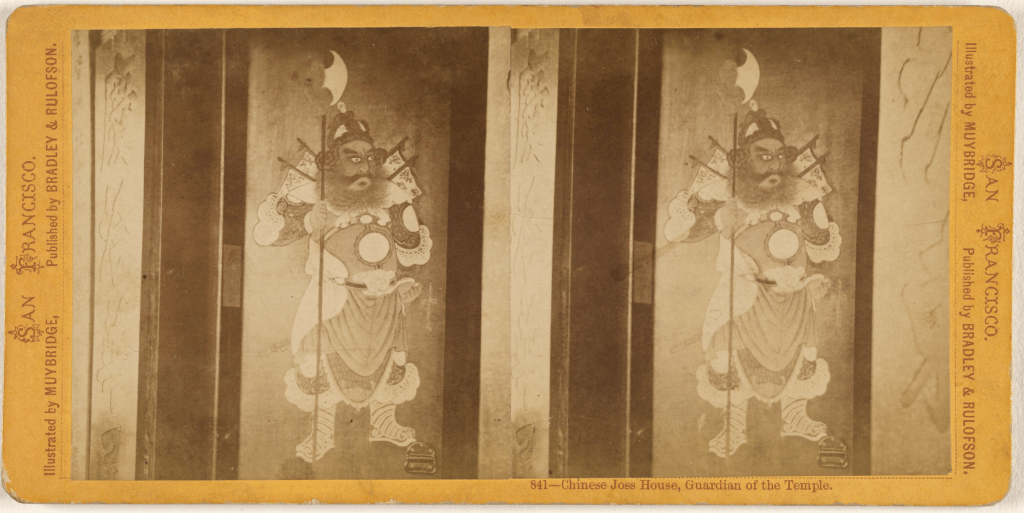

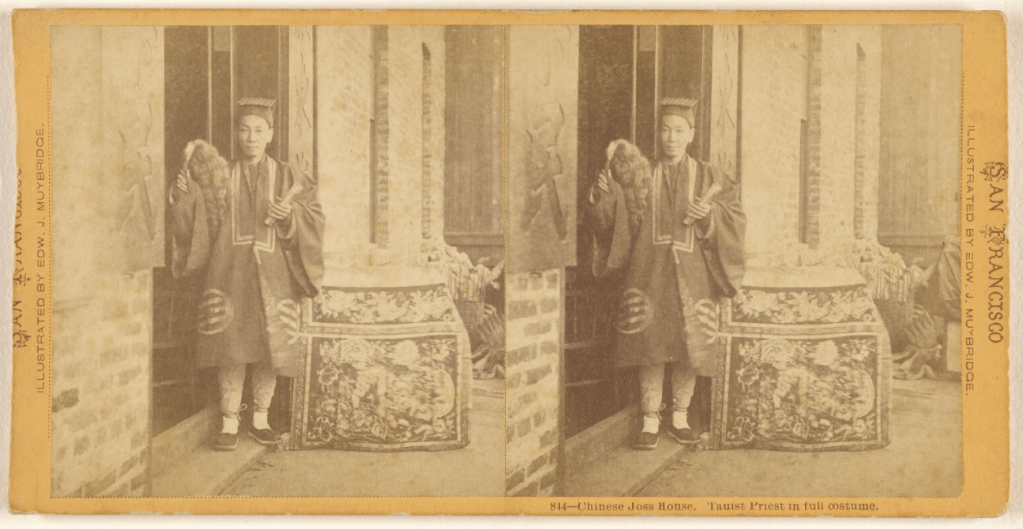

A series of stereo-photographs taken by Eadweard Muybridge offer clear, rare depictions of the temple interior, including the main altar (see below). The Supreme Ruler of the Somber Heavens (Xuantian shangdi 玄天上帝; also Northern Emperor [Beidi 北帝]) sits in the center. Some contemporary reports given by visitors seem to conflate this central icon with Buddhist figures. It also appears Li may have moved icons around as one visitor claims in 1876, and another in 1880, that Guandi was the central icon, but this may just be a mis-identification (also see next entry for Yan Wo). In the Muybridge photo of the main altar, the Northern Emperor is flanked by Guandi to his left and righteous official Hong Sheng 洪聖 to his right.

