The Kamakura period (1185-1333) was a time of intense religious activity in Japan. In particular, Buddhist priests who promoted faith in Amitābha Buddha, a figure who resided in the Western Pure Land and taught those fortunate to be reborn there, were influential in shaping the future of Japanese Buddhism. The founder of the Ji School (Jishū 時宗) of Pure Land Buddhism, Ippen 一遍 (1239-1289), was among the more obscure of these figures, but traditionally he is given the honorific title, Shōnin 上人, a name reserved for the most eminent of Buddhist priests. He is perhaps most celebrated for his sixteen year period of homeless wandering as a holy mendicant during which he distributed small talismans bearing the name of Amitābha Buddha. A central practice of the Pure Land schools was reciting this buddha’s name, thus the practice was called nembutsu 念仏, “recalling [Amitābha] Buddha.” Ippen sought to encourage this salvific practice among as many people as he could reach. In 1289, he passed away in a hall dedicated to the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteśvara, in a small temple that would soon come to be known as Shinkōji 真光寺. Located in Hyōgo, far from the Japanese capital, Shinkōji never became a powerful center of Japanese Buddhism, but it’s connection to Ippen – as it would come to house his remains – would garner it a small bit of local fame.

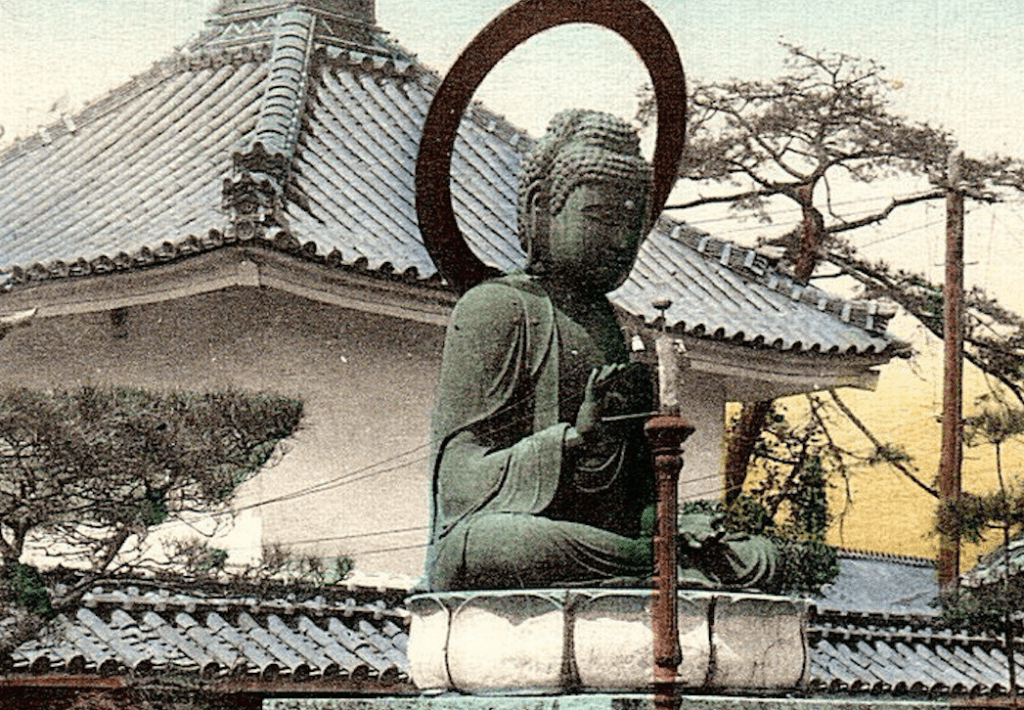

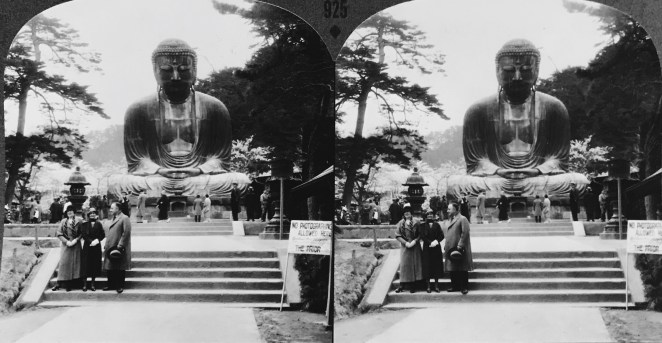

When foreign tourists first started traveling in large numbers to Japan in the last decades of the nineteenth century, Yokohama was the main port of entry for people traveling across the Pacific Ocean. The port of Hyōgo, which came to be subsumed by its neighbor Kōbe in 1892, was the next harbor that ships used when taking passengers further south along the Japanese coast. The ships would then eventually continue on to China, if not further west or even around the globe. This influx of travelers gave sites around the port of Kōbe more attention, of which Shinko-ji received a small share. For example, the temple was noted as being “worth a visit” by the widely circulated third edition of Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Japan, published in 1891.[1] It was also noted in Keeling’s Guide to Japan, a popular illustrated guidebook sold in Yokohama at Adolfo Farsari’s shop. The centerpiece for most foreign tourists was a large bronze statue of a buddha, situated outside the main temple gate. At a height of just under sixteen feet, the statue was not as colossal as the Great Buddha in Kamakura, but its placement in the middle of a lush lotus pond made it a picturesque and desirable location for visitors to enjoy. While some sources claim the Shinkōji statue depicts Amitābha Buddha, the iconography suggests Vairocana Buddha, an identification substantiated by Shinkōji today.

