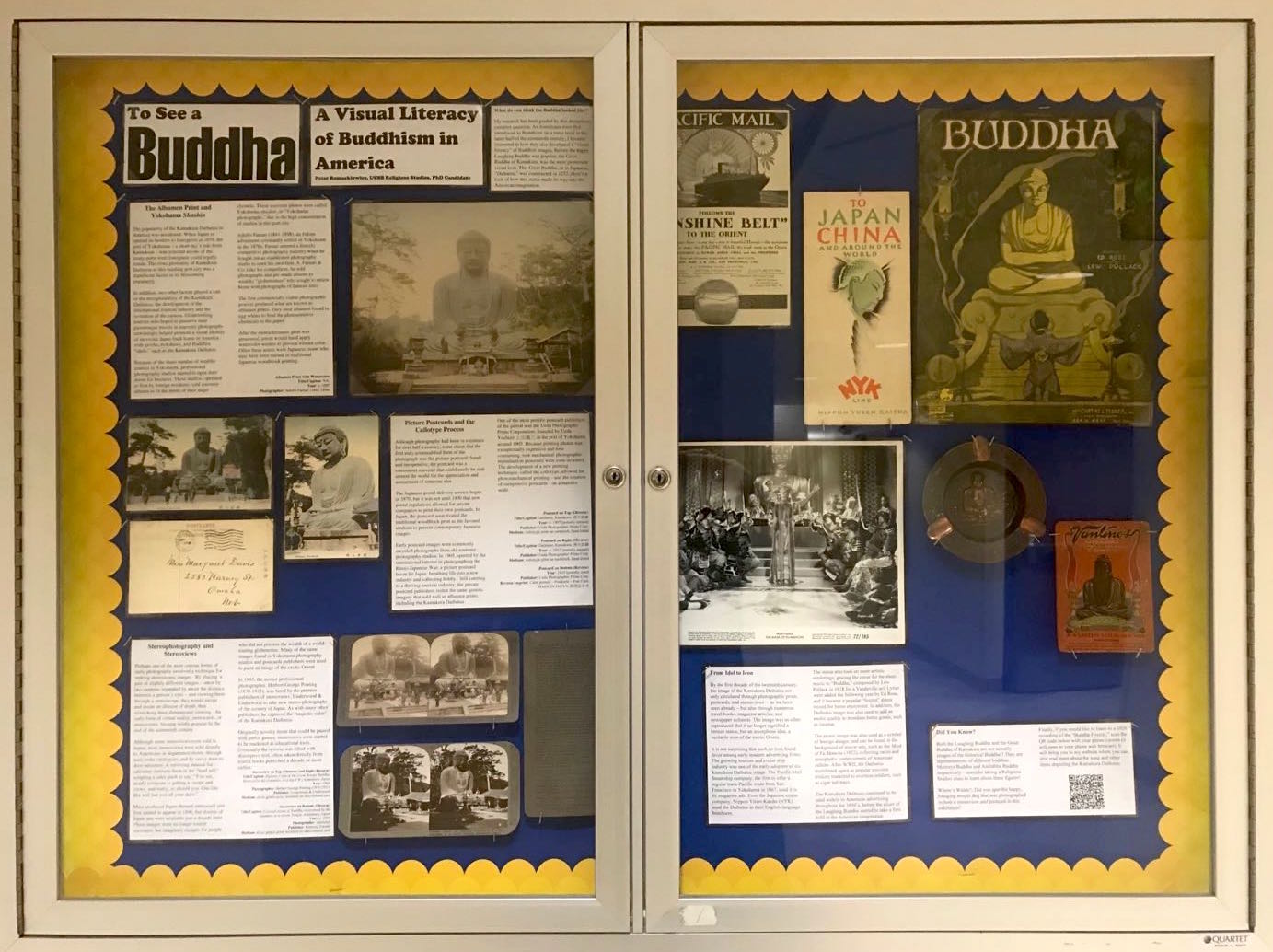

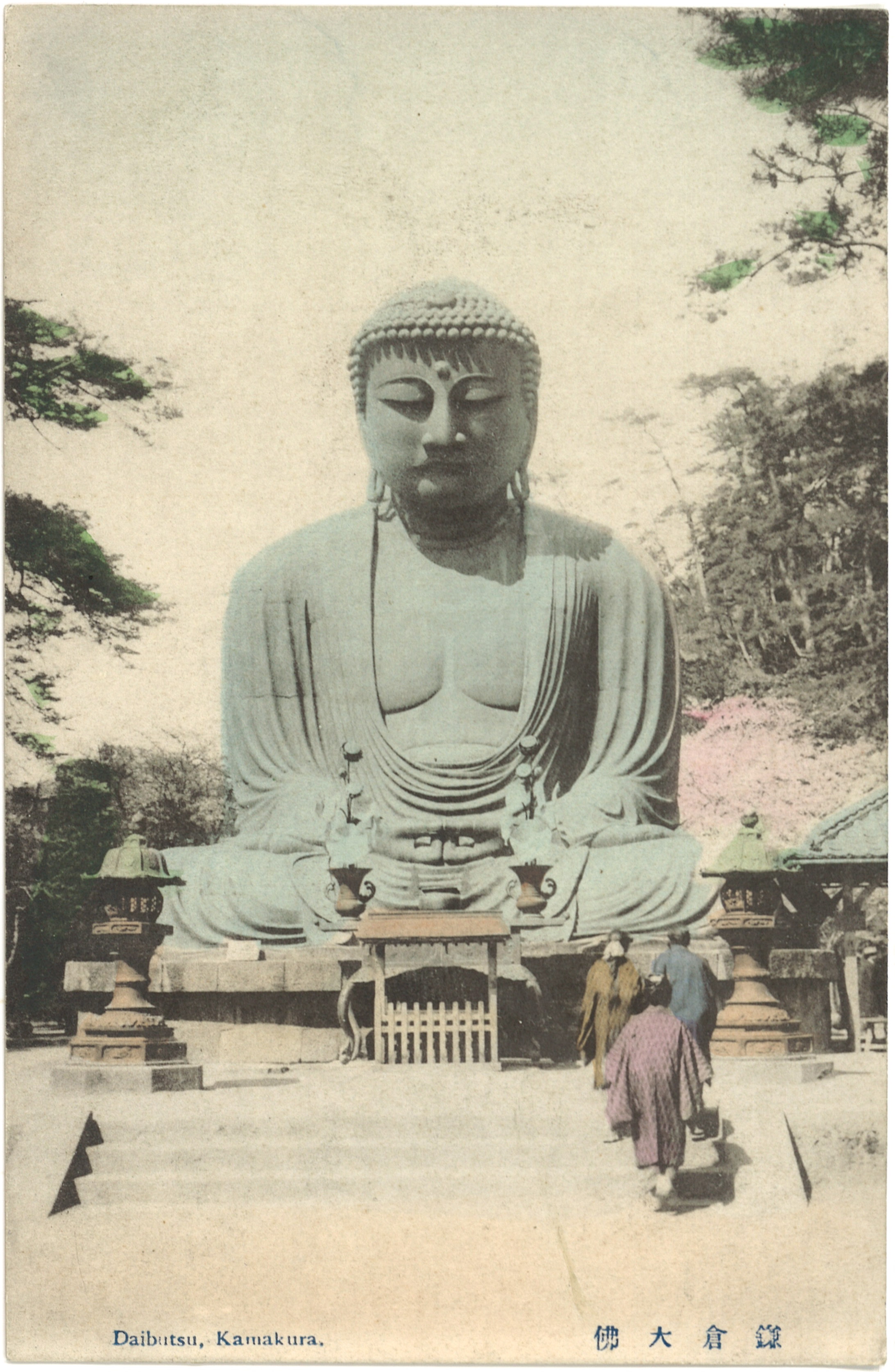

On October 16, 1909, the S.S. Cleveland left Hoboken, New Jersey on the first commercial around-the-world cruise. American tour operator, Frank C. Clark, chartered the Cleveland from the German operated Hamburg-American Line, leaving the east coast with a party of 650 passengers and traveling eastward through the Suez Canal before making landfall in San Francisco three months later on January 31, 1910. Because the Panama Canal was four years away from completion, the passengers completed the last leg of the around-the-world tour via train, returning to their origin point on the east coast. Thus, although Clark’s cruise was not a complete circumnavigation of the globe, the public and press treated it as such. Five days after landing in San Francisco, the Cleveland re-crossed the Pacific Ocean to start a second around-the-world tour, this time carrying more than 750 passengers. Clark’s pair of world tours generated significant amounts of publicity, with thousands appearing in San Francisco to send the ship off. The Cleveland made several subsequent trips between 1912 and 1914 until the advent of World War I interrupted access to the German-owned vessel.[1] The standard itinerary for trans-Pacific cruises of the period included a longer stopover in the port of Yokohama. Here, passengers could go ashore and enjoy the local sites, including a visit to the Kamakura Daibutsu.

