The most widely published Meiji era (1868-1912) photographer was undoubtedly Enami Nobukuni 江南信國 (1859—1929), who worked under the professional alias T. Enami.[1] His shop in Yokohama was a few doors down from his legendary competitor and colleague, Tamamura Kōzaburō 玉村康三郎 (b. 1856), who hired Enami to help complete his order of one-million hand colored albumen prints for the multi-volume work Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese, edited by Captain Francis Brinkley. Enami was expertly skilled in working with all of the popular photography formats, including larger-format prints, souvenir albums, portraiture, and glass lantern slides, but his most significant contributions were in the field of stereophotography. In addition to his considerable expertise, Enami fortuitously also worked during the “Golden Age” of Japanese themed stereoviews, roughly corresponding to the first decade of the twentieth century.

While Enami sold stereoviews under his own imprint in Japan, it was American and European publishers who bought the rights to sell his views that popularized Enami’s work abroad. As was standard practice at the time, publishers often omitted the names of photographers on stereocards, and thus even though American audiences may not have been acquainted with Enami’s name, his eloquent aesthetic vision was integral in shaping Western perceptions of Japan. The first major consigner of Enami’s stereoviews was Griffith & Griffith, a firm who first started issuing Enami’s views of Japan as odd-lots in 1900. Five years later, in response to the wildly popular box sets offered by competitors, H.C. White, C.H. Graves, and the Underwoods, Griffith & Griffith debuted their inaugural 100-view set of Japan, comprised entirely of Enami stock. The set was revised in 1907, adding variant Enami images. In the intervening years since 1900, Enami’s reputation had grown considerably among the largest publishers of stereocards, and his images were being incorporated into sets issued by C.H Graves, Underwood & Underwood, and T.W. Ingersoll. This continued until the market was consolidated under the massive portfolio acquisition by the Keystone View Company, which then continued to publish Enami’s work several decades into the twentieth century.