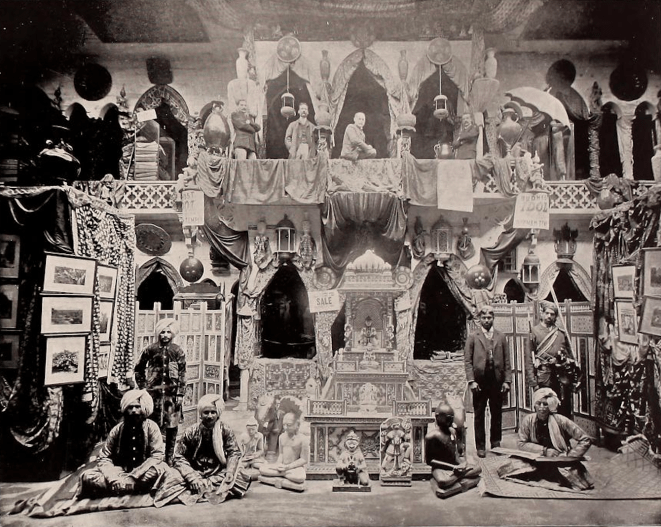

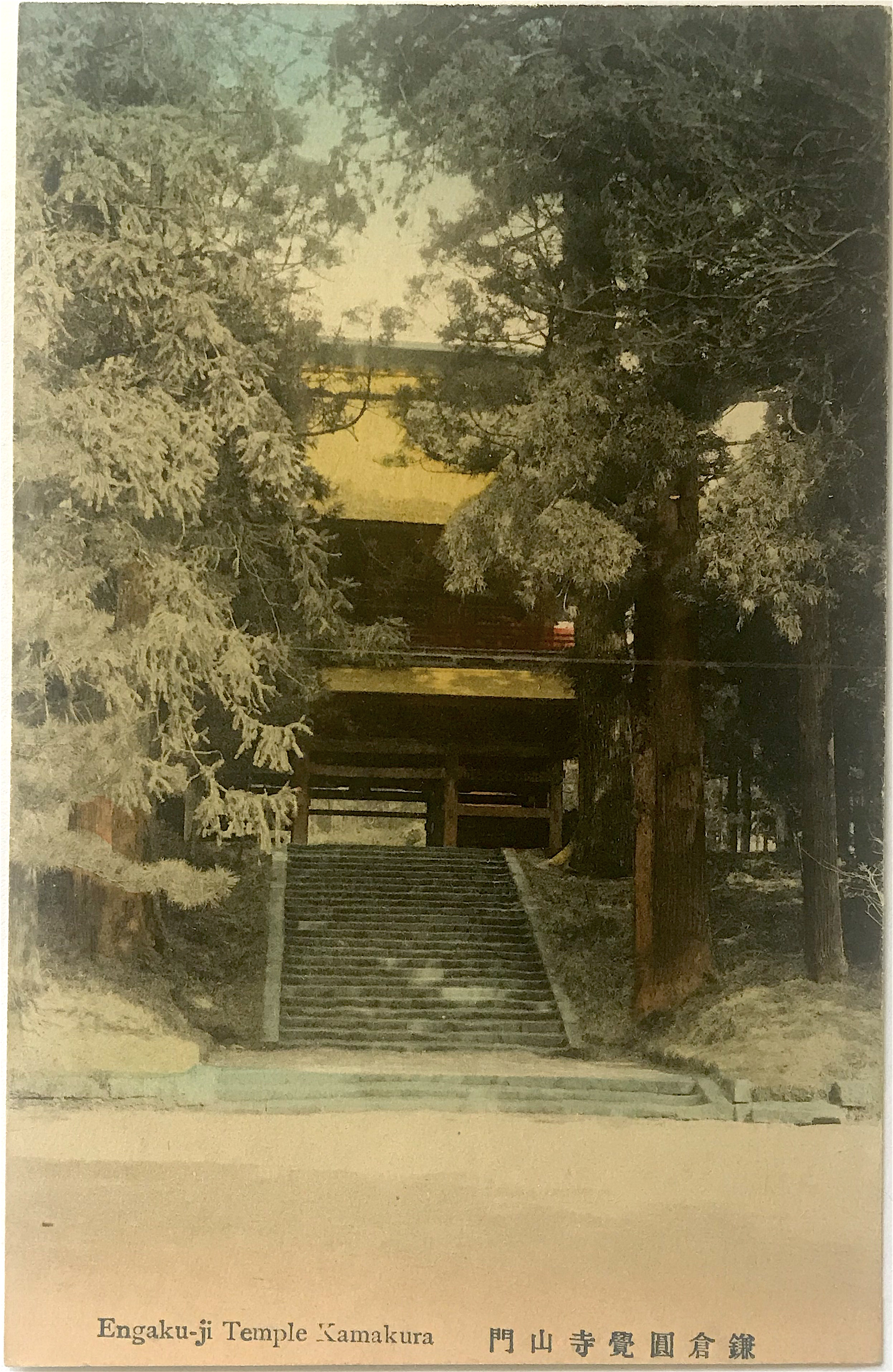

Figure 1

- Title/Caption: The Shinkoji Temple, Hyogo-Kobe

- Year: 1920’s

- Publisher: Sakaeya & Co.