The main hall originally enshrined a total of six icons, while other deities were found in adjoining rooms. Notably, Tianhou and Lady Golden Flower were reported enshrined in a room to the left of the main hall while Guanyin was enshrined in a room to the right. One visitor writing in 1890, but describing experiences more than a decade earlier, noted a Chinese liturgy to Guanyin imprinted with her image was available for sale. This was likely similar to the printed Guanyin liturgy dispensed at Ah Ching’s Tin How Temple [#X3], which was still in operation through late 1874. All of the original icons were reportedly made of local clay, a necessity after an intermediary who went to China with $3000 to purchase ritual supplies had disappeared. The temple’s icons were molded, painted, and decorated by Chinese immigrants in San Francisco. The craftsmen may have also made extra copies. One tourist recounting her visit to Eastern Glory Temple in 1877 noted the presence of miniature versions of the icons, claiming they were “possibly for sale.”

During a period when district association temples comprised a single room with a singular central icon, such as reflected at Kong Chow temple [#X2] and Ning Yung temple [#45], the multi-room temple complex of Li Po Tai displaying approximately a dozen icons must have stood out as an exceptional departure from prevailing norms. Only Ah Ching’s privately owned temple at the time held such a wide assortment of figures, but his temple was located further from the heart of Chinese life and tourist attention. Unsurprisingly, after its opening in the early 1870s, Eastern Glory Temple was known as the “boss temple” and “Grand Temple” of Chinatown. Some early reports, likely floated by those unhappy with the growing Chinese religious presence, inflated the grandeur of Li’s temple, claiming it possessed “over a hundred gods,” with “more expected on the next China steamer.”

By 1880, at least three major Chinatown celebrations centered upon Eastern Glory Temple, including the birthdays of the Northern Emperor (3rd day of 3rd lunar month) and the God of Wealth (16th day of 7th lunar month), as well as the summertime Ghost Festival, suggesting this privately-run temple was a major center of local religious life through the 1870s.

At least two detailed engravings were published in the 1870s showing the interior of the main shrine hall with three total altars (see below). The importance of this temple for the religious landscape of Chinatown was only further heightened by the prominence of Li Po Tai, a successful doctor who ran his business near Portsmouth Square and who was considered the wealthiest among all Chinese residents. Yet, the importance of Eastern Glory Temple was often diminished by tourists due to its location in a small, dark alleyway with “rickety stairs.” The claustrophobia of the alley, as well as the clamor of local gambling halls and brothels, caused many tourists to recount their visit to one of Chinatown’s main joss houses with a mixture of fascination and unease.

Sometime around 1882, Li Po Tai seems to have moved the contents of his Eastern Glory Temple to 35 Waverly [#14], next door to Tin How Temple [#12]. Frederick Masters still notes an Eastern Glory at 35 Waverly in 1892, but does not afford it a description, suggesting it had fallen from previous heights as a major Chinatown attraction.

Li passed on March 20, 1893 soon after turning 76. In July of that same year, one of his properties in Chinatown succumb to fire, but this was not his old temple site on St. Louis Alley as suggested by Ho and Bronson; Li never owned this building. Municipal property records from 1886 and 1894 show Li, or his estate, owning buildings at 730 Jackson and 1010/1012 Dupont. This is confirmed by contemporary newspapers covering his estate which variously estimated the value of his properties between $50,000 and $300,000 dollars. The building lost to fire in July 1893 was at 730 Jackson, which Li leased to at least two other groups that operated joss houses from that address in the mid-to-late 1870s and early 1880s.

23. City God Temple II (Chenghua miao 城隍廟)

1018 Stockton Street

24. Sam Yup Association III (Sanyi huiguan 三邑會館)

929 Dupont Street

25. Yan Wo Association (Renhe huiguan 和會館)

5 St. Louis Alley & 933 Dupont Street | 1887 Sanborn

In 1877, the Yan Wo organization was reported to be the only district association among the major six that had not yet established a company temple. By 1880, however, a San Francisco city tax assessment records the Yan Wo Association as operating a joss house at 5 St. Louis Alley. This claim is corroborated by an 1883 Chinatown guidebook, which also locates a Yan Wo temple on St. Louis Alley. Consequently, it may be the case that an unnamed joss house listed on St. Louis Alley in the 1883 city directory refers to this same district association temple. To date, however, I have found no descriptive accounts of Yan Wo’s shrine hall off this alleyway.