One of the most popular publishers of stereocards, Underwood & Underwood, took advantage of these widely marketed luxury world tours and assigned a stereo-photographer to accompany the guests aboard the Cleveland to chronicle the trip. These new stereophotographs then became stock in Underwood & Underwood’s massive catalogue of Japan views and marketed to the general public.

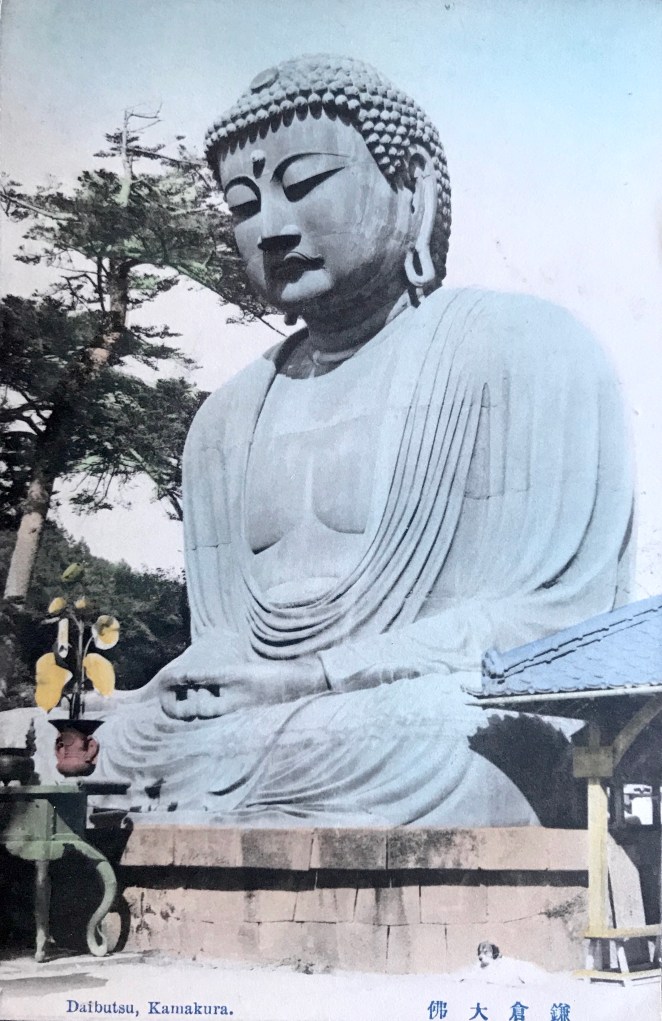

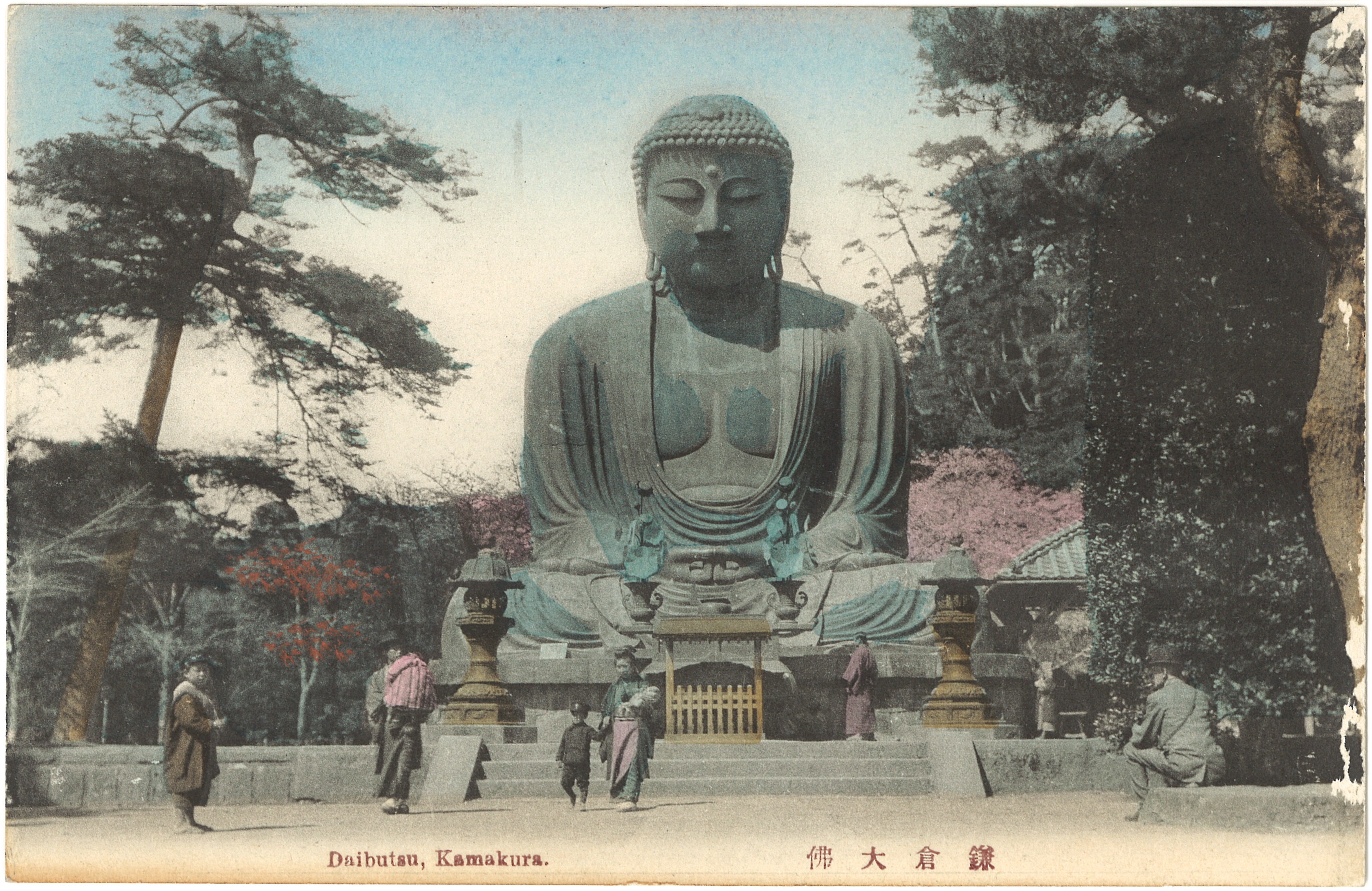