- Medium: silver gelatin print on cardstock

- Dimensions: 5.5 in X 3.3 in

- Reverse Imprint: Postcard/郵便はかき

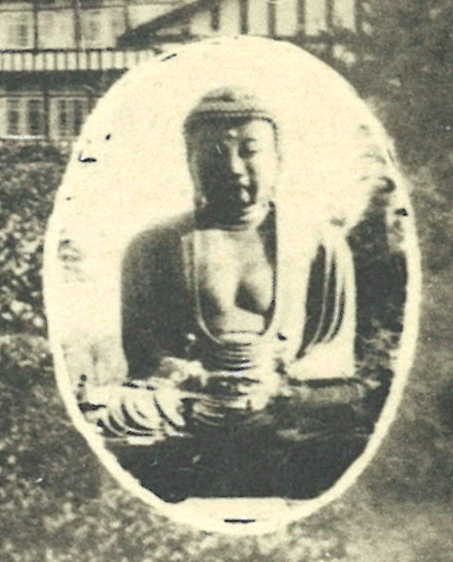

The postcard here depicts the Shinkōji statue atop its pedestal in the middle of the lotus pond [Fig. 1]. To the left of the statue is a large gable roof structure which acted as the main gate giving access to the inner monastic compound. Behind the plastered wall we see the tiled roofs of the bell tower and main hall. The small pond in front was used to rescue and release turtles.

The English caption clearly denotes the location of the image, but the Japanese caption provides more commentary on the religious relevance of the site. It notes that this temple as sacred location where Ippen passed away, a story that would resonate more with Japanese pilgrims than Western tourists. This also tacitly acknowledges the diverse reasons for visiting temples, as more foreign visitors were interested in seeing – and capturing – the picturesque sites of Japan. Like curio collectors they could return home with their souvenir spoils.

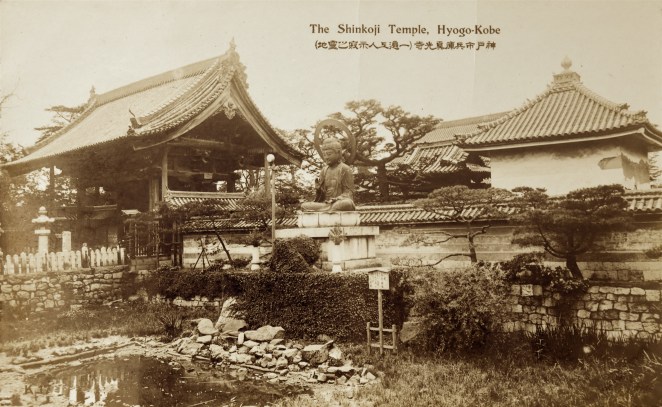

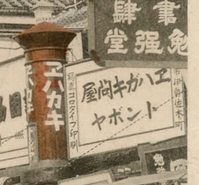

Figure 2 (detail of Figure 1)

The large halo fixed to the statue’s upper back, suggesting a radiant glow emanating from the icon, helps draw attention to the calm features of the buddha’s face [Fig. 2]. Without a person in the picture for scale it is difficult to assess that the statue is much larger than life-size; a person standing atop the ivy covered base would barely surpass the height of the square white stone pedestal.[2] The pole to the left of the pedestal appears to support a small round light that is level with the statue’s head. Viewed from the harbor, the city of Kobe and surrounding hillsides were known to cast a delightful glow at night, suggesting electric lights were installed throughout the region. When turned on, this light likely would have cast a gentle glow on the buddha’s face at night.[3]

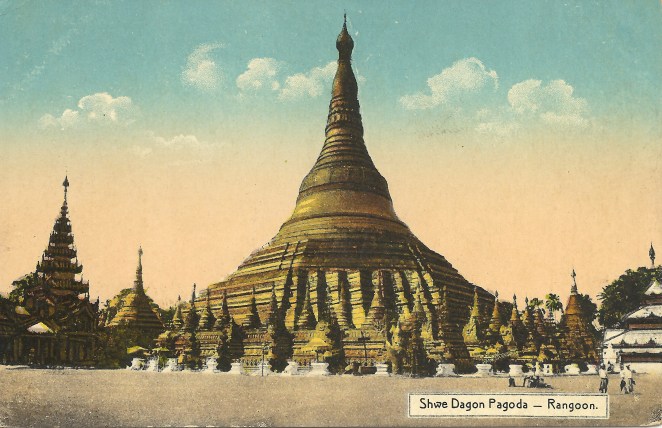

Figure 3

Figure 4

Unlike many Japanese produced postcards of the time, this is not a photomechanical print made with ink, but a silver gelatin photograph. Thus, this “real photo” postcard was chemically processed as a photograph on cardstock bearing a postcard design. By the early 1920’s several Japanese publishers were issuing real photo postcards as part of their commercial catalogues. Sakaeya & Co., the publisher of this postcard, was based in Kobe and many of its cards depict the environs of the bustling port city. The lion insignia in the stamp box was the trademark of Sakaeya, which was one of the largest distributors of postcards in Japan [Figs. 3 & 4]. Based on similar cards issued by other publishers, this card likely dates to the early 1920’s.