There are still questions that remain outstanding. We now know that Eastern Glory Temple occupied the top floor of 5 St. Louis Alley until approximately 1882. If we take the 1880 city tax assessment at face value, the Yan Wo joss house may have shared the space or occupied a different floor of the same building. Moreover, if the 1876 and 1880 visitors’ reports claiming Guandi was the the central icon in Eastern Glory Temple are correct (they may not be, however, see previous entry) – thus, displacing the icon of the Northern Emperor – this may indicate an critical change of stewardship to Yan Wo as early as 1876, but this remains uncorroborated and speculative. The extant evidence does not allow us to create a clear timeline of events.

By 1892, the address of the Yan Wo Association had moved around the block to 933 Dupont Street, where its shrine was outfitted with an icon of Guandi and “fitted up in elegant style. The 1887 Sanborn map locates a joss house at the rear of the 933 Dupont building, possibly pointing to a move at least five years earlier.

26. St. George Temple

731 Jackson Street

The 1875 Bishop San Francisco City Directory contains a curious entry: St. George Joss House, 731 Jackson [source]. It is listed again in the 1876 edition [source], but is missing the following year. Nothing is known about this temple. It is not clear why the Christian martyr, St. George, famed for his defeat of a villainous dragon, is adopted as the name of a Chinese temple, but Frederick Masters provides a clue. In his survey of Chinatown temples in 1892, Masters describes Guandi as the “Saint George of Far Cathy,” drawing attention to the militaristic aspects of both figures. The St. George Joss House may have been one of many Chinese temples devoted to the semi-historical figure Guandi.

27. Bing Kong Society II (binggong tang 秉公堂)

740 Jackson | 1887 Sanborn

After a series of violent altercations with the Chee Kong Society, the organization from which the Bing Kong Society had originally split, and amid rising tensions in Chinatown more broadly, city police undertook a coordinated raid of Chinese secret society headquarters just prior to Chinese New Year in 1891. The Bing Kong Society was targeted first. When officers entered its headquarters at 817 Washington Street, at the corner of Waverly Place [#20], the interior was ransacked as “joss and idols fell with a crash” [source].

In the autumn of the following year, the society converted a former storefront at 740 Jackson Street into a shrine hall for the veneration of its ancestors. Local newspapers covered the dedication ceremony and included a small sketch illustration of the event (see below). Major ritual occasions from this period—categorized by Ho and Bronson as dajiao 打醮—featured large, wood-framed paper effigies of deities positioned at the temple entrance. These temporary figures were ritually burned at the conclusion of the festivities.

For comparison, I have also included a painting by Theodore Wores depicting similar figures at an unidentified Chinatown temple. The original painting was likely destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire (for additional depictions, seen here & here). Because large festivals attracted many non-Chinese visitors, contemporary observers sometimes mistakenly assumed that these monumental images were permanent fixtures of Chinese temples. By the late 1890s, the Bing Kong Society had established new headquarters and a shrine hall at 34 Waverly Place [#12].

28. Jackson Street Temple

730 Jackson Street | 1887 Sanborn

One temple on Jackson Street, often described as located between Dupont and Stockton Streets, remains obscure. It’s important to note that Jackson Street, especially the stretch between Stockton and Dupont streets, was perceived as the heart of old Chinatown, thus a passing tourist reference to a “joss house on Jackson” might have been intended to be more evocative of Chinatown’s religious difference than descriptive of a real location. This notwithstanding, there have been an handful of specific claims about this site as a temple that deserve out attention.

Most importantly, an 1876 guidebook identifies a site on Jackson as a temple dedicated to the goddess Tianhou (Mazu), a claim repeated in 1880 and again in 1882 (the latter account deriving from a visit to Chinatown in the summer of 1878). The 1876 description places the Tianhou temple “on the north side of Jackson, near Stockton,” a location consistent with 730 Jackson Street.

In 1883, however, another guidebook identifies a temple “on Jackson Street near Stockton” as the Eastern Glory Temple. This may reflect confusion with Li Po Tai’s earlier location on St. Louis Alley [#22], which was sometimes also described as being off Jackson Street. It is also possible Li temporarily relocated to Jackson Street sometime around 1883 or 1885. Evidence suggests that Li moved his Eastern Glory Temple from St. Louis Alley to 35 Waverly as early as 1882 [#14], but construction at this Waverly address may have forced his temporary relocation in the mid-1880s.