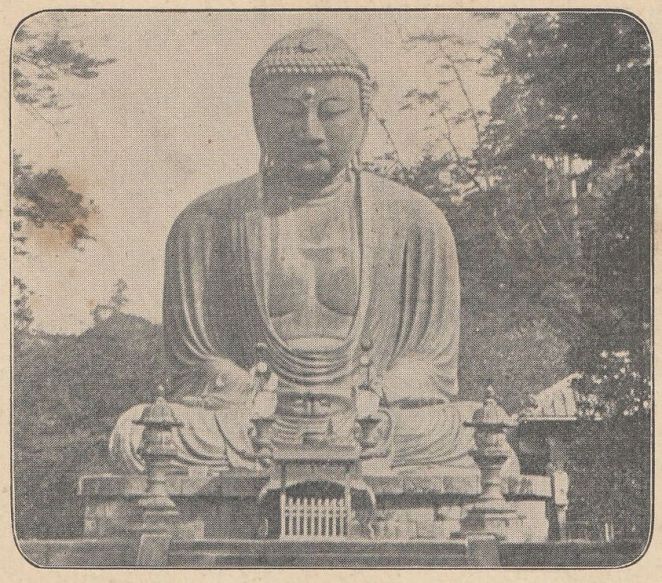

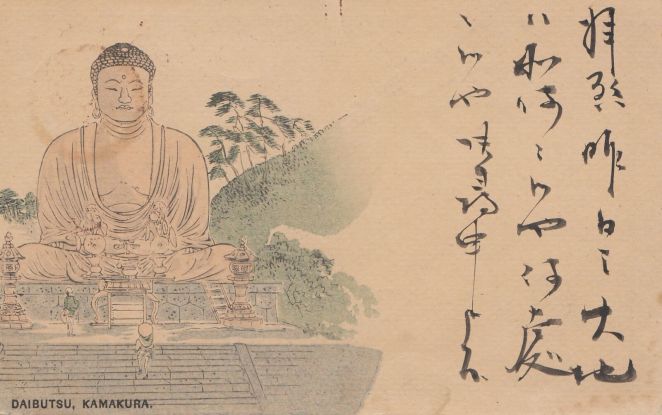

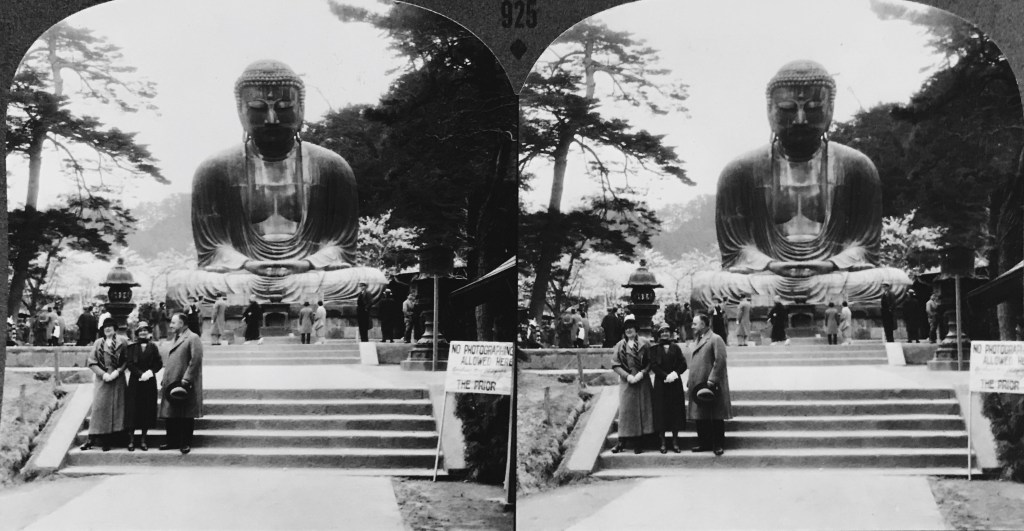

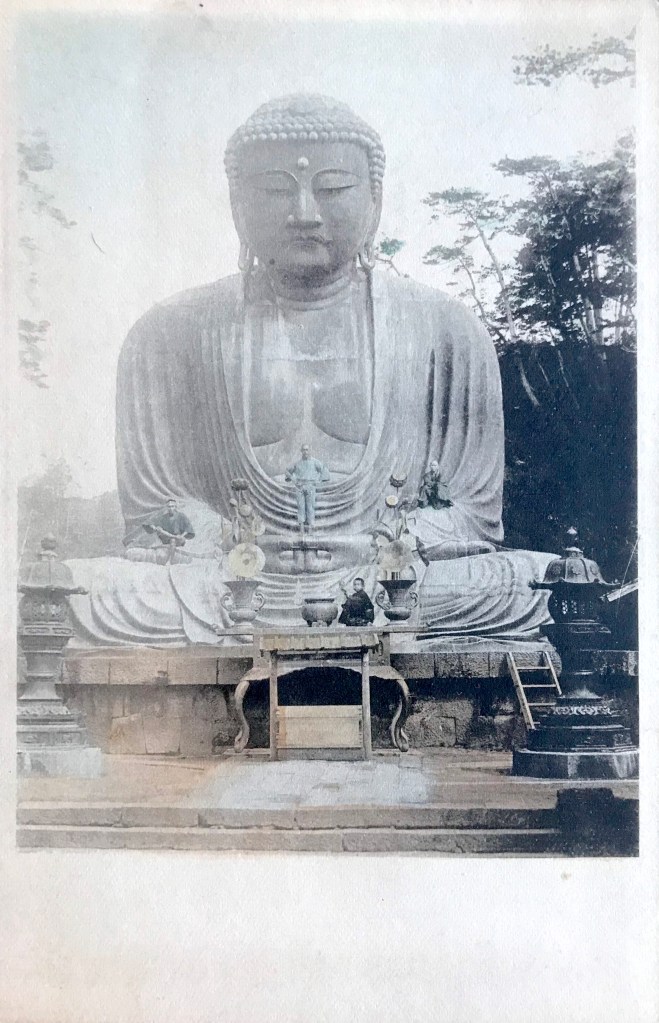