During World War II, the entire Hyōgo ward of Kōbe was destroyed by the allied firebomb attacks in March 1945. Most of “Old” Shinkōji was destroyed and the statue at the front gate appears to have been lost.[4] Temple records reveal the statue was installed on temple grounds in 1760. Nineteenth century Japanese photography studio prints and twentieth century picture postcards remain some of the best artifacts cataloguing this wonderful piece of Japanese Buddhist art.

Notes

*This is part of a series of posts devoted to exploring the development of a visual literacy for Buddhist imagery in America. All items (except otherwise noted) are part of my personal collection of Buddhist-themed ephemera. I have also published my working notes on identifying publishers of Meiji and early Taishō postcards and establishing a sequential chronology for Kamakura Daibutsu photographs.

[1] This statement mirrors the comments of globetrotter Edmond Cotteau, who visited Kōbe in late 1881 and published Un touriste dans l’Extrême-Orient: Japon, Chine, Indo-Chine et Tonkin in 1884, see p. 208.

[2] The height of the Shinkō-ji statue is noted as being 4.8 meters tall. This height is equivalent to the traditional measurement of “one jō and six shaku” (一丈六尺 ichijō rokushaku, often shortened to jōroku 丈六), which was considered to be the true height of the historical Buddha while standing. Many “Great Buddha” images in Japan were made to match this height. Since the Shinkōji image was made sitting, it would be close to twice the traditional height of the Buddha.

[3] The pole does not appear in studio photographs from the nineteenth century, nor in postcards issued before 1918. Another postcard in the Archive clearly shows wires leading from the pole to behind the statue towards the wall (it is missing a light bulb, however). It also shows towering wooden power lines in the background, proving the temple had electricity by at least the early 1920’s. See a cropped image of this postcards here:

[4] The temple website does not currently count the statue as among its current holdings. It is worth noting that a statue of the Buddhist figure Jizō was enshrined in 1936 and still remains on the temple grounds, thus some objects did survive the bombing. I have not found any resource to confirm the statue was destroyed, but it does not appear to be on display at this point. As for now, I must leave the question regarding the statue’s current existence as unknown.

References

- Fujimoto Kōzaburō 藤本弘三郎, ed. 1933. Nihon shaji taikan: jiin-hen 日本社寺大観寺院編. Kyoto: Hinode Shinbunsha. [here]

- Kaufman, Laura. 1992. “Nature, Courtly Imagery, and Sacred Meaning in the Ippen Hijiri-e,” in Flowing Traces: Buddhism in the Literary and Visual Arts of Japan, eds. James H. Sanford, William R. LaFleur and Masatoshi Nagatomi, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 47-75.

- Yanagi Sōetsu, and Waddell, Norman. 1973. “Ippen Shōnin,” The Eastern Buddhist, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 33-57.