Complicating matters further, Li owned the building at 730 Jackson, as property records in 1886 and 1894 attest (a record of a fire further confirms he owned the building as early as 1874). The 1886 assessment records that Li owned – or, leased to tenants who operated – two joss houses, five opium dens, and two stores along Duncomb Alley. This description aligns closely with the 1885 Supervisors’ map, which depicts the two-story structure at 730 Jackson as subdivided into ten apartments with two joss houses and five “opium resorts” among them. I have found no evidence that two distinct joss houses operated simultaneously at this address. These spaces may have functioned as separate shrine halls or chapels for the same joss house, similar to the arrangement documented at the Eastern Glory Temple on St. Louis Alley.

At least two different groups used the Jackson Street site as a shrine hall at separate times. The 1881 city directory lists a “Sum Yup” joss house at 730 Jackson Street, referring to the Sam Yup Association later loosely affiliated with the Tin How Temple on Waverly [#12]. If city records are accurate, it is reasonable to infer that the Sam Yup Association leased this space from Li Po Tai. In 1882, the city directory simply lists the address as an unnamed joss house.

Several years earlier, in 1877, a different group known as the Hip Yee Society was also reported as maintaining a temple at 730 Jackson. Notably, in the following year, the Hip Yee Society is listed at 33 Waverly, the site of the famed Tin How Temple and a building the society ultimately (re)acquired in 1890. It could be the case that the 1876 city guidebook citing a Jackson Street Tianhou temple was referring to the same Hip Yee Society temple. The precise relationship between the Tianhou temples on Jackson and Waverly remains unclear, though the Hip Yee Society may have been a key link between the two.

There was at least one moment when the Jackson Street temple appears to have commanded citywide attention. In a work published in 1880, Chinatown’s birthday celebrations for Tianhou (the twenty-third day of the third lunar month) are described as taking place at the Jackson Street temple, suggesting that it was regarded at the time as a particularly important shrine to the goddess. Earlier celebrations in 1873 and 1874 had been held at Ah Ching’s Tianhou temple on Mason [#X3]. It is uncler if the Jackson temple in 1880 was managed by Hip Yee, Sam Yap, or another organization or individual. It does appear, however, the subsequent rise in prominence of the Waverly temple through the 1880s may be closely linked to the disappearance of the Tianhou temples on Mason and Jackson.

In 1885, Li Po Tai’s Eastern Glory Temple is described at occupying 730 Jackson (a variant account claims it was the How Wong Temple of the Yeong Wo Association [see #35]). If accurate, this would corroborate the hypothesis of Li’s temporary relocation during the mid-1880s. It may also explain why the 1885 Supervisors’ map marks a joss house at this location, while the 1887 Sanborn map does not. John Hittel’s San Francisco guidebook map, published in 1888, also shows a joss house at approximately 730 Jackson, but this map seems to uncritically copy most of the joss house locations identified by the 1885 Supervisors’ map. Frederick Masters does not mention a Tianhou temple, or any other religious site, on Jackson in his comprehensive survey of Chinatown temples in 1892.