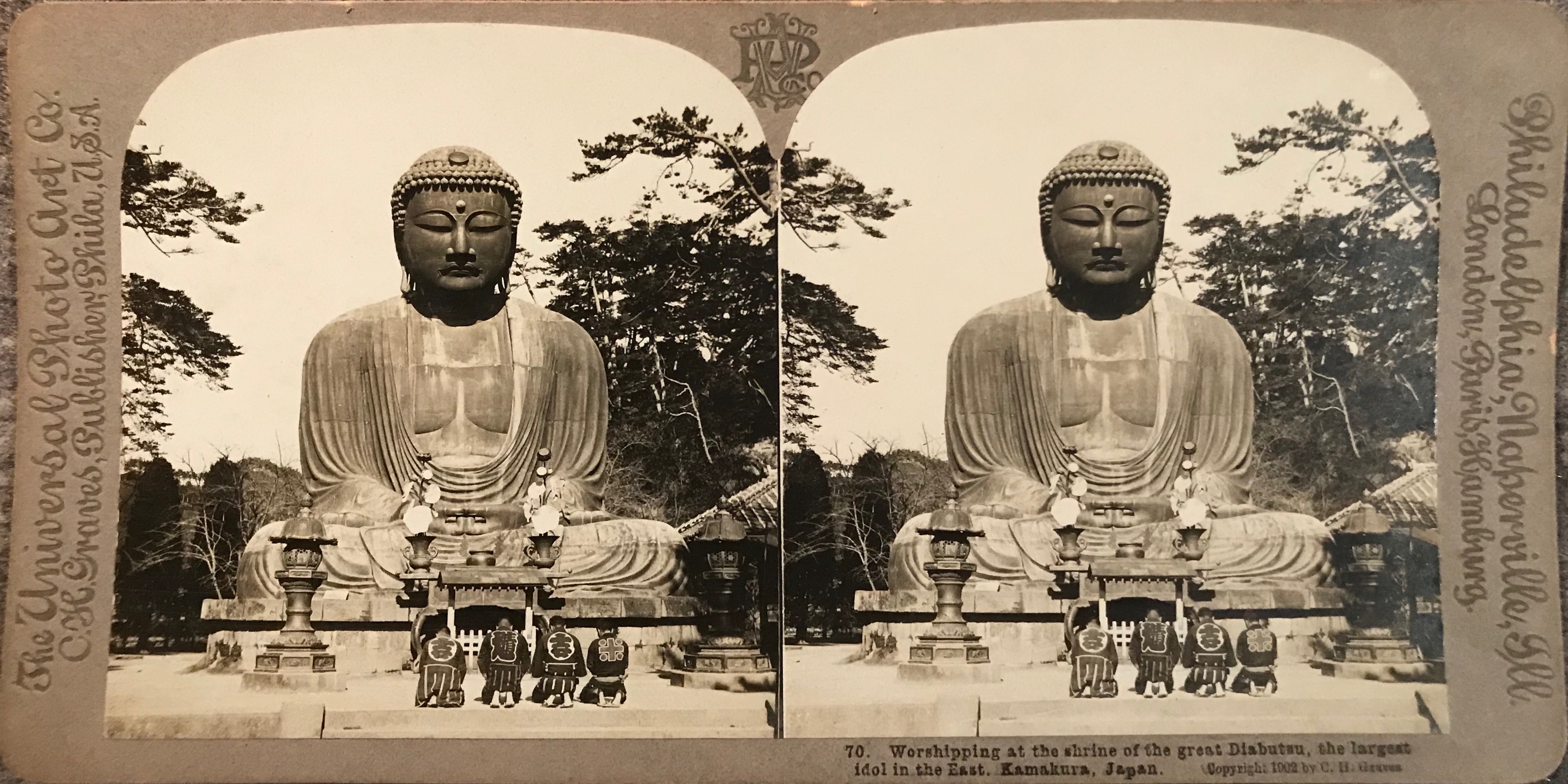

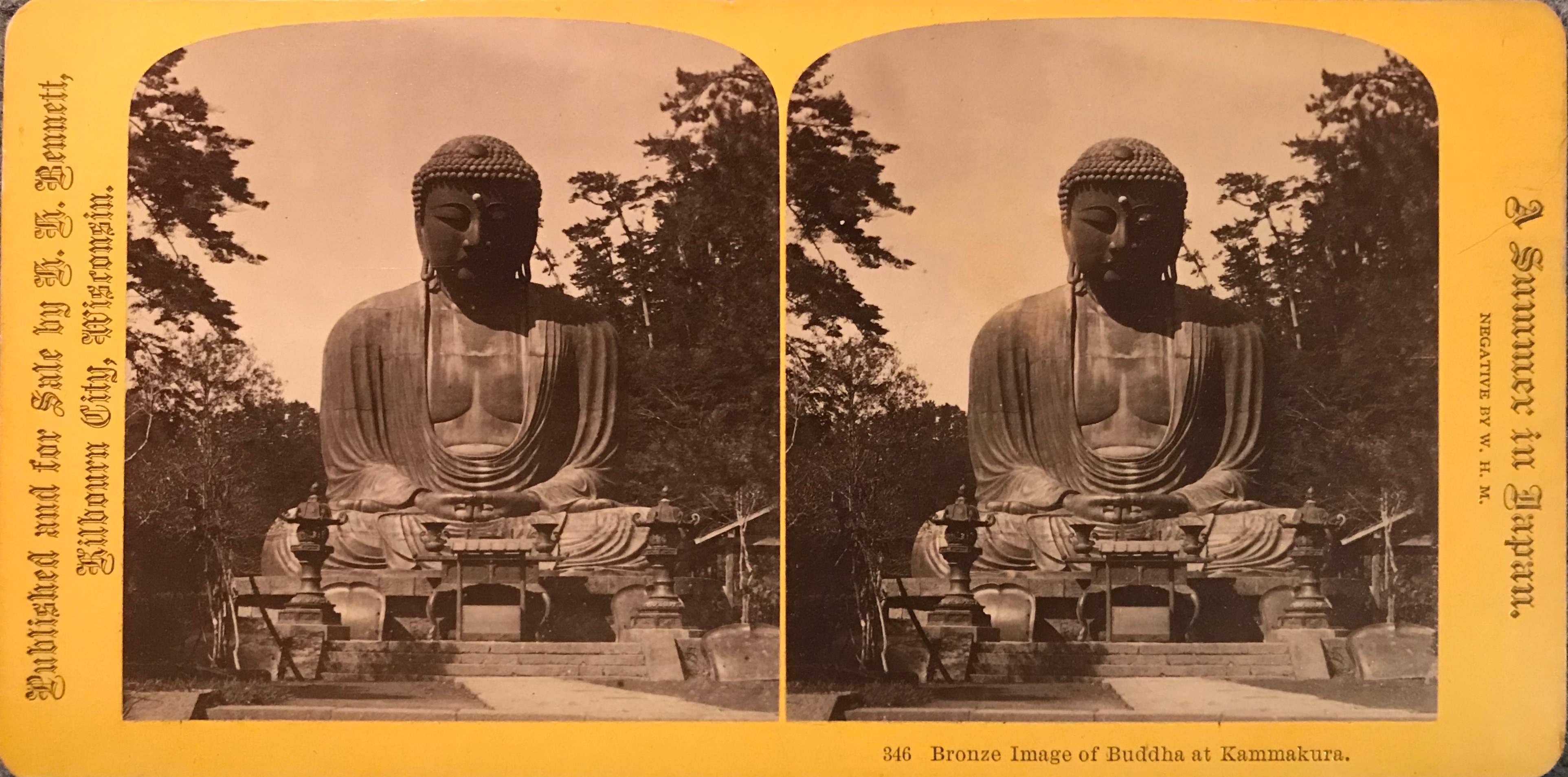

- Title/Caption: The Large Bronze Buddha, Kamakura, Japan

- Year: 1907

- Photographer: Enami Nobukuni 江南信國 (1859-1929)