Additional Posts in Visual Literacy of Buddhism Series

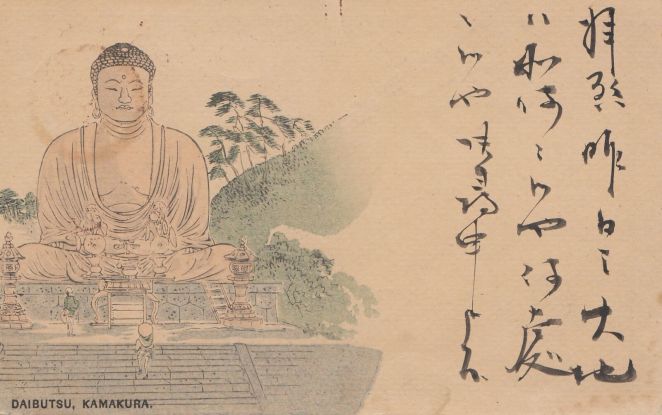

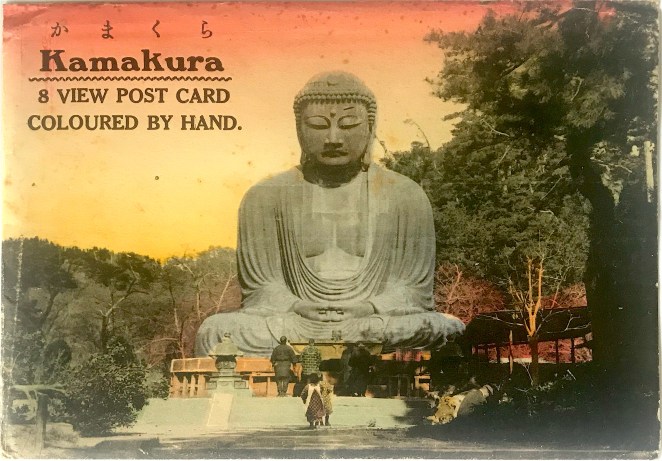

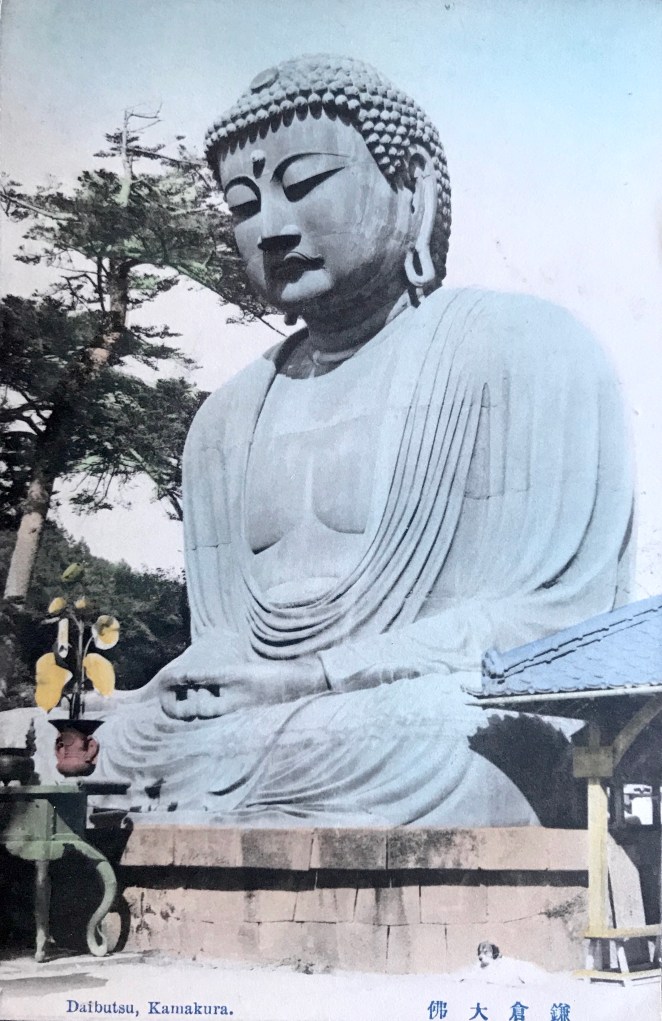

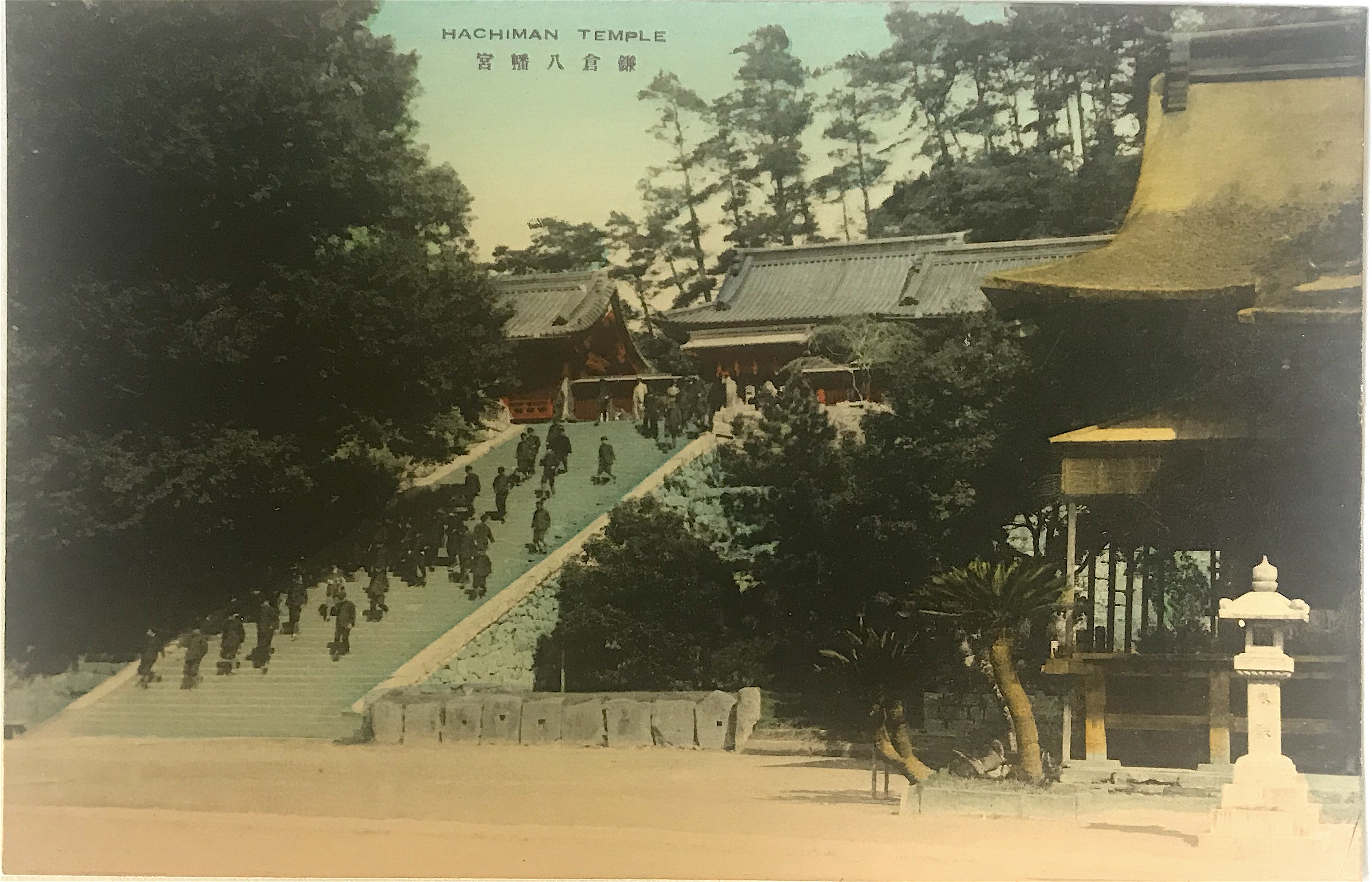

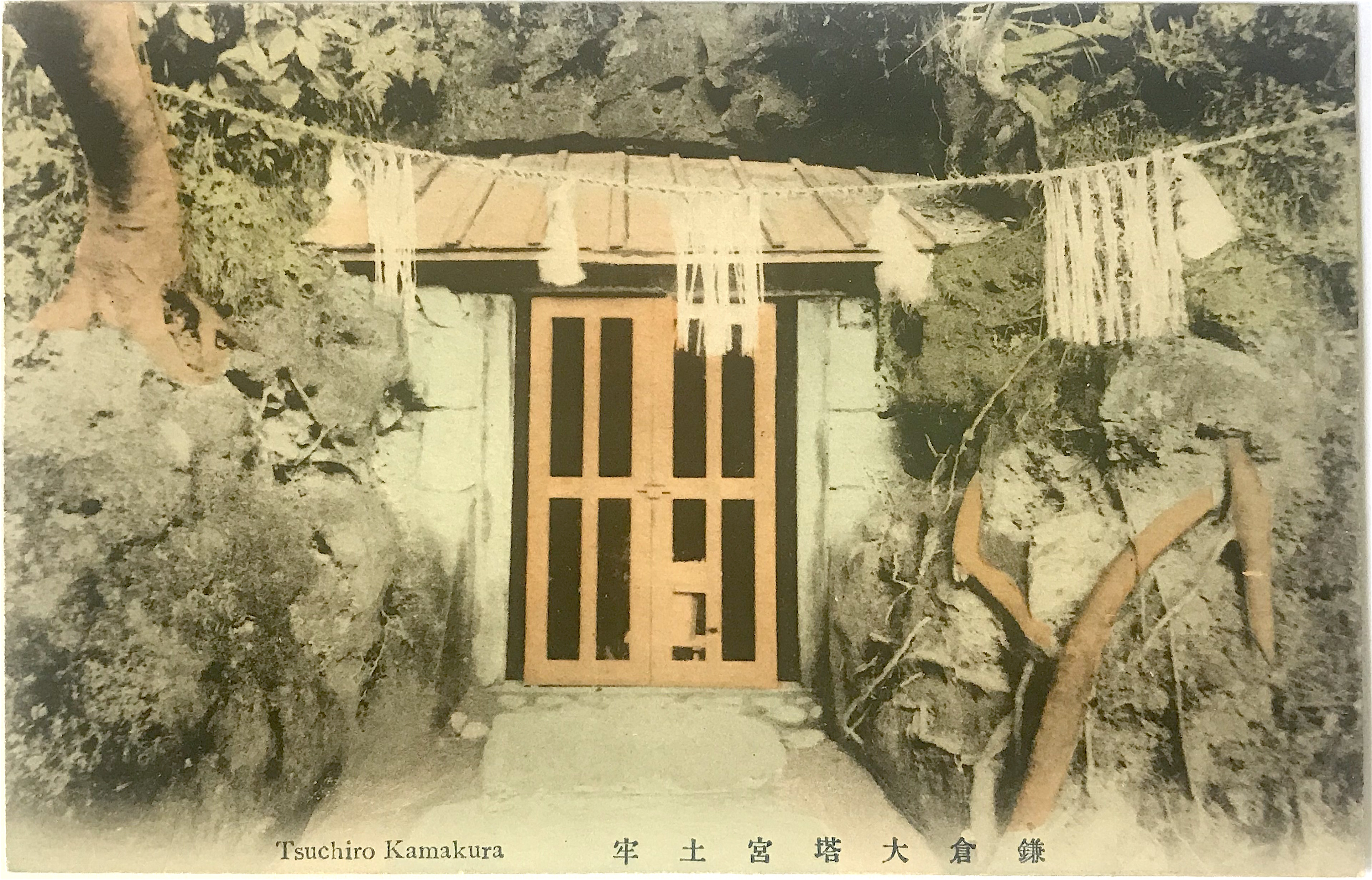

Sometime in the 1920s sets of picture postcards were more frequently issued in a paper sleeve or cover. These sleeves were initially imprinted with text or simple designs, but due to the highly competitive commercial market these utilitarian items became subject to the same visual expectations as the postcards themselves. The examples before us bear a hand-colored photographic image, which is given the same artistic care as the cards they hold [Fig. 1 & Fig. 2]. In addition to the minor and idiosyncratic coloring differences, each set uses a slightly different letterpress design. Set 2 also appears to be influenced by an Art Deco font style.

Sometime in the 1920s sets of picture postcards were more frequently issued in a paper sleeve or cover. These sleeves were initially imprinted with text or simple designs, but due to the highly competitive commercial market these utilitarian items became subject to the same visual expectations as the postcards themselves. The examples before us bear a hand-colored photographic image, which is given the same artistic care as the cards they hold [Fig. 1 & Fig. 2]. In addition to the minor and idiosyncratic coloring differences, each set uses a slightly different letterpress design. Set 2 also appears to be influenced by an Art Deco font style.