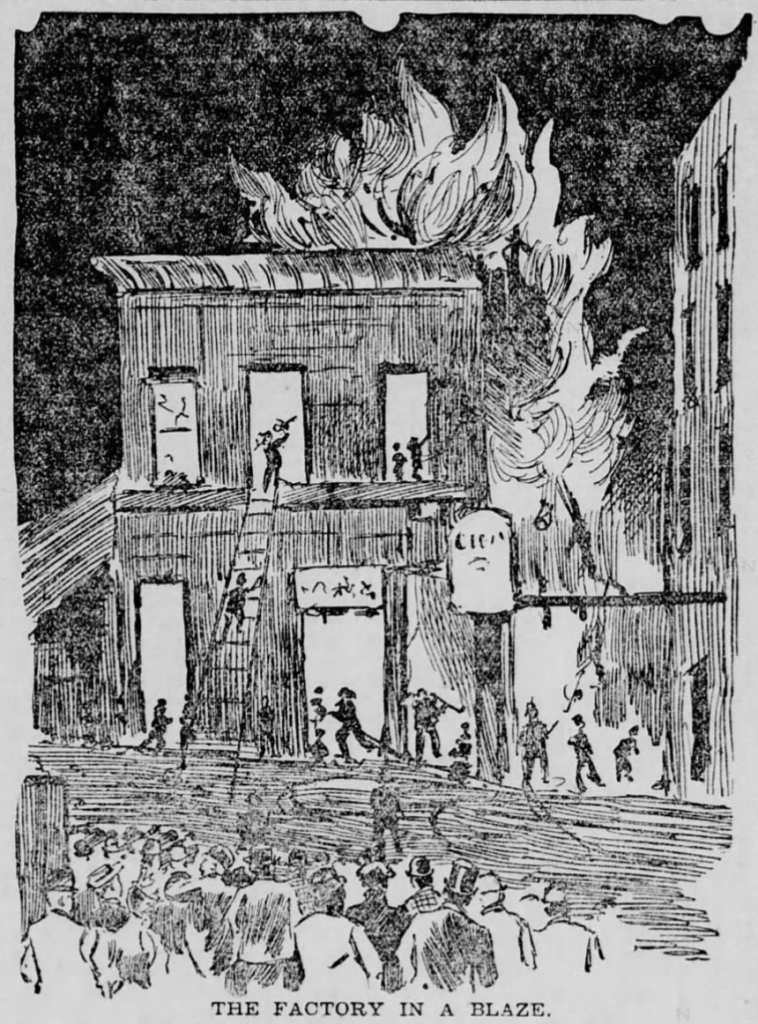

In July 1893, only months after Li Po Tai’s death, a fire broke out at 730 Jackson Street (misreported in newspapers as 830 Jackson), displacing a tinsmith, a cigar maker, and numerous tenants living in the rear of the long structure (see below). One newspaper account remarked that “the building was one time a joss-house of a powerful society,” a vague characterization that obscures the site’s complex – and rather significant – religious history.

29. Yuen Fong Restaurant

710 Jackson Street

See relevant comments in Additional Shrines in San Francisco’s Chinatown below.

30. Voorman’s building shrine

Sullivan’s Alley

See relevant comments in Additional Shrines in San Francisco’s Chinatown below.

31. Sullivan’s building shrine

Sullivan’s Alley

See relevant comments in Additional Shrines in San Francisco’s Chinatown below.