- Publisher: Griffith & Griffith

- Medium: sliver gelatin print; mounted on curved slate-colored card

- Dimensions: 7 in X 3.5 in

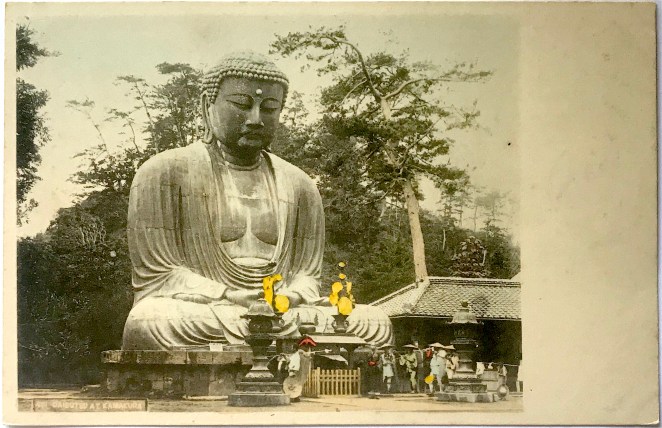

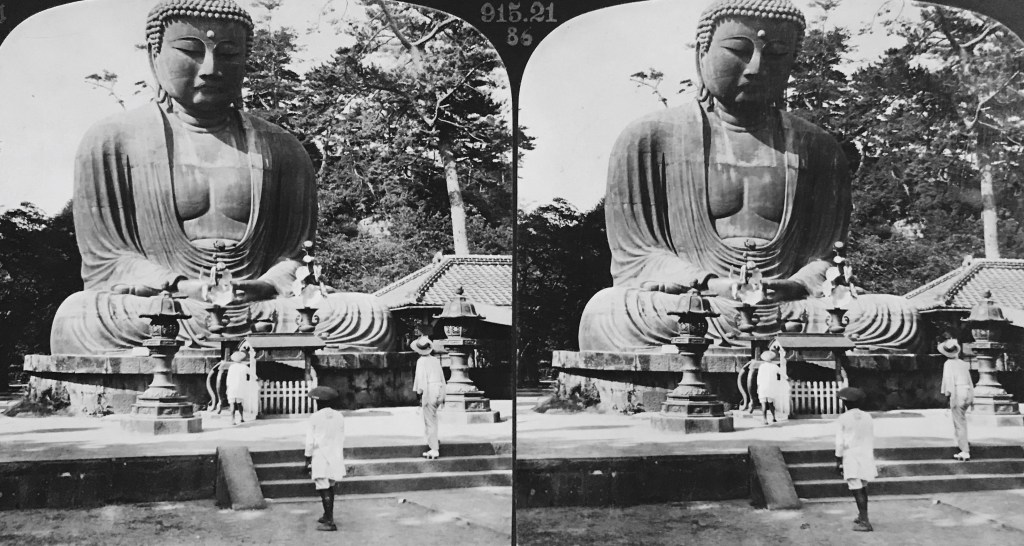

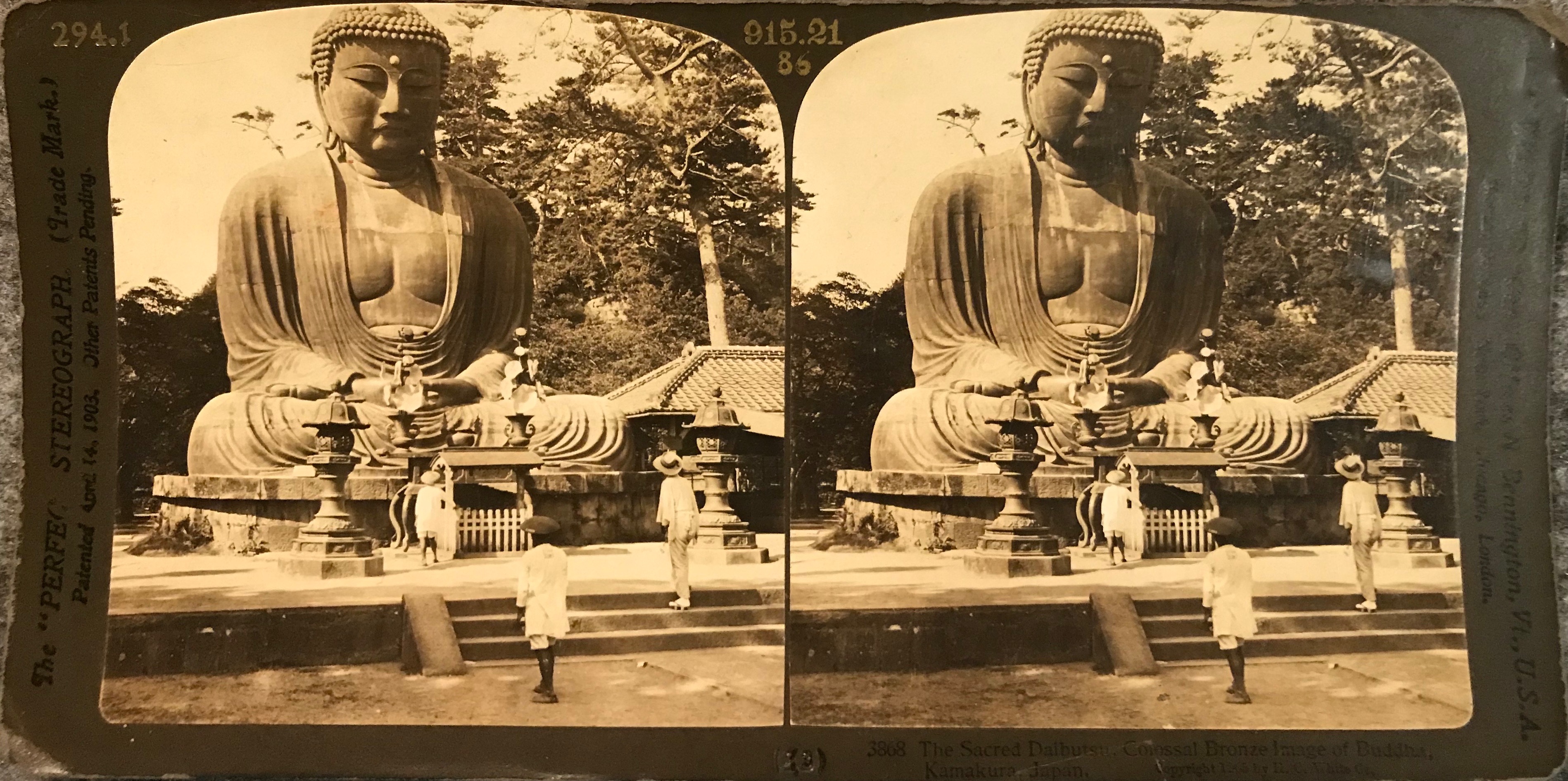

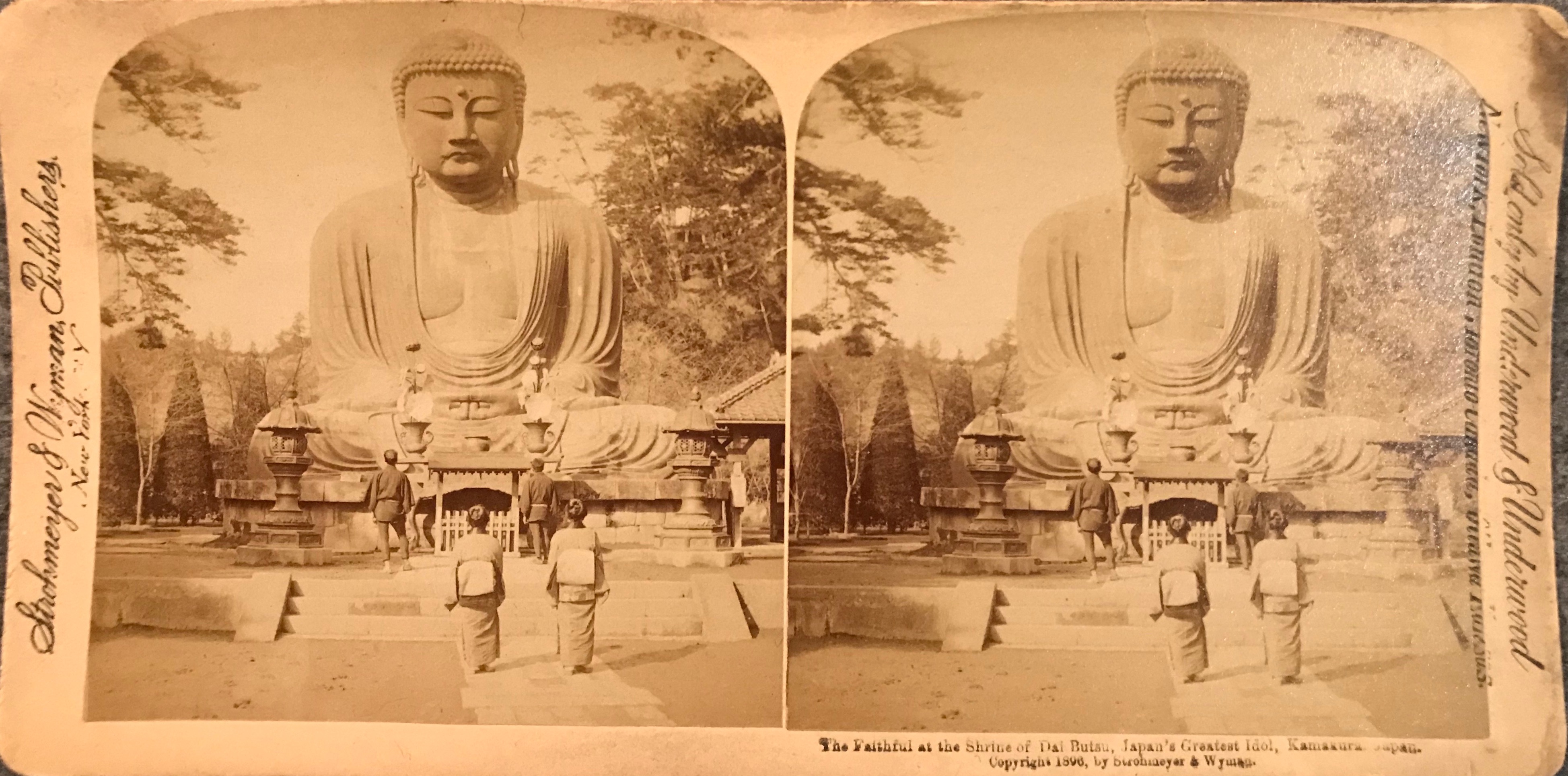

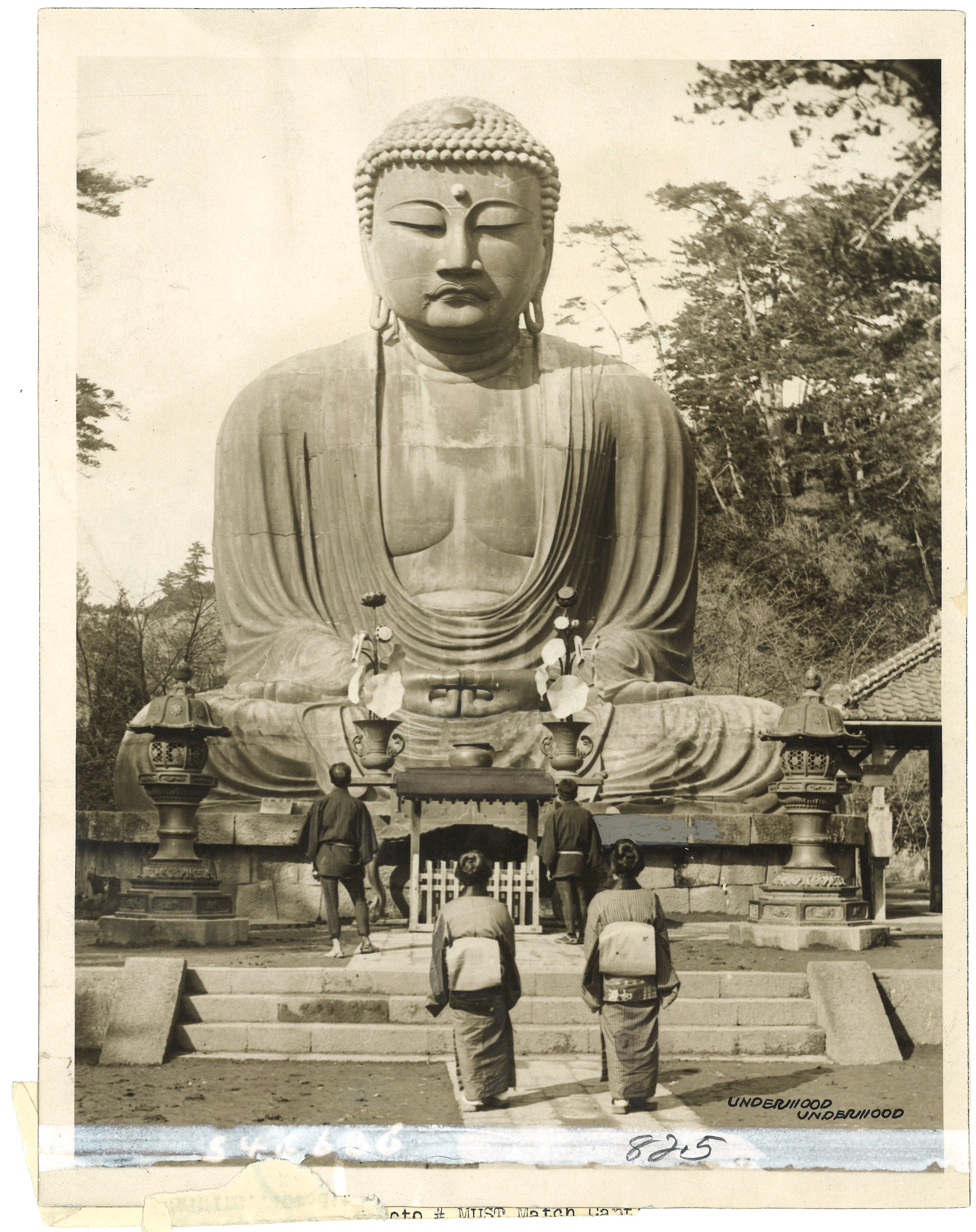

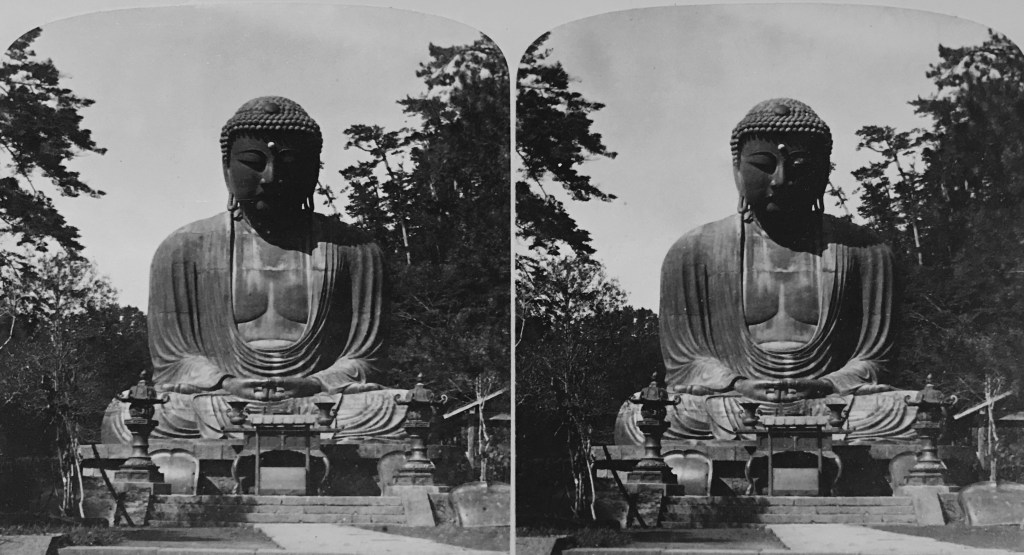

Of the views acquired by Griffith & Griffith, Enami’s treatment of the Daibutsu is among the most stunning. While many collectors consider the images of Herbert George Ponting (1870-1935) to be the pinnacle of Japanese stereophotography (Enami is often considered a close second), it is clear that Ponting took his cues in photographing the Daibutsu from Enami’s masterclass in layering and composition. It appears that most of Griffith’s Enami stock