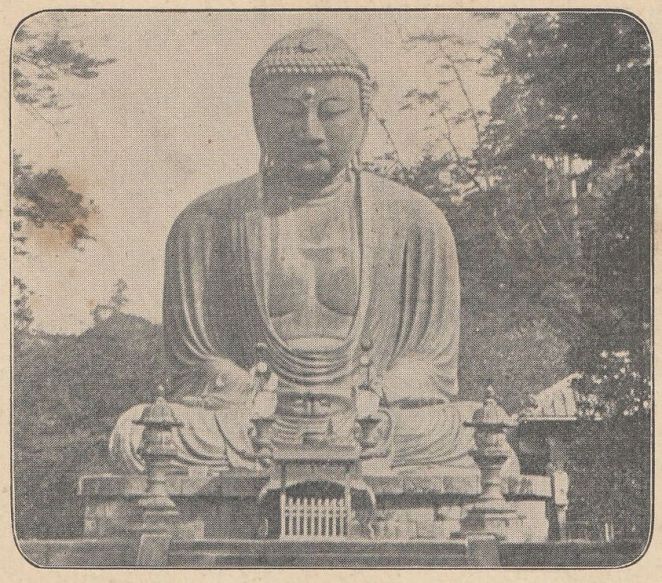

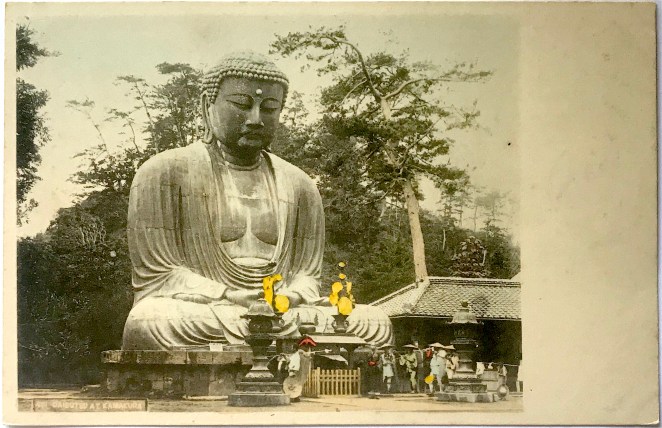

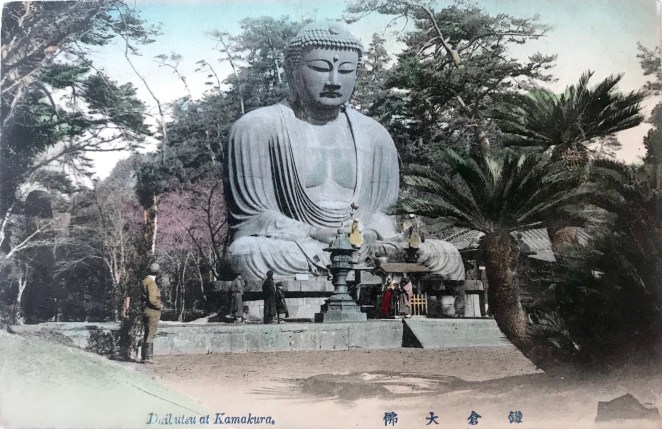

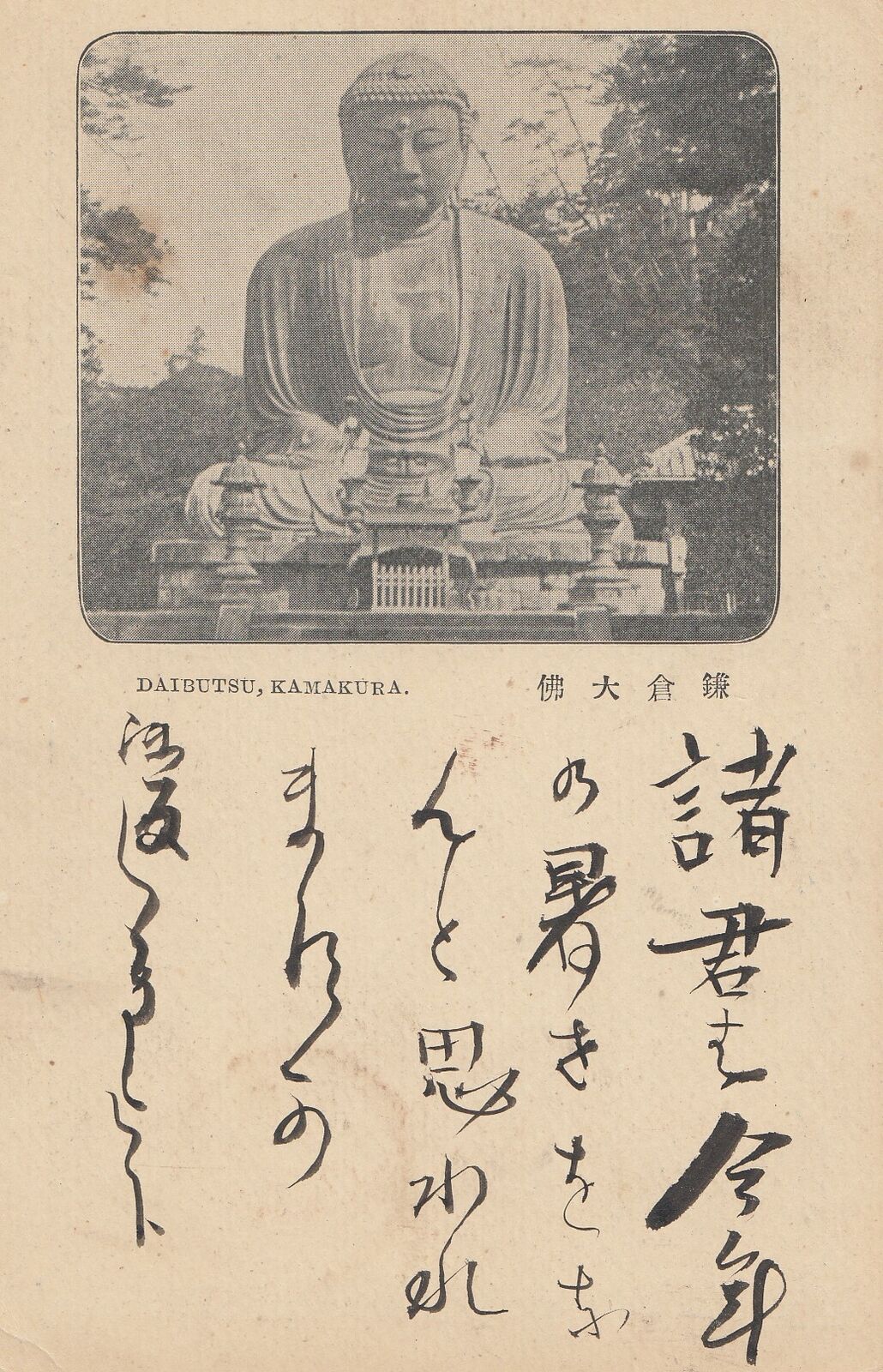

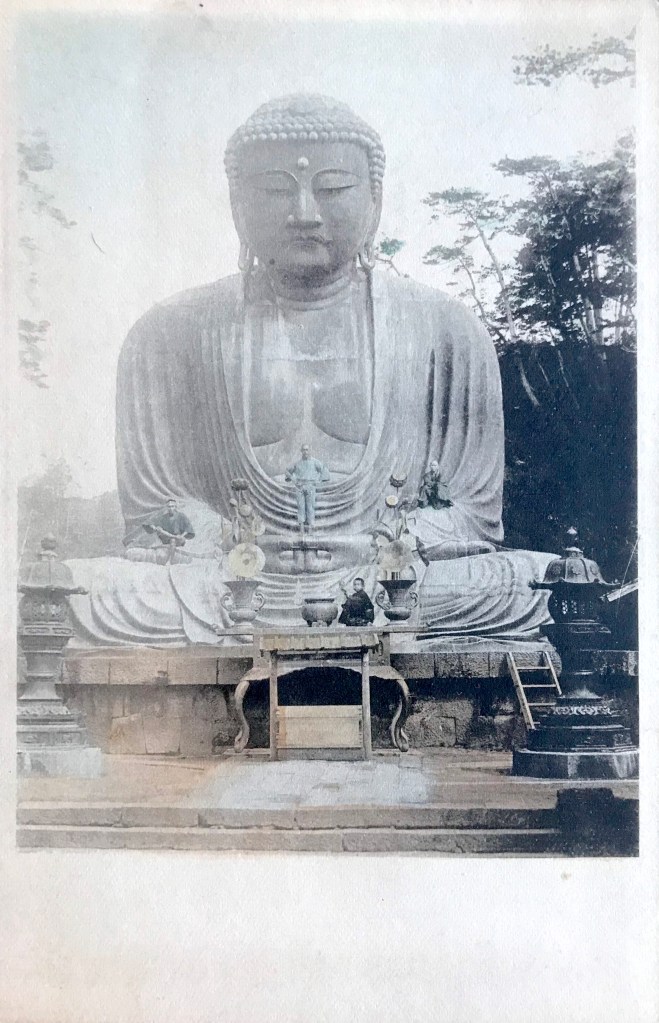

The photograph of the Daibutsu by Esaki (or one of his studio assistants) depicts the bronze statue from the southwest corner, an uncommon, but

The photograph of the Daibutsu by Esaki (or one of his studio assistants) depicts the bronze statue from the southwest corner, an uncommon, but

A variant style for “Carte Postale” can also be found. Note the stamp box is vertical.

A variant style for “Carte Postale” can also be found. Note the stamp box is vertical.

Akanishi (Kobe 神戸)

Akanishi (Kobe 神戸) Asahidō (Kyoto 京都)

Asahidō (Kyoto 京都) Benrido 便利堂 (Kyoto 京都)[no trademark, but uses distinctive font –

Benrido 便利堂 (Kyoto 京都)[no trademark, but uses distinctive font –  Hōeidō 保永堂 (Kamakura 鎌倉?)

Hōeidō 保永堂 (Kamakura 鎌倉?) Naniwaya Co. 浪華屋 (Kanda, Tokyo

Naniwaya Co. 浪華屋 (Kanda, Tokyo  Nisshinsha (Tokyo

Nisshinsha (Tokyo  S.N. Banshiudo

S.N. Banshiudo  Taisho Hato Brand 大正鳩ブランド (Wakayama

Taisho Hato Brand 大正鳩ブランド (Wakayama  Tōdai-ji 東大寺 (Nara 奈良)

Tōdai-ji 東大寺 (Nara 奈良)