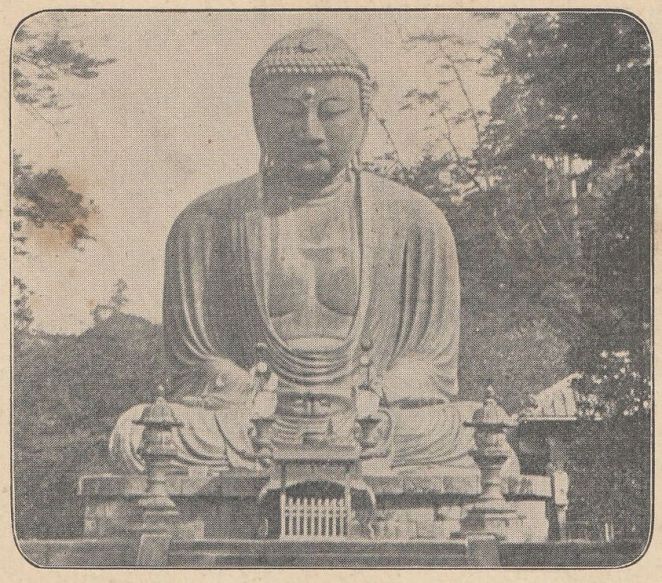

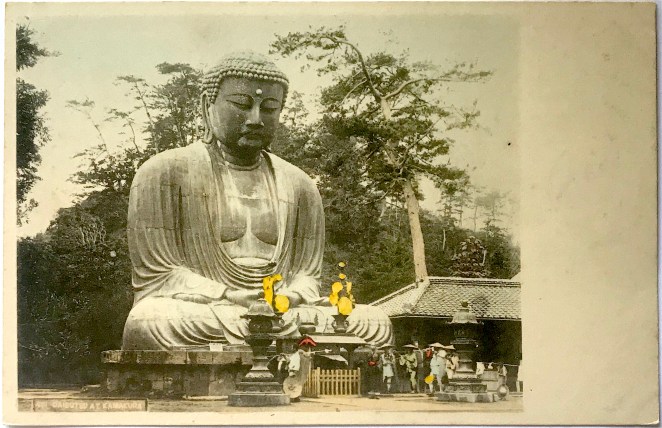

Figure 1

- Title/Caption: 298-Daibutsu, Kamakura, Japan

- Year: 1913-1914

- Photographer: unknown

- Publisher: Underwood & Underwood

- Medium: sliver gelatin print; mounted on curved slate-colored card

- Dimensions: 7 in X 3.5 in

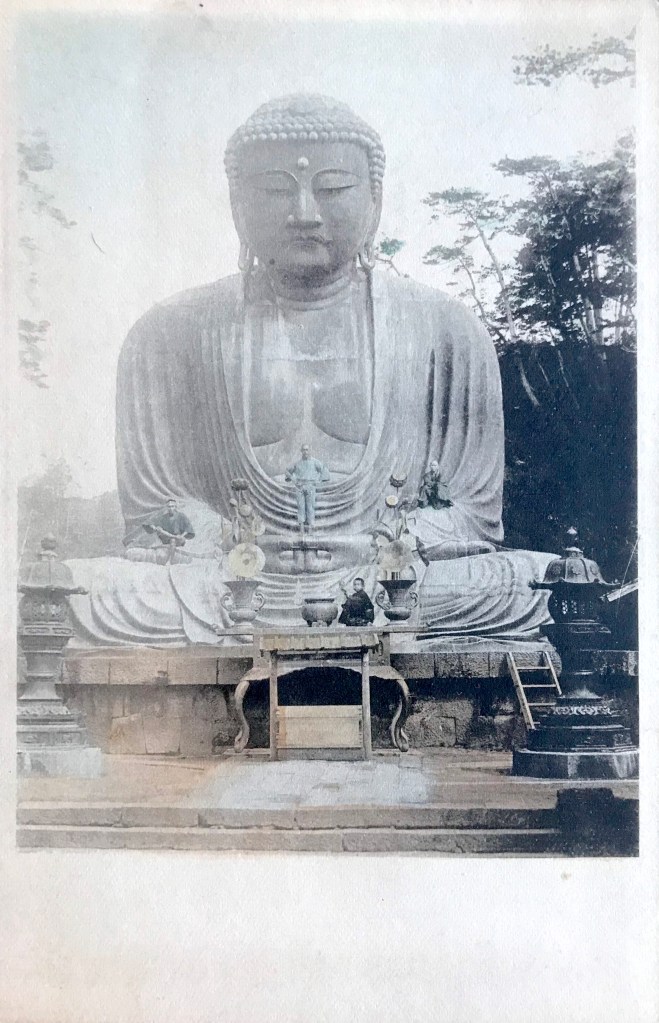

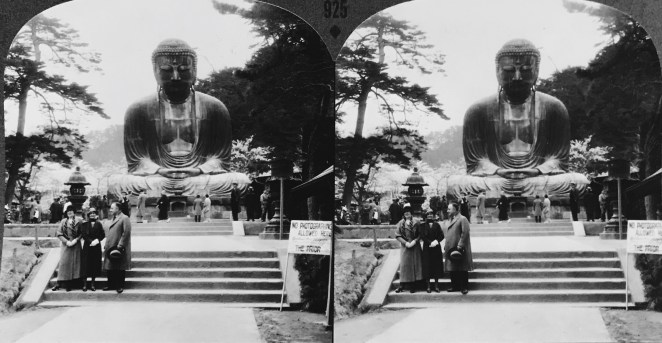

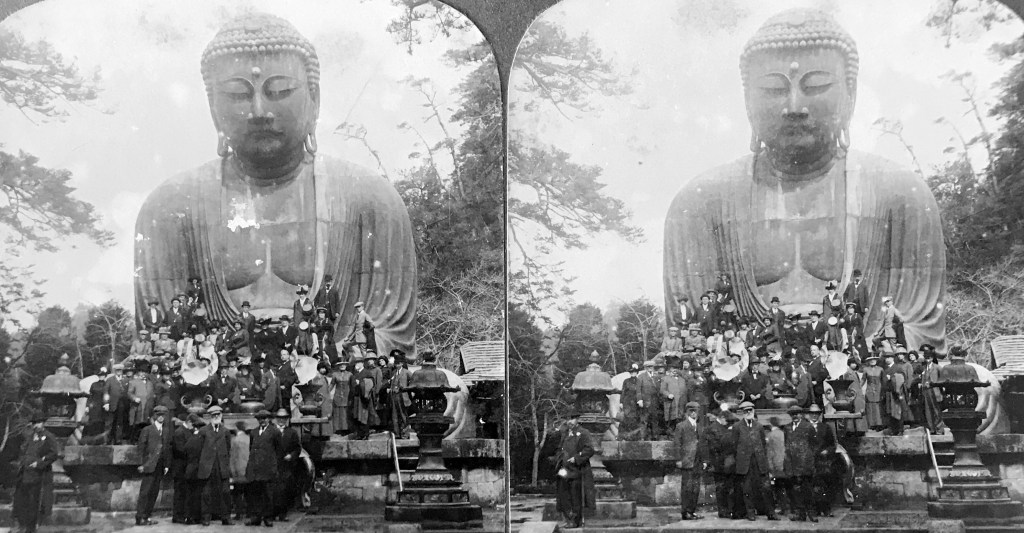

According to the account of R. H. Casey, a passenger aboard the Cleveland during its fourth trip across the globe which arrived in Japan on February 24, 1913, the tourist excursion trips were a sight to behold. Two hundred and forty passengers boarded a train to Kamakura and rode rickshaws from the train station to the temple of the Daibutsu, traveling en masse through the narrow roads of the rustic city’s back country.[2] This feeling of mass tourism is captured perfectly by our unknown photographer’s view, showing a cluster of nearly fifty people crowded in front of the Daibutsu [Fig. 1]. Almost all of the visitors are mounted atop the stone foundation or posing in the lap of the colossal statue. This posturing of gazing towards the viewer reflects a long-standing photographic tradition of collecting exotic “trophies” by being pictured in front of one’s cultural conquests.