32. Hop Sing Society (Hesheng tang 合勝堂)

1025 Dupont Street

33. On Yick Society (Anyi tang 安益堂)

726½ Pacific Street

34. Chinese Merchant’s Exchange Shrine

739 Sacremento Street

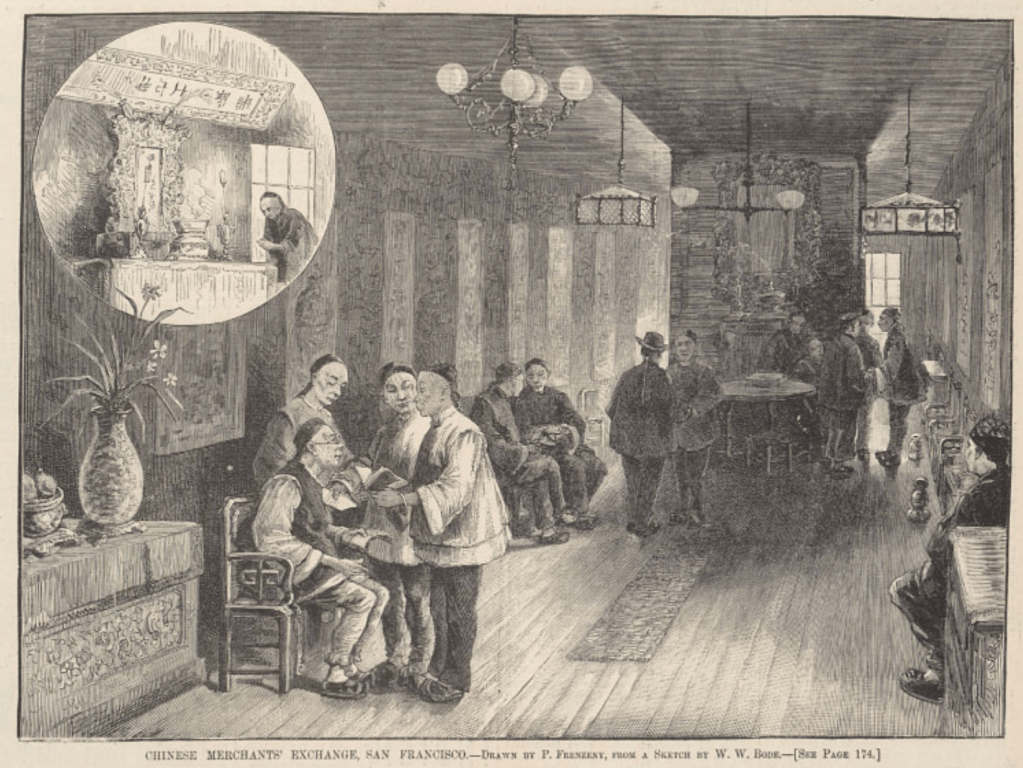

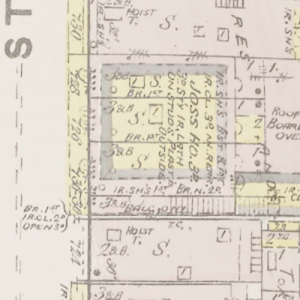

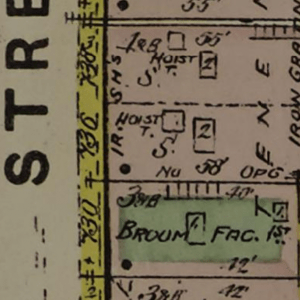

By as early as 1854, the Chinese had started building a merchants’ exchange [source]. By 1882, the Chinese Merchants’ Exchange had moved to 739 Sacremento Street and operated independently of the district associations, yet wielded considerable influence within Chinatown. Contemporary accounts note that the Exchange building contained a joss shrine, before which business transactions were formally concluded. This small shrine, centered on a spirit tablet, was reproduced as an inset illustration in Harper’s Weekly in 1882 (see below).

35. Yeong Wo Association II (Yanghe huiguan 陽和會館)

730 Sacramento Street | 1887 Sanborn

The Yeong Wo Association was formed in 1852 by a small group of early Chinese immigrants, among whom Norman Assing (b. 1808, born Yuan Sheng 袁生) emerged as the most prominent. An English-speaking naturalized citizen, Assing first arrived in the United States in 1820 and, after returning to China, came to California in July 1849, where he opened a successful restaurant. In 1851, Assing played a central role in organizing San Francisco’s first Chinese New Year celebration, hosting a large feast at his home and inviting members of the city’s police force. In subsequent years, this event developed into one of the most visible expressions of Chinese identity and communal celebration in the city.

The Yeong Wo Association is known to have maintained a temple on the southwestern slope of Telegraph Hill by at least late 1852. We can now connect this site to an earlier unnamed “idol temple” noted in newspapers across the US in 1851 as being erected at an undocumented location in San Francisco [#X1]. The temple was built in the summer of 1851, reputedly based on a “modified Chinese plan” with imported Chinese spruce timber. The formal dedication of the shrine hall in 1852 was captured with unusual detail by a local newspaper reporter. As analyzed by Ho and Bronson, the dedication of the shrine hall included Chinese opera performances as part of the festivities. The reporter mistakenly interpreted these theatrical performances as ritual actions conducted by Chinese priests. The temple’s icon was described only as resembling “a little doll,” with no further detail provided.

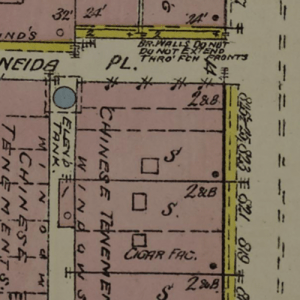

By 1868, the Yeong Wo organization headquarters was still in the “old house” on Telegraph Hill, but was developing property on Sacramento Street – addresses at 727 and 730 Sacramento Street appear in city directories of the 1870s and early 1880s. At an unknown time, religious activities seem to have shifted to a temporary location on Brooklyn Place [#2]. By September 1879, newspapers reported on Yeong Wo’s birthday festivities on Brooklyn Place honoring Houwang 侯王, a semi-historical figure who had become the association’s “patron deity.” Matters are complicated by the presence of a Houwang Temple on Brooklyn Place dating back to at least 1866, which appears to have been loosely affiliated with the Yeong Wo Association. Ho and Bronson speculate this earlier temple belonged to a benevolent society connected to Yeong Wo. Regardless, Houwang became so closely associated with this area of Chinatown that by the summer of 1877 residents referred to Brooklyn Place as “How Wong Temple Street.”