was originally photographed between 1895 and 1900, thus making this image, with the possible exception of Strohmeyer’s 1896 work, among oldest of the major publishers’ views of the Daibutsu [EDIT: It appears this image was taken after 1903]. Yet it also remains the most unique and sophisticated.

Setting his camera on the first landing, the furthest from the statue, Enami is able to visually narrate a story unlike his Western contemporaries. The viewer enters the image through the Japanese man at the lower right, who is photographed mid-stride ascending a small flight of steps. Due to the positioning of his head, the viewer presumes his gaze is directed at the woman and two small children down the pathway in front of him. The two children gaze back at him, creating a strong sense that we are observing a family about to reunite. Alone, this visual narrative is strikingly different from the images produced by Western photographers, who tend to highlight the pious religiosity of the Japanese people or the aesthetic qualities of the Daibutsu. Here the Kamakura statue is simply the location where the family gathers, presumably to pray and ask for blessings. There is no overt signaling of awe-struck piousness or odd bodily positioning rendering the scene unnatural. Furthermore, by placing the dwarf palm in the foreground with the man, partly obscuring the view of the Daibutsu, we are afforded a sense of entering a liminal space, within which we find family, safety, and serenity. There is a technical reason for incorporating these foreground elements as well, they would provide a greater illusion of depth when observed through a stereographic viewer.