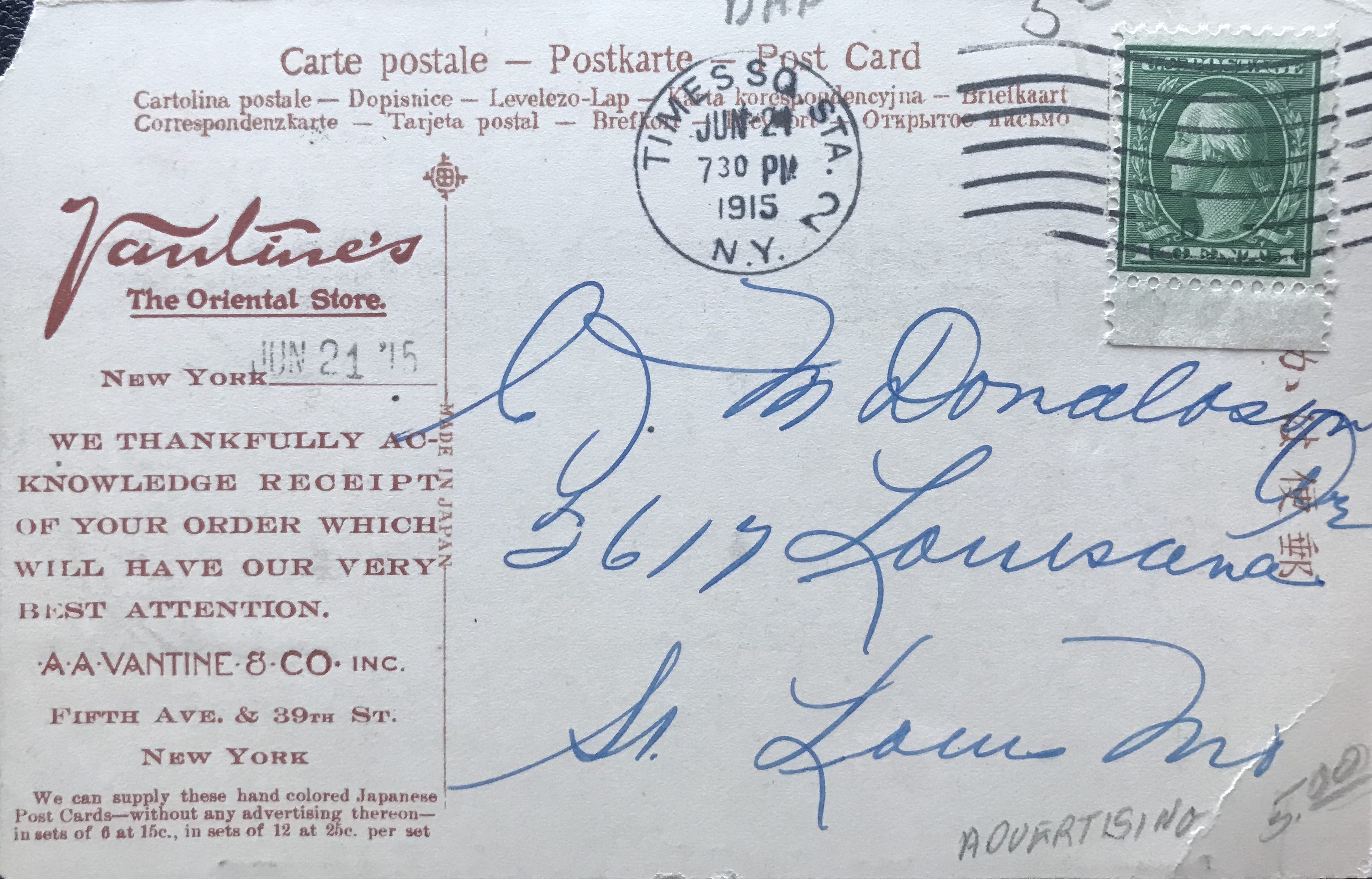

The card itself does not identify the party as originating from the Cleveland, but an adjacent card in the Underwood & Underwood catalogue (number 247, Fig. 2), does identify a large group of tourists perched along the tall stairway of Hachiman Shrine as traveling aboard the Cleveland. Moreover, a close inspection of these two photographs reveals the same individuals are depicted in both.[3] Thus, we can safely assume the visitors to the Daibutsu are among the globetrotters aboard the Cleveland.

Figure 2

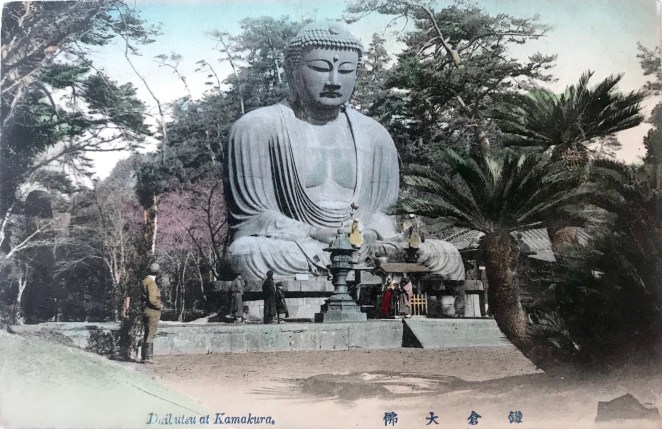

It is difficult to determine which around-the-world cruise this group of people joined. Photographs from the initial pair of Clark’s trips, between 1909-1910, show the Daibutsu site displaying a picketed fence and gabled roof on the coin offering box (saisen–bako 賽銭箱), elements that appear – to my eye – to be missing in this stereoview.[4] It is possible this image was taken on one of the second pair of cruises, landing in Yokohama in January and February 1913, having departed from Hoboken and San Francisco respectively.[5] A fifth, and likely final, cruise aboard the Cleveland was scheduled to depart the east coast in January 1914 on a 93-day voyage to San Francisco, with no scheduled “return” trip.[6] Thus, it appears this photograph of the Daibutsu could have been taken during one of these three trips during 1913 or 1914.