The Yeong Wo Association’s devotion to Houwang stems from the fact that all of its members hailed from Xiangshan 香山 district (modern Zhongshan), a region that contained an important Houwang temple. The physical icon of Houwang in San Francisco was reputed to have an especially distinctive provenance. According to one tradition retold by the San Francisco Examiner, it was discovered in Xiangshan “centuries ago” after a devastating flood receded, revealing the small figure atop a mountain; the deity thereafter ensured peace and stability in the region. When the icon was brought to California, it was said to have first resided in apartments on Mason Street near Post Street. Notably, this intersection is precisely where Ah Ching would establish his Tin How Temple [#X3], possibly as early as 1856, suggesting this area may have served as an important hub of Chinese religious activity shortly after large-scale immigration began.

The placement and potential movement of Yeong Wo / How Wong Temples until the late 1880s remains difficult to reconstruct. An 1880 city tax assessment claims that Yeong Wo maintained a company house and joss house at 730 Sacramento Street, but this most likely refers to a small altar, not a full shrine hall. In 1883, for example, the festive parade for Houwang’s birthday still originated at Brooklyn Place. Parade members traversed down Sacramento, up Commercial, and along Dupont until arriving at the Chinese theater on Jackson Street where performances were held for the occasion. There is also no mention of returning to Sacramento street at the end of the celebration. Of equal note, however, one newspaper account asserts the 1883 parade marked Yeong Wo’s first celebration of Houwang’s birthday, claiming that earlier festivities had been held at a temple on Cum Cook Alley, an area known as Chinatown’s redlight district. These conflicting accounts cannot be fully reconciled at present.

Moreover, it has been suggested, by myself and others, that in 1885 the Yeong Wo Association or Houwang Temple might have occupied 730 Jackson [#28] during Houwang’s birthday festivities that year. The singular evidence for this, however, appears to derive from an error in the San Francisco Chronicle. By contrast, the San Francisco Examiner reports the Yeong Wo parade of that year passed by 730 Jackson which was occupied by Eastern Glory Temple, an occupant that makes more sense given the time frame of the mid-1880s [see #14].

The Yeong Wo Association finally relocated to Sacramento Street in September 1887, nearly twenty years after such a move was first reported. This transition was marked by an especially elaborate birthday parade for Houwang, who was ceremonially transported to his newly sanctified abode. A rudimentary newspaper sketch depicts the diminutive icon, echoing the early observer who likened it to a child’s doll (see below). The procession featured a massive serpentine dragon constructed from brown packing paper covered in silk, measuring 170 feet in length – more than three times longer than the fifty-foot dragon used the previous year (see sketch of mask below). The dragon alone reportedly cost $2,000, while the entire celebration was said to have cost $50,000. Houwang’s annual birthday festivities, characterized by raucous parades and spectacle, continued to attract public attention and press coverage through 1906.

Amédée Joulin (1862–1917), a French-American painter born in San Francisco, is reputed to have painted the interior of the Yeong Wo temple in 1890. Two newspaper illustrations also depict the temple elaborately decorated for festival occasions (see all below). After the 1906 earthquake the Yeong Wo shrine hall was not replaced.

36. Hop Wo Association I (Hehe huiguan 合和會館) & Six Companies I (Zhonghua huiguan 中華會館)

736 Commercial Street | 1887 Sanborn

The Hop Wo Association splintered from the Sze Yup Association in 1862 and rented space at 736 Commercial Street through the late 1860s. City directories from this time also list the headquarters of the Chinese Benevolent Association at the same address, noting they were “sustained by the Hop Wo Company.” The Chinese Benevolent Association would come to be known as the Chinese Six Companies. Both organizations moved in the mid-1870s when the Hop Wo Association purchased a building a few doors down on Clay Street [see #37 & #38]

37. Six Companies II (Zhonghua huiguan 中華會館)

728 Commercial Street