In addition, there are also signs that Enami was trying to appeal to a Western clientele, most visibly through the elaborate dress. While operating out of his shop in Yokohama, Enami’s premier customer base were Western globetrotting tourists looking to capture a piece of the exotic orient, most typically through the conspicuous ownership of photography. By dressing his subjects in formal and decorative garments, Enami was still able to signal a sense of the Other so prized in souvenir memorabilia, while not fully embracing a hypersexualized or hyper-religious Oriental discourse.[2]

![1921 July "The Geography of Japan" - Weston [National Geographic] p64.jpg](https://peterromaskiewicz.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/1921-july-the-geography-of-japan-weston-national-geographic-p64.jpg)

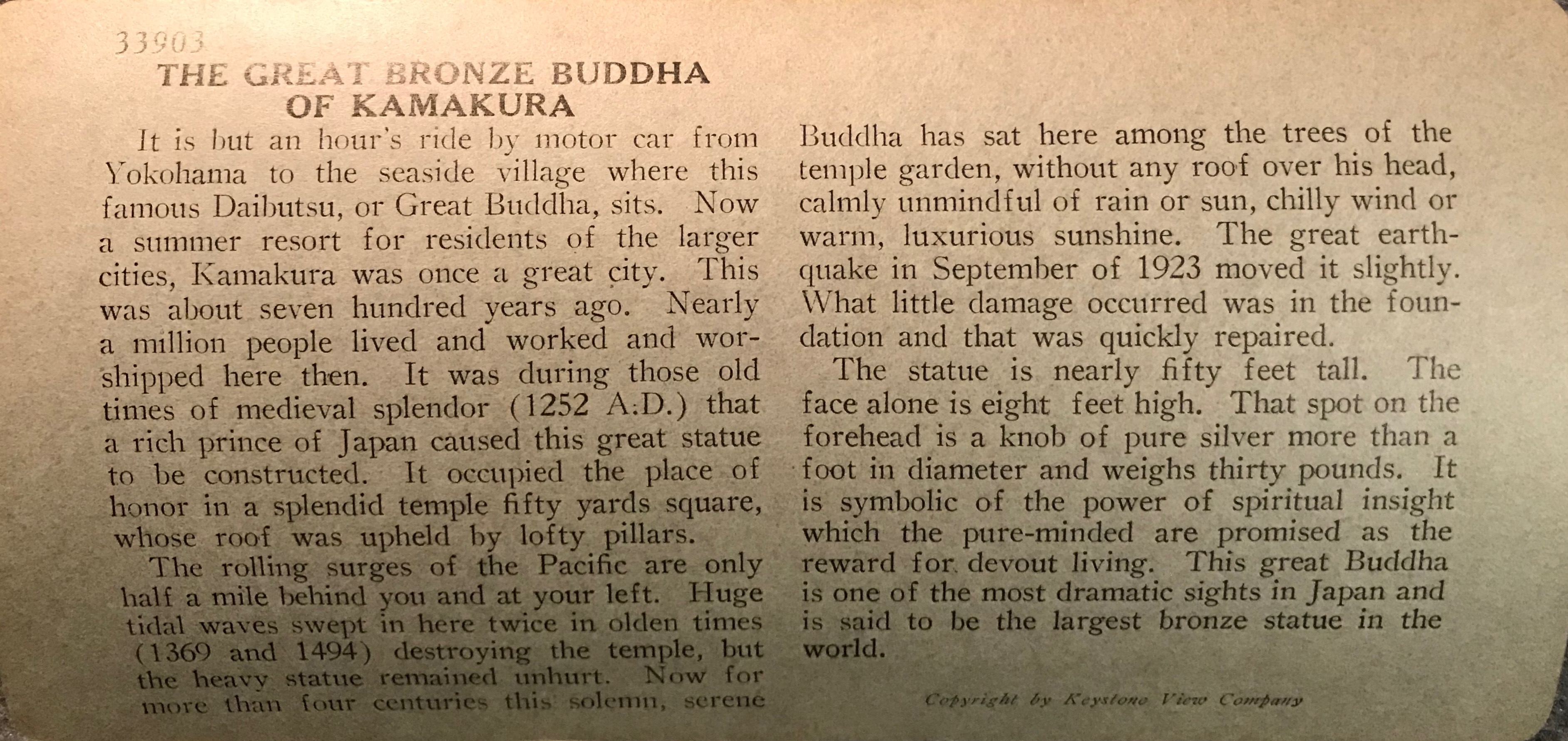

The other valued and incomparable skill of Enami was his ability to beautifully hand-tint his photographs. Japanese assistants had long been assigned hand-coloring tasks in the Western photography studios of Yokohama, and Enami and his workshop produced some of the most meticulous work. A wonderfully colored variant of the Griffith & Griffith view (likely of the “seconds or minutes” variety, meaning both shots were taken in close time proximity of one another) appeared in the pages of National Geographic in July 1921 (pg. 64/pl. IV), showcased along some of the finest journalistic photography of the twentieth century. It is possible the National Geographic variant was originally a stereograph, as Enami regularly used one half of the stereographic negative for his two-dimensional images.