In contrast to the other Underwood & Underwood view of tourists atop the Daibutsu, this composition has the feeling of formal portraiture. The visitors are spread out symmetrically along the ground, statue, and stone base, with most looking sternly at the camera lens. As around-the-world cruises became more popular in the interwar period, these large group photos also became more common, sometimes being used in promotional material for the cruise company. The photographs of the 1860s and 1870s that depicted small groups of intrepid travelers (and mostly men), were now festooned with tourists who draw as much attention to themselves as the statue in the background.

Notes:

*This post is in honor of my father, may your curiosity in the odd live on through me.

*This is part of a series of posts devoted to exploring the development of a visual literacy for Buddhist imagery in America. All items (except otherwise noted) are part of my personal collection of Buddhist-themed ephemera.

[1] The Hamburg-American Line advertised heavily for the Cleveland’s first trip through the Panama Canal, scheduled to disembark from Hoboken in January 1915 and bring passengers to San Francisco to celebrate the Panama-Pacific Exposition. I have found no evidence that this trip took place, and given that Germany was in the midst of war by the end of 1914, the excursion was most likely to have been abandoned by the Hamburg-American Line. Accounts of the previous completed trips, where the above information was extracted, can be found in Frizell & Greenfield 1910, Junkin 1910, Bush 1911, Forbes 1912, and Casey 1914.

[2] Casey 1914: 29. According to Casey, they also visited the Kaihin Hotel.

[3] The easiest individual to spot is the sole hat-less man with coiffed white hair and mustache. A second man in a brimmed newsboy hat and white beard is also easily identified in both.

The distinctive plumes in women’s hats also leads to several relatively easy identifications (not pictured). Moreover, Underwood & Underwood Japan-series cards issued with numbers in the 290’s all appear to be issued from the Cleveland cruises.

[4] The photograph by amateur photographer F. H. Wellcome and published in the travelogue of Frizell and Greenwod clearly shows the gabled coin box. (see Frizell & Greenwood 1910: 49).

[5] These dates are noted in Forbes 1912: 27 & 29. Forbes took two trips around the world, starting in Hoboken and travelling eastward until ultimately landing in San Francisco, where he then joined the “return” voyage, heading westwards until back in Hoboken

[6] The Cleveland would have needed to be back in Hoboken for its widely publicized trip leaving in January 1915 (see note above). It is possible the Cleveland left San Francisco and headed for the Panama Canal, testing the crossing without passengers before returning in January. This tour was operated by the Hamburg-American Line directly and Clark would not make his fifth trip around the world until after the war in 1924, when he chartered the S.S. California.

References:

- Bush, George Tome. 1911. 40,000 Miles Around the World. Howard, PA: N.P.

- Casey, R. H. 1914. Notes Made During a Cruise Around the World in 1913. New York: N.P.

- Forbes, Edgar Allen. 1912. Twice Around the World. New York: Fleming H Revell Company.

- Frizell, William G. and Greenfield, George H. 1910. Around the World on the Cleveland. New York: N.P.

- Junkin, Paul S. 1910. A Cruise Around the World. Creston, IA: N.P.

Additional Posts in Visual Literacy of Buddhism Series

The back of the cartes de visite is stamped by Renjō’s studio mark in indigo blue [Fig. 2]. The hand stamp depicts two serpentine figures twisting around a pair of trees and peering into two pots. The peak of Mt. Fuji and the top of a thatched roof also appear the background. This specific imagery appeared to Renjō in a dream when his business first started to turn profitable, thus he decided to honor his vision by incorporating it into his studio mark. The Japanese characters, written in a variant script (itaiji

The back of the cartes de visite is stamped by Renjō’s studio mark in indigo blue [Fig. 2]. The hand stamp depicts two serpentine figures twisting around a pair of trees and peering into two pots. The peak of Mt. Fuji and the top of a thatched roof also appear the background. This specific imagery appeared to Renjō in a dream when his business first started to turn profitable, thus he decided to honor his vision by incorporating it into his studio mark. The Japanese characters, written in a variant script (itaiji