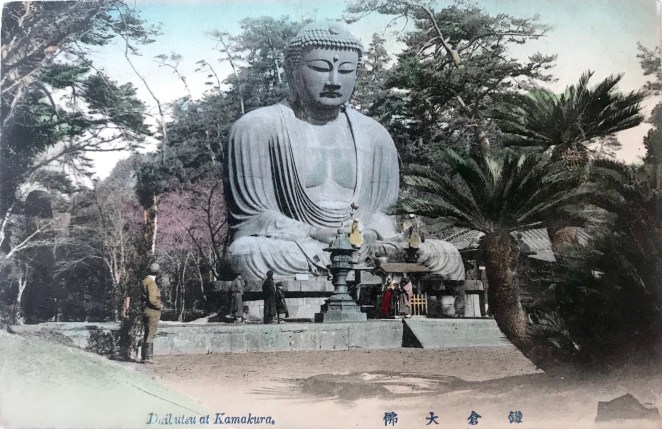

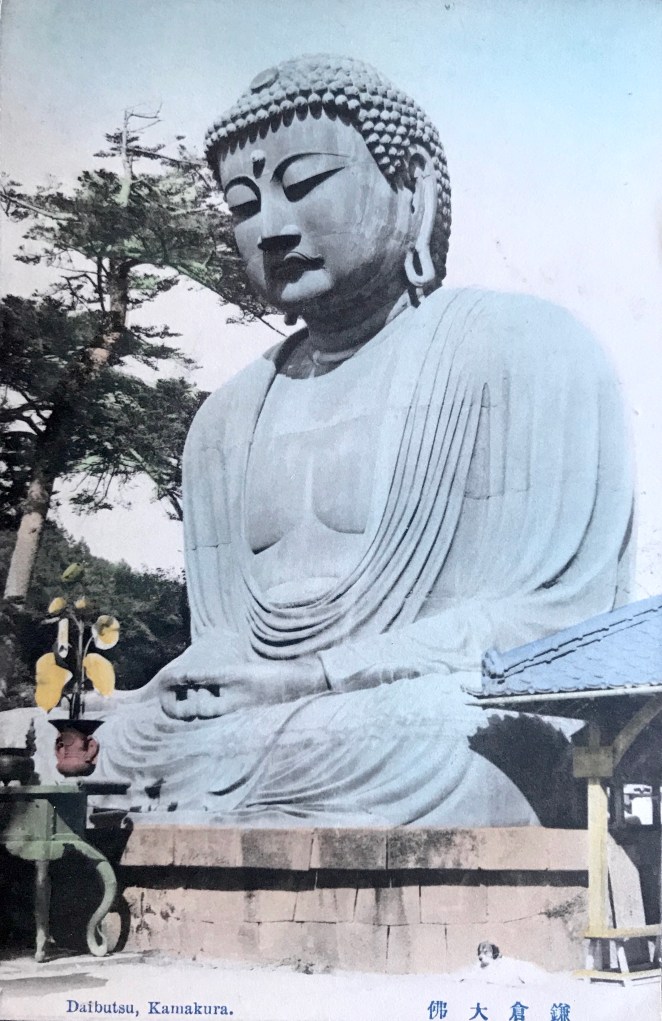

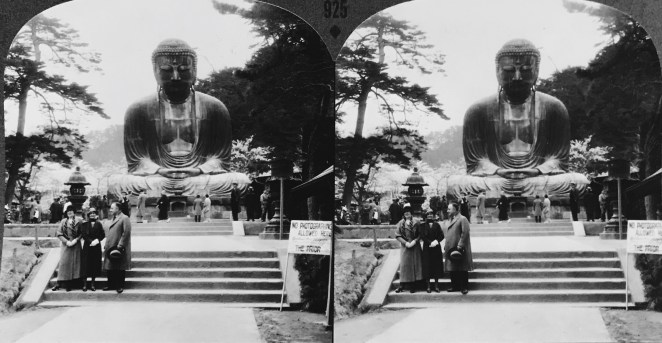

- Title/Caption: Götzenbild, Japan [“Idolatry, Japan”]

- Year: (modern reprint of 1912 original)

- Photographer: Enami Nobukuni 江南信國 (1859-1929)

- Publisher: Universal Stereoscop Company

- Medium: (modern reprint on photographic paper)

- Dimensions: 7 in X 3.5 in

The Central European agency responsible for distributing Griffith & Griffith views was the German firm Nueu Photographische Gesellschaft (NPG), who published a series of 50 Enami views. In 1912, the German publisher Universal Stereoscop Company reissued the NPG stock, adding 50 additional views to make a full 100-view set. Unlike the original production run in the US, Enami’s German images were sold tinted, thus further enhancing the astonishing brilliance of Enami’s work.

Notes

*This is part of a series of posts devoted to exploring the development of a visual literacy for Buddhist imagery in America. All items (except otherwise noted) are part of my personal collection of Buddhist-themed ephemera.

[1] For more detailed information on the surprisingly elusive life of Enami, see Bennett 2006, and especially the sleuthing of Oechsle 2006. Rob Oechsle also runs the excellent site dedicated to Enami’s oeuvre, t-enami.org.

[2] The ability of Asian agents to navigate and sometimes subvert Orientalist discourses have been encapsulated by several theories of resistance, of which John Kuo Wei Tchen’s notion of “commercial Orientalism” is appropriate here, see Tchen 1999.

References

- Bennett, Terry. 2006. Old Japanese Photographs Collector’s Data Guide. London: Bernard Quaritch Ltd.

- Oechsle, Rob. 2006. “Searching for T. Enami,” in Old Japanese Photographs Collector’s Data Guide, by Terry Bennett. London: Bernard Quaritch Ltd, pp. 70-8.

- Tchen, John Kuo Wei. 1999. New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Additional Posts in Visual Literacy of Buddhism Series